Steel-eyed, sober, often grim and frequently dangerous, Ed Harris has carved a niche for himself portraying characters who can be flawed or misdirected.

Whether he’s playing an earnest astronaut (John Glenn in The Right Stuff) or a scarred gangster (A History of Violence), his parts are rarely less than formidable.

It’s no surprise that Harris is drawn to Westerns. He’s narrated documentaries on Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch and on director Budd Boetticher. What is surprising is that prior to Appaloosa, out in theaters October 3, he’s only acted in one, a made-for-TV Zane Grey oater Riders of the Purple Sage, which co-starred his wife Amy Madigan, and for which he received a Screen Actors Guild acting nomination. In fact, Harris has been nominated for Oscars four times, and he has taken home one Golden Globe out of a possible five.

Appaloosa is Harris’s baby. He found the book, secured permission from novelist Robert B. Parker to make the film, cowrote the screenplay and directed the film. His only other director’s credit came from his biographical portrait of abstract impressionist painter Jackson Pollock a.k.a. “Jack the Dripper,” who died in 1956. “It’s true, Pollock had a bit of the cowboy in him,” says Harris, “at least in terms of his self image.” And for an artist, or a cowpoke, image is everything.

The character Harris plays in Appaloosa is anything but your average saddle tramp. Virgil Cole is a town tamer, a man hired to chase out undesirables or fix unfixable messes, usually by any means necessary.

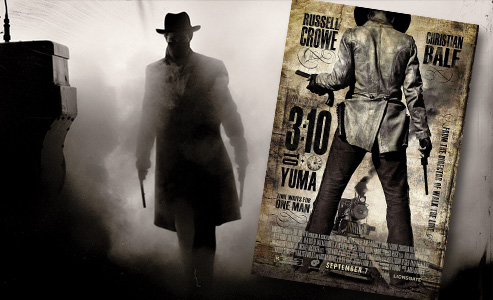

Like Oates, the amoral mercenary Harris played in 1983’s Under Fire, Cole is also a hired killer, but Cole has a code and a cause. He believes in the law. With his best friend Everett Hitch (Viggo Mortensen) in tow, he stands for a special kind of rough justice in a mythical West—the same West found in the stories written by Elmore Leonard. The movie was even shot on the same New Mexico set as the recent remake of Leonard’s 3:10 To Yuma.

Ed Harris: We used the same town as 3:10, but we totally redid it. You’d never know from that film where you were—everything was all close ups; you never got a sense of the country really or where they were. One of the things that I like about Appaloosa is, even though it’s an hour and 47 minutes, it takes its time when it needs to and you get a real sense of where you are, the town and the people in it….

It’s early 1880s, in the Southwest, and it’s definitely post-Civil War. I think Parker refers to some of the weapons that these guys were using that were at least after 1873, the Winchester ’73. In terms of the Indian situation, most of the Apaches were on the San Carlos Reservation by 1882, so you figure [the timing is] around there. At least in my mind. I don’t guess he ever does mention the date in the novel.

I think that Parker’s book definitely leans toward a more kind of classic-oriented story in the sense that it is a bit timeless and what’s going on with these people. It happens to be in the West; it happens to be around 1880. But in terms of the human drama of it all, it could be any time really. It’s about love, relationships, loyalty, greed, friendships, all that stuff.

TW:

There’s something about Cole and Hitch that reminds me a little of Call and McCrae from Lonesome Dove.

There are some similarities in their partnership and their friendship—the way they trust in each other.

In this case, Cole is the stoic and something of a hardass.

He’s kind of the head guy of the outfit. They’ve been riding together for a least a dozen years or so. Yeah, he gets a little brutal every once in a while, gets a little carried away. He’s got a temper.

There’s the scene where he pistol whips the guy on horseback.

Yeah, but the guy was bein’ a smart ass [laughs].

A great many Westerns are about friendships of one sort or another, between men like Hitch and Cole.

