Alfred Jacob Miller, George Catlin, John Mix Stanley and Karl Bodmer’s romantic illustrations of America’s frontier Indians were matchless eyewitness portrayals until the advent of the camera.

Alfred Jacob Miller, George Catlin, John Mix Stanley and Karl Bodmer’s romantic illustrations of America’s frontier Indians were matchless eyewitness portrayals until the advent of the camera.

Thomas Easterly is credited as the first to photograph American Indians in the United States, in March 1847, when he took daguerreotypes of Chief Keokuk and other Sauk and Fox Indians who had traveled from present-day Kansas to St. Louis, Missouri.

Government expeditions and private enterprises in the 1850s produced our earliest photos of Indians in their frontier environs. Commissioned in 1857 by photographer John H. Fitzgibbon to paint Panorama of Kansas and the Indian Nations, artist Carl Wimar went on ambrotyping tours that captured images of Upper Missouri tribes. Doubling as the official photographer for the 1859 William F. Raynolds expedition of the Yellowstone region in Montana and Wyoming, topographer James Dempsey Hutton captured images of the Crow, Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes.

Since each daguerreotype could only be reproduced by making a camera copy of it, the technology progressed in the 1850s to a wet plate process that allowed for prints to be made from a negative. Within two decades, expedition and commercial cameramen had transformed the visual documentation of the frontier and brought its native peoples into American culture.

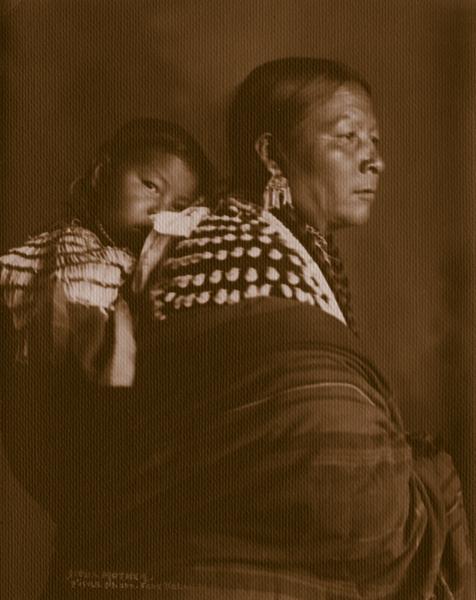

Although photos taken by outsiders present a perspective different than the Indian subjects’, they are still important in sharing the tribal historical record. As Laguna Pueblo writer Leslie Marmon Silko wrote in her 1981 book Storyteller, “The photographs are here because they are a part of many of the stories, and because many of the stories can be traced in these photographs.”

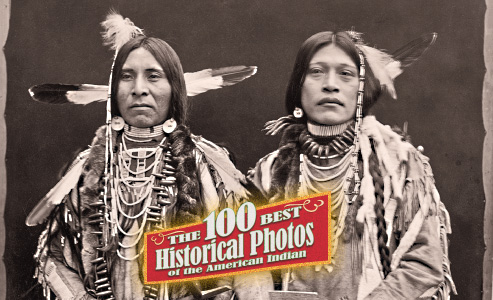

Among the treasures that stemmed from these pioneer efforts, we have chosen 100 of the best historical photographs of the American Indian. The journey has already started, with our Opening Shot, and continues throughout the magazine. Enjoy!

—The Editors

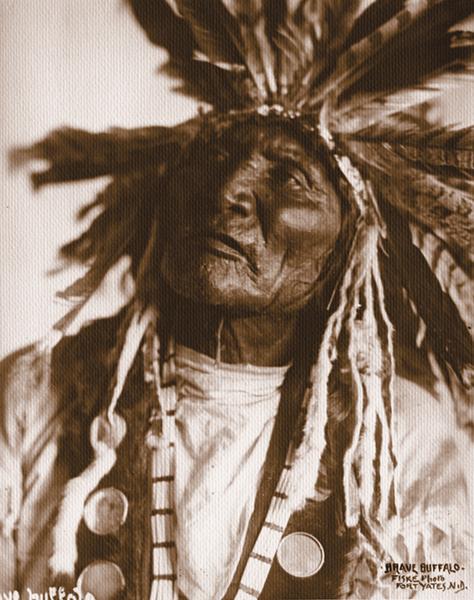

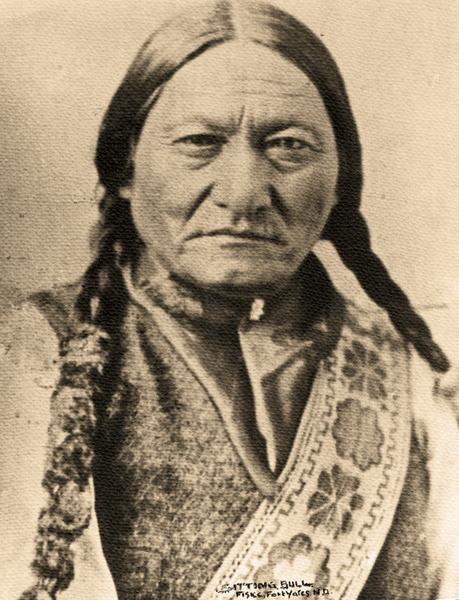

Frank Fiske’s Tamed Sioux

At the age of six, Frank Fiske experienced death. Along with his pals, he “blazed about the ‘dead house,’” he wrote, adding “Whenever the door was opened we would risk a ‘look’ and I can still recall the body as it lay upon a table while the post surgeons performed an autopsy to determine just who killed him.”

