Cody, Carr, Collins and Townsend could hardly contain themselves. On a hot afternoon at Fort Laramie, Buffalo Bill was his customary dashing and exuberant self, straight and slender and wearing a scarlet shirt as he paraded in front of John Collins’ post-traders store, with the back-slapping Fifth Cavalry lieutenant colonel, Eugene Carr, at his side, and Fort Laramie’s serene commander Major Edwin Townsend of the Ninth Infantry, in the boisterous knot. All were old friends who had not seen each other in a long while.

Cody, Carr, Collins and Townsend could hardly contain themselves. On a hot afternoon at Fort Laramie, Buffalo Bill was his customary dashing and exuberant self, straight and slender and wearing a scarlet shirt as he paraded in front of John Collins’ post-traders store, with the back-slapping Fifth Cavalry lieutenant colonel, Eugene Carr, at his side, and Fort Laramie’s serene commander Major Edwin Townsend of the Ninth Infantry, in the boisterous knot. All were old friends who had not seen each other in a long while.

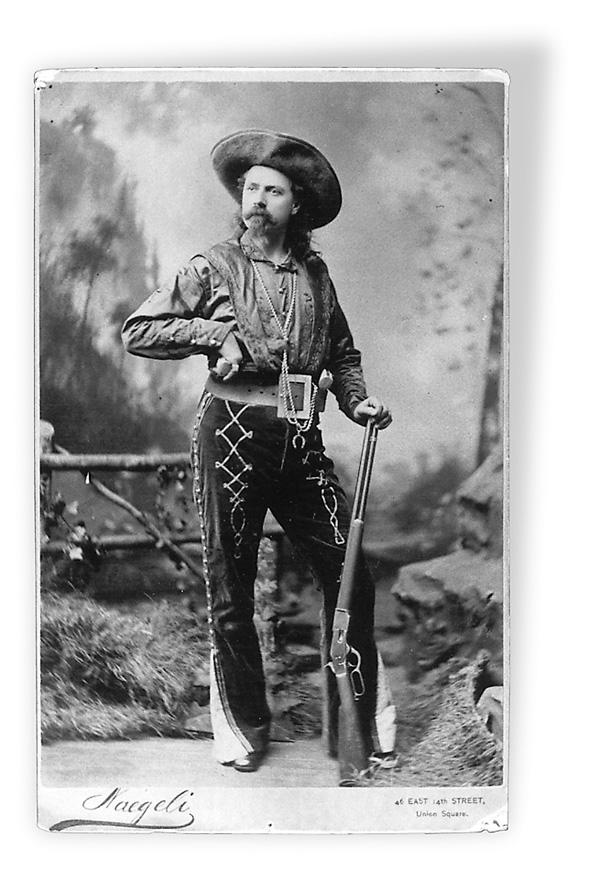

Cody, of course, had become a successful touring performer long ago, appearing on an eastern stage as recently as two weeks before. But now it was June 1876 in isolated Wyoming, in the midst of an Indian war, and these veterans were together again.

In the baking sun and with Cody always the center of attention, the knot of men told ribald stories on themselves and one another. Others peered on and shouted greetings. First Lieutenant Charles King of the Fifth Cavalry, like Carr, a Cody friend from earlier days in Nebraska and Kansas, reminisced with the famed scout about other campaigns. Among all, confidence was unchecked. Recalled one veteran Fifth Cavalryman: “All the old boys in the regiment upon seeing General Carr and Cody together, exchanged confidences . . . that with such a leader and scout they could get away with all the Sitting Bulls and Crazy Horses in the Sioux tribe.”

Fort Laramie was abuzz in early 1876. Positioned in eastern Wyoming, where myriad trails necked across a new bridge spanning the North Platte River, the fort’s denizens watched steady streams of traffic bound northwestward to Fort Fetterman, northward to the new Black Hills gold fields, northeastward to Camp Robinson and the Red Cloud Agency in Nebraska and south to Cheyenne and the Union Pacific Railroad. Since 1849, Fort Laramie had protected trail traffic, but now the pace was more intense, the gleam of gold in prospectors’ eyes more immediate, and the fear of Indian hostility, especially along the Black Hills road straight north, disquieting, and on too many occasions alarmingly real.

