A hidden assassin with a shotgun blasted Charles Lummis in the face and chest. He was bloodied, blown off his feet, and left to die in the doorway of a one-room adobe, but Lummis was not bowed.

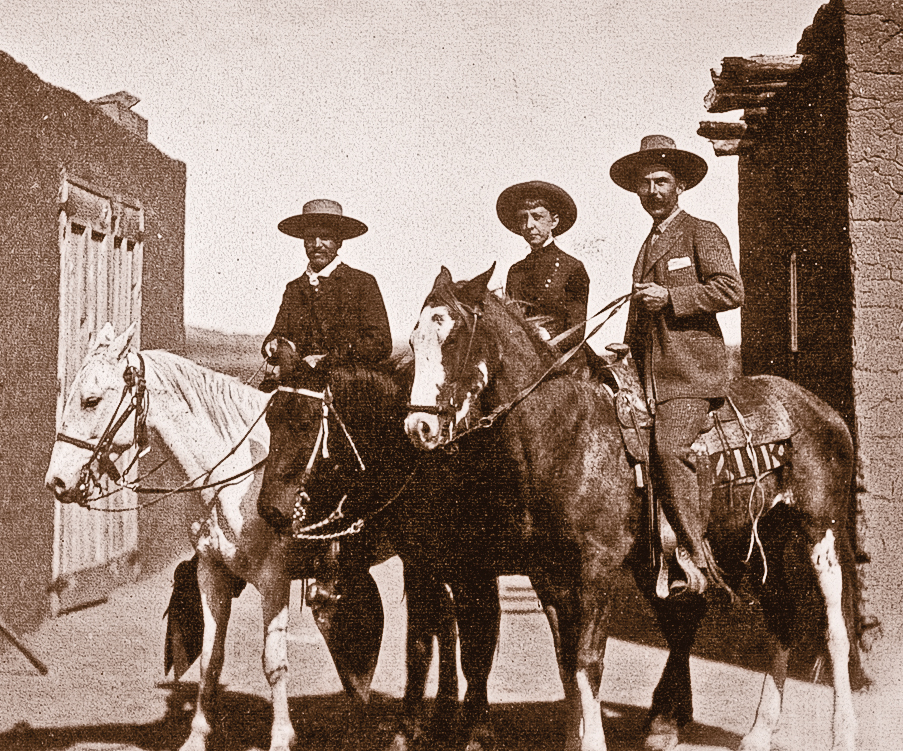

Pugnacious and convinced he was larger than life, Lummis possessed a journalist’s swagger and was a ready expert on most topics and people. But in the small Indian Pueblo of Isleta in the New Mexican Territory in 1889, that personality and a working box camera were enough to produce a $100 cash bounty for his execution.

He had seen too much and he sure as hell had said too much. Ironically, the reward was considerably more than he had ever been paid when his articles were published, but his investigative journalism had seared like a hot branding iron into the public reputation of a Gran Amo (“big boss”) in a prominent local clan and challenged the centuries-old local tradition of peonage and boss rule.

When the assassin fired, the reporter should have been killed instantly, like the five others previously marked to die, as the clans competed for political control of New Mexico’s Valencia County. When he was not slain, amazement became fearful whispering about Lummis being in league with the devil. Other failed assassination attempts against him only bolstered his legend across the Territory, where acts of God and el diablo were discussed as part of everyday life in the 1880s.

A better marksman would have made the kill with a lethal cloud of buckshot, a lacerated body left behind for burial. The failed delivery came from twin shotgun barrels at a range of less than twenty yards. The shooter’s false courage was mustered from surprise, cover of darkness and hiding behind the wall of a pigsty, kneeling in muck.

Writing later about the ambush, Lummis said, “Luckily it was an old burned-out muzzle loader and it scattered fearfully. [While] the door behind me was riddled with buckshot…” Only a few of the projectiles found their aim: his scalp, his hand, one hitting over his heart and another piercing his cheek, barely missing the teeth, but slicing into his throat and burrowing far back in his neck, where it remained for the rest of his life.

