Before the Myth was penned, The Kid had already become a Legend in Theaters, tabloids and the American Imagination

There is no question that Walter Noble Burns’s The Saga of Billy the Kid broadened William Bonney’s prominence and deepened interest in the outlaw’s exploits when it was published in 1926. The talented writer’s book became a hit from coast to coast, setting off a wave of “Billy fever” that resulted in a motion picture—King Vidor’s Billy the Kid—hitting cinemas in 1930. The author’s enthralling narrative would also inspire a generation of future historians, including Bob Boze Bell and the late Frederick Nolan, to spend decades of their lives pursuing the history that inspired his literary masterpiece.

For many decades now, the general consensus has been that Billy the Kid had fallen off the proverbial radar by 1926. Some of that conviction has come as a result of novelist Harvey Fergusson’s opinion piece that asked the question, “Who remembers Billy the Kid?” when it was published in The American Mercury in 1925. As far as the cynical Fergusson was concerned, the bandido had pretty much been forgotten and would only fade further into obscurity.

The story goes that Walter Noble Burns rescued Billy the Kid from cultural oblivion and transformed him into a household name with the publication of his enchanting book in 1926. It has always made for a nice story. The only problem is; it is not entirely true. While Burns may not have heard about him when visiting Tom Powers’s Coney Island Saloon in El Paso in 1917, Billy the Kid was already a proven box-office attraction and a household name before the author even started typing his manuscript.

BILLY ON STAGE

Since Ancient Greece, long before motion pictures became the world’s primary source of visual entertainment, theatrical productions had set the standard for show business. While Billy the Kid had yet to reach the same level of iconic outlaw status as Jesse James in terms of dime novel numbers and book sales in the early 20th century, fictionalized tales of New Mexico’s most famous bandido were a dependable attraction in theatres for almost two decades.

