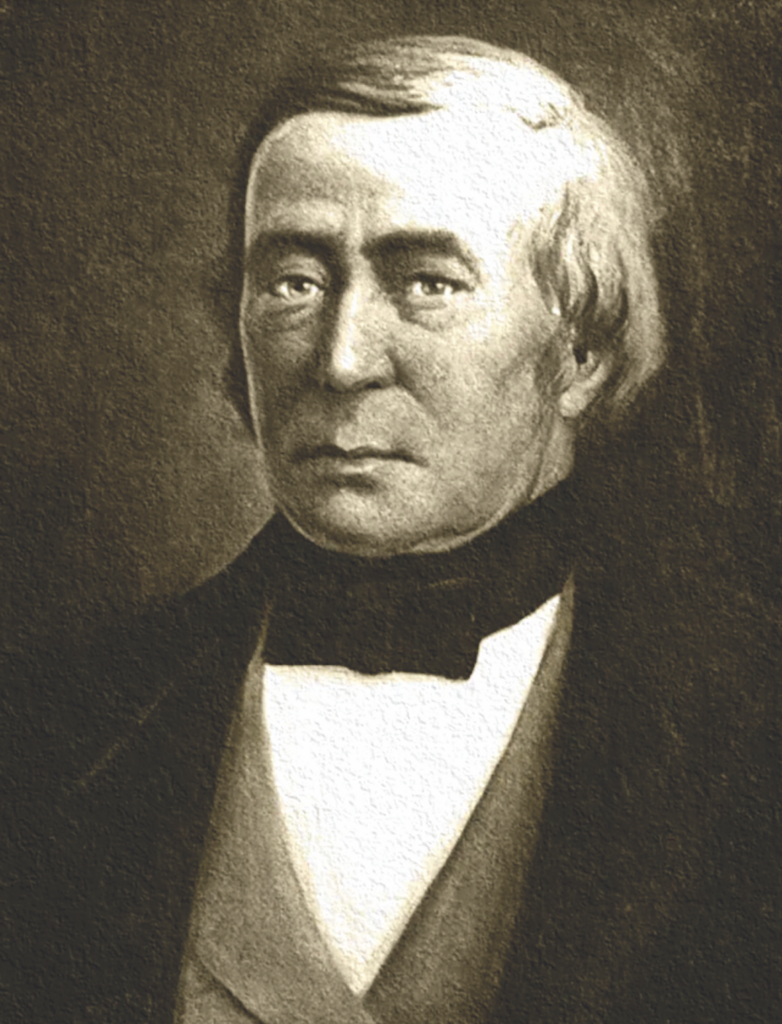

Jim Bridger, Thomas Fitzpatrick, William Sublette and dozens of their companions waded into cold mountain streams 200 years ago, setting beaver traps and establishing an industry. They were doing the job Gen. William Ashley and Maj. Andrew Henry advertised in 1822 in St. Louis when they posted notices for 100 young men to explore the headwaters of the Missouri River, launching the mountain fur trade with their Rocky Mountain Fur Company.

Ashley’s objective in entering the fur trade was to raise money for a political career. Henry became his partner to manage the operation; he had experience having worked for the Missouri Fur Company from 1809 to 1811. In that era, the fur operation involved trading parties who primarily relied on Indians to bring pelts to fixed posts and exchange them for goods that would make their lives better. Most of the trading took place at posts established along the Missouri River.

But in 1822, when William H. Ashley advertised for “One hundred men, to ascend the river Missouri to its source, there to be employed for one, two or three years,” he had already envisioned changing the way the industry worked.

His company would stake the men who answered the advertisement supplies like guns, powder, lead and traps. Those trappers would then overspread the Rocky Mountain West, setting their traps and working in the beaver streams of the region. They would repay the company with half of the furs they harvested. But the other half of what they caught were their own property. This gave the men incentive to work hard—for the company and for themselves.

