Catherine and the Kid

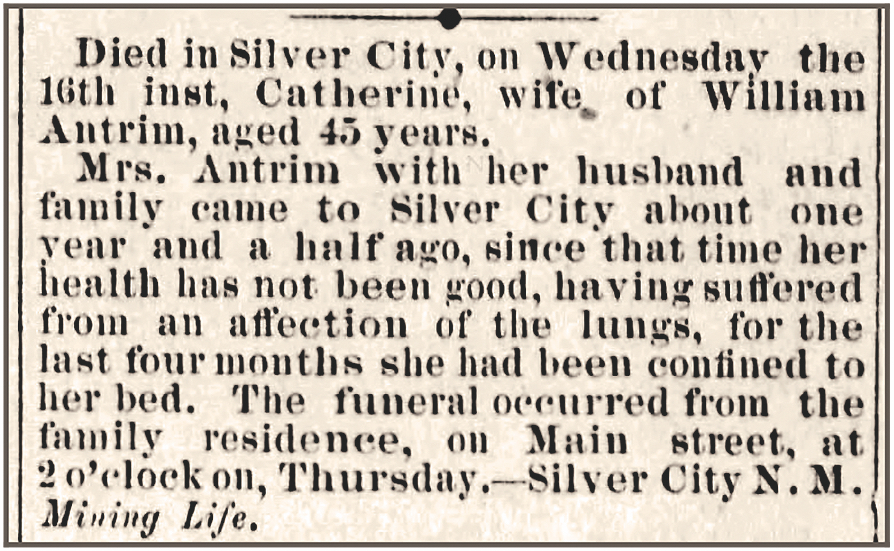

She was known in Kansas as “The Widow McCarty” and a resident in Silver City, New Mexico, described her as “a jolly Irish lady, full of life, fun and mischief, [who] could dance

the Highland Fling as well as the best of dancers.” Journalist Ash Upson described Catherine as “about medium height, straight and graceful in form, with regular features, light blue eyes, and luxuriant golden hair. She was not a beauty, but what the world calls a fine-looking woman.” And then he adds, “Her charity and goodness of heart were proverbial.”

It’s safe to say, young Henry, and his younger brother, Josie, lost a much-needed influence, at a much-needed point of their lives.