Like Ride the High Country, and even the friendship between [James] Stewart and John Wayne in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance. I mean, it’s a different kind of a friendship, but the relationship between those two guys is really the heart of the story. Butch Cassidy, even Gunfight at the O.K. Corral, in terms of Earp and Doc Holliday—it’s about guys looking out for, watchin’ each other’s backs, and knowin’ you’ve got somebody who’s on your side, you know?

In Appaloosa, you really get the feeling that Cole’s been at it a little bit longer and has a little more experience. He’s kind of the boss of the outfit, even though they’re pretty much 50-50 in terms of making decisions and everything….

Hitch tells the story in the book, and, really, the film’s told from his point of view as well. Hitch wasn’t sure what he wanted to do with his life; Cole kind of said, “Partner up with me,” and gave him something to do for a good chunk of time. You get the idea that his relationship with Cole has defined him for the last dozen years or so.

Hitch is the kind of friend who fixes messes whether his friend likes it or not, or even comprehends it.

Virgil’s always talking about the law and how you’ve gotta stick with that. He identifies himself as a lawman, and if he breaks his own law, then he ain’t gonna be a lawman no more. So Hitch basically says, “Well, if Virgil finds out what just happened, he ain’t gonna be a lawman anymore cause he’s gonna blow this guy away, so I guess I better do it”—that’s kind of the reasoning that’s at work here. He not only gives the guy a chance with Allie [Renee Zellweger], but he protects his buddy from losin’ his livelihood.

In Parker’s book, I liked how mercenary Allie is, always attaching herself to the closest alpha male. Did that survive from the novel to the film?

Oh yeah—you don’t know a damn thing about this woman except that she’s just arrived on the train from somewhere and she says her husband died…. She’s got some decent clothes and speaks well and plays the piano a little bit, although not very well, and [laughs] she does what she has to do! Renee’s character is a pretty tough character, cause she’s not the most sympathetic girl in the world. I thoroughly enjoyed working with Renee, and I really appreciate the work she did.

There’s a risque scene in the book—

Well, there’s the one scene where she’s been captured, and Hitch and I come upon her, and we do see her naked down in the river down there. But it’s a long lens—we’re looking through a telescope [laughs]. You don’t see Renee naked all that much, but you do get the idea what’s going on with her. She’s got a great body on her, actually.

Jeremy Irons is bad guy Randall Bragg.

He did a great job. I really wanted Bragg to be a counterpoint to Virgil in terms of his sophistication and all.

You worked with Viggo pretty recently in 2005’s A History of Violence.

Viggo, I can’t say enough about. I showed him this book, and I asked, “If I get a good script of this, will you do this with me?” And he said, “Yeah.” …And even though he was incredibly busy, up to a couple days before filming, the guy is a man of his word—which is a rare thing these days. He was there, was ready to go and did a great job. We worked together really well. I take my hat off to him.

What are your connections to Westerns?

I was born in 1950, right? So I grew up watching all the Westerns on TV. When I was a kid, my brother was Gene Autry and I was Roy Rogers. I’ve always been a fan of the Western genre. Some of the classic Ford movies are so great, and Peckinpah and Anthony Mann and all those guys….

I started riding back in the early 1980s when I was doing the Sam Shepard play Fool For Love, where the guy is a broken down rodeo guy. I got into ridin’ Western, and I just really liked it. We had a place out in New Mexico for a little while that we ended up getting rid of, but I go up to Montana every summer and ride around. I just like it. I like the quiet, I like the country, like horses. Gotta have a good hat.

We both grew up watching TV Westerns.

There were some good ones. Have Gun Will Travel, especially. They were runnin’ Gunsmoke on the Westerns channel, couple years ago, every night at like seven. We would watch that every night, my family—have dinner, watch an episode of Gunsmoke. Man, I just dug it. It was fun man. They had great actors on the show, you know?

Tommy Lee Jones told us a great story about a Hopalong Cassidy sweater his father once bought him, and how proud he was of it.