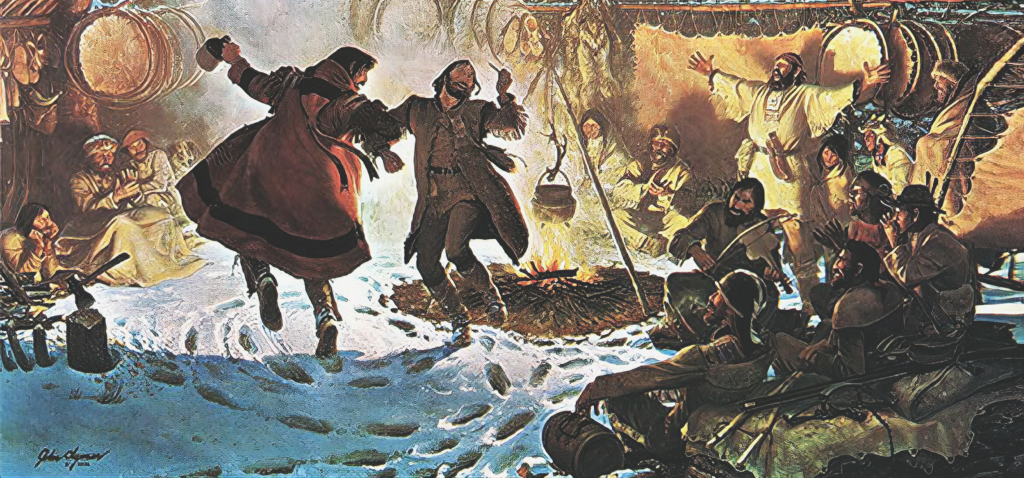

It wouldn’t be long before Ashley’s Hundred would gather at an innovating trading camp out west where they “tried to out-brag and out-lie each other in stories of their adventures,” even as they traded for supplies to continue their work.