That body was Sitting Bull’s. Children at Fort Yates had been dismissed from school so they could see it in the morgue. Famous for leading his people in resistance against U.S. government policies, only to end up subdued on the Standing Rock Reservation in the Dakotas, the Lakota medicine man had been killed by Indian Police during an attempted arrest to dissuade Sitting Bull from joining the Ghost Dance movement.

Fiske’s father, the wagon master, witnessed Sitting Bull’s coffin lowered into the grave, heard “Retreat” sounded by the post buglers and then recorded in his notes: “With the end of Sitting Bull a permanent peace came to abide in the Sioux country and fighting became a lost art.”

The passage of only two weeks would prove him wrong. On December 29, 1890, Lakota followers who had been herded into a camp found themselves disarmed by 7th Cavalry troops. Somehow, during a scuffle with Black Coyote, his rifle fired; the military opened fire indiscriminately, killing men, women, children, even some of their own—about 150 Lakota and 25 soldiers died, with more dying later from their wounds.

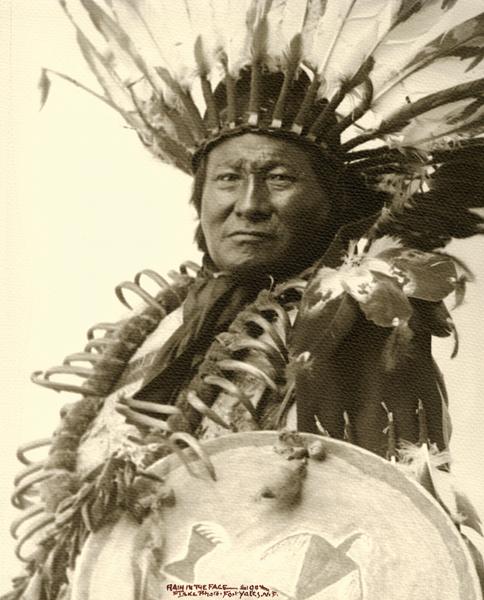

That year full of horrific carnage never left Fiske’s mind. He would grow up with Lakotas as his classmates, and he made them his subjects when he apprenticed under post photographer Stephen Fansler. When his master left in 1900, Fiske took over. When the post was abandoned three years later, Fiske continued to photograph the Sioux—Rain In The Face, White Bull, Mary Crawler. In all, he produced nearly 8,000 known photographs. He documented the Sioux as they were—often wearing a mixture of modern dress and traditional dress. His Indians celebrated weddings, graduations, birth ceremonies, cattle drives and rodeos. He didn’t re-create a tribal life that no longer existed, just the bare truth. Every wrinkle. Every bead. Every detail rich in life and color can be glimpsed in his period images.

Fiske lived most of his life among the Sioux in Fort Yates, dying a month after his 69th birthday. The State Historical Society of North Dakota preserves his collection of pioneer photographs.

Six Degrees of Separation: Sitting Bull Edition

Sitting Bull, the Lakota medicine man tragically shot dead by Indian Police at Standing Rock Reservation in the Dakotas in December 1890, was the uncle of White Bull, who contributed much to Stanley Vestal’s biography of Sitting Bull. Next to him is his brother, One Bull. The brothers joined forces with their uncle during the Battle of the Little Big Horn and fled with him to Canada before surrendering in North Dakota.

An outline of Frank Fiske’s photograph of Red Tomahawk is the symbol of the North Dakota Highway Patrol. Red Tomahawk went with the Indian Police to arrest Sitting Bull. After Lt. Henry Bullhead fired his revolver into Sitting Bull’s left side, Red Tomahawk allegedly shot the medicine man in the head.

Gall, one of Sitting Bull’s trusted lieutenants, spent nearly four years with the medicine man as an exile in Canada. But Gall and John Grass would split from the ranks, resigning themselves to reservation life. Sitting Bull was more defiant. When Gall signed his name to the Sioux Act passed in 1889, which gave away even more Sioux land, a disappointed Sitting Bull reportedly said, “There are no Indians left but me.”

C.S. Fly’s Geronimo

After roughly 30 years of raids in Mexico and the American Southwest, Geronimo surrendered, for the last time, that September. He and his people were imprisoned in Florida and, ultimately, in 1894, moved to Fort Sill, Oklahoma Territory. Geronimo never saw his homeland again. Before he reached his 80th birthday, he died of pneumonia at Fort Sill in 1909.

