Normally a stagecoach was pulled by what was known as a 6-up hitch. Less common was a 4-up or four horses. The wheel team on a 6-up, those at the rear of the team, were the largest, strongest of the six. A complimentary nickname for a large, powerful man was ‘wheel horse.’ The wheelers started the coach moving. The swing team, the middle team, were smaller than the wheelers, but likewise well-trained. The lead team, also smaller than the wheelers, were the least well-trained of the hitch. They could look thru a collar & they reined fairly well, but otherwise they could be a mite flighty. The better-trained & larger wheelers & the better-trained swing horses held them in check.

During the 1850s the “Jackass Mail.” was a stage line from San Antonio to San Diego that used mules exclusively. There was a stretch of sand dunes west of Yuma where the passengers had to ride mules.

There were actually three types of coaches–the regular Abbott & Downing Concord were the most common. Sometimes they actually had glass windows & usually had kerosene lamps on the outside. This was a very heavy coach & required at least a 6-up hitch.

Author Gerald Ahnert writes Butterfield chose Abbot-Downing for his stages because of their suspension technology was best suited to the low relative humidity of the southwest. Their wheels were the only ones that wouldn’t fall apart.

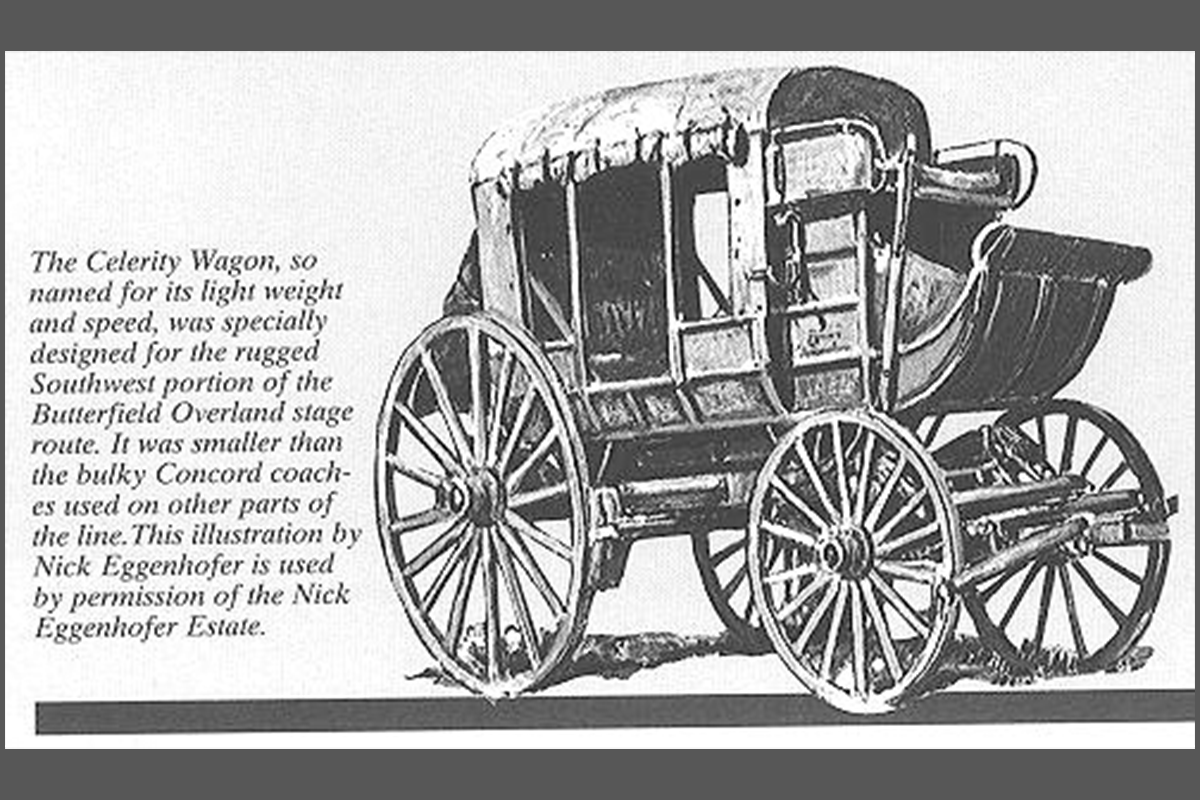

The Celerity was much lighter built & often had a canvas roof & wooden sides. It would have leather side curtains rather than glass windows. The seats broke down so one could sleep. You could successfully operate a Celerity with a 4-up hitch, but they were built for speed so most often they used 6-up hitches. There were a lot more Celerity’s in the arid Southwest than Concords.

The 3rd type was the lightweight and less expensive Mud Wagons. This was an extremely lightly built coach with canvas sides & roof. There’s an example of a mud wagon in the Witte Museum in San Antonio. I believe it once belonged to the King ranch. Mud wagons had extremely wide wheels & iron tires & were used primarily in bad weather, when the mail absolutely had to go thru. A stage line with a U.S. Mail contract was required to move the mail a minimum of 15 miles a day regardless of weather or other problems. Repeated failure to move the mail 15 miles a day would result in a loss of the contract. That mail contract was the reason most stage lines existed. Passengers were a secondary concern. Moving the mail was the be-all & end-all for the major stage lines–the reason they could continue to exist. Without a government mail contract, unless the line was a small one serving only a few local towns, a stage line simply couldn’t stay in business.