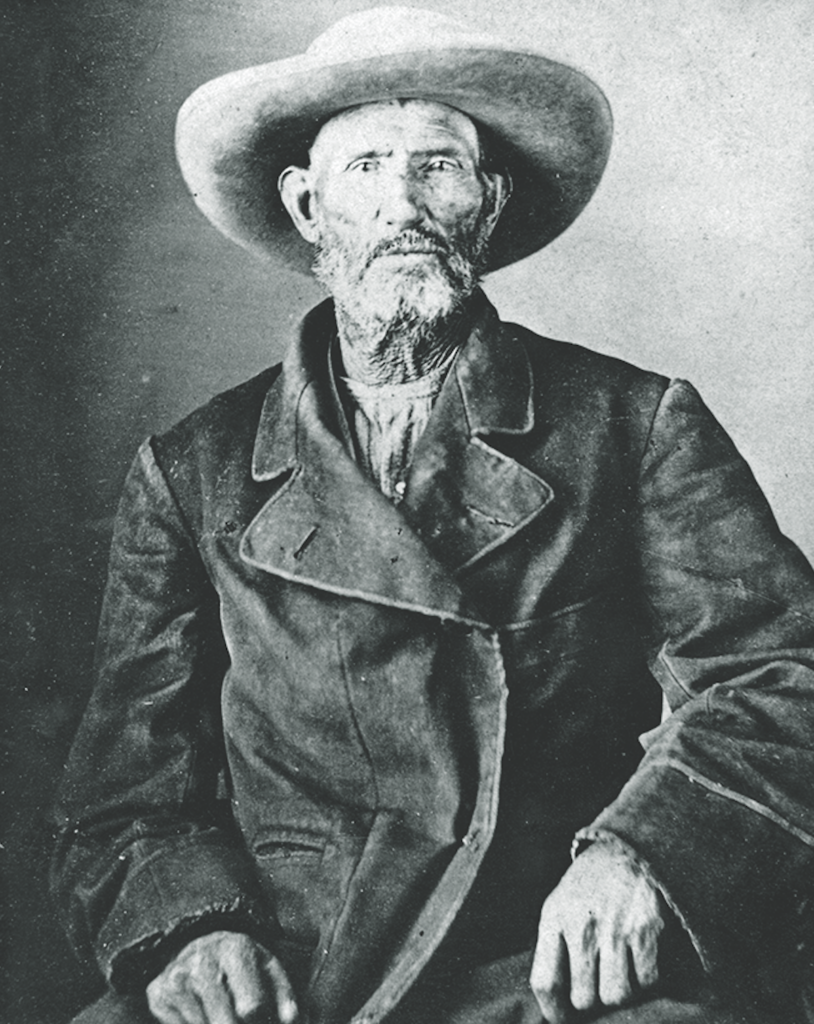

The men Ashley recruited—initially about 150 of them—became the first free trappers. Some were quite loyal to the company and would eventually even own it, but all were also independent, seeing their own best opportunities. They traveled extensively on foot and by horseback, learning and mapping the country and developing friendly connections with several of the Indian nations. Their names are iconic in Western history: Thomas Fitzpatrick, Jim Bridger, Hugh Glass, James Beckwourth, David Jackson and dozens more.

As Washington Irving wrote: “There is, perhaps, no class of men on the face of the earth…who lead a life of more continued exertion, peril, and excitement, and who are more enamored of their occupations, than the free trappers of the West. No toil, no danger, no privation can turn the trapper from his pursuit.”

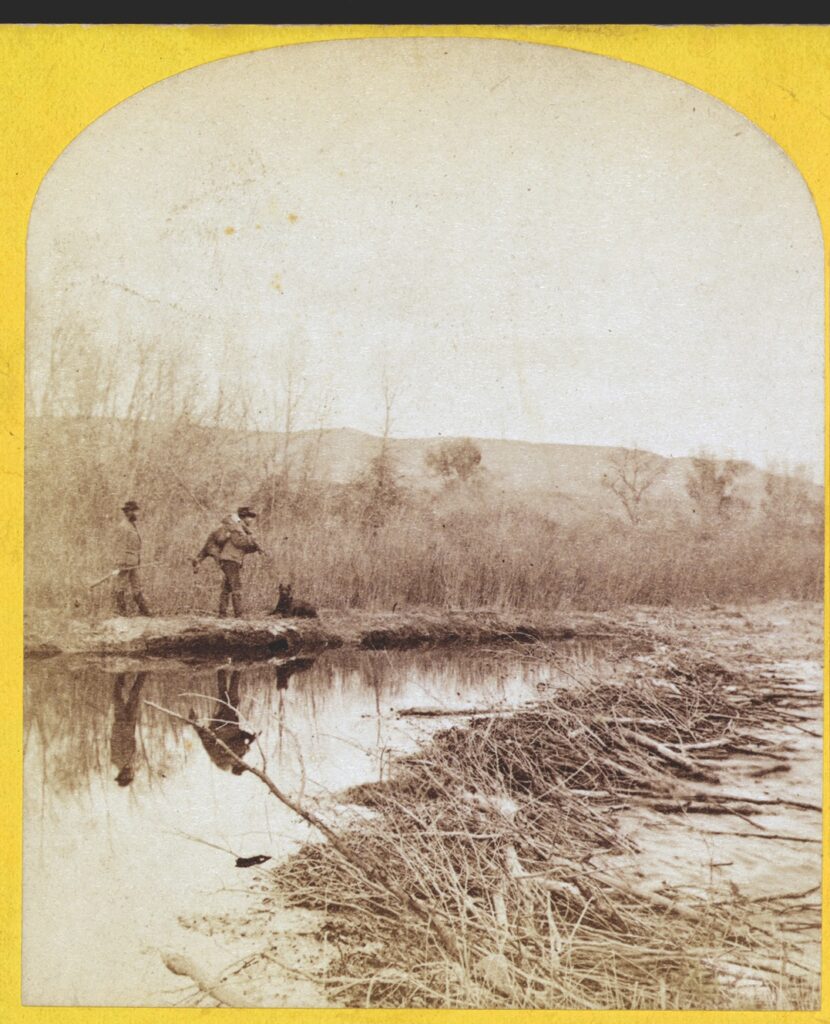

From the beginning, the company owners expected the men working for them to remain in the mountain country during the winter. This allowed them to trap throughout the late fall, and they could then be ready to set traps again in the early spring when the beaver pelts were in their prime.

