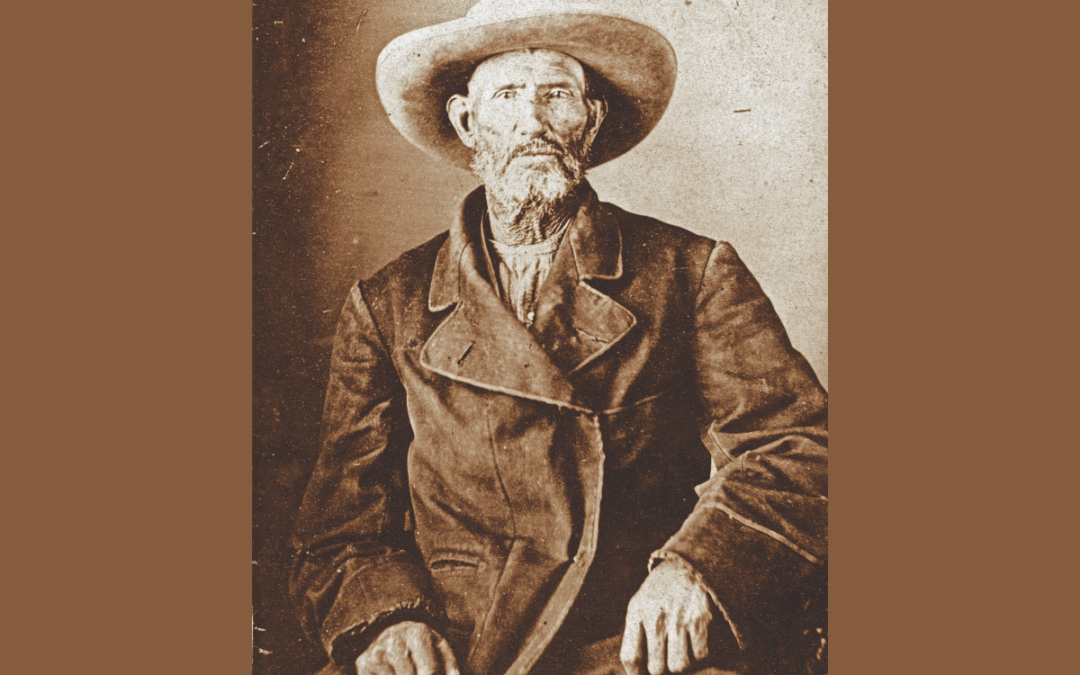

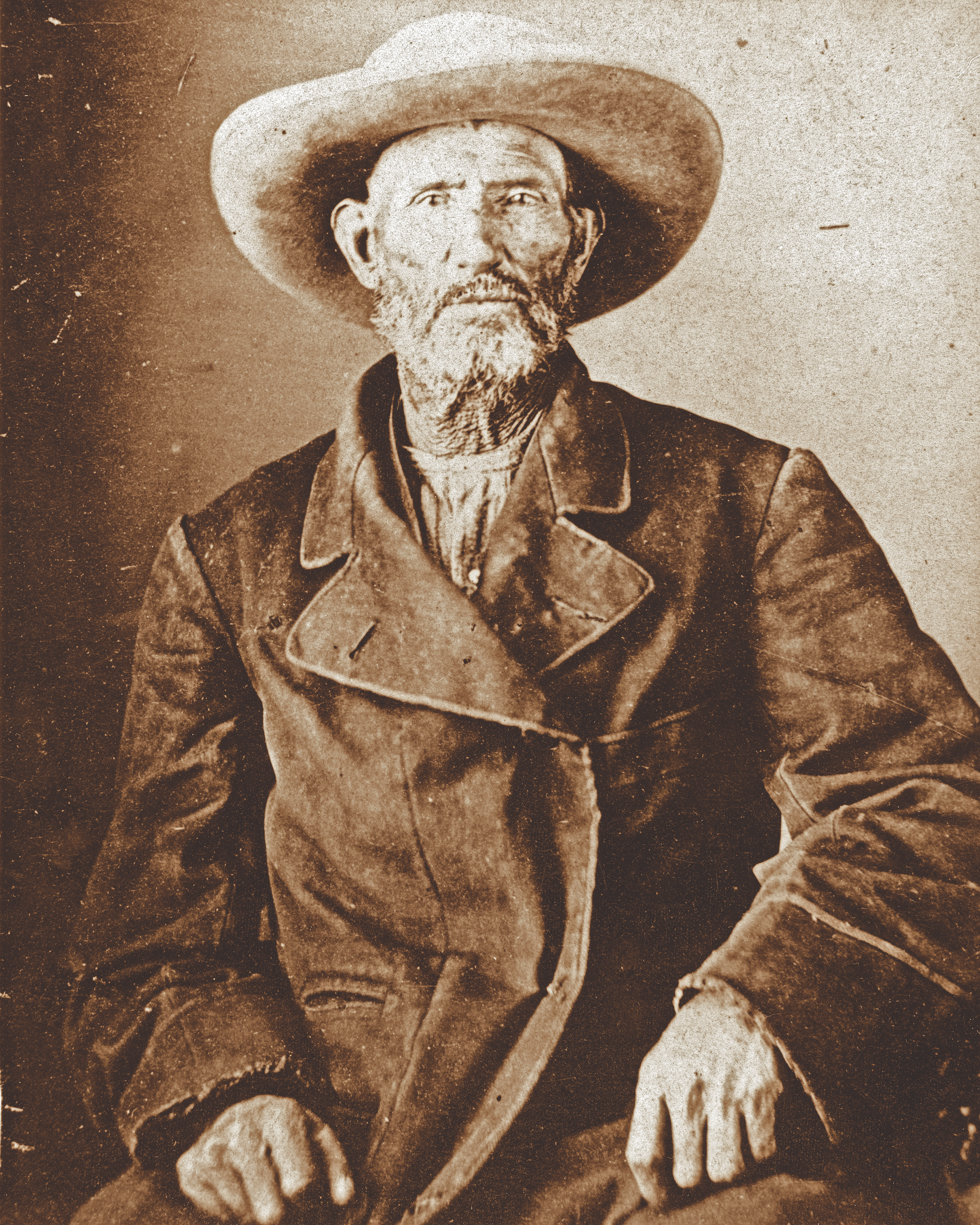

Pathfinder Jim Bridger tangles with

Prophet Brigham Young

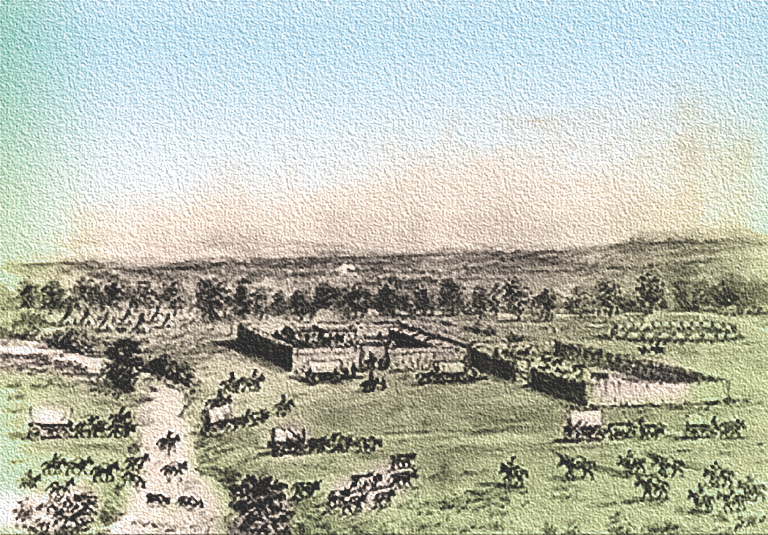

Jim Bridger was one of the most skilled mountain men in American history. In 1822, when he was 18, he joined Andrew Henry and William Ashley’s Enterprising Young Men “to ascend the river Missouri to its source, there to be employed for one, two or three years.” After 21 years, he decided it was time to build a more permanent home. In 1843 he and his partner, Louis Vasquez, built Fort Bridger on Blacks Fork of the Green River. It was an oasis, with mountain trout swimming in gurgling streams, “beautiful out of all reason, like a charming but improbable stage setting with the snow-topped Uinta Mountains to the south.” Bridger could neither read nor write, but a scribe wrote this for him: “I have established a small store with a Black Smith shop, and a supply of Iron in the road of the immigrants on Black’s Fork, Green River, which promises fairly. They [the emigrants] in coming out, are generally well supplied with money, but by the time they get there, are in want of all kinds of supplies. Horses, Provisions, Smith work, &c. brings ready Cash from them and should I receive the goods hereby ordered [I] will do a considerable business in that way with them.“

