— “The Trapper’s Last Shot” by William T. Ranney, Courtesy The Beinecke Library, Yale University —

“Yet was he modest, never obtrusive, charitable, ‘without guile,’…a man whom none could approach without respect, or know without esteem. And though he fell under the spears of the savages, and his body glutted the prairie wolf, and none can tell where his bones are bleaching, he must not be forgotten.”

Prelude

The anonymous eulogy to Jedediah Smith was published in Illinois Monthly Magazine in June 1832. The author’s view of Jed Smith’s character and motives differs from the views of Maurice S. Sullivan and Dale L. Morgan, the scholars who have worked most fully on his life. I see Smith as a man torn by conflicting allegiances—the values of his church and his society, and the values he learned and lived by in the wilderness. The evidence of his letters to his family seems to be that he judged his life as a mountain man to be wicked; that conviction seems to have been deep and sincere. He seems to have damned himself for his love of wildness in the same way that settlers would later damn most mountain men for it. So he went home in an attempt to live by his beliefs he professed.

Smith says nothing about his decision to return to the mountains in 1831. Though it was only a partial turning back to his former way of life, I think it expressed a strong-felt need, a need he probably chastised himself for. So what is remarkable here, to me, is the conflict between professed values and the values he actually lived by. When his anonymous eulogist said that Smith made his altar the mountaintop, he meant that as a tribute to Smith’s ability to live in Christian faith in the mountains. The irony may be that Smith made the mountaintop his altar in a different sense—that he replaced, symbolically, the altar of the Christian Church with his mountaintop as an object of worship.

I believe that Smith, had he lived, would have been unable to stick to his decision to become a respectable citizen of the settlements.

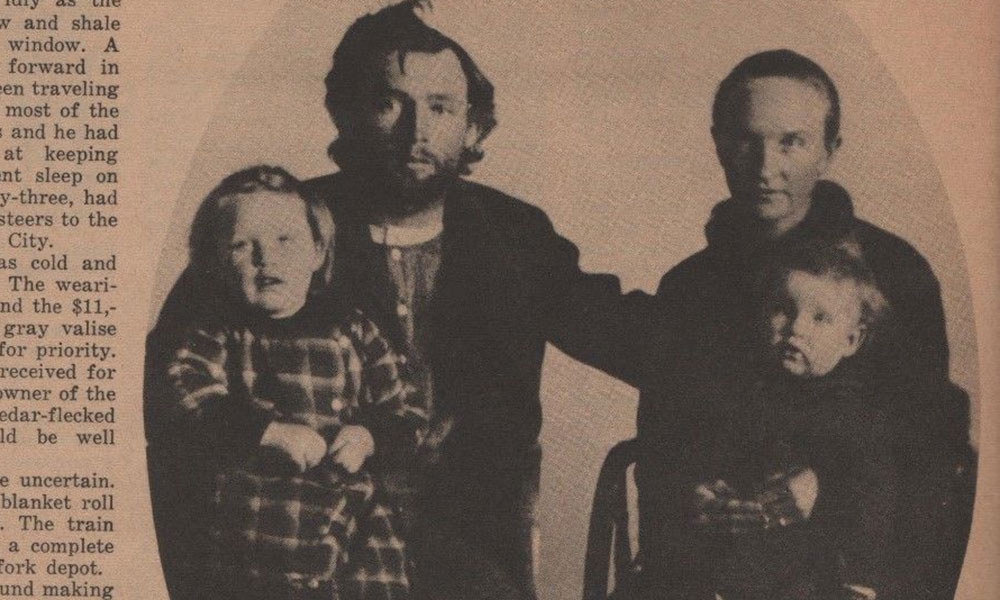

— True West Archives —

The Pious Man of the Mountains

Jed had been aware, from the beginning that he was unlike most of the men in the mountains. He was learned, for one thing. He was serious—serious about his religion, serious about turning a profit, serious about writing a book and making maps. He didn’t go for debauchery: He stayed away from Indian women and didn’t join in the rendezvous carousing. He tried to practice his religion in a profane environment.