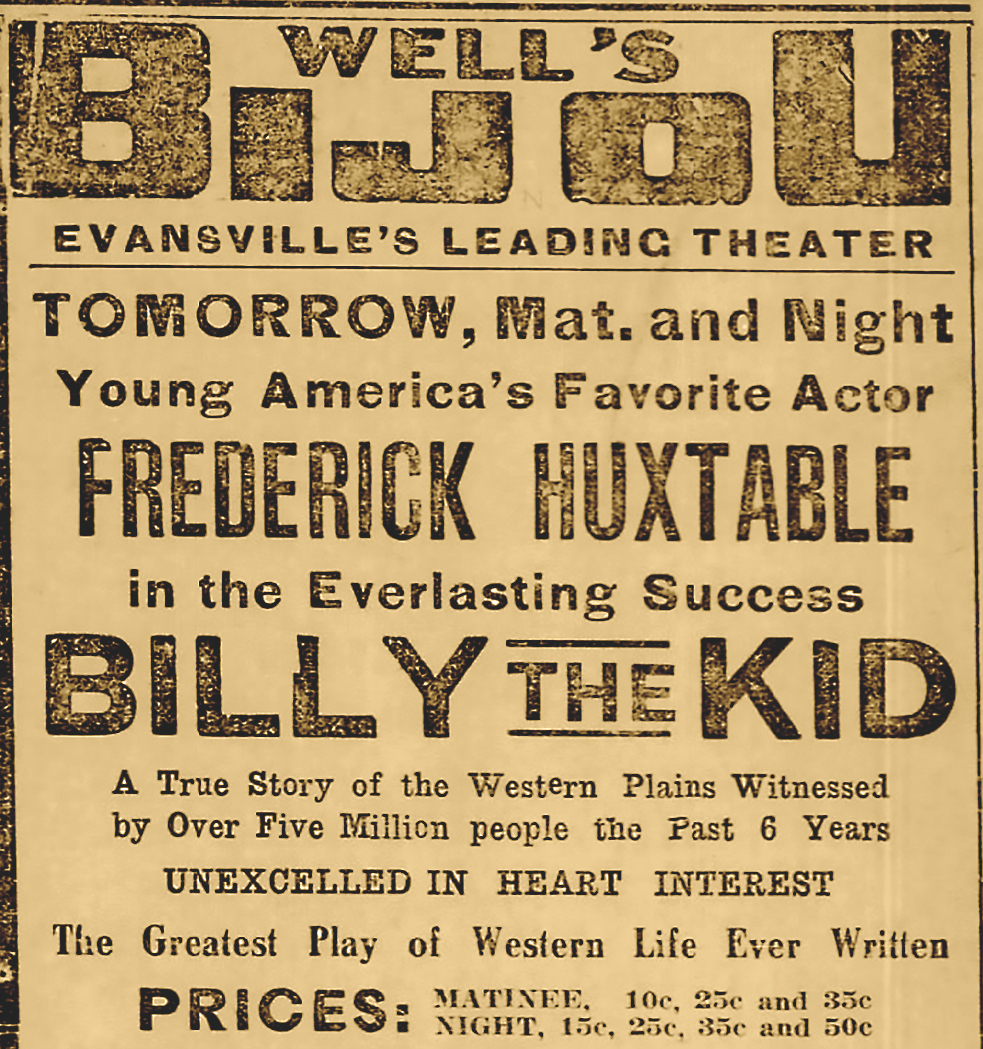

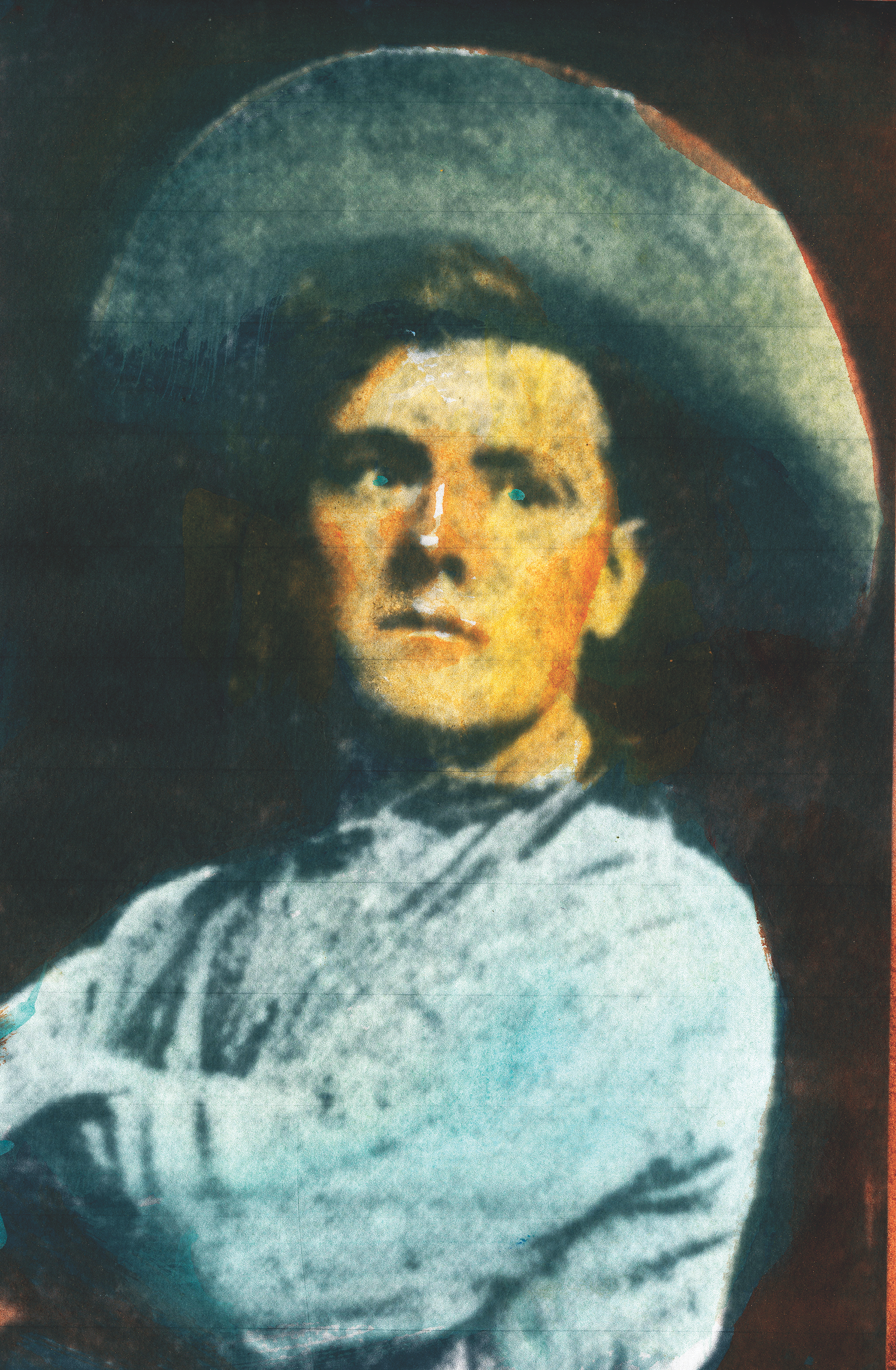

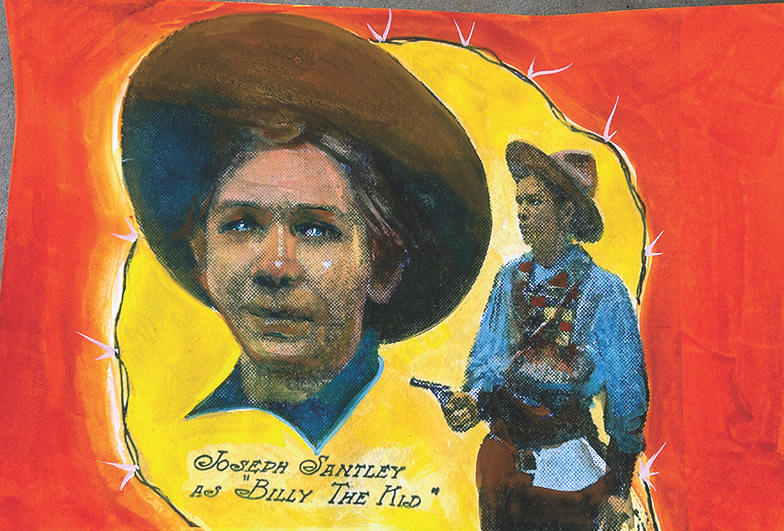

In 1906, a play titled Billy the Kid began drawing large crowds throughout America. The comedy-melodrama written by Joseph Santley and Walter Woods—with the 16-year-old Santley also playing the lead role—caused quite a sensation that year. “Hooray, I have this week seen Billy the Kid,” declared a correspondent in the Chicago Tribune on August 26, 1906. “The theater where this new play is presented holds more people than any other in town and has a larger ratio of boys to men in its audiences. Not less than 10,000 lads will have seen the glorification of juvenile depravity when the week is over.” The production was described as “The Bloodiest Play on the New York Stage” before the show hit the road in New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin and Missouri. “Billy the Kid, as played by a reformed Wall Street messenger boy, is the hottest stuff ever and anywhere,” declared the Saginaw News in Michigan on September 21, 1906.

The appeal of Joseph Santley and Walter Woods’s play showed no sign of dissipating as the production enjoyed further success in 1907. The four-act play was performed in packed houses in New York, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Illinois, Ohio, Indiana, Wisconsin, Missouri, Minnesota, and even in Ontario, British Columbia, and Quebec, Canada. “For a rip-roaring, something-doing-every-minute melodrama, Billy the Kid is all that could be desired,” the Fort Wayne

News and Sentinel declared on January 18, 1907. The hit production made Joseph Santley a star, and photographs of the young actor were published in many newspapers across North America. “Joseph Santley, perhaps the greatest boy actor on stage today, is drawing large audiences,” the Buffalo Courier announced in New York on September 10, 1907.