One Halloween, when I was in kindergarten, my mom made me up like a hobo. I had a rubber cigar and little whiskers and dotted makeup on my face, a stick with a red bandanna with stuff in it, you know, pants with patches on it. I went to school, and before I even got in the door, some girl laughed at me. I sat down on the stoop and refused to go in. They called my mother. I went home, dressed up as a cowboy, came back and it was just fine.

Robert B. Parker

Robert B. Parker is no stranger to Westerns. Even though he’s best known as the creator of Boston detective Spenser, the somewhat damaged Massachusetts police chief Jesse Stone and P.I. Sunny Randall, a character he created for actress Helen Hunt, Parker has been a Westerns fan his entire life. He is the author of Gunman’s Rhapsody (2001), a story of a pre-Tombstone Wyatt Earp that also features Doc Holliday and a virtual who’s who of Western icons. He also contributed to the screenplay of the remade Monte Walsh, which starred Tom Selleck as Shane author Jack Schaefer’s amiable ranch hand.

Even though Parker has had a hand in a truly remarkable number of TV productions based on his characters and stories, it’s surprising to find that AppaloosaResolution and the forthcoming Brimstone, nothing would please him more than to see Ed Harris’s film make a “zillion” dollars and launch a new franchise. is the first feature film to be made from one of his books. Since Parker has written two sequels to the original novel, the recently published

True West spoke to Parker from his home in Massachusetts.

Robert B. Parker: They did a great job on the movie. I’m thrilled with it.

TW: Why?

Because they got my book, the issues in the book. At one point, someone says to Virgil Cole, “You just kill people.” He says, “No, I don’t. I enforce the law.” Well, that’s the issue. And when Virgil gets to a point where he needs to kill people for reasons other than the law, he gets a little lost, and that’s the next novel. He retraces the resolution of that issue from Appaloosa.

The film … is filled with grandeur, but it isn’t about the grandeur. There is no wasted talk. Allie comes off sympathetic in the movie, and you sort of understand her—not by what’s said, but how Renee looks when she’s being Allie. As I say, it’s everything that the thing should be.

In your novel, I like Allie the most; she’s so unabashedly intent on self preservation.

Find an alpha male and whichever one is the top one, that’s for her. Renee got that, and she got it in a couple of scenes, without saying a word. You could tell that it killed Allie, that she really wished she wasn’t like that, but she was.

One of the things about writing a Western is you are denied all the handy Freudian business that’s available to you when you’re writing a novel in the 21st century. That may be one of the reasons Renee’s so good, I don’t know. But it was a delight to see her understand that character as well as I did.

Appaloosa is a kind of mytho-Western, like Elmore Leonard’s stories.

I’m under no illusion that this is really how the West was. This is the myth of the West, like the Arthurian romance. I have no confusion about that, and I’m pretty sure Dutch [Leonard] doesn’t either.

Leonard admits that most of what he knew about the West he learned, in Detroit, from Arizona Highways magazines.

He’s told me that too. I have spent my life living in Boston. But I did travel out there; I did go to Tombstone two or three times, spent time in Arizona, driven across the country five times, transporting my dog back and forth, cause we don’t fly her in any old plane. Anyway, I got a sense of the West, and Tombstone—despite the fact that you can buy Wyatt Earp burgers and stuff—is still there; you can see the old town there. I found that interesting.

But most of what Leonard and I learned about the West came from watching Westerns or reading Arizona Highways.

Did you read a lot of Westerns when you were young?

I grew up reading adventure stories about the Kentucky frontier and stories by Joseph Altsheler, but the movies are what brought me to the West. I’ve read very few Western novels: The Way West, The Big Sky. Basically, it was the movies, as far back as I can remember. When I was a little kid, I was watching Gene Autry. I’m not sure that’s the authentic West either [laughs].

Cowhands actually did croon and yodel beneath the stars.