BRIDGER AND YOUNG MEET

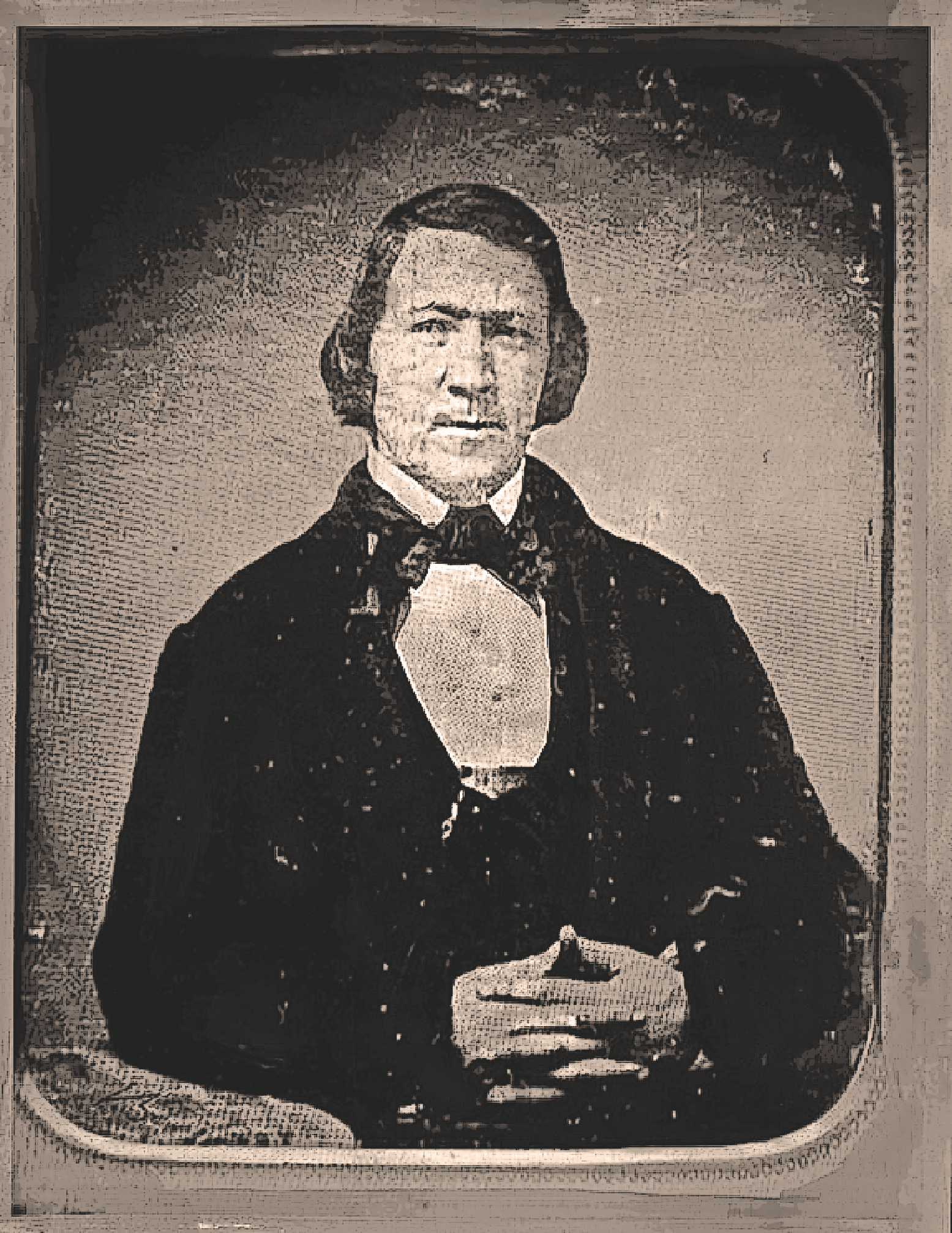

In 1847, Bridger was traveling with two of his men near the Little Sandy where it flowed into Green River, and he saw a large group of pioneers moving west.There were 143 of them, an advance party of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) led by Brigham Young. He was likened to an American Moses trying to find a place where his people wouldn’t be persecuted. Violent Americans had run them out of Palmyra, New York; Kirtland, Ohio; Independence, Missouri; and Nauvoo, Illinois. Jim Bridger and Brigham Young seemed to get along well, and they prepared to camp their men together that night. Young was interested in settling in the Great Basin in Mexico, away from the United States. Young hoped Bridger would guide them over the Wasatch Range, but Bridger said he couldn’t because he was going to Fort Laramie, where “the Upper Gentry want to take advantage of me” about a delivery of beaver pelts. Bridger described the land they would encounter, but Mormon Howard Egan did not believe what Bridger said. “From his appearance and conversation, I should not take him to be a man of truth…. It is my opinion that he spoke not knowing the place.” Mormon William Woodruff, a future president of the LDS church, had more belief in the mountain man, writing that he “found him to be a great traveller, possessing an extensive knowledge of nearly all of Oregon and California…. Bridger said it [the basin] was his Paradise, and that if these people settled in it he would settle with them.”

The next morning, Bridger was impressed when the Mormons prepared breakfast, and he remarked, “There is more bread on the table than I have before seen for years…. We live entirely on meat. We dry our deer and buffalo to eat, and also cook fresh when we can obtain it.” The mountain man invited the Mormon party to stop at his fort. Although his blacksmith shop had recently burned down, Bridger said they could use the anvil to shoe their horses and repair wagons.