American Fur Trade Roots

America’s involvement in the fur trade began shortly after Meriwether Lewis and William Clark with their Corps of Discovery returned to the upper Missouri River in the summer of 1806.

Early in the morning of August 12, 1806, Lewis encountered Joseph Dickson and Forest Hancock, two American trappers who were headed up the Missouri, intent on catching beaver. They had come from Illinois and were the harbingers of the American fur trappers. This meeting with Lewis and his men was fortuitous as the would-be trappers gained firsthand information about the country to the west and the opportunities for fur trapping. As a result, Dickson and Hancock reversed their course of travel and headed back downstream with Lewis. They overtook William Clark and his party, who had been following the Yellowstone River, and two days later, the combined group was at the grand village of the Hidatsa.

When Lewis and Clark left the Hidatsa village and continued downstream to St. Louis, one of their key hunters, John Colter, stayed behind. He had been granted permission to travel back into the Rocky Mountain region with Dickson and Hancock. Colter eventually reached the area of Yellowstone National Park and had a near-deadly encounter with Blackfoot warriors in what is now Montana before eventually heading back down the Missouri.

Other American trappers included those who worked for the American Fur Company, which was started by John Jacob Astor after 1811. Those trappers all gathered furs and traded them at posts built at key locations.

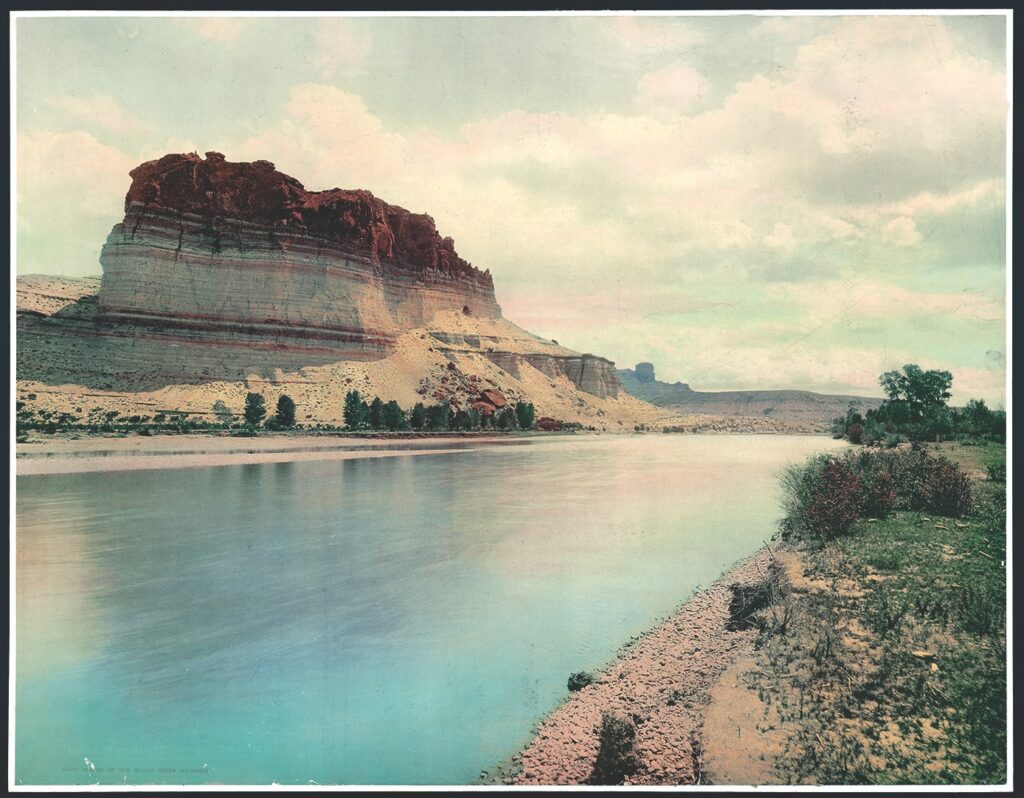

It took the organized operation of Ashley and Henry with their Rocky Mountain Fur Company to revolutionize the American fur trade. Their men spread not only on the Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers, but also across the Continental Divide to work along the streams of the Green River, Snake River and Bear River basins.

Like other trappers working for Astor’s American Fur and the British Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC), during the first two years of operation, the men working for Rocky Mountain Fur traveled annually to fixed posts to obtain ammunition, food supplies and other goods needed in their quest for beaver. The need to travel to the fixed posts required arduous, sometimes dangerous journeys.

But then in the summer of 1825, General Ashley, always seeking to maximize company profits, spread the word for the men working for the company to meet him at a location in what is now southwest Wyoming. In St. Louis, Ashley organized a caravan of horses, loaded packs with the traps, firearms, bullets, black powder, food and other goods the trappers would need. Instead of the company men going to the fixed posts, he went to them.