The demand for Billy the Kid was so strong that another young actor named LeRoy Sumner began playing the lead role in certain cities in place of leading man Santley. “The popular young actor, LeRoy Sumner, has a part which is just suited to his requirements,” the Morris County Chronicle declared in New Jersey on August 13, 1907. Various newspapers provided a summation of the melodrama’s plot for the public, including the Hartford Courant in Connecticut on October 15, 1907:

The story of the play comes from Texas and New Mexico, where Stephen Wright’s son, Billy the Kid, swears an oath of vengeance upon the death of his parents, they having been shot to death by Boyd Denver, an Eastern “gentleman” who had a heart that probably resembled a den of rattlesnakes. Billy goes West and turns desperado. At the “Broken Heart,” Billy meets Denver and his gang of crooks and is surrounded but by clever use of his revolver he escapes after a battle with the men in the dark, taking with him his sweetheart, Nellie Bradley, who with her colored servant, Mose Moore, was held prisoner there. Following this affair Colonel Bradley, the uncle of Nellie, gives a dinner to Billy the Kid and it is attended by Denver and his pals, who hope to kill the kid, who is Denver’s son, the father wishing to gain possession of all the Wright property. Billy gets wise to their antics and takes the role of servant girl, gets the whole bunch drunk and then beats it while his shoes are still good. Followed by the colonel and his niece Billy makes his way to his old home where he finds Denver, who plans to take possession. Accidently shot by a friend, who took him for Billy, the life of the villain comes to a close, Billy marries Nellie and a happy family once again hold forth in the Wright homestead.

The plot was pure fiction, but audiences didn’t care. They just wanted Billy the Kid. One can easily imagine young boys pouring out of the theaters eager to start imitating the vengeful desperado while playing with their friends in the streets.

Billy the Kid was picked up by various production companies and continued to enthral audiences in theaters across the United States and Canada for more than a decade after its 1906 premiere. While Joseph Santley became the star of the musical When Dreams Come True, the role of the good-bad boy Billy was played by various young actors including LeRoy Sumner, Frank Dickson, Nolan Cane, Frederick Huxtable and the popular Berkley Haswell. “Every boy who sees Billy just raves over the bravery displayed against the cowboys, and every girl loves him for the gallantry displayed by Billy as a sweetheart,” the Courier-News proclaimed in New Jersey on October 31, 1912. “Jack London has turned the tide of public sentiment toward western life with his powerful tales of those regions, but nothing from his pen surpasses in pathos and realistic life pictures the situations, portrayed in the play,” declared a press release published by the Hinton Times in West Virginia on November 16, 1912. “Billy the Kid is a good play, better than any western play I ever saw,” declared stage actress Edyth Totten in New York in 1913.

Billy the Kid had recently enjoyed seven seasons of production in New York when playwright James Hoadley wrote a sequel titled Billy the Kid in Mexico in 1920. Berkley Haswell returned to the role, and the production received warm reviews following its premieres in New York and Ontario, Canada, but like many sequels, the play ultimately failed to replicate the sweeping success of its star-making predecessor.

BILLY AND THE PRINTED WORD

While a theatrical production was bringing a largely fictionalized version of Billy the Kid to the masses, the historical William Bonney who had fought in the Lincoln County War was no stranger to the reading public prior to 1926. Almost every year, another feature about the Kid’s often-embellished exploits and his death at the end of Pat Garrett’s revolver was being written and republished in countless newspapers across America, Canada and as far as Australia throughout the early 20th century.

In 1905, Arthur Chapman’s vitriolic and exaggerated article, “Billy the Edith Storey, the first thespian to play “Billy the Kid” on a silver screen, was born in New York City on March 18, 1892. Her film career began in 1908. She played the lead role in Billy the Kid three years later in 1911. “A very fine picture,” the Arkansas City Daily Traveller announced. “It was the story of a girl who from birth had passed as a boy. This picture was enjoyed by the audience.” The Western Comedy film was well-received by other critics and moviegoers across the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. “The girl leads the life of a cowboy until she is 16 years of age, and her sex is discovered through an encounter with a band of outlaws,” the Idaho Statesman declared on September 3, 1911. “This production has many laughable situations. It is both convincing and enjoyable and worth going miles to see.” Edith Storey starred in numerous other silent Western films, including The Immortal Alamo (1911) and As The Sun Went Down (1919), before she retired from acting at the age of 29 in 1921. Having starred in over 140 silent films throughout her career, Storey eventually received a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. Edith worked as a village clerk in Long Island for decades prior to her death in Northport, New York, on October 9, 1967.