Young gave Bridger a pass to use a ferry that the Mormons built to cross the Little Sandy. The Mormons struggled through a difficult crossing over the Wasatch, and when they finally reached Salt Lake Valley, Young declared, “This is the place.”

Young had every right to protect his people from persecution. He told them, “We do not intend to have any trade or commerce with the gentile world…. I am determined to cut every thread of this kind and live free and independent, untrammeled by any of these detestable customs and practices.” The Mormons built their home there and began to prosper. But the very next year the Mexican-American War ended. Brigham Young’s settlement and Bridger’s fort became part of the United States. Young still remembered what he had said to his people when they set out toward the West: ”We don’t calculate to go under any government but the government of God. There are millions of the Laminates [Indians] who, when they understand the law of God and the designs of the gospel, are perfectly capable of using up [killing] these United States. They will walk through them and leave them waste [dead].”

Tensions arose when Bridger learned that Young thought he was encouraging Indians to attack the Mormons. Bridger had someone write this letter addressed to ”The President of the Salt Lake Valley” and dated July 16, 1848:

“I am truly sorry that you should believe any reports about me having said that I would bring any Indians or any number of Indians upon you or any of your Community. Such a thought never entered my head…. Believe Mr. President, I am desirous of maintaining an amicable friendship with the people in the valley and should you want a favour at my hands at any time I shall always think myself happy in doing it for you. From your Friend and well wisher James Bridger.”