After he was spread-eagled on the ground, Lummis immediately jumped up, ran back into the house, bypassing a revolver for his single-barrel shotgun. He tore out into the bright moonlight of a bitterly cold St. Valentine’s Day, gasping hoarsely in a blind rage. He was searching for the man he saw—an extremely tall lone assailant with “unforgettable sloping shoulders.” Despite scouring darkened alleys and backstreets, he found no trace of the shooter.

He stemmed the flow of his blood with small blocks of ice made in pans nightly on a windowsill of a friend, who awoke, helped him back home and dragged his mattress up against the front door. Lummis laid there in pain with shotgun cocked, and waited for morning. His nocturnal chase was reconstructed the next day by Pueblo Indians who saw the trail of blood splatter dried on the sandy narrow streets.

In the hours before sunrise, ravaged by the messy brush with mortality. Lummis fingered the puncture wound in the flesh above his heart. The bullet’s trajectory had been blunted by a volume of verse, Birch Bark Poems. It was a book he’d written and printed years earlier, 2,500 miles to the east, and in another lifetime as a Harvard University undergraduate.

Lummis was born March 1, 1859, in Lynn, Massachusetts, and was left motherless at the age of two. He was known as “Charlie Bird” by his mother, Harriet (Fowler) Lummis, who died of tuberculosis at age 22, following the birth of daughter, Louise Elma. Probably for the last time in his life, Charlie was described as shy in spirit and sickly in bearing. The children were raised by their maternal grandparents in idyllic Bristol, New Hampshire; population 400.

It was there that his grandfather showed him some of their neighbors, now a company of newly enlisted local soldiers, assembling. They were marching off to the beginning of America’s Civil War. But for now, Judge Oscar Fowler prolonged the summer of Charlie’s childhood with an introduction to trout fishing. It became a lifelong love. He also taught Charlie the lesson that being small of stature did not mean yielding to others in life, and demonstrated how to effectively prevail from their mutual height of five feet, six inches.

He was homeschooled by his schoolmaster parent, Rev. Henry Lummis, in the classics of a European-style education, providing him with the foundation for acceptance by Harvard University. “I had no violent personal ambition for college,” Lummis wrote. “I went because Father had gone…and because it was the cultural convention of New England—to which I acceded as I did in most things. Up until Harvard.”

But it was the education he pursued outside the classroom during those seasons that formed the man he was to become. Lummis said he “studied reasonably for classes” and admitted his “escapades certainly brought [me] no credits”—but he called those adventures “the most important part of my college courses and of the most lasting benefit,” including “…milling with several hundred other boys, an experience of deep value to one who had been alone as much as I…” A chance campus encounter with one of those boys, a sophomore, would result in a lifelong friendship. Lummis had been warned by the upperclassmen in writing that his refusal to cut his hair short, as was the hazing tradition for entering freshman in 1877, would get him forcibly shorn. Lummis responded in writing as well, selecting a time and location where they could meet and “try” to cut his hair.

“Bully! It’s your hair,” encouraged the new student friend. “Keep it if you want to. Don’t let them haze you.” Even though he socialized with Harvard’s top families and was a scholar in his class, young Theodore Roosevelt recognized and liked the earned brashness of another like himself. Both had overcome illness and physical diminutiveness through exercise and perseverance.

Decades later when one had become the President and the other a Western writer living with American Indians, Lummis would have Roosevelt’s ear as part of an unofficial “cowboy Cabinet” and used his access to impact national policy, building on both men’s mutual love of the American West. The government’s attempt to “civilize” Arizona’s Hopi Indians drew the wrath of Lummis, who reported on having witnessed the suppression of their religious ceremonies, an order to forbid the use of indigenous language, herding native children at gunpoint to leave home and attend distant boarding schools, and forcing the young males to have their hair cut short, sometimes by sheep shears.

But in 1877, the focus was undergraduate tomfoolery. Charlie and his friends stole mercantile signs for dorm rooms, drank, smoked and dressed up as “professional vagabonds.” They practiced their begging and impersonation skills, landing in jail overnight until identified as Harvard students and tossed out in disgust that anyone would mock homeless poverty.

“From my cloistered life,” Lummis wrote irreverently, “I had come to the Tree of Forbidden Fruit. I had climbed that tree to the top.”

