First the Dawes Commission, Now Casino Tribes, Profit by Erasing Indian Heritage

Starting in 1887, The Dawes Commission tried to shrink tribal membership down to zero. It’s happening again today, again it’s all about money, only this time, Natives are doing it to each other.

I am indebted to the University of Oklahoma for providing me with a 95-page file of original plaintiff and defense documents related to the Dawes Com-mission’s handling of claim #116, Chas. D. Sullenger, et al.

It all began with President Andrew Jackson’s Indian Removal Act of 1830, ordering the forced relocation of most of America’s Indian tribes to west of the Mississippi River. (Interestingly, in the documents, that event is referred to neither as Indian Removal Act nor Trail of Tears, but the innocuous Migration.) The Act created the Indian Territory, which would become Oklahoma, and it created the reservation system as we know it. Following the Indian Wars, which ended with Geronimo’s surrender in 1886, in 1887, the United States Government embarked on a new policy to deal with the nation’s Indian tribes. And by “deal with,” I mean the dismantling of the tribes.

While the purposeful destruction of another’s culture seems appalling today, it was seen then as benign. After all, America was the great “melting pot”: people from all over the world abandoned their oppressive governments and came here for freedom of opportunity and freedom of religion. Despite the fact that Indians had not sought out “America,” but had essentially been invaded by it, Americans intended to be kind, helping these “primitive people” shuck off what were seen as their failed cultures and become full, free Americans; to assimilate. One roadblock to that goal was that the reservations were officially independent nations, and the ownership of land was communal. The purpose of the Dawes Act of 1887, written by Massa-chusetts Senator Henry Dawes, was to abolish tribal governments, recognize state and federal laws, and divide the land, to give it to individuals who would, for the first time, own physical property, to farm or ranch, giving 160 acres to each head of a family. It was intended to increase personal wealth among Natives, decrease reliance on the state, and lessen the power of chiefs.

The Five Civilized Tribes–Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole–initially got a pass, but in 1893, President Grover Cleveland instructed the Dawes Commission to include them. To receive an allotment of land, tribal members had to register with the Office–later the Bureau–of Indian Affairs, and be entered on the Dawes Rolls. And they had to prove they belonged.

