Shavetail

The 17th century term “Lingo” was rooted in lingua, Latin for “tongue.” One of its definitions—“the vocabulary of a special subject or jargon of a class of persons”—seems especially apropos for many groups of Westerners. Cowboys especially had a knack for colorful banter that often found its way into everyday language.

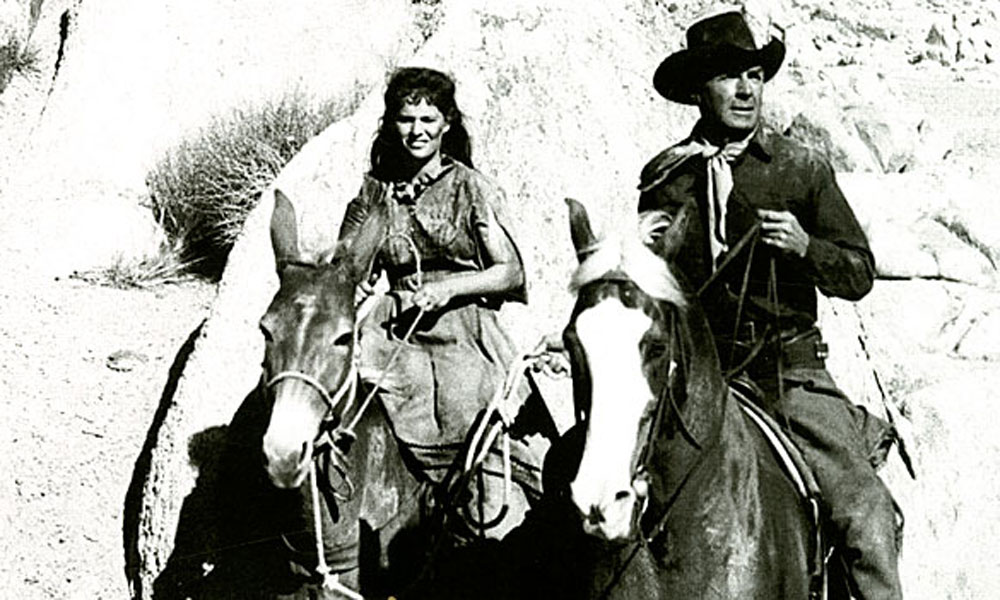

As just one of a litany of examples “shavetail” comes to mind. Win Blevins tells us in his Dictionary of the American West that the word referred to “A broke horse in contrast to the broomtails, wild range horses….” The idea was that once a horse had been broken, “it was customary to pluck the tails… to make them easy to distinguish from unbroken critters.”

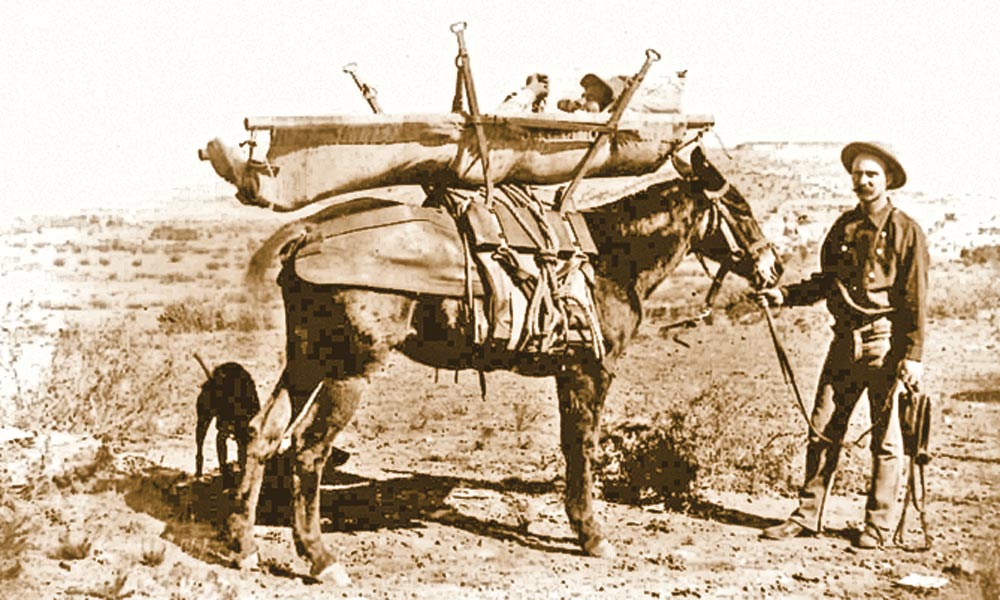

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Frontier soldiers placed their own spin on the matter. To troopers a shavetail was a new mule that hadn’t been trained to respond to bell commands. Educated, giant-eared, beasts of burden were said to be “bell sharp” while their neophyte four-legged brethren had their tails shaved until they had learned the ropes, although the air might turn blue when a muleskinner, “celebrated for his stubbornness and creativity profanity” according to Blevins, met his match in an equally tenacious braying mule.

It didn’t take much of a stretch of the imagination for frontier army veterans to extend the meaning. Experienced troopers applied the appellation to green second lieutenants after being turned out from their cadet days at West Point. The fresh, wet behind the ears Military Academy graduates might have been long on book learning, but to seasoned soldiers these youngsters had much to learn before they could be real commanders. By World War I, when a single gold bar was adopted as the insignia of second lieutenants for the first time in 1917, another term entered the lexicon—“butter bar.”