He challenged Mt. Washington with “sliding boards” (homemade skis), which were locally forbidden because several people had been killed on the steeper area of the slope, and deeply lacerated the soles of both of his feet on sharp rocks. Another youthful impulse found him on a trail topping New Hampshire’s Presidential Ridge in a sudden snowstorm. He was alone and dressed only in lightweight clothing. Trapped by descending darkness he caught his foot on a rock and fell face-forward. Reaching out to regain his footing, he felt—air. Tossing a rock ahead, he heard only a “faint click” several seconds later.

It was different danger that soon found Lummis—romance. It arrived, he said, in the form of “a pair of marvelous blue eyes and a wealth of golden hair,” belonging to Dorothea Roads, whom he tutored. Many years later, a found box of letters from Roads to Lummis would detail the story—which began when he was 21—of their young love, marriage, heartbreak and divorce.

Lummis dropped out from Harvard during his senior year, never graduating, and moved to Ohio to work on his father-in-law’s farm, leaving new bride Dorothea behind to complete her medical studies in 1880.

Lummis Goes West

A long and strange journey brought this New England intellectual to the racial and class turmoil of the American Southwest. The country was harsh; life was cheap.

Even more peculiar, Lummis had arrived out West on foot. He had left Cincinnati, Ohio, on September 12, 1884, where after farming, he worked as editor-in-chief for the Scioto Gazette. He then accepted an offer from the Los Angeles Daily Times to be city editor. “The printer’s ink was in my blood,” Lummis said.

Travelling in the wet and bitter cold of autumn and winter, the 26-year-old departed—dressed in low-cut street shoes, red knee-high stockings, knickers and a multi-pocket duck coat that could double as a water-resistant blanket—and “tramped” westward. His robust pace covered 30 to 40 miles daily and he took an indirect route of reportedly more than 2,000 miles in 143 days, arriving at his new job on February 1, 1885.

It was a time when travel across America was still measured by seasons, by skirmishes between indigenous people and new arrivals, and by weather changes that could leave life clinging from exposure on a nameless open horizon. Leaving the East for the Western frontier was more about the unknowns on the trail than the number of miles to the destination.

And yet Charles Lummis walked by himself, including crossing the peaks of the Rockies, having never visited the country before, and reported about his quest to readers in cities far away. He carried writing materials, matches, a small revolver (later changed for a .44), a hunting knife and a money belt with 300 “quarter eagle” coin dollars and fishing tackle.

Lummis filed weekly dispatches for the three-year-old Los Angeles Daily Times. He knew how to self-promote and sensationalize, and he changed his wardrobe along the way to a full traveling costume to fit his new image. He wore an ammunition belt, hunting knife, two Colt revolvers and, to the delight of children he encountered, even a stuffed coyote draped around his neck. He finished his custom corduroy outfit with a Navajo sash, a rattlesnake hatband for his sombrero and fringed buckskin leggings.

