Peg Leg Smith, ranks right up there with America’s legendary mountain men, including Bill Williams, Jim Bridger, Kit Carson, Joe Walker, Jed Smith and Tom Fitzpatrick. He explored and trapped with all the great ones but unfortunately, there are no photos of him.

He was also one of the Old West’s grittiest mountain men. A fierce, ask-no-quarter, give-no-quarter, fighter. He could let out a blood-curdling war cry that was the envy of any Comanche warrior. He also had a rascally career one of the Old West’s greatest horse thieves.

Smith was another of those storied Scots-Irishmen on the American frontier. He began his career as a mountain man when he left Missouri in 1820 with Antoine Robidoux on a two-year trapping and trading expedition among the Sioux and Osage Indians. Then, in 1824, he went to New Mexico as a free trapper. In the fall of 1826 he joined storied trapper Ewing Young’s expedition into today’s Arizona. He spent a good part of his life trapping the rivers of the Southwest.

Since the area was still a part of Mexico and the government in Mexican capital changed frequently, the American trappers never knew when a new government would render their licenses null and void. Many trapping parties had their season’s cache of furs confiscated by a new governor in Santa Fe. The trappers circumvented the situation by making their rendezvous point in Taos. From there they would smuggle their furs north to the American border at Bent’s Fort on the Arkansas River.

The Gila River and its tributaries was home to several Apache groups making it one of the most dangerous places in the West for the fur trappers. One season only sixteen out or one hundred and sixty trappers survived.

It was in the fall 1827 in North Park, Colorado that Smith was wounded in the left leg during a battle with Indians. With the help of Milton Sublette and a jug of “Taos Lightning,” a concoction strong enough to peal the hide off a gila monster, the two trappers amputated his leg. Smith himself cut through the flesh, and then Sublette sawed through then the bone. The wound was then seared with a rifle barrel heated in in hot coals until it was red-hot.

He was taken in by the Ute Indians and miraculously recovered from his ordeal by a woman who chewed roots and berries into a concoction then she spit the juice on his wound. That winter he whittled himself a new leg and gained a nickname.

The left side of his saddle was fitted with a long pouch instead of a stirrup, to receive the stump. It was said that when he got into a barroom brawl, he could unhook his wooden leg in an instant and use it as a shillelagh. He became known as the nastiest barroom fighter in the West.

He arrived in California in early 1829 and stole a herd of horses, driving them to the mountains of New Mexico where they were sold at a handsome profit. He partnered up with another famous mountain man, Jim Beckwourth and a Ute Indian chief named Walkara trapping and stealing horses. In 1839 he and Walkara managed to rustle 3,000 horses from the poorly guarded California ranches.

The fur trade was on the wane by 1840. The beaver were almost extinct, silk became the new fashion and the trappers had to find another line of work. Many took jobs as scouts for the Army and others became guides for the emigrant wagon trains heading west to Oregon and California or opened trading posts.

During the late 1840s Smith was operating a trading post on the Oregon Trail helping emigrants on their way West. They described him as a “jolly one-legged man.”