Photo Gallery

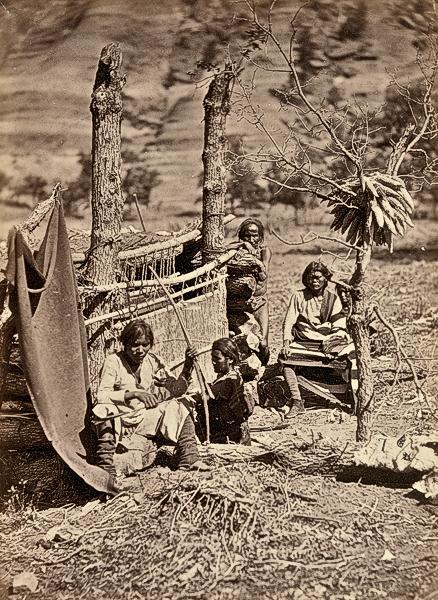

Timothy H. O’Sullivan captured some of the traditional daily life among the Navajo in this 1873 photo taken near Old Fort Defiance in New Mexico of Navajos clustered around a loom, hunting equipment and drying maize.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

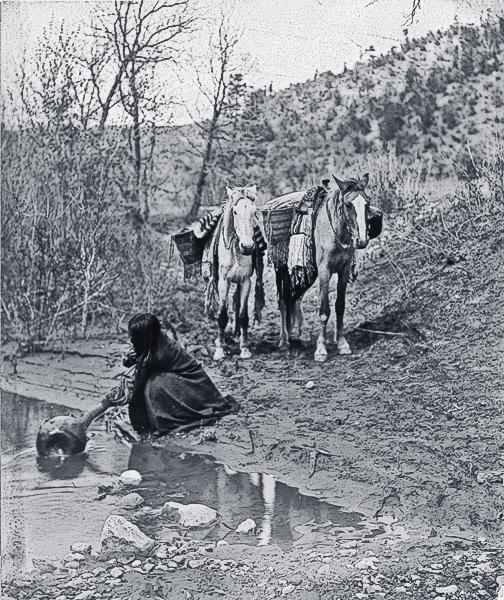

Apache women were skilled basket makers. Edward Curtis took this 1903 photograph of a woman filling her watertight basket with water to take back to camp.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

Edward S. Curtis photographed this Crow (Apsaroke) man, leaning back slightly, with strips of leather attached to his chest and tethered to a pole secured by rocks, participating in the piercing ritual of the Sun Dance that lasted at least four days; a dancer could not be freed until he experienced a vision.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