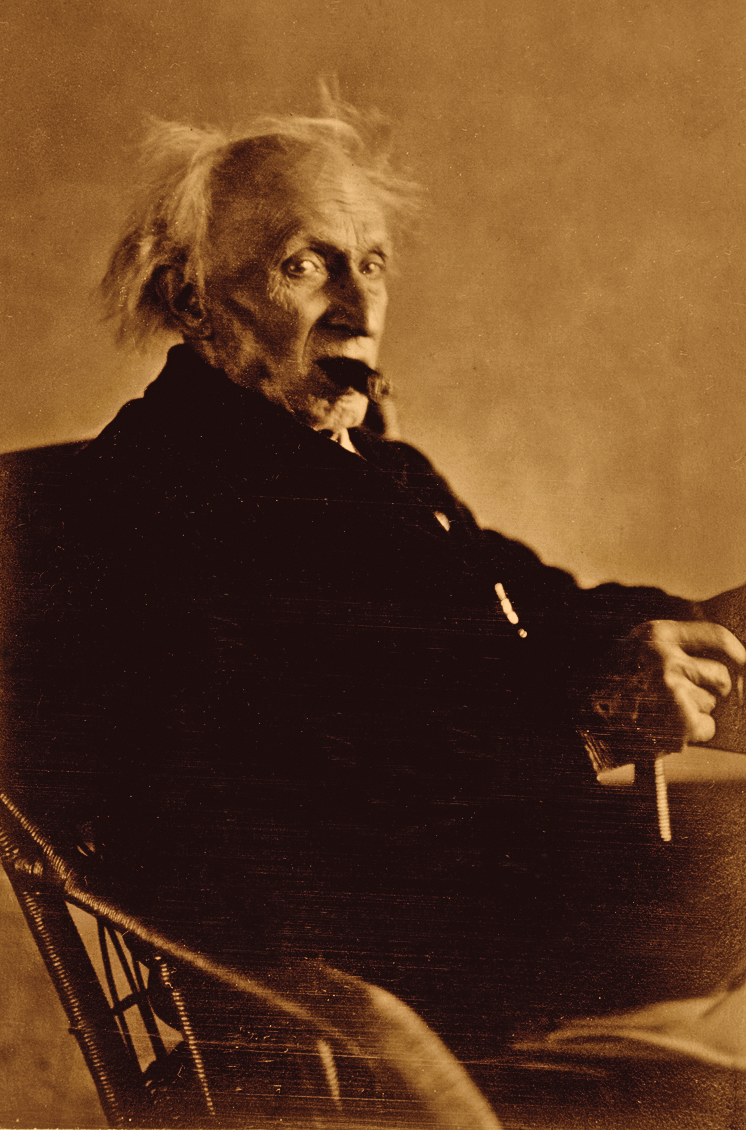

The transformation from Harvard Square to life west of the Rio Grande was complete. As he arrived in Los Angeles, now a literary star, he sported a new beard and well-chomped cigar. Times President and Publisher Col. Harrison Gray Otis said of Lummis’s appearance, “His garb was not reassuring to the timid,” and may have been “calculated to excite the curiosity of the police.”

Lummis’s series of articles became a national attraction, described as a “bonanza for newspapers.” One editor said Lummis’s articles “have a strange, indescribable interest and people have got to talking about ‘Lum’ all over the country. He is the most noted man in the West just now…”

Lummis presented readers a front-row seat to the scenery, adventure and rigors of solitary frontier travel. They were riveted by his interview with outlaw Frank James. The suspense of detailed serial reports from Fort Bowie, in Arizona Territory, captivated urban residents with America’s campaign to capture famed Chiricahua Apache leader Geronimo.

The chronicle of his journey and his own migration into America’s West would later be published in 1892, A Tramp Across the Continent.

What Lummis saw and what he wrote made him as popular as he was unpopular—all his stories were real, some were kept secret, and many were heartbreaking.

At General George Crook’s request, he did not write about the federal government’s forced transfer of Geronimo’s family and tribe members to Florida from Arizona in 1886.

Lummis did not report the throngs of white residents at the railway station cheering the exile of mostly old men and women and children as they boarded box cars. Crook thought any news coverage would incite other residents. Lummis watched the train depart down the track, as the reservation dogs howled and hopelessly pursued their owners. Some spectators used them for target practice and later left with the tribal horses.

Other secrets he chose not to keep.

Lummis published and photographed eyewitness accounts of his presence at an 1891 ceremony in New Mexico that was descended from Spain’s Los Hermanos Penitentes, the Penitent Brothers, three centuries earlier, which had now become a brutal re-enactment of Christ’s torture and crucifixion. The ceremony was introduced into the New World by the Catholic Franciscan friars with the Spanish conquistadors in 1594 as they crossed New Mexico. Lummis decried the 19th-century interpretation: “It shrank and grew deformed among the brave but isolated and ingrown people of this lonely land; until the monstrosity of the present fanaticism had devolved.”

The vivid descriptions and photographs of the secretive annual observance are disturbingly detailed in his book, The Land of Poco Tiempo (The Land of Pretty Soon), and were published in Scriber’s Magazine.