The July letter appears to have calmed Young and in December he wrote Bridger and Vasquez that he was open to their advice. In April Vasquez wrote the Mormon leader that he should be careful sending Mormons out to establish new settlements. The Indians “are badly disposed toward the whites…. They have been fighting with some Americans in the direction of Taos, and there have been sum of them kild, and to mind the matter, you have killed four this Spring. Last October, Mr. Bridger was at the Uinta for the purpose of staying the winter with them. Their conduct alarmed him so that he had to return to this place to winter.” Vasquez wrote Young that the Bannock Indians think a Mormon murdered one of their people, stole two horses and the Indians might attack Salt Lake City. The council read Vasquez’s letter out loud, and Young surprised them by declaring, “I believe I know that Old Bridger is death on us, and if he knew 400,000 Indians were coming against us, and any man were to let us know, he would cut his throat.” While the “President of the Salt Lake Valley” spoke fondly of Vasquez, he appears to have selected Bridger as a target for wrath. He announced to his council, “I believe Bridger is watching every movement of the Mormons, and reporting to [Senator] Thomas Benton at Washington. As to the affair [murder and stolen horses] it is a backhanded man that can’t be understood. That letter is all bubble and froth. Bridger and the other mountaineers were the real cause of the Indians being incensed against the Saints, if they really were incensed.” Peg-Leg Smith, who was not on good terms with Bridger, told Young that a Bannock was not killed, it was a Shoshone. Smith said Bridger and Vasquez did not kill the Indian because they “were not brave enough, but they may have caused it to be done, to bring on a fuss between the Indians and our people, Bridger and Vasquez being jeaalous of them [Mormons] trading with the Indians.” Salt Lake City continued to grow with the addition of 1,500 Mormons in 1849. By 1850, the city had mills, stores, schools, factories, blacksmiths and dentists. While Brigham Young had initially wanted to avoid trade with the “gentile world,” he allowed gentile merchants Louis Vasquez and Livingston & Kinkead to open their stores there.

FORCED OUT

There were several conflicts between Salt Lake City authorities and Bridger and the other mountaineers. One law required that brands on livestock had to be reversed when sold. In 1852, four men each purchased a horse from Fort Bridger without reversed brands, and Utah officials seized their horses. The men had no choice but to sue Bridger and Vasquez, which they did for the amazing sum of $35,000. Arbitrators reduced it to $904, still almost three times what the horses were worth. The number of emigrants traveling west more than doubled, with 60,000 travelers in 1852. Green River ferries became very profitable, and in January 1852, the Utah territorial legislature gave Green River ferry rights to Thomas Moor for one year. In 1853, the legislators gave Daniel Wells an exclusive three-year charter for the ferries. Bridger and other mountaineers had established Green River ferries through relationships with the Shoshones. When Brigham Young and his legislators passed laws pertaining to ferries, it disturbed both mountaineers and Indians. Many Mormons had moved to southern Utah against the wishes of several Utes. Ute strongman Walkara attacked several church settlements, and Governor Young suspended all licenses to trade with the Shoshones, Utes and other Indians. Young also suspended Tavern Keeper licenses for Fort Bridger and Green River, which had been granted by U.S. Ute Indian Agent Jacob Holman.

Bridger did not support Indian treachery. But on August 17, 1853, Utah Judge Leonidas Shaver issued a writ for Bridger’s arrest, stating that he “on the 1st day of August 1853 unlawfully aided and abetted the Ute Indians, and supplied them with arms and ammunition for the purpose of committing depredation upon and making war on the citizens of the United States.”

Mormon Bill Hickman described it this way. “It was rumored that Jim Bridger was furnishing the Indians with powder and lead to kill Mormons. Affidavits were filled out to that effect, and the sheriff was ordered out with posse.”