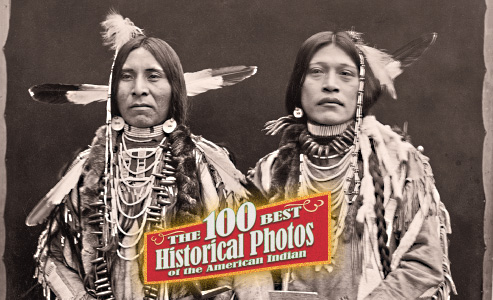

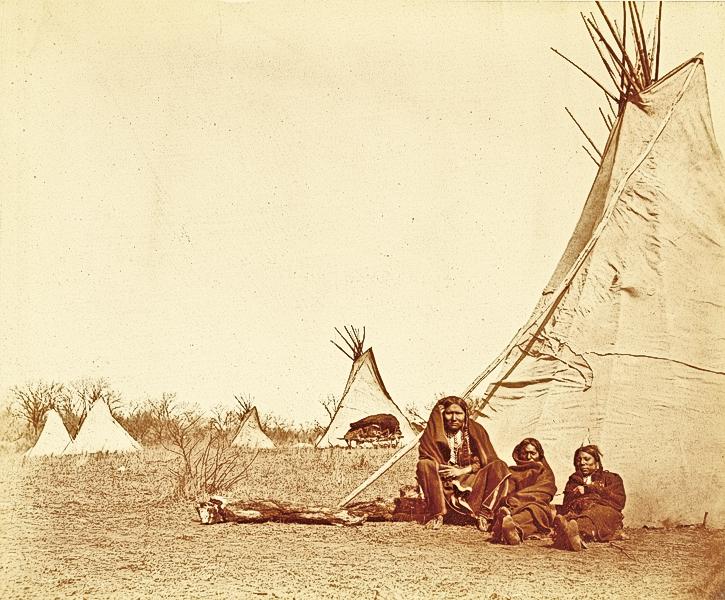

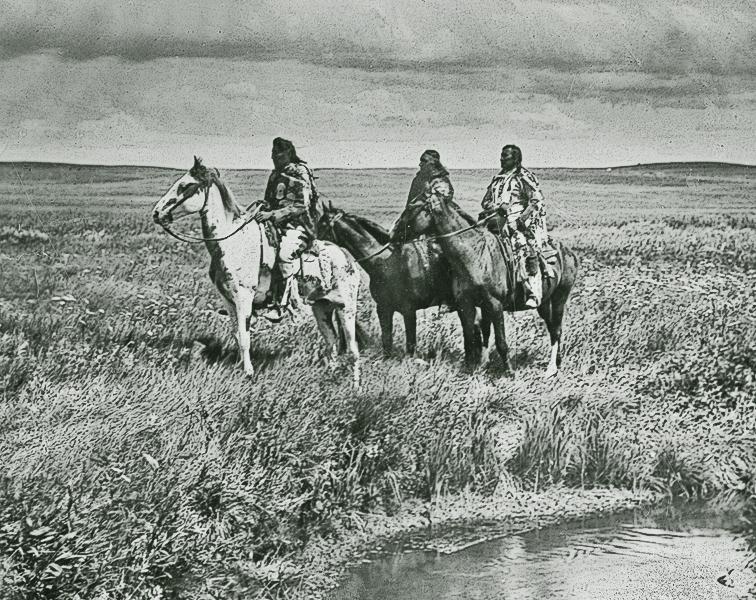

Taken by James Dempsey Hutton during William F. Raynolds’s 1859 expedition of the Yellowstone region, this photograph of Arapahos (including Warshinun, on the right) is among the early images that triggered the photographic trend to capture views of frontier Indians in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

– Courtesy National Anthropological Archives –

An Arikara medicine ceremony, performed as a prayer offering for rain and food, had been banned by the U.S. government since about 1885; photographer Edward S. Curtis arranged for some Arikaras to perform the outlawed ritual in 1908.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

After serving as field secretary to the governor during the Bannock War of 1878, Maj. Lee Moorhouse went on to become agent for Oregon’s Umatilla Indian Reservation in 1889. From 1888 to 1916, he produced more than 9,000 images of life in Umatilla County and the Columbia Basin, and he recorded on film these Bannock braves (from left) Jim Mukai and Ponga.

– True West archives –

– Frank Fiske photo; True West archives –

– Frank Fiske photo; True West archives –

Photographed in native dress during a Nez Perce delegation to Washington, D.C. in 1868, Chief Kalkalshuatash holds a feather fan and pipe. After meeting with the government to restore the provisions of an 1863 treaty, his people still fell victim to funds squandered by government officials.

– Courtesy Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology –

Terrequoip, known as Horse Back in English, was a Comanche chief of the Noconie band. Bleeding from his lungs confined the warrior to his camp, where William S. Soule captured this photo in 1873 at Wichita Agency near Oklahoma’s Fort Sill. His sickness moved him toward peace with the whites, and he urged his people to surrender to reservation life.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

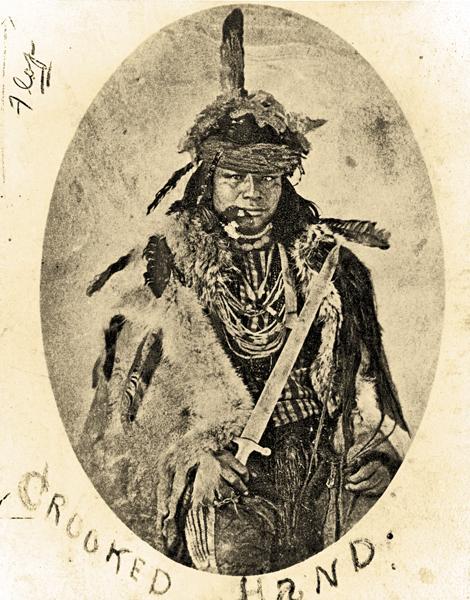

Despite a palsied hand, Crooked Hand, a Pawnee, gained notoriety as the “greatest warrior in the tribe,” anthropologist George Bird Grinnell reported. His son, Dog Chief, went on to serve as a U.S. Indian scout in the 1870s. This photo of Crooked Hand was taken circa 1870, three years before the warrior died.

– Courtesy Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology –

With a mixture of brains and other animal fats, this Dakota woman hand rubs the buffalo hide to help soften the leather so it could be made into robes, parfleches, moccasins and so on.

