Adventure awaits the traveler on great cattle drive routes from Texas to Kansas.

Among Kansas cattle towns, 1871 is probably best remembered for Wild Bill Hickok’s gunfight with Phil Coe in Abilene. But there was another violent shootout that year that’s often overlooked, even though it was bloodier than the one in Abilene later that year.

The Chisholm Trail was entering its fifth year in ’71, when an estimated 600,000 longhorns would come north from Texas, but Abilene would have competition from Ellsworth and Newton. Joseph G. McCoy, who had made Abilene by building the Drovers Cottage and Great Western stockyards, oversaw construction of Newton’s stockyards.

Rollin’, rollin’, rollin’

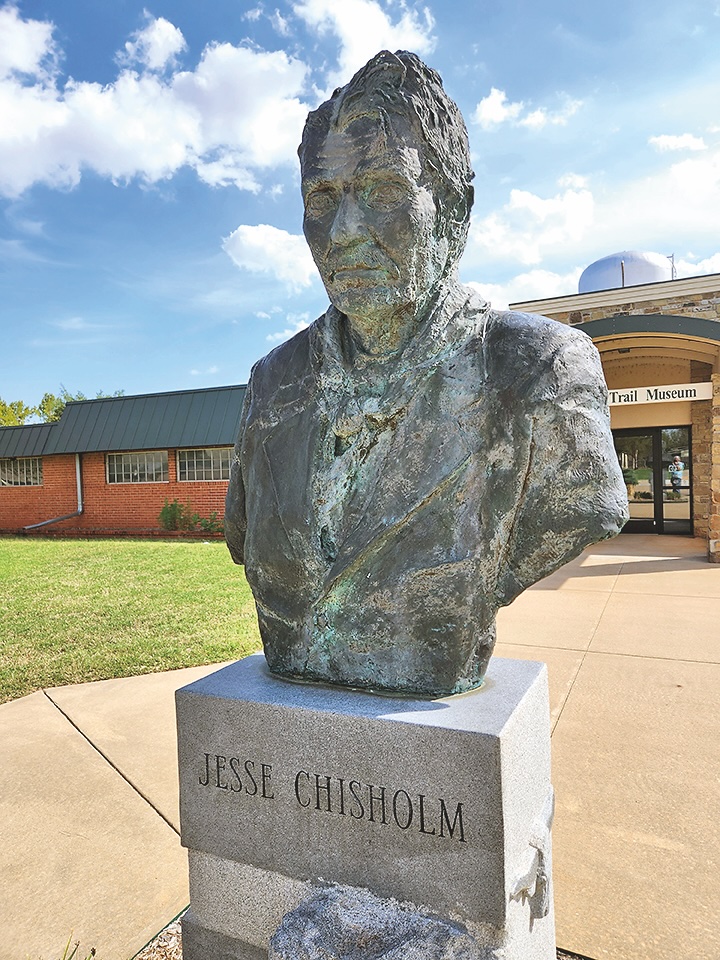

While trader Jesse Chisholm’s trail went from present-day Oklahoma and into southern Kansas, the cattlemen’s version of the trail began in southern Texas, moving to San Antonio (Briscoe Western Art Museum) and Waco (Helen Marie Taylor Museum of Waco History), where a suspension bridge, the longest single-span type west of the Mississippi, had opened in 1870.

From there, cowboys pushed herds through Fort Worth (Sid Richardson Museum), which was slowly growing. “New buildings are going up all over town,” the Fort Worth Democrat proclaimed, “improvements are being made in every direction, in spite of ‘hard times, hard times come again no more.’”

Herds crossed the Red River near Burlington (renamed Spanish Fort in 1879, when H.J. Justin—recognize that name, boot-wearers?—started making boots for cowboys). The trail continued through present-day Oklahoma, which preserves its cattle-drive legacy at Duncan’s Chisholm Trail Heritage Center and Kingfisher’s The Chisholm. Trail crews entered Kansas near the emerging cowtown of Caldwell (Border Queen Museum) and pushed through Wellington (Chisholm Trail Museum) and Wichita (Old Cowtown), which would take over Newton’s cattle market in 1872.

On to Newton

Newton was just up the road in Harvey County. With the arrival of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe in July—and with McCoy’s stockyards able to hold 4,000 longhorns—the town was ready. In fact, some herds had stopped before the first train arrived.

“Several thousand head of Texas cattle are now grazing in this vicinity…and thousands more are coming in every day,” Topeka’s Kansas Daily Commonwealth reported May 30. A small part of town south and west of the railroad tracks became known as Hide Park because “girls showed off so much hide.” While some newspapers in 1871 spelled it H-y-d-e, the story goes that Newton changed Hide to Hyde, Harvey County Historical Museum & Archives curator Kristine Schmucker tells me, to make it sound respectable.

It wasn’t.