Jed, a Christian in the Puritan tradition, regarded making money as one of a man’s positive duties, and thought of unused capital as an evil. He now had to decide on some use for his capital. Well, he might go to Ohio and that farm eventually, but he wanted some business venture in the meantime. The role of gentleman farmer may have pulled at his fancy, but not strongly enough. He hired Samuel Parkman, a young man who had gone to the mountains in 1829 and come back with Jedediah, to copy out his journals and help him make his maps. That was one important enterprise.

He also thought that he might go into a partnership with Robert Campbell. He discovered, though, that his Irish friend had gone home to Ireland; Robert’s brother Hugh, who lived in Richmond, Virginia, informed Jed that Robert’s health was failing again. He wrote to Hugh with good wishes for Robert’s well-being and a fervent wish that the two friends might be together again. In the spring, he added, he would still have capital to start a business with Robert.

Younger brothers Peter and Austin had wanted to follow ’Diah to the mountains. Another young man, J. J. Warner, came to Jed for advice on how to become a mountain man; Jed talked him out of such a pagan life. So Jed began to think of the West again—not Absaroka and Cache Valley, this time, but Santa Fe. Maybe he could explore the possibilities of trade with the Mexican provinces.

He missed the mountains. Writing t o Hugh Campbell on November 24, 1830, just a month back from the mountains, he admitted, “I am much more in my element, when conversing with the uncivilized Man, or Setting My Beaver Traps, than in writing Epistles.”

He decided to put off going home. He did miss his father, his teacher Dr. Simons, and his brother Ralph. But that could wait. Business, he told them, was too pressing. He didn’t add that the lure of wild country was too strong.