– Courtesy Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology –

In the Yuma tradition, young men courted sweethearts by playing the flute. Isaiah West Taber photographed this Yuma musician from Arizona in San Francisco, California, circa 1885.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Courtesy Robert G. MCCubbin Collection –

– True West Archives –

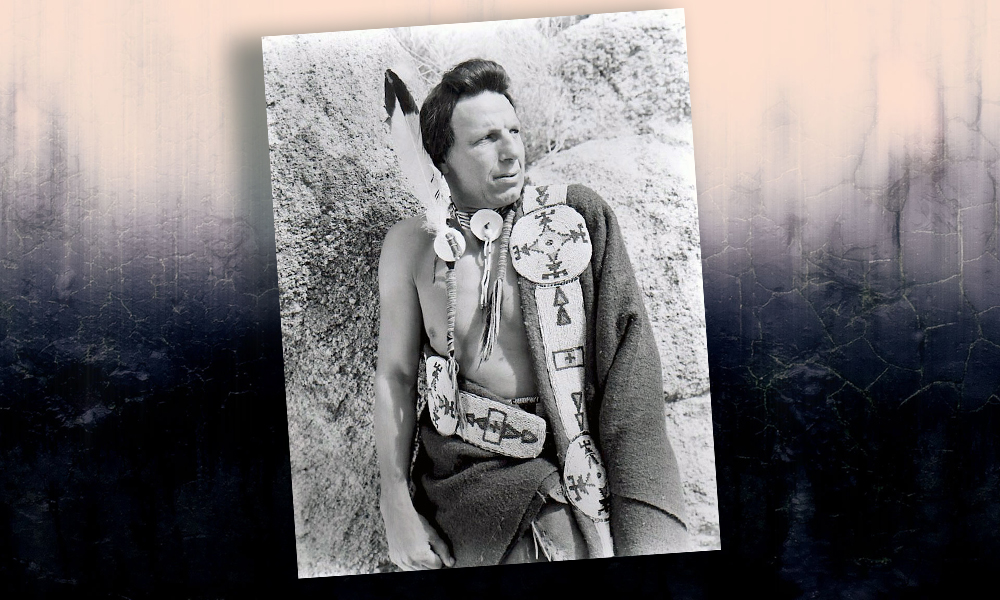

Geronimo, whom Gen. Nelson Miles named the Human Tiger, looks tamed and subdued in this photograph. A similar photo of him in painted headgear introduced his autobiography, published in 1906.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

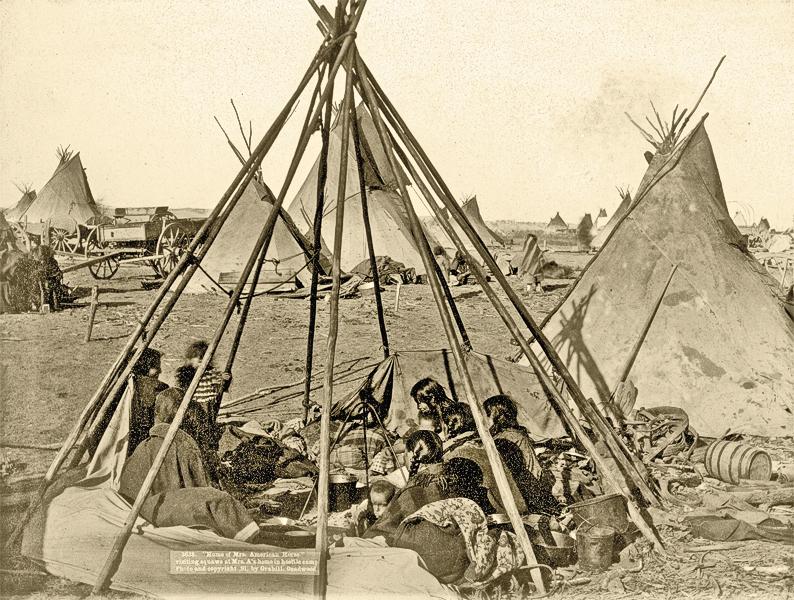

Oglala Lakota women and children sit inside the home of Mrs. American Horse, the wife of the Oglala chief who gained influence during the Great Sioux War of 1876-77, in this 1891 photo by John Grabill that was likely taken on or near the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

In northeastern Arizona, this kneeling Hopi woman combed and arranged the maiden’s hair into whorls, a coiffure that represented the squash flower and symbolized that a girl was of marriageable age.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –>/i>

Kiowa leader Hunting Horse stands with his daughters in this 1908 photograph by J.V. Dedrick of Taloga, Oklahoma. He served as a scout for Gen. George Custer, and he lived to be 107, dying in the same year, 1953, when this magazine was founded.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