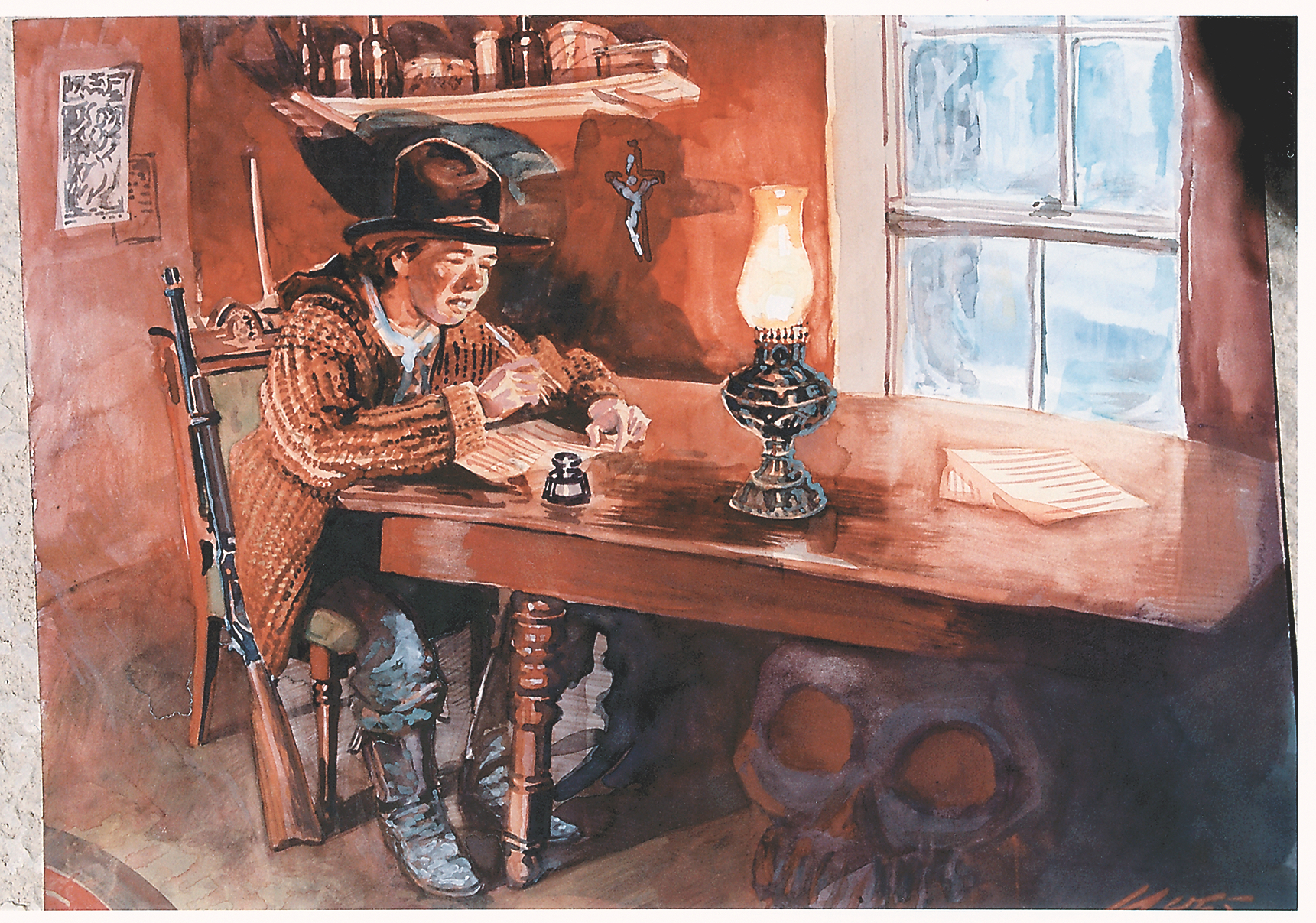

All Illustrations by Bob Boze Bell

I’m not driving to Utica, New York, to start this Renegade Roads trip—or anywhere else Billy the Kid was supposedly born that isn’t within the New Mexico boundaries.

Utica is the latest potential birthplace—following New York City (the most commonly cited) and, in no particular order, Indiana, Kansas, Ireland, Ohio, Missouri—and there’s a lot of evidence to back up that Utica claim. But it’s still just circumstantial.

I’m starting in New Mexico, because that’s where his legend was born. And, yeah, you can even find some theorists who say the Kid was born here, too.

The first stop is First Presbyterian Church in Santa Fe, and not because it’s just a 23-minute drive from where I live and write or because my son was baptized there 23 years ago.

The church was organized on January 6, 1867; the ruins of a failed Baptist church and two acres were bought two months later; and on March 1, 1873, the widow Catherine McCarty married William Antrim in the church. Her two sons, Billy and Joseph, were witnesses. The family briefly moved into the Exchange Hotel.

The City Different

While the current First Presbyterian Church is located on the same property as the original, the Exchange Hotel was torn down in 1919 and replaced with La Fonda on the Plaza in 1922. Three years later, the hotel became one of Fred Harvey’s Harvey Houses, and today, just off the Santa Fe Plaza, remains a popular hangout for tourists and locals—and walking distance to the New Mexico History Museum, Palace of the Governors, Loretto Chapel, The Cathedral Basilica of St. Francis of Assisi and O’Farrell Hat Company, where hatmaker Scott O’Farrell is always asking me to bring Bob Boze Bell for a visit to talk history and hats.

The Antrims didn’t stay long in Santa Fe, but Billy would return years later, writing unanswered letters to Governor Lew Wallace while waiting in jail before being sent south to Mesilla (Gadsden Museum), near Las Cruces (New Mexico Farm and Ranch Heritage Museum), to be tried for the murder of Sheriff William Brady. The Santa Fe jail is now site of Collected Works Bookstore & Coffeehouse.

The Antrims went south, first stopping in Georgetown, which at its peak had a population of 1,200, but now has a historic cemetery, some vacation cabins and a lot of gorgeous mountains. In 1873, Georgetown suited William Antrim but not Catherine, so they moved to Silver City (Silver City Museum, historic Fort Bayard).

Silver City Days

Young Billy thrived at his new home, becoming a good student at the public school and performing in amateur theater. His mother took in boarders and sold homemade pies and sweetcakes to help make ends meet, while his stepfather prospected in the area, worked as a butcher and carpenter and gambled.

And young Henry (called that to avoid confusion with stepdad William) might have grown up to be a forgotten productive member of society if Catherine hadn’t died of consumption on September 16, 1874. With his stepdad having no interest in parenting, Billy fell in with bad company.