The charge was treason and could be punished with death. Governor Brigham Young was the master planner for the “Ft Bridger and Green River Expedition.” He instructed James Ferguson to “raise fifty men fully equipped for service with rations for twenty days.”

Bridger found a concealed spot and, with a spyglass, kept an eye on his wife, Mary, and the large militia. The militia were unable to capture Bridger, and the attorney for Utah Territory, Seth Blair, suggested a scheme to have several people sue the mountain man for damages and confiscate the fort to cover payment. He said, “I can draw up declarations and forward them in & the Surpoenas can be Sent out & coppies left at his Residence & it is most probable–that judgment will go by default.”

Judge Shaver said Blair’s scheme would not work to get his fort, but they might take his fort if they charged Bridger for selling “spiritous liquors” and rum to Indians. Young suggested that Ferguson befriend Washakie who might be “influenced to bring Mr. Bridger in, or to give some information concerning his whereabouts.”

Bill Hickman was part of a posse that rode to Green River and killed two or three mountaineers operating the ferries. He remembered it was a bloody job that left him scarred in mind and body. The posse reported, “Bridger was either gone for good or, if he returned, his influence would be diminished.”

The posse occupied the fort for two months and confiscated 400 to 500 head of stock as well as anvil, iron, guns, powder, steel and foodstuffs. They inventoried the total at $2,736. Strangely, the inventory was signed and verified with “given under my hand this 25th day of February 1854. James Bridger.” But James Bridger could not have signed it, as he was in Washington, D.C. in February 1854. The Mormons tried to keep Fort Bridger, but they were repelled by mountaineers, and the Mormons established Fort Supply about 12 miles southwest instead.

By this time, Bridger was considered a national icon, and several newspapers wrote articles about him. The famous mountaineer headed east with his family to Westport, Missouri, to find a home for winter. On Christmas Day he set out for Washington, D.C., where he asked Secretary of War Jefferson Davis to submit his claim to President Franklin Pierce. Bridger’s lawyer said, “Mr. Bridger utterly denies that he has, in any instance, violated the laws in question and alleges that the process of the Court was improperly obtained, irregular in form, and illegal in substance.” Davis forwarded the petition to the attorney general of the United States, Caleb Cushing.

Bridger brought his case to members of Congress and implored help from Sen. Stephen Douglas. His committee was suggesting a bill to transfer the Fort Bridger and Green River area to Nebraska. Brigham Young was livid and wrote to Douglas that Bridger “had become the oracle to Congress in all matters pertaining to Utah.”

But Bridger was not able to win the day. Jefferson Davis wrote that the president had no authority to entertain Bridger’s claim. The Kansas-Nebraska Act passed and Fort Bridger and Green River were still part of Utah Territory. Bridger came back to his new home, Westport, Missouri, and tried to make sense of his new world. He missed the mountains and people like Washakie.

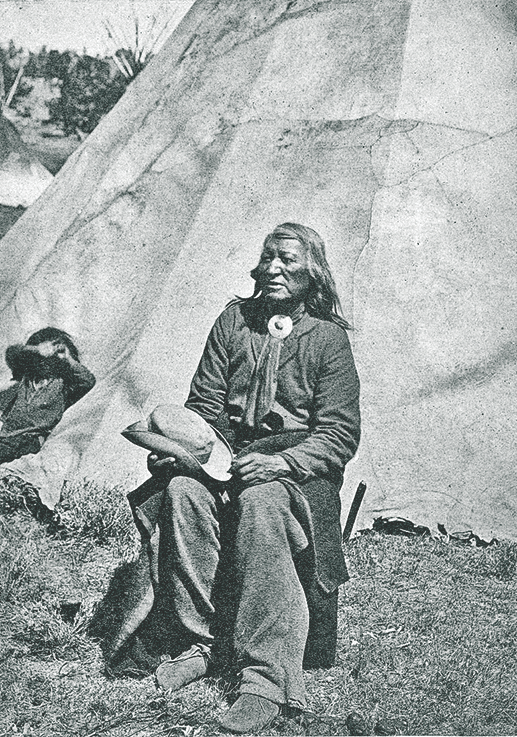

Washakie missed Bridger. In June the Shoshones were upset over “Bridgers being runoff who always had furnished them with such things as they needed.” Washakie was at the Green River ferries, showing his anger at the Mormons: “This is my country, and my people’s country. My fathers lived here, and drank water from this river, while our ponies grazed on these bottoms. Our mothers gathered the dry wood from this land.”