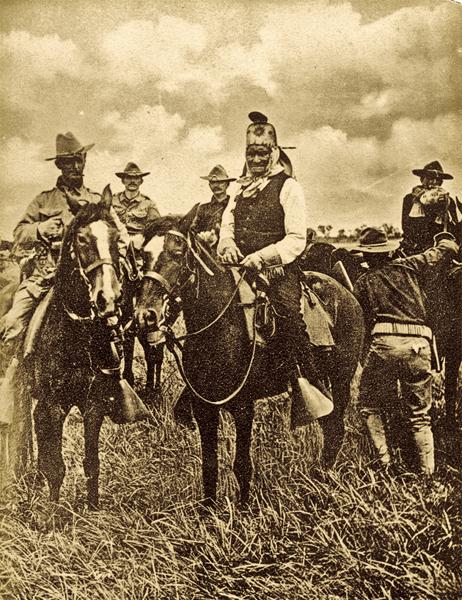

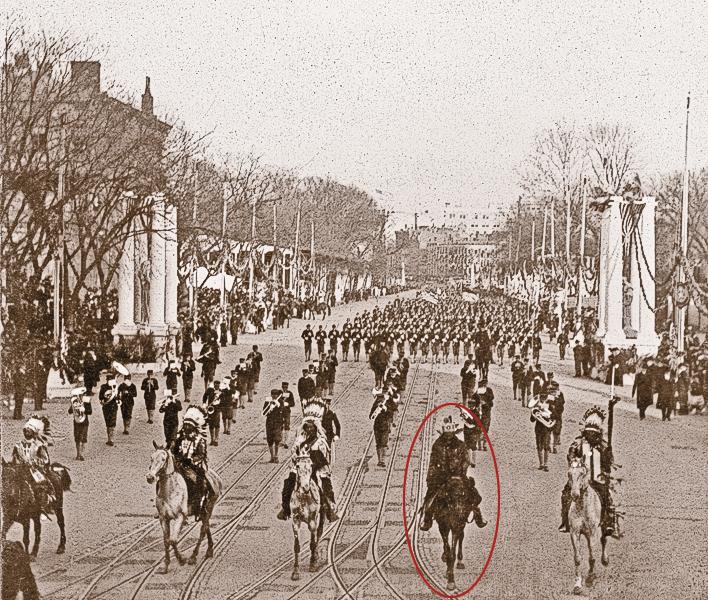

Geronimo’s celebrity status earned him the lead spot in a parade of Indian chiefs who passed in review before President Theodore Roosevelt on Inauguration Day in 1905 in Washington, D.C.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

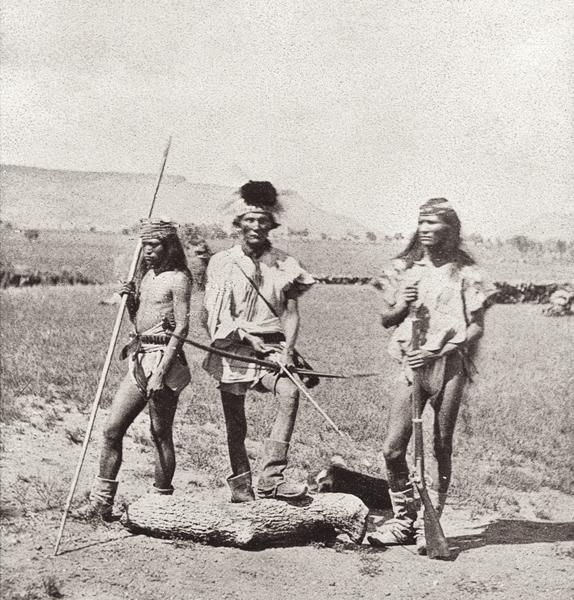

One of the pioneer photographers of Southwestern Indians, Timothy H. O’Sullivan traveled with Lt. George M. Wheeler’s survey west of the 100th Meridian during 1871-74. After some boats capsized, few of his 300 negatives survived the trip back East. This one, of “Apaches Indians, as they appear ready for the war-path,” made it.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Frank Fiske photo; True West archives –

In 1891, John Grabill’s camera captured this view of a Brulé Lakota tipi camp, near South Dakota’s Pine Ridge Reservation, with their horses stationed at the White Clay Creek watering hole.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Frank Fiske photo; True West archives –

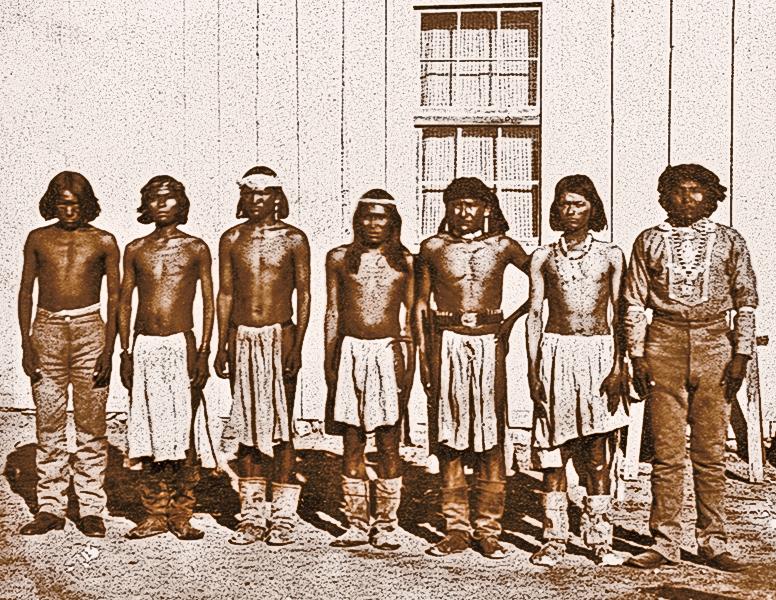

When Apaches abducted Felix Ward in 1860, they wore loincloths and moccasins. Seventeen years later, at the Camp Verde reservation in Arizona, white man’s clothing was just coming into vogue. Ward stands among them, second from right; he had joined the U.S. Army as a scout in 1872 and would even attempt to track down the renegade Apache Kid.