The first fur supply caravan reached Ren-dezvous Creek, what was later called Henry’s Fork of the Green River, for a trading session that took place July 1, 1825. Around 125 men, “assembled in two camps near each other about 20 miles distant from the place appointed by me as a general rendezvous,” Ashley recalled later that year.

That one-day event was all business. The next day Ashley and some 50 men with him loaded the furs onto their pack animals and set off for St. Louis.

This first rendezvous eliminated the need for the trappers to travel hundreds of miles to fixed site posts to obtain supplies. It completely revolutionized the beaver trade and gave the West an iconic event that is celebrated to this day, just shy of 200 years later.

Although it was a short gathering intended strictly for an exchange of goods, the rendezvous set the stage for the next 15 years. The second, third and fourth rendezvous took place in Cache Valley and near Bear Lake, in today’s Utah, even though in 1828 the fur caravan was extremely late, not arriving until late fall.

The trade rendezvous in 1829 took place farther north in an area called Pierre’s Hole, which is in the Teton Valley near Driggs, Idaho. The 1830 gathering moved into the central Rocky Mountains along the Popo Agie River in the Wind River Basin, at the edge of present-day Riverton, Wyoming.

No true rendezvous took place in 1831, though some trappers gathered in Cache Valley again. But the supply train managed by Thomas Fitzpatrick never made it to the site. Late in the summer, Henry Fraeb located Fitzpatrick, and then Fraeb spent much of the fall delivering goods to the trappers who had already spread out to their favorite beaver streams.

Fitzpatrick was delayed again in 1832 by an encounter with seemingly hostile Blackfoot and Gros Ventre warriors, but William Sublette arrived at the rendezvous location in Pierre’s Hole and began distributing goods, picking up pelts from the free trappers as well as some company men.

Once the trading concluded, the trappers set off to return to fur trapping haunts, but before Milton Sublette traveled far his group of men encountered Blackfoot and Gros Ventre leading to a fight that became known as the Battle of Pierre’s Hole. This was the only rendezvous that involved hostile interactions with tribal members.

Captain Benjamin L. E. Bonneville, a bald thirty-seven-year-old French-born West Point graduate, took a two-year leave from the U.S. Army in 1832 to explore in the West and determine American fur trade potential in the Rocky Mountain region, even though the trade was already well established.

Bonneville began his explorations in Independence, Missouri, on May 1, traveling to Pierre’s Hole and the rendezvous there. Accompanying him were 110 men and several wagons, which are believed to have been the first wagons to cross South Pass. After the rendezvous, Bonneville continued traveling west, exploring areas that are now Idaho and Oregon, before he returned to the region just west of South Pass.