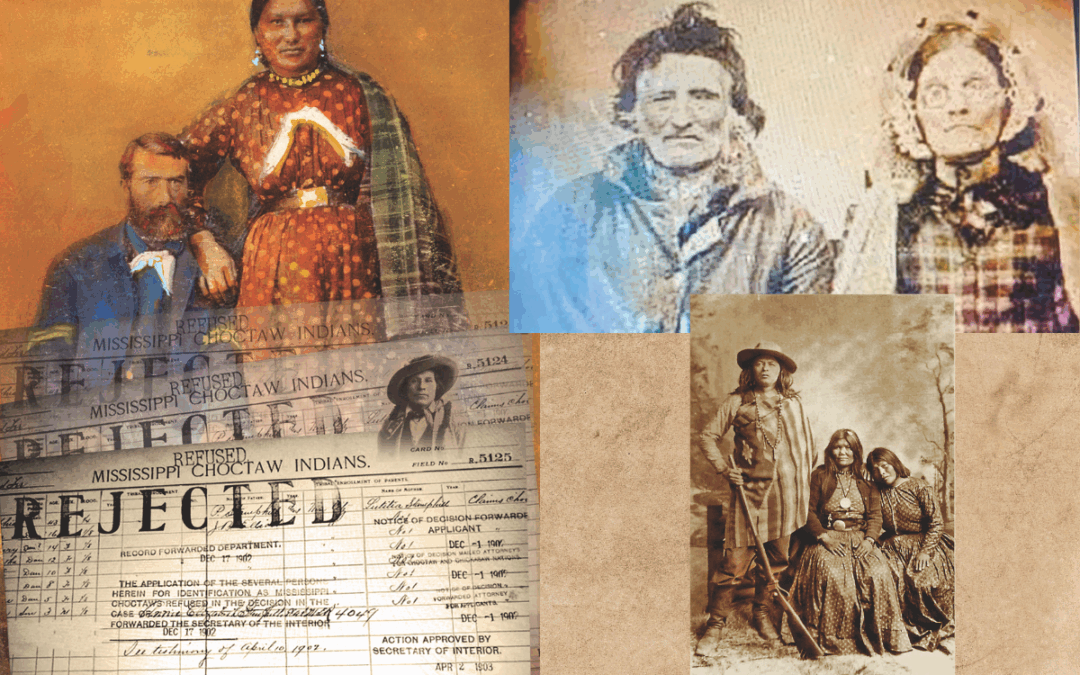

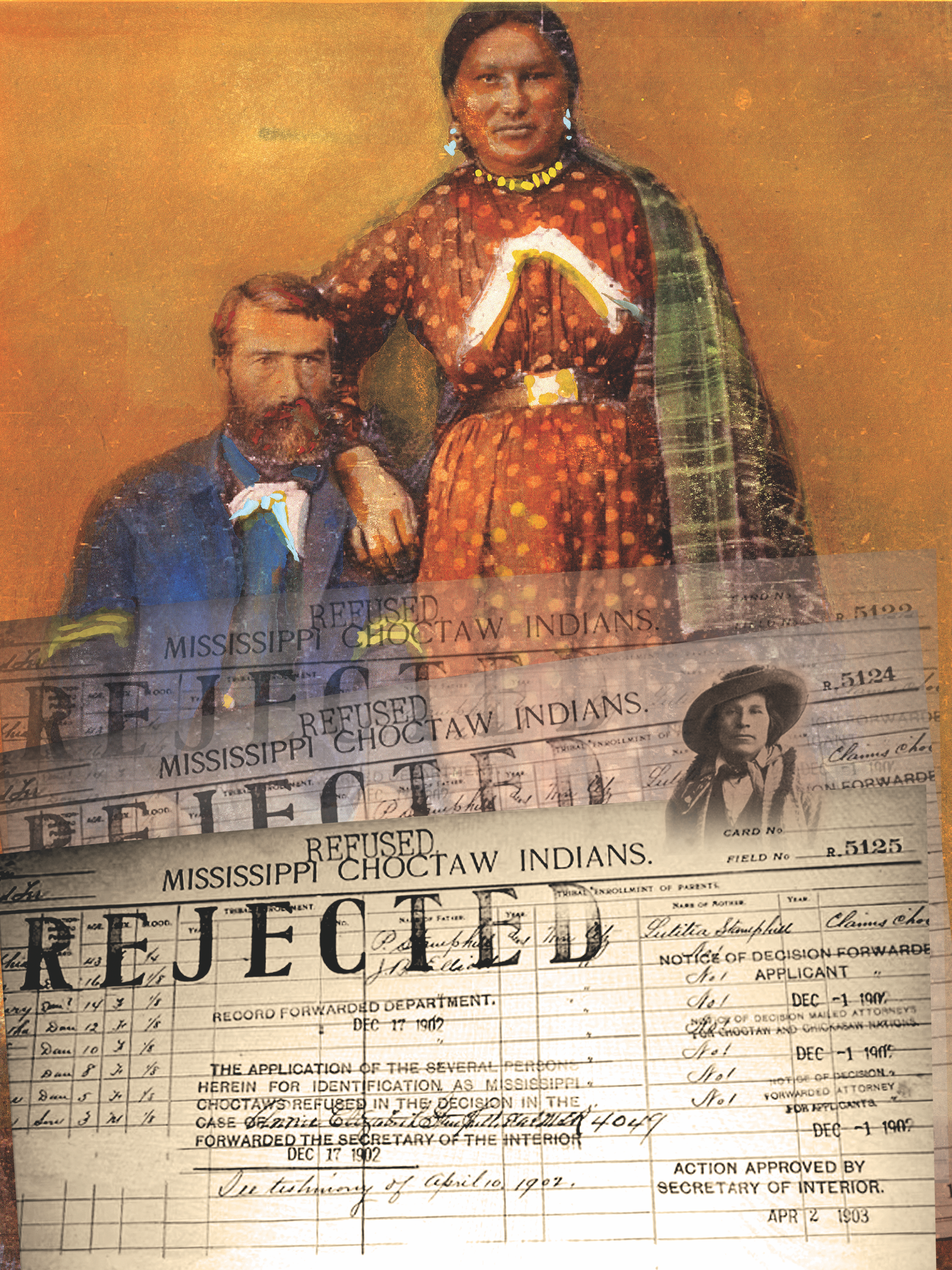

All of the Sullinger family petitioners were descendants of Soky, also known as Sophia Elizabeth, whose father, Tushkemash Tubbee and mother, Hitimer, were both full-blood Choctaw. The last name Tubbee means chief, or related to a chief, indicating an important family. Soky was full-blood Choctaw, and married a White man, James Granster Sullinger. Soky had one son, Charles, and two daughters, Lutishia and Esther, who were half-blood Choctaw.