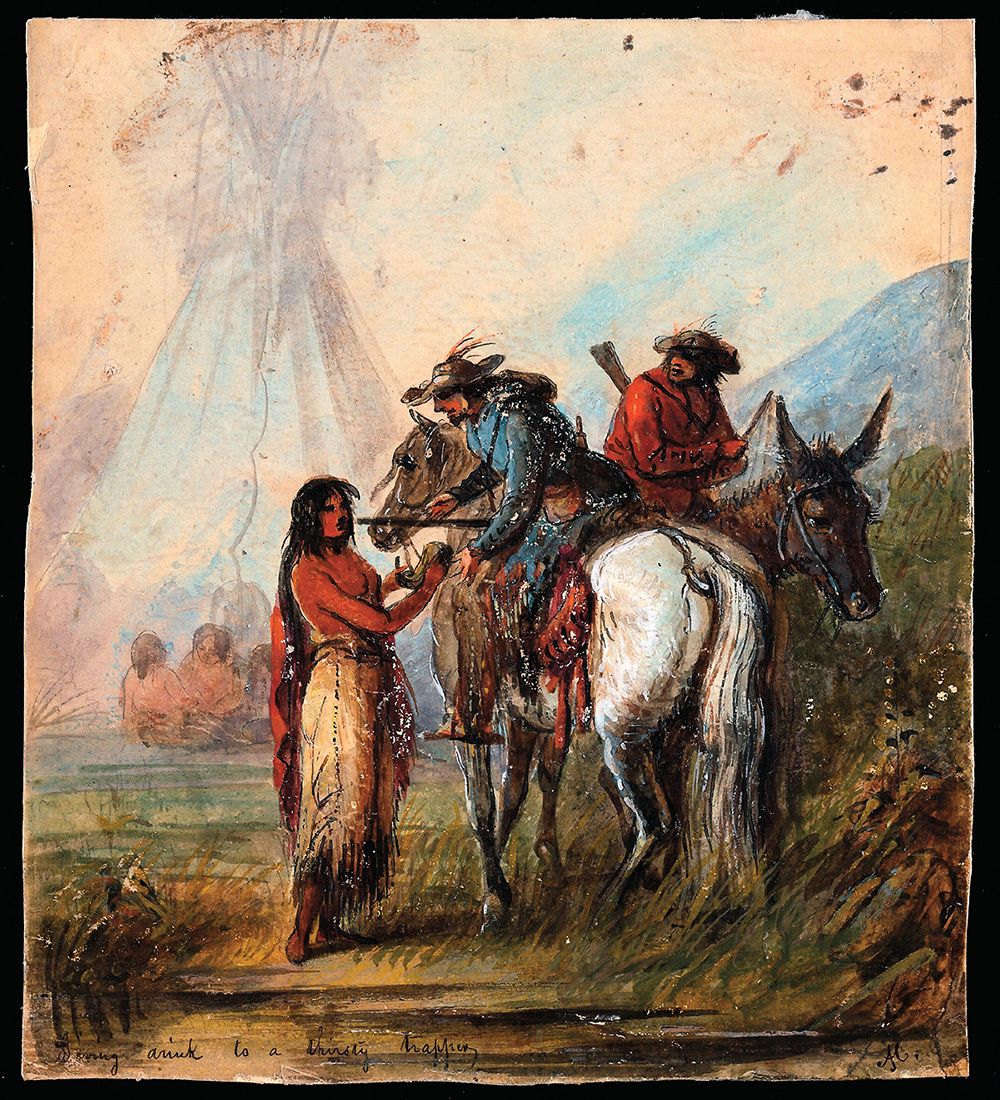

— “Giving a Drink to a Thirsty Trapper” by Alfred Jacob Miller, Courtesy The Beinecke Library, Yale University —

He made up his mind for Santa Fe. That was less risky than beaver trapping, even though the route lay through Indian country. He knew the business of supplying, and plenty of trappers were operating out of Santa Fe and Taos. He could get Peter, Austin, and J. J. Warner started in the world, give them a taste of the trail and the mountains, and still not be shot at by Blackfeet. At first he thought that he himself might not go along—he’d just handle the business end. But by the end of January, Jed had determined to hit the trail again. He wrote General Ashley for help in getting a passport.

He could explain it all to himself. He was making a good investment; he was going into a business he knew; he was g iving a hand to young men of enterprise. Besides that, he could go beyond Santa Fe and see the Southwest. That was the only part of the entire West he did not know firsthand; a trip there would let him complete his map. He didn’t have to believe that he was giving in to the perverseness of his wicked heart, or to an uncivilized love of wild places.

Bill Sublette and David Jackson, meanwhile, had been waiting for Tom Fitzpatrick to arrive with confirmation of their deal to take supplies to rendezvous in the summer of 1831. But Fitzpatrick had not shown up. They had already arranged to buy the provisions and equipment. Stuck, they elected to go with Jed. Legally, the two parties would be separate, and Sublette-Jackson would get an independent passport and hire their men and sell their goods independently. But the outfits would travel together as far as Santa Fe. So, by late March of 1831, Jedediah Smith, who had tried to commit himself to the settlements by buying a farm, a fine house and two servants, was back in the mountain trade with his old partners.