– Courtesy Sharlot Hall Museum –

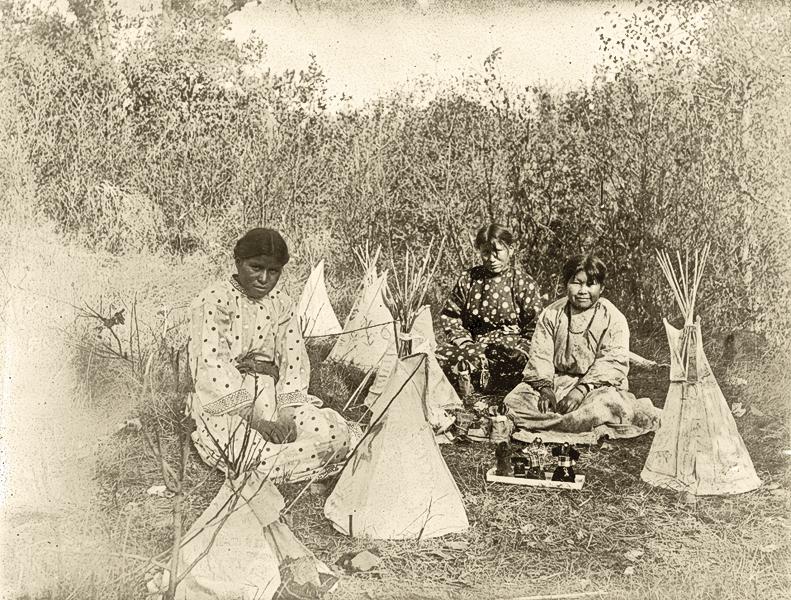

On the reservation in Lame Deer, Montana, Julia Tuell photographed Northern Cheyenne girls taking care of their deerskin dolls and arranging their small tipis in a circle just as their elders did in the big camp.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Frank Fiske photo; True West archives –

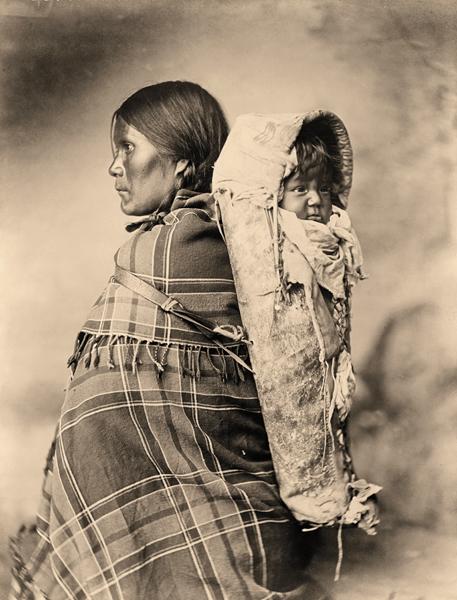

The Utes traditionally made cradleboards out of willow, but the reservation period began a trend of inserting boards into buckskin sacks, like the cradleboard holding Peearat’s baby in this 1899 photograph.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