Kid: A Man All Bad,” was republished in newspapers throughout Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Alabama, Kansas, Oklahoma, Florida, Nebraska, North Carolina and South Carolina. Snippets of Chapman’s piece were also published in New York, Massachusetts, Iowa and Canada. Another lengthy feature written by journalist Webster Ballinger that focused on the Kid’s famous jailbreak and death ran in the Evening Star (Washington D.C.) on March 4, 1905. That piece was faithfully reproduced in newspapers in Minnesota, Tennessee, North Dakota and Ohio that spring.

The following year, American West writer Allen Kelly published a sympathetic article about William Bonney titled “A Swashbuckler Out of Time” for the San Francisco Chronicle on June 10, 1906. “Born 300 years too late, William Bonney, instead of becoming the hero of an historical novel, was hunted to a death in the dark as the toughest bad man of the west,” Kelly professed. “It was the bad luck of Billy the Kid, cow puncher, to be engaged on the wrong side in the big cattlemen’s feud known as the Lincoln County War.” The Province in Vancouver,

Canada, republished Kelly’s piece for its readers later that month.

1907 saw the publication of Emerson Hough’s preachy book Story of the Outlaw, in which Billy was a prominent figure. The name Billy the Kid and his outlaw exploits were again all over the newspapers when Pat Garrett’s death was reported across America in 1908. Later that year and in the early months of 1909, an embellished feature from Harper’s Weekly about William Bonney, titled “A Notorious Outlaw,” was reprinted in newspapers throughout New Jersey, Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, Nebraska, Tennessee, North Dakota, West Virginia, Montana, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, Kentucky, Virginia, Florida, Minnesota, California and other states across the country. “Fearless Billy the Kid, who reveled in carnage,” the article declared. “Only a boy, yet a terror.”

In 1911, two different articles titled “Killing of Billy the Kid” were published in newspapers in Canada and Australia. Two years later, an article about William Bonney titled “Billy the Kid: The Most Famous of the Bad-Men of the West,” written by author Frank J. Arkins was published in New York, Pennsylvania and more than a dozen other states across America. “The Kid killed more men, wantonly and for sheer love of murder, than any other man of whom there is a record in the west,” Arkins sensationally declared. A dose of “Billy fever” struck Australia in 1914, as dozens of newspapers across the land down under published various articles about the American desperado.

By 1915, “Billy the Kid” was the name of a racehorse bolting toward finishing lines in various states in America, and was also the name of a popular young monkey at a zoo in Kansas. Numerous articles about William Bonney’s exploits continued to be published in newspapers across the country before Charles A. Siringo’s A History of Billy the Kid was released in 1920. Siringo’s independently published book received a recommendation in the Boston Globe but failed to make a dent outside New Mexico, although a summation of William H. Bonney’s life under the headline “Made Name As Desperado” was published in various states. In 1921, the story of Billy Bonney’s capture at Stinking Spring based on the recollections of Garrett posse member Jim East was published by the Boston Globe and other newspapers across the country.

While William Bonney was mentioned sparingly in a variety of articles in 1922, the Kid was back with a bang the following year in a feature titled “Back-trailing on the Old Frontiers: Billy the Kid, Chief Figure in Border Warfare in New Mexico, a Bad Man of Pioneer Days.” The article about Bonney’s life and Charles M. Russell’s drawing titled Billy the Kid Avenges the Death of John Henry Tunstall, was published by newspapers in New York, California and numerous states between them. Later that year, “The True Story of the Killing of Billy the Kid,” as told by John W. Poe, was published across the pond in World Wide magazine in London, England, and reproduced in almost every newspaper in Montana.

People in California were able to read another article about William Bonney published across the pond by World Wide magazine when the Los Angeles Evening Post-Record reproduced E.A. Brininstool’s lengthy piece, “Billy the Kid,” which provided recollections from John W. Poe, in February 1924. The name “Billy the Kid” was also advertised in newspapers across America later that year when inviting the population to visit their local movie theater.