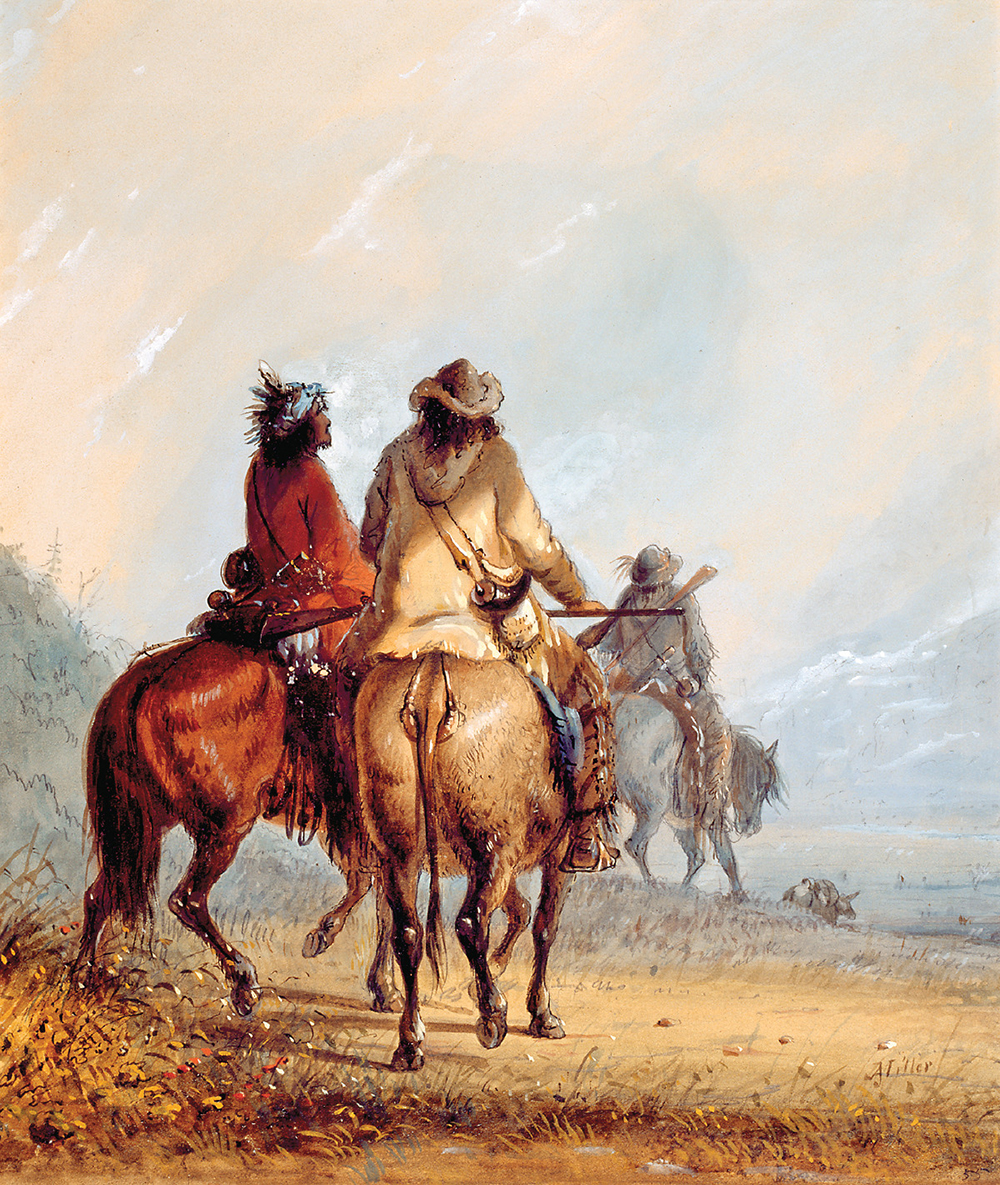

— “Mural of Western Trappers and Mountain Men” by Alfred Jacob Miller, Jackson Lake Lodge, Courtesy Gates Frontiers Fund Wyoming Collection within the Carol M. Highsmith Archive, Library of Congress —

The Siren Call of the Trail West

They set out from St. Louis on April 10 with 22 wagons, including one bearing a six-pound cannon, and 74 men. Before they reached the frontier, two more independent wagons and nine more men joined them. Near Lexington, Missouri, they camped for final preparations. Jed took the precaution of making a new will, since he was heading back into Indian territory. But they still had several hundred miles of beautiful rolling plains before any possible danger.

Then they had a surprise in camp: Tom Fitzpatrick rode in. He was headed for St. Louis, two months late, to contract with Sublette and Jackson for supplies for the 1831 rendezvous.

The Irishman explained: Henry Fraeb and Jean Baptiste Gervais had gone to Snake country; Jim Bridger, Milton Sublette and he had moved back to the Three Forks area, again in strength, to cash in on Blackfoot country. They had made a good hunt; but during the winter they had heard nothing from their other two partners. Finally they decided to take a chance on buying a new outfit anyway. But Fitz hadn’t gotten away until March to make the express to the settlements. What could be done about the outfit?

Jackson and Sublette were not carrying exactly what they would have taken to the mountains. They were supplying two towns as well as possibly some trappers. They decided that if Fitzpatrick would go along to Santa Fe, they would supply him there. Sublette and Jackson would let him have two-thirds of the outfit, and Smith the other third. The credit of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company was good with these old friends. But Fitzpatrick would have to get the goods to rendezvous on his own. And since it was already into the first week of May, he would be plenty late.