– Frank Fiske photo; True West archives –

– Frank Fiske photo; True West archives –

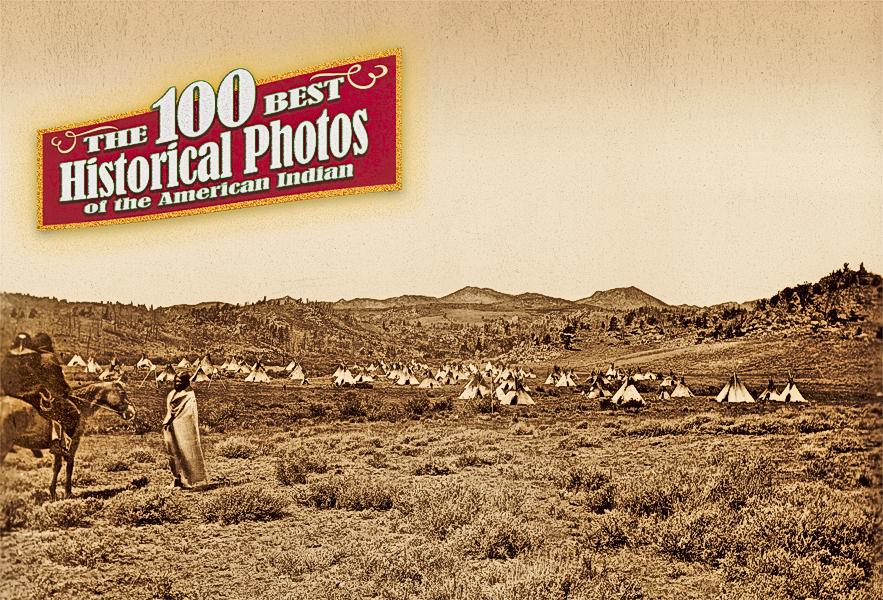

After the Civil War, government-sponsored expeditions furthered the record of the frontier West. Photographer William Henry Jackson traveled the farthest, when he joined Ferdinand Hayden’s 1870 survey. This Jackson photo of Shoshone Chief Washakie’s band and encampment near Wyoming’s Wind River Mountains is among the earliest photographs of native tribes prior to reservations.

– Courtesy Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology –

– Frank Fiske photo; True West archives –

– Frank Fiske photo; True West archives –

– Frank Fiske photo; True West archives –

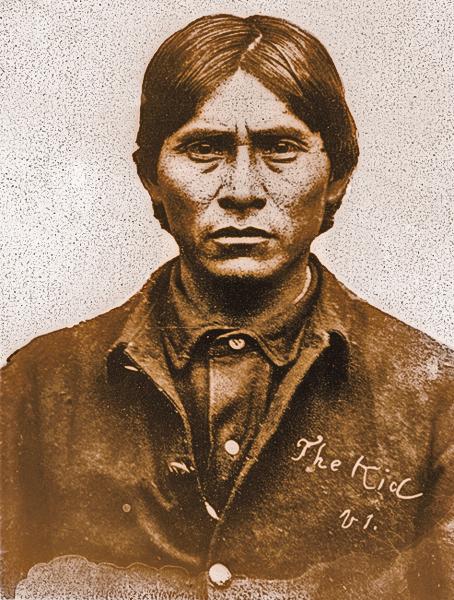

While scouting for the U.S. Cavalry during the 1880s, he was known as the Apache Kid. His people called him Haskaybaynayntayl, which means “brave and tall and will come to a mysterious end.” Quite a fitting name, since he disappeared after escaping during a transport to Arizona’s Yuma Territorial Prison in 1889.

– True West Archives –

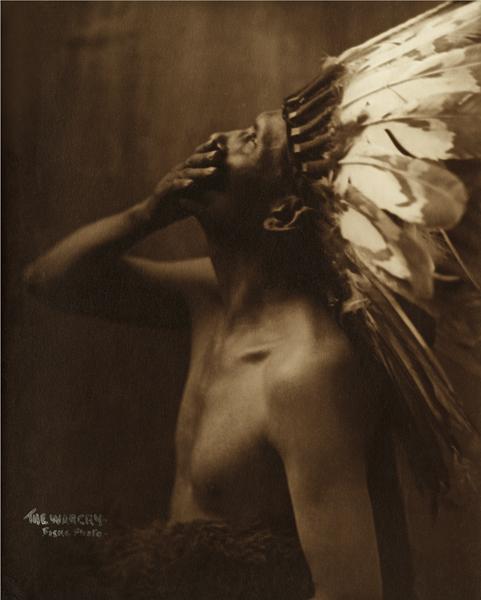

This powerful view of a Hidatsa holding an eagle as he stands on a large rock overlooking a valley conveys why so many Edward S. Curtis photographs speak to us today.

– Courtesy Library of Congress –

George Bird Grinnell invited Edward S. Curtis to photograph the Blackfoot in 1900, and a tour that included this photograph would lead, six years later, to J.P. Morgan funding Curtis’s monumental The North American Indian project.

– True West archives –

– Frank Fiske photo; True West archives –

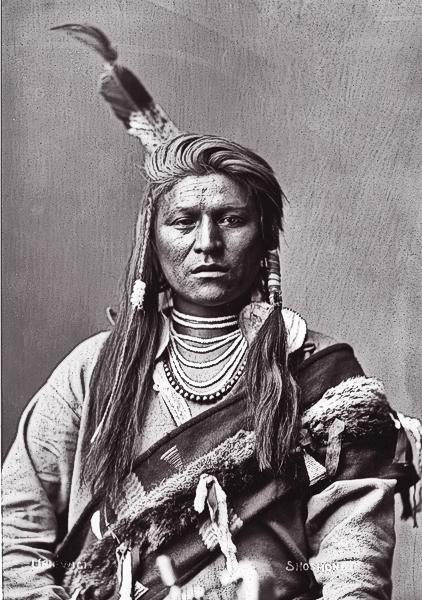

As one of the delegates from the Lemhi and Fort Hall agencies who signed the treaty of May 14, 1880, Uriewici, a Shoshone also known as Jack Tendoy, was photographed by Charles M. Bell in Washington, D.C. Ultimately, the Shoshone, Bannock and Lemhi would be moved to the Fort Hall area of Idaho.

– Courtesy Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology –

– Frank Fiske photo; True West archives –