Yeah [laughs]. I started going to the movies around 1938, and I liked Westerns from the beginning. Bad ones and the good ones, and it doesn’t get much worse than the worst of the Gene Autry pictures.

I look at these films now and then on the Westerns channel, and I’m astonished at how terrible some of them are! [Laughs.] Guns and horses and jeeps and radios, and there’s always that idiot [sidekick] Smiley Burnette.

But where would we be without Walter Brennan and those guys?

We’d be fine. Of course, Brennan could actually act …my mother and he were the same age, and [they] were once photographed together in a pony cart.

Your mother and Walter Brennan in a pony cart?

Yeah, when they were both babies. I think he grew up in Swampscott or Salem [Swampscott, 1894]….

How did they know each other?

I don’t know. I mean, everybody’s dead [laughs]. I saw the picture, and they said, “That’s Walter Brennan!” I was destined for Westerns, cause my mother was a baby with Walter Brennan!

I probably have been drawn more to the Westerns of late because it represents so much freedom for a writer …you’ve got so many more limitations to constructing a story in a contemporary society. I’m sure you’ve read Robert Warshow’s essay [“Movie Chronicle: The Westerner”]—it’s a great one, the best one I know, about Western movies. He talks about the movements of men and horses and space. It’s rather difficult to describe what it means to do it, but compared to Spenser working in the mean streets of Boston, let’s say, to letting Everett Hitch and Virgil Cole loose out in the West somewhere … it’s a refreshing change.

Tell us about the Western movies that influenced you.

The first Western that really grabbed me was Shane, which is one of those rare instances when it was a better movie than a book.

You were an adult when that .film came out.

1953. I would have been 21…. I’m old enough to have watched the serials, Ken Maynard and his great horse Tarzan, all that good stuff. But the first great Western movie that I saw was Shane. Red River was another. One of my all-time favorite movies is one that few people know, it’s called Ulzana’s Raid. I think that is a great movie.

I like the John Ford stuff. I wish there was a little less of the cute Irish singers, and I could do with a smidgen less of Victor McLaglen. But [Ford] had a great vision. The Searchers was pretty good, and all of the John Wayne cavalry trilogy I enjoyed greatly.

I like Peckinpah—did you ever see the TV series he directed early in his career with Brian Keith [The Westerner]? They’re as good as it gets in series television, I think. Brian Keith was amazingly good.

Your books, like Leonard’s, exist in the Western of mind and myth.

My publisher had some trouble with the places—he asked, “Well, what state is it in?” And I said, “It isn’t in a state; it’s just somewhere in the West.” I was quite careful not to ever mention in Appaloosa where it was, because I wanted that kind of timeless Western myth place…. I was trying to write about, when the fact and the legend collide, report the legend—however that goes, from Liberty Valance.

Every culture has its legends, and ours is the West. England has the Arthurian romance, Robin Hood, the countryside romance as opposed to the reality of urban life. Most of them do. This is ours. It resonates.

You’ve been lucky with the casting of your characters—Tom Selleck, Robert Urich. And you couldn’t do better than Ed Harris and Viggo Mortensen.

Joannie [Parker’s wife] and I had dinner with Harris when he was here shooting Gone Baby Gone…. He told me what he was gonna do and I said, “Okay. Why don’t you go and do it?” He said, “We can’t give you much up front,” and I said, “Alright. You can give me some later,” which they did. And I trusted him. The first time since 1982, in 26 years, that I actually met someone that I had every confidence in and I still do. I’d love to work with him again.

I wonder if, at this point in your career, if having a really good film come out of something you wrote, might not mean as much as making a zillion dollars.

[Dead silence.]

I could be wrong…

[Laughing loudly] Yes, you could! I’d like it to be both, but if I could choose one, give me the zillion!

Maybe you should take a shot at writing a superhero story.

[Laughs] I don’t think I can.

Batman of the West?

Yes, yes. The dark knight astride his stallion.