In response Brigham Young wrote to Washakie that Bridger should not have hidden from the posse. If he had not “fled or resisted the officers but stood his track, perhaps he might have got clear and not even been fined.” Bridger could not be sure that was true.

In the summer of 1855, James Bridger was back in the mountains guiding Sir St. George Gore, an adventurer from Sligo, Ireland. At the same time, he was wondering if he could ever reclaim his fort. Was the warrant for his arrest still standing? He rode to Fort Bridger and met Green River County Sheriff Bill Hickman who found Bridger “verry carless and indeferent about Selling.” The mountaineers encouraged Bridger to hold on, saying that “he had better keep the Place.”

Lewis Robison was a purchasing agent for the Mormon Church, and he hoped to close a deal. With funds from the church, he offered to buy the fort for less than the $8,000 they had discussed. Bridger held firm, and they finally agreed on $4,000 in August 1855 and $4,000 in November 1856.

Bill Hickman was there with the men who carried the heavy gold which was marked “United States Assay Office of Gold San Francisco California.” Attorney H. F. Morrell signed for Louis Vasquez, and Bridger marked his X. The deal was done. When Mormon official Heber Kimball heard of the deal, he wrote to an acquaintance in England with the message: “The Church has bought out Bridger Ranch…. Bridger is gone.”

THE UTAH WAR

John C. Fremont ran in the 1856 presidential election on a stance to abolish the “twin relics of barbarism: slavery and polygamy.” Stephen Douglas, hoping to be the Democratic nominee, called plural marriage “an ulcer in the land that had to be cut out.” The federally appointed Utah surveyor general, David Burr, said, “These people repudiate the authority of the United States…and are an open rebellion against the general government.”

The Mormons wanted to control Utah Territory with religious leaders. Brigham Young said he would “sooner see any Gentile from the States buried deep in hell before he would relieve him from starving; let them all die the death of dogs,” according to the Chicago Tribune.

James Buchanan won the presidency and appointed Alfred Cumming, not a Mormon, as the new governor of Utah Territory. Buchanan ordered up to 2,500 troops under Gen. William S. Harney to escort Cumming to Utah. Brigham Young vowed, “If Harney crossed the South Pass the buzzards Should pick his bones. The feeling of Mobocracy is rife in the ‘States’ the constant cry is killed the Mormons. Let them try it.” Mormon leader Heber Kimball said, “God almighty helping me, I will fight until there is not a drop of blood in my veins. Good God! I have wives enough to whip out the United States.”

The country was ready for war, and the U.S. Army hired Brigham Young’s nemesis, Jim Bridger, to be the chief scout. It the largest assembly of troops in the United States at that time. Jim Bridger began leading the first federal troops toward the mountains on September 3, 1857.

These were dangerous times in Utah. Brigham Young preached the practice of “blood atonement” for faltering Mormons, and some were so grievous that the sinner should beg their brethren “to have their blood spilt upon the ground…as an offering for their sins.… Will you love that man or woman [who has committed sin] well enough to shed their blood?…. This is loving our neighbor as ourselves.” For those who violated church covenants, he said, “The blood of Christ will never wipe that out; your own blood must atone for it.”