That led to the straying youth’s arrest for stealing clothes from a Chinese laundry. The sheriff locked him up in Silver City’s new jail, hoping to scare the kid away from a life of crime, but Billy escaped through the chimney and fled to Arizona.

And there begins the Kid’s missing years until he shot and killed a bully named Frank P. Cahill, who had pinned the Kid down and was slapping him, at Arizona Territory’s Camp Grant on August 18, 1877. Once again, Billy disappeared, only to show up a few months later in New Mexico’s Lincoln County.

Frank B. Coe said “the Kid,” as he was called, worked on Coe’s ranch and “was very handy in camp, a good cook and good-natured and jolly.” He was also an excellent shot.

By November, the Kid was working for transplanted Englishman John Henry Tunstall, who had started a ranch in Lincoln County, started a store in Lincoln, the county seat, and, while he might not have realized it, started a deadly war against a powerful faction known as the House.

A Country for Bold Men

The Lincoln County War is far too complicated to detail in a travel article (read Frederick Nolan’s myriad nonfiction books), but Lincoln today does a fine job of explaining things since the whole village is a historic site—and little has changed in its appearance more than a century later.

Tunstall was murdered on February 18, 1878—a crime witnessed by the Kid—in what is now part of Lincoln National Forest, where a “sweet, gentle mare” named Honey tried to murder me while riding to the site years ago. In 1878, a series of retaliatory shootings followed, including the ambush murder of Lincoln County Sheriff William Brady, before the Lincoln County War arguably ended with a fiery, deadly gunfight in the town that left several dead.

But Not the Kid

In short order, Wallace took over as territorial governor with a promise to end Lincoln County’s troubles, but he was preoccupied with getting a better job—an ambassadorship to the Middle East. Wallace made a deal with the Kid: Testify in a military court of inquiry at Fort Stanton (Fort Stanton Historic Site) and “go scot free with a pardon in your pocket for all your misdeeds.”

Billy lived up to his end of the bargain. Wallace didn’t. So the betrayed Billy rode off for a new chapter in his life.

Viva Billy

Which was mostly gambling in Las Vegas (City of Las Vegas Museum), Anton Chico, Puerto de Luna (Our Lady of Refuge Church) and Fort Sumner.

By 1880, the Kid, rustling with some pals, became an annoyance to Wallace and newly elected Lincoln County Sheriff Pat Garrett, who ambushed the Kid and his pals at Fort Sumner and captured Billy at Stinking Springs (on private property). Billy was taken to Las Vegas and then by train to Santa Fe before heading to Mesilla (Gadsden Museum), where he was tried for Brady’s murder, found guilty and sentenced to be hanged in Lincoln.

But the Kid escaped in Lincoln, killing two deputies, and riding out of town unmolested—till Garrett shot the Kid dead in Pete Maxwell’s bedroom back in Fort Sumner on July 14, 1881.

Johnny D. Boggs also recommends Michael Wallis’s Billy the Kid: The Endless Ride, Mark Lee Gardner’s To Hell on a Fast Horse: The Untold Story of Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett and Bob Boze Bell’s The Illustrated Life and Times of Billy the Kid.

A WIDE SPOT IN THE ROAD

BOSQUE REDONDO MEMORIAL AT FORT SUMNER HISTORIC SITE

Fort Sumner is home to the Billy the Kid museums and the graves of Billy and his “pals” Charlie Bowdre and Tom Folliard aka Folliard. We’re not going to pick a favorite, but the museum not to be missed is the Bosque Redondo Memorial at Fort Sumner Historic Site.

Created in 2005, this state-of-the-art and incredibly moving museum, designed by Navajo architect David Sloan, powerfully documents the 1863–68 internment of Diné (Navajo) and Ndé (Mescalero Apache) people on the Bosque Redondo Indian Reservation that left an estimated 1,500 Native dead from starvation, disease and exposure. The subject is heartbreaking, but the memorial also celebrates the perseverance and triumphs of the tribes today.

nmhistoricsites.org/bosque-redondo

GOOD EATS & SLEEPS

GOOD GRUB: Santa Fe Bite, Santa Fe, New Mexico; Little Teacup Brewery & Distillery, Fort Sumner, New Mexico; Charlie’s Spic & Span, Las Vegas, New Mexico

GOOD LODGING: Inn of the Governors, Santa Fe, New Mexico; Wortley Hotel, Lincoln, New Mexico; Hotel Encanto de Las Cruces, Las Cruces, New Mexico