The Sullingers lived in Missis-sippi, but then Soky moved with the Choctaw “migration” to Skullyville, established in 1833 as capitol of the Choctaw Nation, in the Indian Territory. The three children stayed with their father, James, in Mississippi, and while we do not know the true circumstances, one can theorize that the parents might believe their offspring would have a more promising future living among Whites. It is unknown when Soky moved to Skullyville, where she would live the rest of her life, dying, according to documents, “some time before the Civil War.”

At the time of her descendants’ filing, in 1896, Charles was 66. His sister, now Lutishia Stamphill, had married a White man, Pumphrett Stanfill, in 1843, and was 70. Their sister Esther was deceased, but her son, James Cleveland, was 44. To be eligible for benefits, one had to be at least 1/8th Choctaw blood. The two still-living Sullinger children were each 1/2 blood, and the late Esther’s son, James, was 1/4. Between them, Charles and Lutishia had a total of six 1/4 blood children, and the total of 1/8th blood grandchildren was 37.

While members of the other Five Civilized Tribes had to live within their Nation to apply, the Choctaw did not, and in fact more Choctaw lived in Mississippi than in the Nation, leading the Dawes Commission to open offices in Mississippi to begin processing Choctaw, who would eventually have to establish residency in the Nation to receive their allotment. Charles and Lutishia and their families had been living in the Choctaw Nation for seven years when they applied. Unfortunately, the Choctaw maintained far fewer and less complete census records than other tribes. With lack of strong evidence of tribal identity, the Dawes Commission made decisions based on how a person looked, or whether they could speak the language–particularly unfair, considering the fact that most applicants had not lived in the Nation. Undoubtedly there was some fraud. According to the Oklahoma Historical Society, only 1,457 of the 2,597 who applied were placed on the Dawes rolls.

The application for “Chas. D. Sullenger Et Al,” presented to “The United States Commission to the Five Civilized Tribes,” consisted of a history of their family descent from Soky, and the three principals’ declarations that it was all true. Also included was a notarized sworn statement from Arwichema Dixon, “a full blood Choctaw Indian and citizen of the Choctaw Nation…duly recognized and enrolled,” who had known Soky and her sister, Miami; known that Soky was recognized as a full-blood Choctaw and a tribal member; and also knew Charles and Lutishia. A sworn statement from William Martin, who was not only a recognized tribal member but, “at different times, County Clerk. Circuit Clerk, Sheriff and coal weigher of said Nation, and in August 1896 was elected representative of the San Bois County to the National Council,” swore that he knew Charles, Lutishia and James, and had known Soky, his Grandmother Miami’s sister, and narrated the same family history. All of these statements and the application were executed on September 2, 1896. Application was made in the month of September–the specific date is not noted–and the court had 30 days to deny the application, or it would be automatically approved. The fact that there had been no ruling by October 30th should have meant that the petitioners had been approved. Instead, on December 2, 1896, at least 63 days after the filing. The Dawes Commission denied their application.

In their appeal, dated January 23, 1897, the applicants’ attorneys noted six errors in legal procedure: (1) allowing the Choctaw Nation to file their answer after the 30-day limit, (2) allowing them to file without notification, (3) not allowing the petitioners to inspect the answer after it was filed, (4) not allowing petitioners to answer and file additional proofs, (5) not allowing petitioners to be present at the trial, or to have the trial held before a jury. And finally, (6) “That said judgement is contrary to law and against the weight of the testimony.”

Among the interesting additions in the appeal was the testimony of 72-year-old Pumphrett Stanfill, Lutishia’s husband. “We were married in 1843… I became acquainted with her when she was about 8 years old. She was then living on the Choctaw settlement in the state of Mississippi with her father and mother…in the early part of 1833… My wife’s mother disappeared from Missis-sippi about the year 1836, when a number of the Choctaws left Mississippi for the Indian Territory.”