So they set out for Council Grove. They had no troubles that they weren’t used to—drizzle for days at a time, miry ground and willful mules. At Council Grove they stocked up on wood for axles—the country was barren from here on—and got organized into disciplined units for traveling safely through Indian territory. Before long a war party made a charge on the wagons, but the cannon scared them off. A little later the clerk for Sublette and Jackson dropped behind the party to hunt and was killed by Pawnees. The Santa Fe Trail was not looking as trouble-free as it was supposed to be. This expedition, though, had an unsurpassed congregation of masters of the craft of the plains and the mountains. Jed Smith, Bill Sublette, David Jackson and Tom Fitzpatrick were four of the half-dozen most skilled mountain men living.

— “Trappers Starting for the Beaver Hunt” by Alfred Jacob Miller, True West Archives —

The Cimarron Cutoff

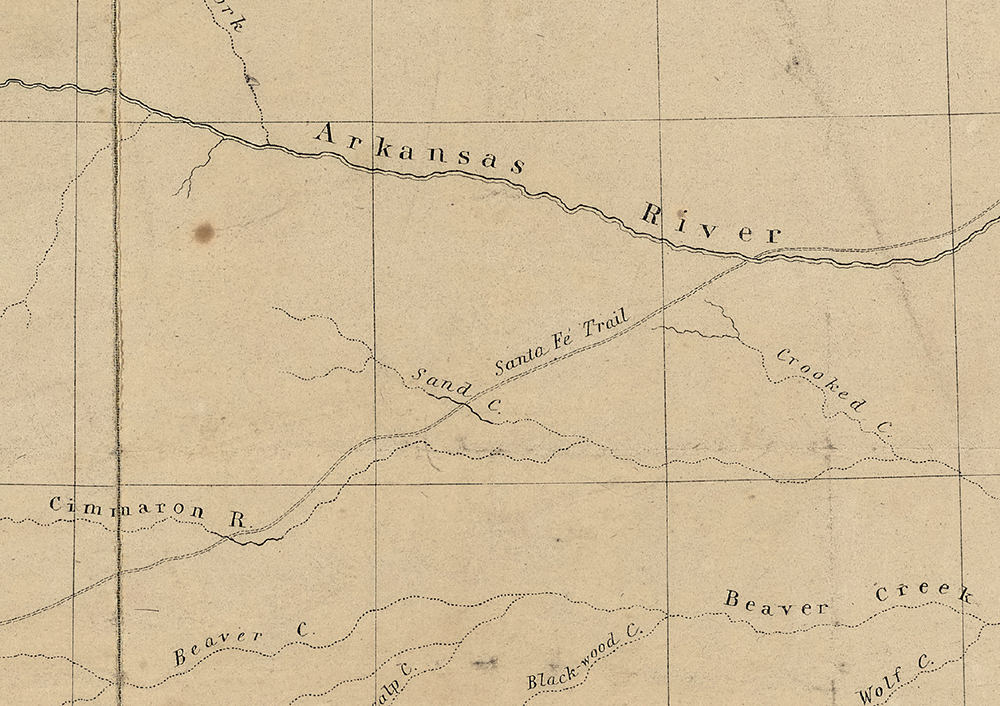

They followed the Arkansas River southwest for over a hundred miles to come to the place where the route forked. The round-about way was easier and safer—along the river to the mountains and then due south, through Raton Pass, to Santa Fe. The short way was quick but treacherous. It was a straight line across the Cimarron Desert. It was a scorched country without water, without any landmark, crisscrossed by buffalo trails that disguised the wagon road and could lead a party the wrong way and into a torturous death by thirst. They took the Cimarron Cutoff. If anybody knew how to cross a desert and find water when he had to, it was Jed Smith.

In the confusing maze of buffalo trails, even these old hands lost their way. Soon they had spent three days without water. The animals were about to die. The men were delirious with thirst. Discipline was breaking down and small groups were wandering through the desert in a desperate search for water.

So Jed did what needed doing. Taking Fitzpatrick with him, he pushed ahead of the wagon train to try to find a water hole or a spring. He knew that the Cimarron meandered out there somewhere. Even if it was as sporadically wet as the Inconstant River, he would find a hole and dig for water.

