In the spring of 1877, a government scout named Jack Dunn was winding his way down what later became known as Tombstone Canyon in southeastern Arizona in pursuit of hostile Apache. Dunn, scouting for Company C. 6th Cavalry under the command of Lt. J.A. “Tony” Rucker, was searching for a spring in the vicinity of Castle Rock when he noticed an interesting outcropping and stopped to investigate. As was common on the campaign trail, soldiers spent one eye looking for Apache and the other looking for mineral. Dunn collected some specimens and showed them to Lt. Rucker and a packer named Ted Byrne. They couldn’t have known it at the time, but this outcropping in an isolated little canyon not far from the Mexican border would become known as the “Glory Hole” and the Warren Mining District in which it was located was destined to become one of the richest copper-bearing areas in the world.

Back at Ft. Bowie, Dunn recorded his name along with Lt. Rucker and Byrne. The claim, named the Rucker was filed on August 2nd, 1877. Dunn, Rucker and Byrne were too busy campaigning to stake out their claims so they prevailed upon a local character named George Warren. They also made him a partner and grubstaked him with supplies and a couple of burros. While on his way to the south end of the Mule Mountains, Warren stopped at Camp Detachment in the foothills of the Huachuca Mountains to have a few drinks with some prospectors. When he told them about Dunn’s strike they decided to go along with him and on September 27th, 1877 they located the Mercy Mine on the site of Dunn’s discovery. Rucker, Byrne and Dunn’s names were omitted as they were from several other claims Warren filed in the area including the Halcro on December 14th, 1877.

Several months later, on July 11th, 1878, Lt. Rucker drowned in a flash flood, trying to save the life of a comrade, in the canyon that today bears his name. Camp Rucker was established as is Rucker Lake in the southern Chiricahua Mountains. Dunn left the Army in 1885 and retired to a more sedentary life in the east. He seldom broached the subject of being swindled out of a fortune by his erstwhile partner.

During his forty-two years on the frontier, George Warren had led an ill-starred life. His mother died when he was an infant. A maiden aunt raised him until he was old enough to go live with his father. Soon after father and son re-united they were attacked by a band of Apache and his father was killed. The ten-year-old youngster was wounded and taken captive. For the next eighteen months he was subjected to the abuse of his captors. Then he was sold to some rough-hewn prospectors for fifteen pounds of sugar.

Not surprisingly, George developed a taste for whiskey and became a heavy drinker. He was also a quarrelsome guy, something that got him shot in the neck during a duel. In other gunfights he took a bullet in the arm and another in the leg.

On July 3rd, 1880 George was celebrating in the mill town of Charleston with a friend, George Adkins. They got into a friendly argument whether a man could outrun a horse over a distance of a hundred yards. Warren knew he couldn’t outrun a horse on a straight away but he could reverse directions faster and that’s how he planned to win the wager. George was also counting on his experiences with the Apache had made him a formidable runner

Warren wagered his one-ninth share in the Halcro Mine and Adkins wagered his horse. Warren might have won the bet if he’d proposed a shorter race. He planted the stake at 50 yards from the start.

The whole town of Charleston turned out to see George race a horse. Bets were placed and the race was on. He led to the turn but on home stretch the horse left him in the dust. George had bet and lost his share in the Halcro mine. It would soon become the fabulous Copper Queen, eventually producing some thirteen million dollars in gold, silver and copper. It’s estimated his share would be worth twenty million dollars today.

Less than a year later, in May, 1881 George Adkins asked the Cochise County probate judge to declare his old friend insane. Warren’s other claims were sold at public auction. He went to Mexico determined to make another strike but wound up selling himself for peonage to pay off a forty dollar debt. When Bisbee Judge G. H. Berry learned of the situation he paid off the debt and brought George home. After that he took menial jobs sweeping out saloons and cleaning cuspidors in exchanged for whiskey.

He died penniless on February 13th, 1893 and was buried in a pauper’s grave. He was forgotten for several years until 1914 the Elk’s Lodge in Bisbee moved his body to a more prominent location and erected a monument to honor him.

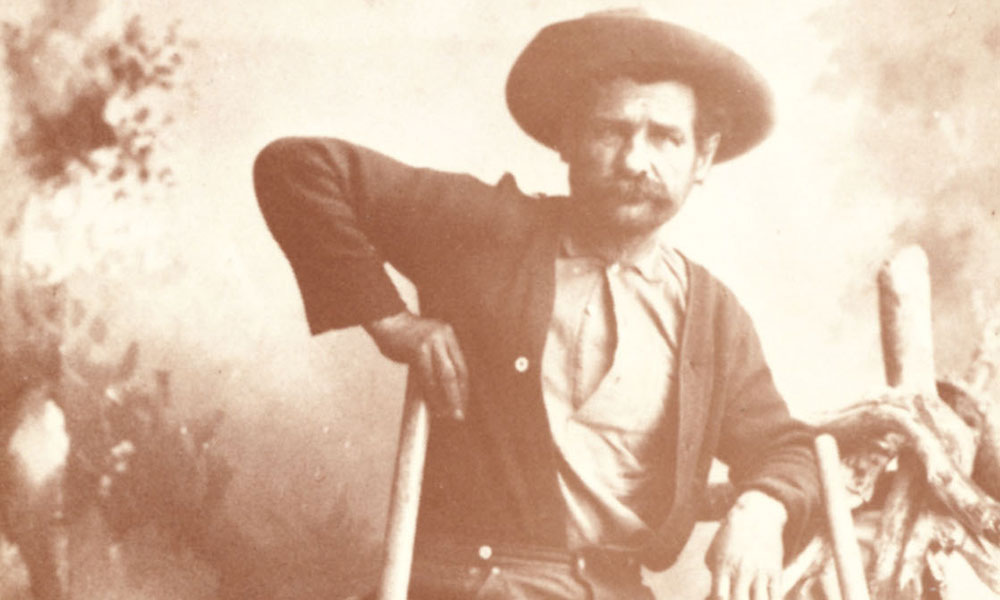

George did manage to get a town named for him and a mining district. Today he’s remembered as the “Father of the Mining Camp.” His picture was taken in 1880 by Tombstone photographer C.S. Fly, who used to visit the town with his camera on payday. Later it was hung in the lobby of the Bank of Bisbee where it caught the eye of William Brophy who was attending a meeting in the bank. Arizona was about to be granted statehood and the state seal was being planned. It was noted the design had everything except a person. Brophy looked at Warren’s photo and decided he would be the perfect representation for the new state. And that’s how George Warren landed on Arizona’s State Seal.

https://truewestmagazine.com/john-hance-grand-canyons-windjammer-2/