Fort Laramie’s summer garrison was pitifully under strength, with but single cavalry and infantry companies tending to internal business, in addition to the demands of trail and telegraph maintenance, as well as emigrant protection. Its other horse and foot companies were long absent, having joined Brigadier General George Crook’s new Big Horn and Yellowstone Expedition in northern Wyoming. At last report, Crook’s column was preparing for a movement into Montana, but that news was old.

Especially stirring to Fort Laramie’s inhabitants in June, was the streaming arrival of companies of the Fifth Cavalry. Fresh from service at Fort Hays, Kansas, and before that, engaged in prolonged combat against Apache Indians in Arizona, the Fifth was among many new cavalry and infantry regiments directed by Lieut-enant General Phil Sheridan to fight the Sioux.

Soon eight companies of the regiment were refitting at a cavalry camp mid-way between the fort and the North Platte Bridge. With horses to shoe, leather gear to repair, lost or missing equipment to replace, and munitions and rations to be fully issued, the troopers were plenty busy. When opportunity allowed, the men also stole away to Collins’ well-stocked traders store, where tastier foodstuffs, candies, alternative kerchiefs and hats, and all-important chewing and smoking tobaccos lured those with loose change in their pockets.

At Sheridan’s direction, the Fifth was bound for service on the Fort Laramie-to Black Hills trail where, until directed again, they would safeguard this heavily used stage and emigrant road, especially where it crossed the infamous Powder River Indian Trail. The latter was the principal way west for thousands of Sioux and Cheyenne Indians who resided seasonally at the Red Cloud and Spotted Tail Indian agencies in northwestern Nebraska. This year, the lure was both the vast buffalo herds in Wyoming and Montana, and also Sitting Bull’s and Crazy Horse’s warrior camps.

With Carr in the lead and Cody and Baptiste “Little Bat” Garnier scouting the front, some 350 officers and men of the Fifth Cavalry departed Fort Laramie on June 22 heading northward toward the Black Hills. Sergeant John Powers of Company A remembered, “The boys are all in good spirits, and eager to be in active service.” The trooper’s glee at having joined this great Indian war was shaken just the next day, however, when news was received via Fort Laramie that Crook had engaged the Sioux at Rosebud Creek, Montana, on June 17, and instead of pressing any advantage was retiring to a base camp in northern Wyoming. Retiring from the scene of combat was not a good sign.

The Fifth’s spirits were shaken all the more when on July 6 a devastating report was received that Custer and half of his Seventh Cavalry had been annihilated on Montana’s Little Big Horn River on June 25. The officers speculated that surely they would be ordered north to Crook’s camp. Thus far, their meanderings on the Black Hills road had proven fruitless, with rarely an Indian seen. The Indians’ Powder River Trail was unusually quiet.

On July 12, the Fifth received orders to return to Fort Laramie, to hurriedly resupply and embark for Crook’s camp on Goose Creek in northern Wyoming. Crook was concentrating additional troops for renewed campaigning on the northern front. Colonel Wesley Merritt now commanded the regiment, having arrived in the Fifth’s Cheyenne River camp on July 1. A Sheridan protégé and Custer peer, Merritt hurried his regiment southward to Fort Laramie anxious to resupply and depart for more active campaign country.

Within an easy final day’s ride of the fort, however, on July 13 Merritt learned from Townsend who was stationed at Fort Laramie, that hundreds of Cheyenne Indians were reportedly bound from the Red Cloud Agency to Sitting Bull’s camps in Montana. In the wake of the Powder River, Rosebud Creek and Little Big Horn disasters, this was disquieting intelligence in military circles. Merritt promptly dispatched Major Thaddeus Stanton, one of Sheridan’s emissaries, and Captain Emil Adams’ Company C directly to Camp Robinson to investigate the report.

In a breakneck race to Camp Robinson and back, Stanton confirmed news that as many as 800 Northern Cheyennes and some Sioux had departed the agency to join Sitting Bull, traveling westward on the Powder River Trail. Trusting that Sheridan and Crook would prefer that he intercept and turn back these potentially hostile Indians rather than continue on the trail to Fort Laramie, Merritt turned back and commenced a race north to a small infantry camp on Sage Creek, and from there east into northwestern Nebraska to an intersection of the Powder River Trail at its Warbonnet Creek crossing. Ever after, the regiment reveled in this heroic ride, traversing some 85 miles in a 31-hour forced march to place themselves immed-iately in front of the unsuspecting Cheyennes.