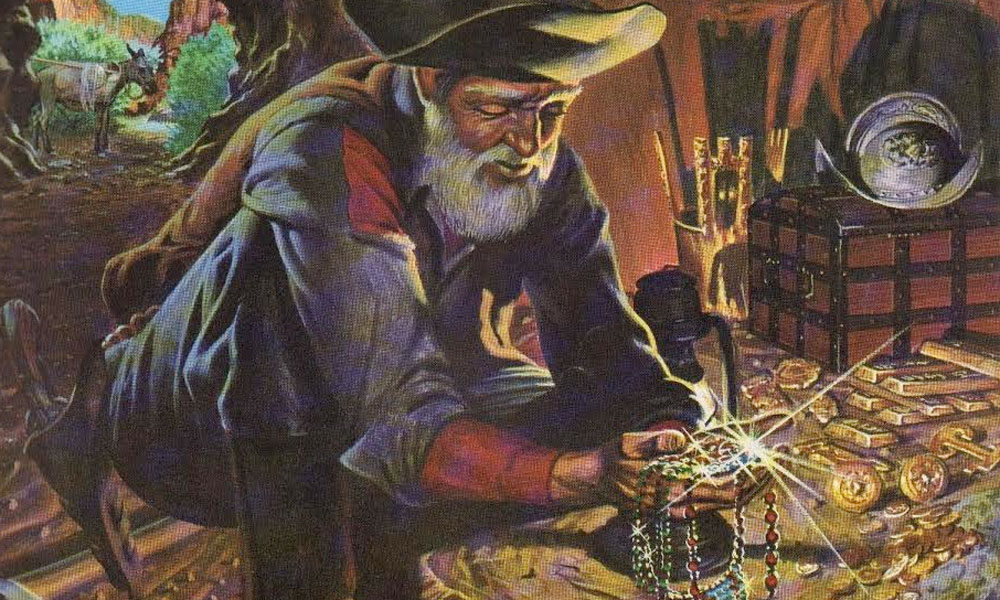

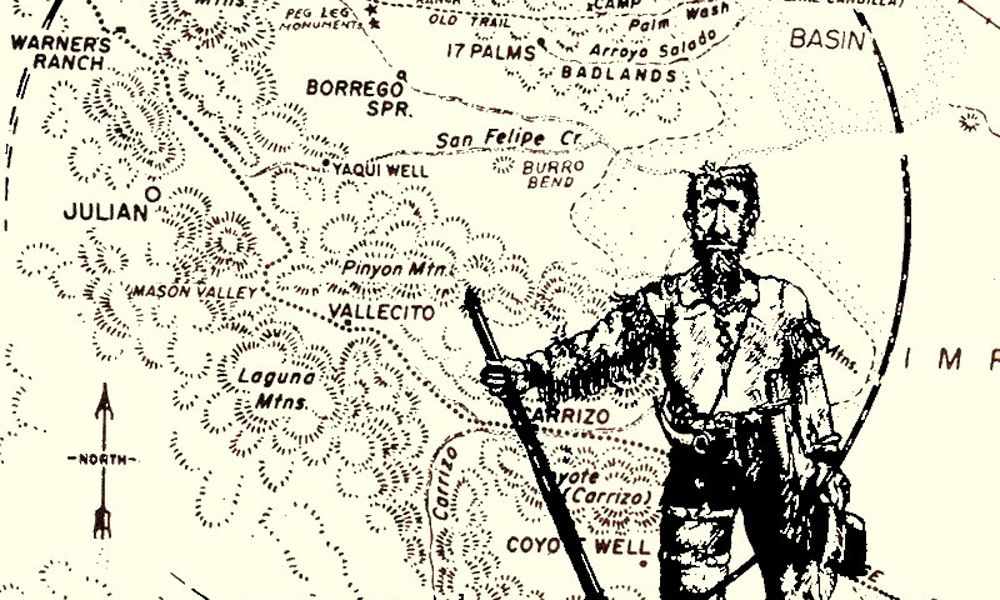

Peg Leg Smith’s greatest claim to fame was the gold mine he found then lost. In 1829, while traveling from Yuma on the Colorado River to Los Angeles, he located the gold at Borrego Springs near today’s Palm Springs. Smith had attempted a shortcut across the desert but lost his way and to regain his bearings he climbed a precipitous hill. While reconnoitering the area, he noticed some lumps of black, burned-looking ore thickly sprinkled with yellow particles of varying size, which veritably covered the entire hill.

Attracted by the curious appearance of the rock he gathered up a few samples and carried them to Los Angeles where an expert pronounced the particles pure gold.

Smith was never able to relocate his golden hill and over the next fifty years, many searched in vain for what had become the Lost Peg Leg Mine. He traded tall tales for liquor and went off to the desert at least three times to guide gullible gold seekers to his legendary mine. He would usually run out on them about the same time the liquor ran out.

A Mexican vaquero reportedly found the burned black specimens that characterized the gold from the lost mine. Thereafter when his funds ran low, he would disappear for a few days and return, his pockets full of gold nuggets. The vaquero’s secret died with him a few years later.

The Lost Peg Leg was found and lost a third time when a miner, cutting across country accidentally climbed the same hill as Smith had years earlier and found he was standing on a hill laden with gold. Filling his saddlebags he continued on to Los Angeles where he fell sick and died, leaving a small fortune to the doctor who attended him. However, the whereabouts of the marvelous hill of gold remains a riddle to this day.