In response, the Choctaw Nation simply stated that the Sullengers were not Choctaw, had never before represented themselves as Choctaw, and if they had any Choctaw blood, it was less than 1/8.

On August 24, 1897, “…the court after hearing all of the evidence of both plaintiffs and defendant and argument of counsel doth find that the plaintiffs…are citizens by blood of the Choctaw Nation and Tribe of Indians and as such are entitled to all of the rights, privileges, immunities and benefits as citizens by blood of the Choctaw Nation or Tribe of Indians in the Indian Territory.” The plaintiffs were even awarded court costs. That should have been the end of it, twice. But it wasn’t.

The bad news: on the back of a scrap of paper, unsigned, undated, scrawled in pencil, are these words: “Arwichema Dixon near Lodi Jud (?) near residence of Amos Henry—Told Gov McCurtain that Cleveland (?) Martin came to her & offered her $60 to sign paper—she got a pair of shoes & something else—this Mr. McCurtain learned in 1897.” It’s unclear, but seems to be an accusation of fraud. McCurtain was the then-governor of the Choctaw Nation, and highly respected. But who said Arwichema Dixon said this? Whoever was repeating the story didn’t know enough to say whether they were accusing James Cleveland or William Martin.

An even bigger problem was the law firm of Mansfield, McMurray & Cornish, hired to represent the Choctaw Nation as well as the Chickasaw Nation, whose Citizenship Courts would be combined, creating a new excuse to rehear already-settled cases. M, M & C certainly had a vested interest in denying citizenship: the headline in the Dec. 14, 1904 Oklahoma State Capitol reads, “$750,000 FOR THEIR SERVICES—Big Fee Allowed Mansfield, McMurray & Cornish.

FIXED BY THE COURT. Contract Provided for Contingent Fee of Nine Percent of the Value of Allotments.” Their fee would be $27,089,000 in today’s dollars. In fact, The Daily Ardmoreite of July 24, 1904, notes, the law firm “may talk all they please about all they have saved the Chickasaw Nation, but …the great issue in this election … is the enormous fee of $1,728,000.” That’s $62,450,000 today. In the May 12, 1910 Vinita Leader, “Just before Oklahoma was admitted to statehood McMurray, Mansfield and Cornish…were under indictment for obtaining money from the Indians improperly, in addition to the enormous fee of $750,000.”

M, M & C took a new tactic to deny citizenship. Instead of concentrating on blood, they focused on applicant’s knowledge of an 1830 treaty. Choctaw who stayed in Mississippi would receive land if they informed U.S. Indian Agent Col. William Ward of their desire to stay and become U.S. citizens. But as one of the firm’s own lawyers explained to the court, “A good many Indians did this whose names Col. Ward failed to put upon his register, known as Ward’s Register. His failure to put them down caused many Indians who had land in Mississippi upon which they had improvement to lose both for they were taken from them by the Government and sold at Public Land Sale.”

The questioning of Lutishia’s 39-year-old son Charles, who was enrolled, and was being asked about his cousin, Latimer Cleveland, is typical. “Q: And do you think because you were enrolled… and his brother were enrolled by judgement of the United States Court that it has any bearing on this application that he has made to be identified as a Mississippi Choctaw? A: It looks like it would be… Q: Do you know positively how much Choctaw blood he has? A: No, sir. Q: His hair is not black, is it? A: No sir, brown. Q: Do you know whether the ancestors of Latimer K. Cleveland complied with article fourteen of the treaty of 1830? A: No sir, I don’t know. I wasn’t born.”

In March of 1904, before the Choctaw and Chickasaw Citizen-

ship Court, another hearing was held. Having trouble getting witnesses to appear, and feeling their previous work was sufficient, the attorneys for the Sullengers merely reintroduced their affidavits from the earlier cases. It was a mistake. If all of the previous witnesses had died, the Sullengers might have won. But as Associate Judge Foote explained in his opinion, the evidence from the complainants consisted of ex parte affidavits, which means that they are given by one side, without the other side having the opportunity to cross-examine. “No proof was made before us that any of the parties making these ex parte affidavits were then dead or beyond the jurisdiction of this court, so that they are incompetent as evidence. None of those making said ex parte affidavits were produced to testify before us.” On March 28, 1904, the court ruled “…the plaintiffs…be denied, and that they be declared not citizens of the Choctaw Nation, and not entitled to enrollment as such citizens, and not be entitled to any rights whatever flowing therefrom.” And another 9 percent flowed to Mansfield, McMurray, and Cornish.