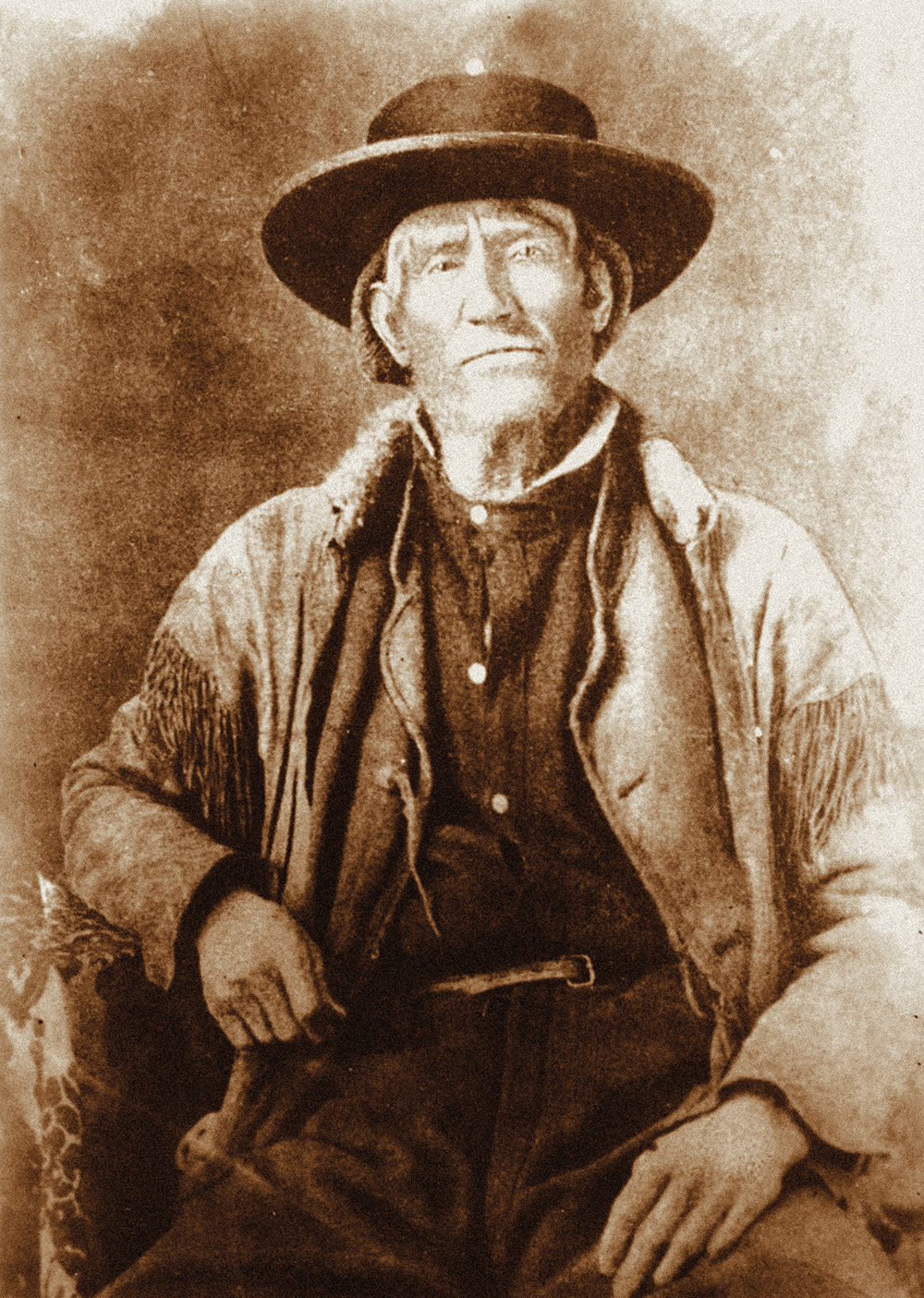

— True West Archives —

The two men came to a hollow that should have had water. It was dry. Jed told Fitzpatrick to stay there, dig for water, and tell the main party in which direction he had gone. He was going to look further ahead. It was a dangerous choice in Indian country, because a lone man was an irresistible temptation. But Jed had to take the chance. He found the dry bed of the Cimarron 15 miles further on. It was dried to sand in most places, but here and there were holes filled with liquid. Jed’s mind said caution: Buffalo holes would make good hunting spots for Indians and were likely to be watched. But his body cried out for wet. He rode down, let his horse walk in, and waded in himself.