In southern Utah, the Fancher and Baker wagon train from Arkansas was being attacked on September 11 at Mountain Meadows, not only by the Paiutes but by local Mormons. John Lee was ordered to “decoy the emigrants from their position and kill all of them that could talk.” Lee led a group of Mormon militia as if they were coming to the emigrants’ rescue. The emigrants lowered their rifles and then were killed. Although some accused Young of orchestrating the murders that occurred at the Mountain Meadows Massacre, historical evidence demonstrates that the almost-unthinkable tragedy was perpetrated at the behest of local Latter-day Saint leaders. Brigham’s orders to let the emigrants go unharmed arrived too late.

Bridger guided Col. Edmund Alexander and his troops to Hams Fork, then returned to Laramie to guide Col. Albert Sidney Johnston, the overall commander. The army troops and supply trains were spread out over the Oregon Trail. The travelers soon learned that snow came early to the mountains. Maj. Fitz. John Porter recorded:

“Near the Rocky Mountains, snowstorms began to overtake us, but Bridger, the faithful and experienced guide, ever on the alert, would point in time to the ‘Snow-boats’ which, like balloons sailing from the snowcapped mountains, warned us of storms; and would hasten to a good and early camp in time for shelter before the tempest broke upon us. At South Pass a cold and driving snowstorm barred progress for a few days, but permitted the gathering of trains, which assured protection.”

Washakie was at South Pass and said Brigham Young had asked them to fight the soldiers, even suggesting the army might kill the Shoshones after they annihilated the Mormons. Washakie said the Shoshones could fight for the army, and Johnston refused. They should not have anything to do with the conflict.

Brigham Young discouraged Mormon engagement with the federal troops if faced with a dangerous threat. He ordered them to “annoy them in every possible way…. Stampede their animals and set fire to their trains. Burn the whole country before them and on their flanks. Keep them from sleeping by night surprises, blockade the roads by falling trees and destroying fords… Set fire to the grass on their windward.”

Mormon Lot Smith and his raiders attempted to burn much of the forage between South Pass and Fort Bridger. When Smith encountered a federal supply train, the U.S. Army captain pleaded, “For God’s sake don’t burn the trains!” Smith responded, “It’s for His sake I am going to burn them.”

Colonel Johnston and Colonel Alexander joined forces at Hams Fork. Bridger told them they should move to Blacks Fork for less wind and more timber. Colonel Johnston was very pleased with Bridger’s foresight, and that evening he gave Bridger the title of major. When they did reach Blacks Fork, they found that the Mormons had burned Fort Bridger to the ground so the army could not use it.

Shortly after he saw the burnt fort, Bridger walked up the hills overlooking the valley. He saw the trees along Blacks Fork and the distant outline of the Wind River Mountains. Capt. John Phelps was also looking at the countryside and was moved when he saw the old mountaineer standing by himself looking pensively at the land that had once been his. He wrote:“It is 35 years since he first came here…. He traded with the Indians, sending the furs which they brought from the mountains to St. Louis once a year and returning with a supply of goods…. He was a perfect monarch of all he surveyed, at one time having the control of 500 men, and never dreamed that his kingdom would ever be disturbed….so remote was it from the United States…. But the Mormons came. Mr. Bridgers reign was ended. They seized upon this point and ejected its ancient owner.”

With spring approaching, the passes were suddenly open. Bridger had spent years traveling through this country and probably knew it better than anyone. He met with Colonel Johnston several times to strategize how and when to cross the mountains to Salt Lake City.

Brigham Young had said many times that he would never let the gentiles take their city. But he was defeated and could not thwart the army. Young invited Cumming to cross the mountains ahead of the soldiers, and at the same time Young evacuated the city. The new governor entered Salt Lake City on April 12, 1858, and the former governor hoped it did not look like a defeat.

Colonel Johnston, marching his troops through Echo Canyon, insisted the army would march through the empty city with the sounds of “the music of the military bands, the monotonous tramp of regiments, and the rattle of the baggage wagons.” When the army finished its march, it camped on the west side of the Jordan River.

Brigham Young’s dream of a theocracy was over. Jim Bridger carried sorrow in his heart for the loss of Fort Bridger.