Only as the sun rose on July 17, 1876, did Merritt and his men fully appreciate their surroundings. They had come to this Warbonnet Creek camp well after dark, but now could see the creek’s high cut banks immediately east of them. The cover was perfect. Protruding from the broad, elevated flats east of the cut banks were two conical hills, each affording perfect views of the Powder River Trail as well as miles of rolling landscape stretching between them and the distant Pine Ridge and Red Cloud agencies, the latter some 30 miles away and unseen. Merritt immediately ordered observers to the hilltops. First Lieutenant Charles King occupied the southern hill, while trooper Chris Madsen, who later became a famous Oklahoma lawman, was positioned on the northern hill.

Buffalo Bill Cody, meanwhile, seized the opportunity in the breaking daylight to ride a circular route eastward to locate the Indians, doubtless not far away. At about 4:15, King and an enlisted man from his company were the first to spot Indians, a small group of riders who had come over a ridge about two miles away. These warriors, including Beaver Heart, Buffalo Road and Yellow Hair, were members of Little Wolf’s band of Cheyennes. They had been sent ahead to look for soldiers. The main Indian camp was about seven miles behind them.

Quickly the Cheyennes indeed saw soldiers, not the secreted Fifth Cavalry companies well hidden behind Warbonnet’s cutbanks, but instead two couriers advancing ahead of Merritt’s distant supply train. Believing that they were the hunters and not the prey, the leading warriors and others from the village furtively advanced westward down a broad swale leading straight to Warbonnet Creek and the seven companies of well-hidden Fifth Cavalrymen.

As the drama unfolded, Cody, Merritt and Carr joined King on the hillock overlooking the scene. Behind them they observed the regiment, the men having closed tight on the creek’s cut banks where they waited, dismounted and fidgeting with their weapons and mounts. Ahead they saw the Cheyenne warriors cautiously advancing to cut off the unsuspecting couriers. To the rear, Cody and the officers saw two equally unsuspecting couriers riding vigorously to their comrades, who they could not see but whose trail was plain and barely hours old.