Fast-forward to the 1970s. The Supreme Court had confirmed that Indian Reservations were their own nations, and enterprising tribes began building casinos on their land. Few of us would begrudge them making some easy money. As You’re No Indian director Ryan Flynn puts it, “I looked at the casinos, in a way, like reparations. They’re living in such impoverished locations. Give them a business that can bring wealth and a seat at the table politically.” Many worried that organized crime would move in, pay the naïve Natives a pittance, and steal the business out from under them. That’s not what happened.

Seven years ago, Flynn was in Egypt, “building fancy maps for the archeologists that worked on the Giza Plateau.” One night he got curious, “about how much an Indigenous person gets from their casinos. I start Googling, and it turns out that it varies wildly from tribe to tribe.

“Sometimes it’s zero, sometimes it’s over a hundred thousand dollars a month. And that’s where I came across these allegations of wrongful disenrollment.”

And that’s the subject of his documentary. It’s a jaw-droppingly simple concept. Casino profits are divided among tribal members. If you kick out half of your members, the remaining members double the size of their cut. The usual approach is to simply claim that some member of the tribe is really an outsider. There is no burden of proof because the accusers are also the ones who evaluate the evidence. And if they decide an ancestor isn’t really a member, all of their descendants are out as well. “One family, they had all their paperwork; they had all the evidence. They had DNA evidence that they got by being forced to exhume bodies, passed the DNA test. And they were still disenrolled.”

And before you say, that has to be illegal, remember, the tribes are their own nations. “The state and federal governments don’t have jurisdiction, and the people that kicked you out are bene-fiting. It’s conducted by judges that should recuse themselves because they’re benefiting financially from these disenrollments.”

The Nooksack Indians of Washington State, with their Nooksack Northwood Casino, are a textbook example of the problem. “Many of the people who were disenrolled had rent-to-own housing programs. So after 15 years of rent payments, they were going to get the deeds to their homes. And the tribe kicked out 306 people just before they were going to get the deeds. There was an Appellate Court that the tribe agreed to be a part of. The 306 went to the Appellate Court, won, and then the Nooksack Tribal Council declared themselves Supreme Court Justices and overturned the Appellate Court. There is no due process. And that’s why the UN stepped in.” Sadly, the United Nations has no more authority than the United States in tribal matters. Whoever is in charge makes up their own rules, and changes them at will.

How many people have been disenrolled? “About 11,000 that were in a tribe and they were kicked out. But what about enrollment moratorium, people that are rightful members that can’t get in because they didn’t file their paperwork by a specific date. Why would you not let rightful members in if it’s not about resources?” How many tribes are disenrolling members? “Our estimates are between 15 and 20 percent. You know, it’s not necessarily just about casinos. Sometimes it can be about grant money, sometimes it can be about housing, but the vast majority are tribes with casinos. In one case, a tribe was trying to grow because they would get more monies from government programs. So then they got the casino, and to date about half of that tribe has been disenrolled.”

Getting the word out has not been easy. You’re No Indian was to premiere in January at the Palm Springs International Film Festival. “We sold out both of our screenings, and weeks before our premier, they told us there was a scheduling issue. For both screenings. There are significant tribes with casinos in the area, one of which is a major sponsor of the festival. And we were kicked out without explanation.” Instead it premiered in June, in Los Angeles, at the Dances With Film Festival.

The fascinating, infuriating documentary is narrated by Native actress Tantoo Cardinal, and she and Wes Studi are executive producers, and Natives who are extremely concerned about the disenrollment issue.

What happens to a person who is disenrolled? “Imagine getting disenrolled from the United States. You’re no longer a citizen. Where do I live? What do I do? But then a deeper question is, who am I? This is my language. I have my community. It’s a profound loss of identity. We’ve seen people that are the last living language speakers get disenrolled from the tribe because they stood up for disenrolled people.”

To find out where you can see You’re No Indian, visit the official website here: https://www.yourenoindian.com/