Lummis learned to take large-box photographs with five-by-eight-inch glass plates, carrying the forty-pound camera and dozens of pounds of the tripod and other equipment. He archived images of places and native peoples in their isolation before their absorption into modern society, like the shrouded Penitents ceremony and American Indian religious rituals. The prints numbered 10,000 between the years of 1888 and 1900 and, in quality and subject, rival other historical collections and later photographers.

In addition to writing and photography, Lummis admitted, women were his other interest and passion. His legendary womanizing was also his undoing.

He had three marriages, two divorces, and the questionable judgment of chronicling some 50 other women with whom he had liaisons. This fact made the newspapers when his second wife, Eve Douglas, offered it in evidence to the court in her request for a divorce. Some of his diary notations were coded/rated in ancient Greek, which he’d learned as a youth during his father’s efforts to make him more of a scholar than lothario.

According to Mark Thompson, a Lummis biographer who wrote American Character, The Curious Life of Charles F. Lummis, when he reviewed the collection of surviving Lummis diaries and materials at the University of California, and L.A.’s Southwest Museum, he even found found a legal defense on the subject of fidelity.

A Lummis lawyer had clarified, writing, “The more than 50 women with whom he allegedly engaged in illicit relations included no lewd women but many prominent and faultless ladies who consulted him as an authority in literature, history, and science.”

Thompson describes Lummis, as “…a drinker, probably a manic depressive and a womanizer,” but “a complex character who was a dynamo of energy and flamboyant to a fault. He had his hands in so many issues and trends of his day…”