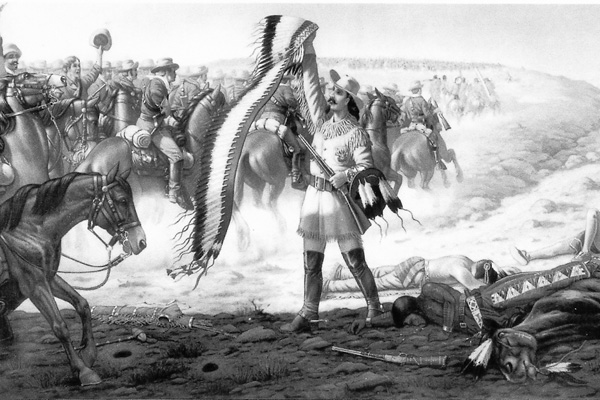

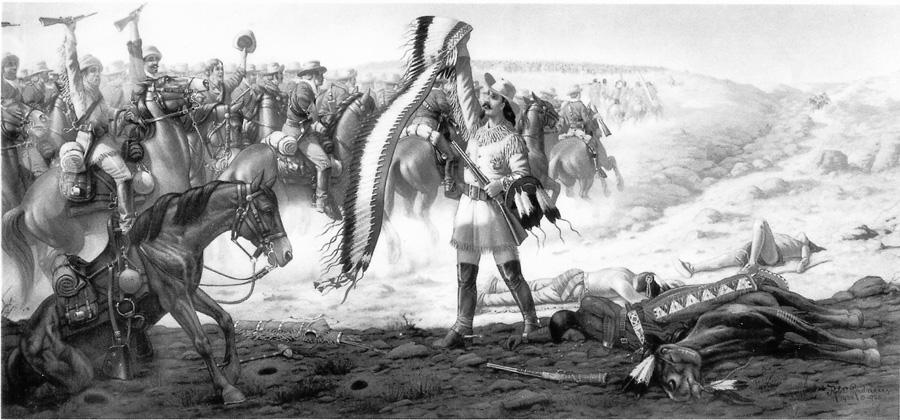

Buffalo Bill was the first to recognize the opportunity unfolding before him. Ever the showman, he was appropriately dressed in a colorful Mexican vaquero stage outfit. This included an extra wide black belt, crimson shirt, and flared velvet pants that he had worn on the stage just weeks earlier in a play titled The Scouts of the Plains. Cody saw where he and a small cadre of followers could easily whip those Indians coming toward them while the rest of the regiment scurried after the distant camp. Merritt agreed, telling everyone to get in place and ordering King to give the sign. Hurriedly Cody, his pal Jonathan “Buffalo Chips” White, and several men from King’s Company K scampered to the mouth of the long ravine that the Indians were now descending. Merritt and Carr positioned themselves at the base of the hillock below King to lead the troopers when they ascended from the creek bottom.

A few moments of anticipation passed. King peered cautiously with his binoculars over the brow of the hill at the Indians. Southwest of him he could see Cody and his followers. Behind and below him he could see his superiors, and behind them along the creek the near 300 members of the regiment, all poised to surprise the Cheyennes.

Unsuspecting, the warriors closed to within 90 yards of Warbonnet Creek when King jumped up and shouted down to Cody, “NOW, lads, in with you!”

Instantly, Cody and his friends spurred their horses out of the creek bottom and loosed a volley at the warriors. King fired too. Surprised, the Cheyennes returned fire, toward both Cody and King. After the initial volley, those supporting Cody sought cover. So, evidently, did those riding with Yellow Hair. But both Cody and Yellow Hair fired additional rounds at each other. One shot from Yellow Hair caused Cody to either fall or dismount from his horse. Neither was hit, but Cody quickly remounted and fired again, and this time, he killed the young warrior.

In ensuing years, this deliberate and careful exchange of carbine fire between two skilled marksmen would be redescribed and embellished as a highly dramatic hand-to-hand duel. These fabrications certainly made great fodder for show business publicity. Cody shamelessly exploited the fabrications, often to the chagrin of other Fifth Cavalry veterans present during the skirmish who winced at the embellishments. In fact, however, the Cody-Yellow Hair “fight” did amount to a heroic action in combat: each combatant facing the other’s bullets and only one surviving.

Cody closed on the fallen warrior as several companies of the Fifth Cavalry rode by. Sergeant John Hamilton of Company D offers the best survey of the scene, having ridden within yards of the dismounted Buffalo Bill. Yellow Hair was laying face down, Hamilton remembered, with his arms folded under his head. He wore a paint bag, a scalp of yellow hair from some young white woman (thus his name, Yellow Hair), tin bracelets on his arms, war feathers, a neck charm, beaded belt, and a cotton American flag as a breechcloth.

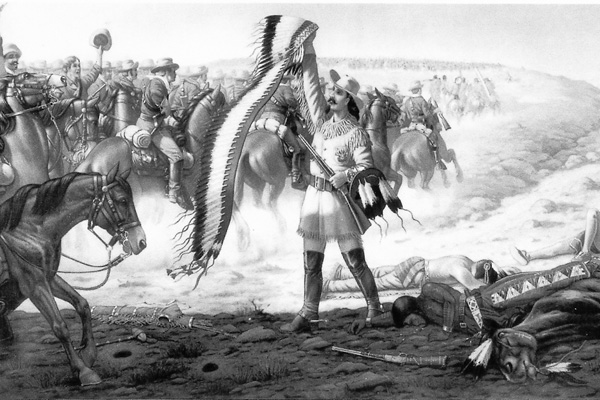

As the soldiers came on, Cody pealed off Yellow Hair’s top knot, a circle of scalp about two inches in diameter with black hair about 15 inches long, and waved it aloft shouting amid deafening cheers, “The first scalp for Custer.”