After his pain eased, he got back on his horse. He would be able to save the wagon train now. But when he turned, Jed saw a band of 15 or 20 Comanches blocking his way. He realized they had crept up while he was splashing in the water. He knew his chances were slim: The Comanches had a reputation for savagery.

His one hope was to make a strong front of it. He rode straight up to them and made signs of peace. They paid no attention. Since he had his gun cocked, the Indians fanned out to either side, away from the line of his rifle. Jed watched to make sure they didn’t get behind him, and again tried to talk to their leader.

His horse was fidgeting back-ward. Suddenly the Indians began shouting at the horse and waving their blankets to frighten it. The horse wheeled and turned so that Jed’s back was to the flank of braves. Instantly, one of them fired and hit him in the shoulder. Jed gasped, his breath knocked away. He turned the horse around to front, leveled his Hawken, and killed the chief.

He grabbed for his pistols. A lance knocked his arm away from a handle. Two more blows, like sledgehammers, crushed his chest. He felt a falling, back and sideways, like falling in a dream, falling without stopping. He forced his eyes to register: Blue, a vivid blue. He couldn’t think what the blue might be. It darkened. And the sense of falling slipped away.

— “Scene of Trappers and Indians” by Alfred Jacob Miller, True West Archives —

Trail’s End

Jed Smith’s brothers and friends waited and waited for him. Finally, for the safety of the caravan, they moved on. They hoped that he would miraculously survive whatever had happened, as he had always survived, and catch up with them on the trail. When they got to Santa Fe on July 4, they heard the story of his death. Mexican traders had gotten it from the Comanches. Peter and Austin bought Jed’s rifle and pistols from the traders. Jed’s body was never found.

Jed Smith had made his traditional Christianity a deep principle within himself. But the love of wild places had rooted into him and become a deeper religion. His place of meditation was not the oak pew but the lone wilderness, as his eulogist said. His altar was the mountaintop, in a sense truer than his eulogist me ant. His sacraments were mountain skills. At the age of 32, he had lost his life in the service of his true church.

He had made a great pilgrimage to discover and know intimately the West he loved. For that mission he had risked, in his own eyes, even his salvation.

Though he died young, his quest had been successful. He had found the way across the Rocky Mountains at South Pass. He had led his men the length and width of the Great Basin. He had pioneered the overland route to California. He had become the first man to cross the Sierra Nevada. And he had been first to travel by land from California to Oregon. If the trappers were light years ahead of the American government and American people in their knowledge of the West, it was because Jed Smith had shown them the way. As an explorer of the West, he had come to rank with Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. Such were the accomplishments of the public man.

— John Charles Fremont’s 1846 map of his expedition to New Mexico and the southern Rocky Mountains Courtesy NYPL Digital Collections —

The private man had met his own standards in enterprise, courage, integrity and fairness. He had challenged the dangerous and the unknown with a fierce energy, and had thrived in them. He had spent his days living and feeling in the particulars—the creeks and meadows, the ridges and peaks—of the country he loved most, the Rocky Mountains.

A decade or two later, newspapers publicized the trapper garishly. Dime novelists idealized mountain men into heroes for wide-eyed boys and dreaming fathers. Kit Carson and Jim Bridger became epic figures, American versions of Odysseus. But then, when he should most have been remembered, Jedediah Strong Smith was forgotten.

Editor’s Note:

“Death of a Mountain Man: Jedediah Smith’s Last Trail” is excerpted from Give Your Heart to the Hawks: A Tribute to the Mountain Men (TorForge) by Western Writers of America Hall of Fame member Win Blevins. Originally published in 1973, Blevins’ masterpiece has been in print for nearly 50 years, a remarkable accomplishment for any work of history. As Blevins notes in the 40th anniversary introduction, “The men in these stories lived vigorously, daringly, adventurously. I hope readers will ride along with them for decades to come. It is good for the soul.” Amen.

In addition to Give Your Heart to the Hawks, Win Blevins is the author of over 35 books, including the Spur Award-winning Stone Song, a novel about Crazy Horse. He is proud to call himself a member of the world’s oldest profession—storyteller.