The Kansas Daily Commonwealth said “good and even honorable men” could be found in Hide Park, but most “drink, swear and fight, and life with them is a round of boisterous gayety and indulgence in sensual pleasure. Of course where such characters prevail, abandoned women congregate, and Newton is liberally represented by the latter class.”

Law was haphazard—The Wichita Tribune reporting in August that “Rogues, gamblers, and lewd men and women run the town”—but policemen were hired for a special railroad bond election on August 11. Two men who signed up for that job, Mike McCluskie and a Texas gambler named Billy Bailey, got into an argument, which turned into a fistfight, and then a gunfight in which Bailey was mortally wounded. McCluskie fled town but returned after a week. On Saturday, August 19, he entered Perry Tuttle’s dance hall to gamble.

Filmmaker Walter Hill points out some key elements in his book/CD The Cowboy Iliad:

Back then, Newton was like Abilene,

Dodge or Wichita –

A railroad town and cattle town stuck

At the far end of the Chisholm Trail …

Most ways, these places were about the same.

Loose money.

Not much law and order.

Everybody wearing a gun.

Everybody drinking whiskey.

Massacre time

By 1 a.m., Tuttle was getting nervous. The band left, but many customers didn’t, even when Tuttle said he was closing. McCluskie kept playing faro. Cowboy Hugh Anderson, one of Bailey’s friends and the son of a prominent Texas rancher, came in at 2 a.m. “with murder in his eye, and foul mouth filled with oaths and epithets,” the Emporia News reported.

The gunfight began. McCluskie’s pistol misfired. Anderson’s didn’t, and the gambler fell with a bullet in his neck.

What happened next is mostly conjecture.

A second man, possibly a McCluskie friend commonly called Jim Riley, opened fire, shooting Jim Martin in the neck. Martin, who had been trying to calm everyone down, ran outside and died in front of a saloon. Anderson was severely wounded but would survive and escape prosecution when his father arrived and managed to sneak his son out of town. Five other men were shot—a brakeman and two Texans eventually dying from their wounds, and two others surviving.

“Newton has been designated as the wickedest place in Kansas,” the North Topeka Times reported on September 28, 1871, “and has received a name abroad which makes her famous as a wild town.” But the correspondent went on to say that “while we condemn we should also remember the few virtues it maintains…,” pointing out “that there are many good men there who have the best interests of the present and future prosperity of the town at heart, and are laboring for its advancement.”

A year later and no longer a cowtown, Newton had changed. The Newton Kansan reprinted an item from Ross’s Paper on August 22, 1872, that pointed out that “This young city, so lately famous for its Texas cattle trade and cattle men’s brawls” had transformed into “a thriving, orderly place, and really a most desirable locality, in the character of its people for sobriety, morality and enterprise….”

Gone but not forgotten

While Newton’s Harvey County Historical Museum documents what became known as “Newton’s General Massacre” and a few historical markers can be found in town, Newton doesn’t celebrate its cowtown history the way Abilene, Dodge City and others do. It hasn’t forgotten that history, but prefers being a quiet, friendly town.

Which The Kansas Daily Commonwealth had predicted shortly after the General Massacre:

“Newton, with all its faults and wickedness, will some day outgrow them and become one of the most important towns in southwestern Kansas.… We trust all those who may have occasion to visit this interesting locality may have as good luck in receiving courtesies and kindness as we did.”

Published by Kensington Books in July, Johnny D. Boggs’s Bloody Newton is a fictional account of the founding of Newton and the events leading up to and after the “General Massacre.”

A Wide Spot in the Road

OLD FORT PARKER

About 45 minutes east of Waco near Groesbeck, Texas, sits a reconstructed site of one of the legendary events in Texas history. Silas M. and James W. Parker built a log palisade fort in 1834 or 1835 for settlers’ protection, but on May 19, 1836, Comanches and Caddos attacked the fort, killing Silas and four others and abducting five captives, including 9-year-old Cynthia Ann Parker, who would become the mother of Comanche leader Quanah. In the 1930s, a replica of the fort was constructed, then rebuilt in 1967 and operated by the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Since 1992, the fort has been run by the City of Groesbeck and Fort Parker Historical Society. The fort, which includes a visitors center, is typically open 9 a.m.-5 p.m. Wednesday-Sunday. Admission is $5 for adults, $3 for children. The fort also holds special events, including Single Action Shooting Society competitions. oldfortparker.com

Good Eats & Sleeps

Good Grub: One Thirty-Five Prime, Waco, TX; Nic’s Grill, Oklahoma City, OK; Public, Wichita, KS; Mojo’s Coffee Bar, Newton, KS

Good Lodging: Crockett Hotel, San Antonio, TX; Stockyards Hotel, Fort Worth, TX; The Lindley House Garden Cottages, Duncan, OK; Delano Bed & Breakfast, Wichita, KS