In the Green River Valley above the confluence of Horse Creek, the captain established a fort that took his name—Fort Bonneville—but was soon called Fort Nonsense or Bonneville’s Folly. The two names arose from the fact that although the Green River Valley with its abundant grasslands and available water in the river valley seemed to be an ideal location in the summer and fall, the winters were harsh. Bonneville soon learned that the extremely cold weather and deep snow in that region made movement difficult and limited the availability of wild game. Despite the weather issues, Fort Bonneville was in use until 1839.

Meet Me on the Green

The well-watered region in the Upper Green River Basin became the most popular rendezvous site with seven gatherings held there between 1833 and 1840.

From the first rendezvous of around 125 men, the annual summer gathering grew exponentially to more than 2,000 people. It also expanded from a trapper gathering to one that involved Indian tribes who were allies of the mountain men. Though it was started for the practical reason of trading for necessary supplies, rendezvous quickly became a raucous gathering. As one historian put it, rendezvous was “one hell of a party.”

Originally called Ashley’s Hundred, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company was in fierce competition with John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company and the long-established British Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC).

But for a week or two every summer, generally in July ,“The three rival companies, which, for a year past had been endeavoring to out-trade, out-trap and out-wit each other, were here encamped in close proximity, awaiting their annual supplies. About four miles from the rendezvous of Captain Bonneville was that of the American Fur Company, hard by which, was that also of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company,” according to Washington Irving writing of the 1833 Horse Creek rendezvous in The Adventures of Captain Bonneville.

Since rendezvous involved all the free trappers and the competing companies, it was well known that the first brigade to arrive with supplies had “the greatest chance to get all the peltries and furs of the Indians and free trappers, and to engage their services for the next season,” Irving wrote.

Given the competition for furs, it might be expected that there would be hard feelings, even hostility or outright brawls, when the trappers came together at the rendezvous. But from mid-June until early September, when no trapping took place, they drank, sang and whooped it up. They “tried to out-brag and out-lie each other in stories of their adventures and achievements,” Irving wrote.

Each year the trappers started gathering before the fur brigade with its pack animals arrived, so rendezvous was in full swing when the first trader packs were unloaded and broken open. The trading was soon fast and furious. The free trappers made extravagant purchases of traps, hunting knives, ammunition, guns, red blankets and scarlet cloth, as well as glittering trinkets and garish beads. They bought coffee and tobacco.

Opening the West

Without doubt the most momentous event of the rendezvous era occurred in 1836 when the fur brigade arrived on the Upper Green River with two White women. They were Narcissa Prentiss Whitman and Eliza Spalding, who were traveling to new homes they would establish in Oregon Country with their missionary husbands, Dr. Marcus Whitman and the Reverend Henry Spalding.

They set out from the Missouri River with a light Dearborn wagon that belonged to Eliza Spalding and a freight wagon hauling goods and supplies. Although there were several in their group, they traveled with the fur brigade, which not only knew the route, but also afforded a measure of security as they moved across Indians lands.

Fort Laramie had not been built when the Whitman-Spalding party passed through, but an earlier establishment, a fur trade post that originated as Fort John and later became Fort William, served travelers.

At Fort William the fur caravan left its wagons and repacked the supplies onto horses and mules. The missionaries abandoned their large wagon, too, putting as much as they could on the lighter Dearborn wagon. From this point the two women rode horseback on the sidesaddles they had brought for that purpose. They were proving their determination and mettle to their husbands and the fur traders with whom they traveled.

On July 4, 1836, Eliza Spalding wrote in her diary that they “crossed a ridge of land today called the divide; which separated the waters that flow into the Atlantic from those that flow into the Pacific.”

Days later as they approached the rendezvous grounds, a welcoming party raced out to greet them.

Narcissa Whitman would later write to her family, “As soon as I alighted from my horse I was met by a company of matron [Indian] women. One after another shaking hands and salluting me with a most hearty kiss. This was unexpected and affected me very much. They gave Sister Spaulding the same salutation. After we had been seated awhile in the midst of the gazing throng, one of the chiefs whom we had seen before came with his wife and very politely introduced her to us.”