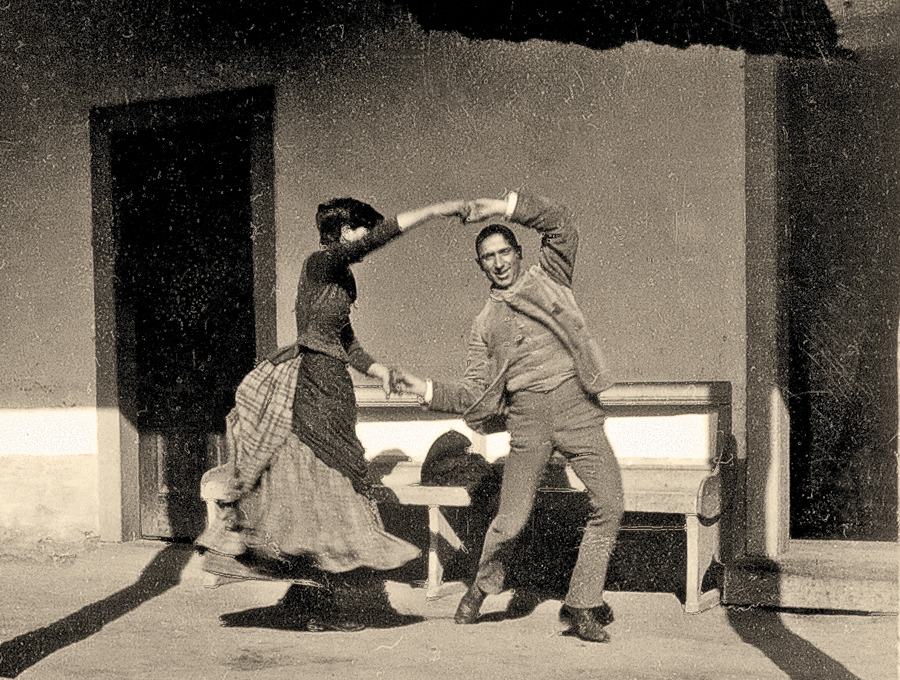

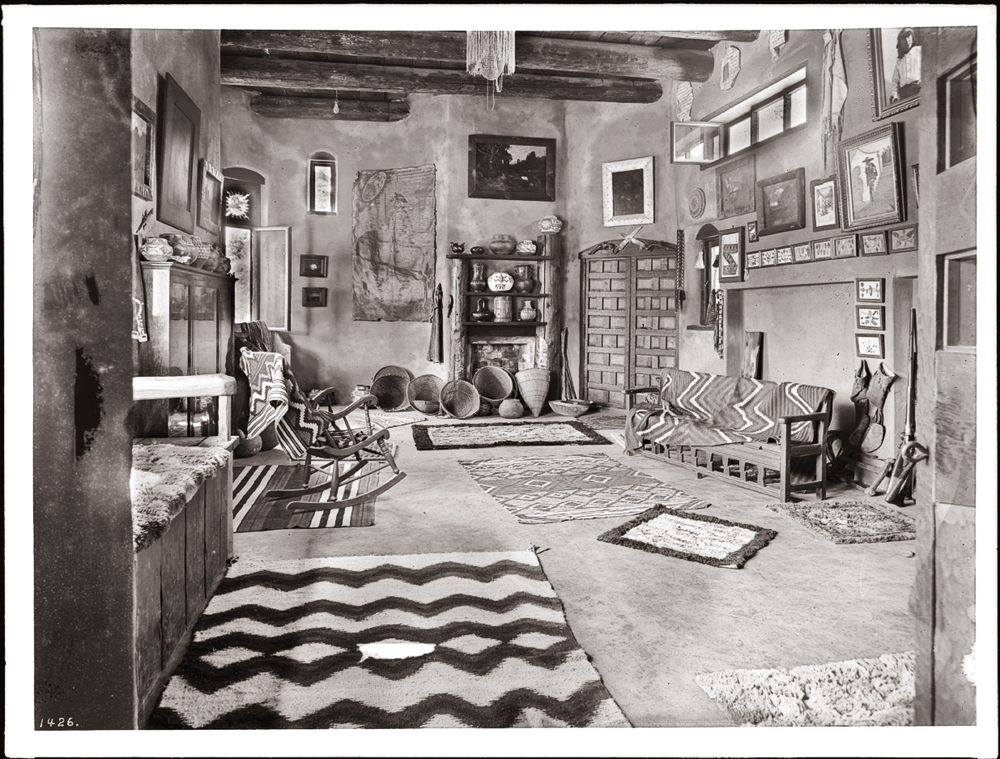

Lummis bought a small rural acreage in Los Angeles’ Arroyo Seco in 1895 and hand-built a remarkable stone estate he called El Alisal for the local sycamore trees. It took him nine years and the personal transport of countless arroyo stones with periodic help by friends from Pueblo Isleta.

It was here, in his later years, that Lummis consolidated his energies, his public issues agenda and his notoriety to impact regional and national attention. His home became the social destination for a wide range of prominent names of the day. Guests were treated with elaborate Spanish meals from traditional recipes, which Lummis also collected, and a resident troubadour who recanted traditional Spanish ballads and programmed entertainment into the early hours. Lummis appeared in self-styled period costuming to accentuate his visibility.

A Life Well Lived

Most historians agree on the enormous influence exerted by Charles Lummis in the late 19th and early 20th century. In addition to his prolific writing of at least 20 books and more than 500 columns when he was the editor of the monthly Out West magazine, he fiercely advocated for Native American rights and their cultural preservation. His inexhaustible efforts continued as a Southern California resident. He led the preservation and restoration of the chain of Spanish missions, the phonographic recording of nearly 550 traditional Spanish songs and a separate collection of 425 Indian songs from 37 languages. He established the Southwest Museum to archive the artifacts and history of his lifetime collection and was elected as the director of the city’s free library.

Lummis was an active member of many historical and scientific societies and was knighted by the King of Spain in 1915 for his preservation work of Spanish culture in North America.

Charles Lummis died of brain cancer on November 15, 1928, following the diagnosis a year earlier from a L.A. physician friend. He had already made arrangements for his wake wardrobe, funeral pyre and subsequent interment into a niche. His spot in the house wall was adjacent to the ashes of his beloved son, Amado, who at age six, died of pneumonia on Christmas Day, 1900.

The city of Los Angeles celebrates Lummis’s contributions to California at the Lummis Day Festival, now in its tenth year, each April, honoring his early efforts toward multi-culturalism.

Tom Augherton suggests reading American Character: The Curious Life of Charles Fletcher Lummis and the Rediscovery of the Southwest by Mark Thompson, winner of the 2002 Western Writers of America Spur Award in the biography category. Augherton is an Arizona freelance writer and was the first directly elected mayor in True West’s hometown of Cave Creek.