BILLY ON THE BIG SCREEN

The art of filmmaking was still in its infancy when a silent film titled Billy the Kid was released in 1911. Written by Edward J. Montagne and directed by Laurence Trimble for Vitagraph Studios, the film starred Edith Storey—who had recently played the lead in a film adaption of Oliver Twist—in the role of Billy the Kid. The plot revolved around an orphaned young girl raised to become a cowboy by her grandfather, “Uncle Billy,” who is kept unaware of the child’s gender. The 16-year-old “Billy the Kid” is kidnapped by a gang of outlaws on her way to school and held for ransom. Her grandfather, the sheriff, rushes off to rescue her with his foreman, Lee Curtis, but Billy the Kid manages to escape. The Kid informs her grandfather that she wants to be “Billy the Kid,” and live her life as his foreman Lee Curtis’s companion. “Uncle Billy” remains silent, and the teenage girl soon changes her name to Mrs. Lee Curtis.

To say the silent film Billy the Kid was even loosely based on the life of William Bonney would be an overstatement, but the comedy-drama Western was received warmly by the paying public. The picture played in movie theaters throughout the United States, the United Kingdom and Australia. “One film worth going a long way to see is Billy the Kid,” the Geelong Advertiser declared in Victoria, Australia, on January 6, 1912. The one-reel film described as a “Yankee Comedy” when advertised in Newcastle, England, has since been lost to history.

While Joseph Santley and Walter Woods’s play kept live audiences entertained, it took more than a decade for any kind of Billy the Kid to once again ride across the silver screen. Contrary to popular belief, King Vidor’s movie based on Walter Noble Burns’s book starring Johnny Mack Brown was not the next Kid film enjoyed by the public. In late 1924, film producer Jesse J. Goldburg’s motion picture Billy the Kid, starring Franklyn Farmer in the lead role, was released in cinemas. The film continued playing in movie theaters in California, New York, New Jersey, Indiana, Texas, Kentucky, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Louisiana, Maryland, Iowa, Alabama, and other states throughout 1925—the same year Harvey Fergusson publicly suggested the Kid had been forgotten.

Jesse J. Goldburg’s film, written and directed by J.P. McGowen, received praise in various newspapers following its release. “Billy the Kid is a wow,” proclaimed the Appeal-Democrat in Marysville, California, on January 18, 1925. “It has fast action, good comedy and a fine love story.” The Lebanon Daily News in Pennsylvania happily provided a summary of the film’s plot for readers:

[Franklyn] Farnum plays the parts of Billy the Kid, the supposed bad man and Tom Price, young ranch owner who is being hounded by the village scoundrel. Point is that these two so closely resemble each other scarcely anyone can tell them apart, and when Tom is led off to prison, Billy steps in and pretends he is Tom in order to get from the invalided widow Price the information as to where the stolen booty is hidden. The problems that develop from this situation add delight and pleasure to every foot of the film.

Leading man Franklyn Farnum was supported on screen by the beautiful Ethel Shannon. “As Tom Price’s sister, she is demure and charming and immediately wins the sympathy of every audience,” the Call-Leader declared in Indiana in February 1925. “Billy the Kid, the New Mexico outlaw who made history for the southwest in the early eighties, is at [the Ideal Theater], with Franklyn Farnum as the star,” the Albuquerque Journal announced in New Mexico on December 12, 1925.

Jesse J. Goldburg’s Billy the Kid was still playing in cinemas across the States when Walter Noble Burns’s The Saga of Billy the Kid was published by Doubleday Page & Co in New York in early 1926. The delightfully written and frequently embellished book became a hit, with excerpts and accompanying artwork published in newspapers across the country. After years of publicity in theatrical productions, articles and motion pictures, the household name Billy the Kid finally had an author with the literary talent worthy of his story. “It was Burns’ Billy, the young outlaw who fought for his friend Tunstall, who was offered a pardon that never came, who loved the sister of a powerful ranchman, who was shot down in the dark at the age of twenty-one,” says historian and author Mark Lee Gardner. “It was this Billy, the real-life Kid, that became a cultural icon.”

Walter Noble Burns may not have saved Billy the Kid from cultural irrelevance in 1926, but what the author did do was steer the masses in the direction of the real history rather than entirely fictionalized depictions of the famous outlaw. That alone was a significant contribution to American West history and pop-culture for which we should all be thankful and serves as the talented writer and researcher’s true legacy.