She added, “They say they all like us very much and thank God that they have seen us, and that we have come to live with them.”

Headed for the Place of the Rye Grass

After a sojourn at the rendezvous, Nez Perce guides took the missionary party on west. Hudson’s Bay Company trader Nathaniel Wyeth established Fort Hall in 1834 on the Portneuf River of southeastern Idaho. There Dr. Whitman modified the Dearborn wagon into a two-wheeled cart to continue hauling their gear over the rough country, as there was not much of a trail to follow.

The missionaries followed the Snake River to Farewell Bend, Oregon, before continuing north over the Blue Mountains to present Walla Walla, Washington, where the Whitmans established their Whitman Mission—Waiilatpu—the Place of the Rye Grass, to serve the Cayuse tribes.

The Spaldings followed the Clearwater River to its confluence with Lapwai Creek. There they established a mission they called Lapwai, known to the Indians as the Place of the Butterflies. It lay in the heart of Nez Perce country at a site long used as a tribal winter camp.

Rendezvous in 1837 took place on the Green River, between the New Fork and Horse Creek. Then in 1838 the trappers gathered on the Popo Agie, near the same site as the 1830 rendezvous. By then the men realized that their mountain trade was in decline. The styles of men’s hats had shifted from beaver to silk and the fashion trend impacted the need for beaver pelts.

The mountain men held two more rendezvous, both along Horse Creek, a tributary of the Upper Green River. Jim Bridger, Henry Fraeb and Andrew Drips guided the last caravan from the settlements along the Missouri River to Horse Creek in 1840.

There would be no more company brigades and mountain man rendezvous. The country was changing. Instead of seeking to dominate the region through trade, the Americans set out to control the region through settlement. Wagons had already crossed South Pass, and the journey of Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding made it clear women could make the long journey from the Missouri River to the Oregon Territory.

The Bidwell-Bartleson wagon train traveled to Oregon Territory in 1841, but the first large wagon train followed the route that would become the Oregon Trail in 1843. During the next 20-plus years well over 500,000 people crossed the region on the Oregon, California and Mormon Trails. In those earliest years, the wagon trains were guided by the mountain men who knew the region so well. Throughout the period and beyond, the trading post started by Jim Bridger and Louis Vasquez that became known as Fort Bridger, was an important trade post on the trails.

Men who were a part of Ashley’s One Hundred left their mark on many other areas across the region including such well-known places as the Fitzpatrick Wilderness, Sublette County and Jackson Hole. The era of rendezvous, which marks its bicentennial in 2025, died out. But the experience is revived each year at modern-day mountain man gatherings across the West, including the annual Green River Rendezvous the second weekend in July, and the largest annual gathering at Fort Bridger over Labor Day Weekend.

Rendezvous Locations

1825 – Henry’s Fork of the Green River (Burnt Fork, Wyoming)

1826 – Cache Valley (Willow, Utah)

1827 – Bear Lake (Utah)

1828 — Bear Lake (Utah)

1829 – Pierre’s Hole (Driggs, Idaho)

1830 – Popo Agie (Riverton, Wyoming)

1831 – No true rendezvous; men gathered at Willow, Utah; Thomas Fitzpatrick’s supply train never arrived; Henry Fraeb finds Fitzpatrick and spends the fall delivering goods to the trappers

1832 – Pierre’s Hole (Driggs, Idaho)

1833 – Horse Creek (Pinedale, Wyoming)

1834 – Near Granger, Wyoming

1835 – Fort Bonneville (Pinedale, Wyoming)

1836 – Horse Creek (Pinedale, Wyoming)

1837 – Green River, between Horse Creek and the New Fork River (Pinedale, Wyoming)

1838 – Popo Agie (Riverton, Wyoming

1839 – Green River (Pinedale, Wyoming)

1840 – Green River (Pinedale, Wyoming)