Buffalo Bill collected Yellow Hair’s feather bonnet, shield, bridle, quirt, arms and scalp, which later he boxed and mailed to a friend in Rochester, New York. The regiment, meanwhile, scampered after the scattering Cheyennes. In their hurried flight back to the Red Cloud Agency, the tribesmen littered the prairie with blankets, foodstuffs, and other weighty items. The regiment incurred no casualties in the fight and chase, aside from one private hurt when his horse fell down an embankment. Yellow Hair was the lone Indian casualty. Remarkably, after the Fifth Cavalry gained the Red Cloud Agency at the close of the day, many of the Cheyennes came to the soldiers’ bivouac to talk the episode over with them. At the agencies, enemies in the morning could be friends at night.

At first blush, and compared with other battles and skirmishes of the bloody Great Sioux War of 1876-1877, the affair on Warbonnet Creek, Nebraska, on July 17, 1876, seems hardly worthy of a mention. Only one casualty was recorded, not hundreds like at Little Big Horn or dozens common at places like Rosebud, Slim Buttes, Red Fork of the Powder, Tongue River and Muddy Creek.

But for the first time in the deplorable first months of the war, Sheridan’s army could boast of a successful encounter with northern Indians who until then had held sway over the frontier regulars. Warbonnet Creek did offer a celebrated “first scalp for Custer,” an act of atonement for the horrors of the Little Big Horn. And many of the Cheyennes never made it to Sitting Bull’s and Crazy Horse’s camps to help prolong the conflict, though certainly some did later.

Warbonnet’s lasting importance emerged sometime after. The “first scalp” episode became a highly memorialized public drama repeated for decades in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows and on the silver screen in a number of Cody movies including his own celebrated film, Buffalo Bill’s Indian Wars of 1913. Warbonnet, too, has been featured on an inordinate number of well-developed canvases by some of America’s foremost artists and illustrators, including Charles Russell and Robert Lindneaux, rivaling the Little Big Horn in the pantheon of American Indian wars battle art. Warbonnet Creek is venerated in two on-site cobblestone monuments at a site that is still virtually lost in distant northwestern Nebraska. But perhaps most importantly, Warbonnet Creek is indelibly burned into the psyche of those who, to this day, are fascinated by the events, large and small, of the Great Sioux War—America’s greatest Indian war.

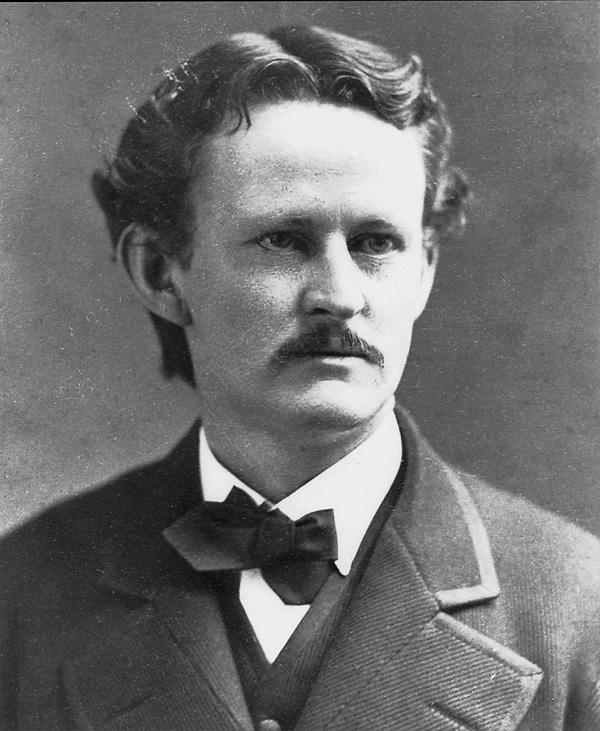

PAUL L. HEDREN is a National Park Service superintendent of Niobrara-Missouri National Scenic Riverways and the author of several books, including First Scalp for Custer (1980), Fort Laramie In 1876 (1988), Campaigning With King (1991), and Traveler’s Guide to the Great Sioux War (1996).

Photo Gallery

– Buffalo Bill Historical Center –

– Paul Hedren Collection –

– Paul Andrew Hutton Collection –

– True West archives –

– True West archives –

– Buffalo Bill Historical Center –

– Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument –