— Courtesy Library of Congress —

On the night of August 14, 1891, Toribio Pastrano, a 35-year-old Presidio County deputy sheriff strode into a Mexican fandango in search of an elusive outlaw named Antonio Carrasco. Pastrano reportedly had evidence that linked Carrasco with the murder of Texas Ranger Charles Fusselman in El Paso County the year before. Though other Texas lawmen had already attributed Fusselman’s slaying to a gang of cutthroats who operated out of the swampy thickets along the Rio Grande near El Paso, Pastrano was determined to bring in Carrasco, all the same.

According to the Austin Weekly Statesman, as Pastrano made his way through the couples who waltzed to the “tinkling of guitars,” he spotted his quarry at the far end of the room. If newspaper reports are to be believed, Carrasco would have been a hard man to miss in any crowd. “He was dressed from head to foot in snow white duck and around his waist was a broad red sash, from which protruded the handle of a revolver,” the Statesman reported.

As a man who lived most of his life on the dodge, Carrasco knew a lawman when he saw one and he eyed Pastrano carefully as the officer approached. He called out to him, “My friend, you are an officer, and wish to arrest me. Very well.” Then, before Pastrano even had a chance to respond, Carrasco whipped out his six-shooter and shot the lawman through the head, just above the right eye, killing him instantly. “Backing out of the room Carrasco, with leveled revolver, defied any man to arrest him, and springing upon his horse plunged into the river,” the Statesman reported. “He reached the opposite bank and disappeared.”

Though seldom mentioned in the histories of borderlands outlaws written by American authors, Antonio Carrasco’s life story reads like the fantasy of a Hollywood filmmaker, a blend of myth and deadly reality worthy of one of the corridos, or folk songs, that became so popular during the Mexican Revolution. As it is, separating fact from fiction in the story of Carrasco is no easy task and very little is known of his early life.

— Courtesy of the El Paso Public Library, Border Heritage Center —

One of three brothers who would make names for themselves as West Texas outlaws, Carrasco came from a large family and was the son of Jose Faustino Carrasco Mercado and his wife Maria Tiburcia Cayetana Torres Baeza. According to legend, Carrasco’s father was killed by the Rurales, President Porfirio Diaz’s fearsome gray-jacketed enforcers. In 1891, a Confederate veteran named Frank Benairs claimed that while traveling south towards Central America after the Civil War, he and his servant heard stories of a teenaged Carrasco, who was already making a name for himself. Benairs later told friends in San Antonio that both of Carrasco’s parents had been murdered by soldiers and a sister had been carried away. In Benairs’ account, Carrasco appealed to the authorities for help in capturing the officer responsible but had been turned away. Carrasco had finally taken matters into his own hands. “Within the first year his enemy’s father and mother were taken to the mountains,” Benairs recalled, “tortured and their heads placed on stakes in the highway; his young sister was murdered and her body thrown into the street with a dagger pinning a letter to her breast; finally the suspected officer himself was captured, taken to the mountains, tortured into confession, and then slowly into death.”

Though Benairs’ story seems highly suspect, the legend of Antonio Carrasco is similar to that of other bandits, including Joaquin Murrieta in California and Carrasco’s more famous contemporary Pancho Villa, whose own life as an outlaw allegedly began at the age of 16 when he shot a man who tried to take his sister as a concubine. All legends aside, Carrasco, “that prince of devils,” in the words of the Detroit Free Press, did in fact ride at the head of a band of outlaws, one of several that prowled a section of the Rio Grande Valley of West Texas known as “The Bloody Peninsula,” a deadly 60-mile stretch of lower Presidio County. Throughout his criminal career, Carrasco stole horses, extorted ranchers, broke into houses and, according to the Statesman, by the time he killed Pastrano, had killed eight other men in shootouts.

— Courtesy Western History Collections, University of Oklahoma Libraries, Rose Collection, Image #1441 —

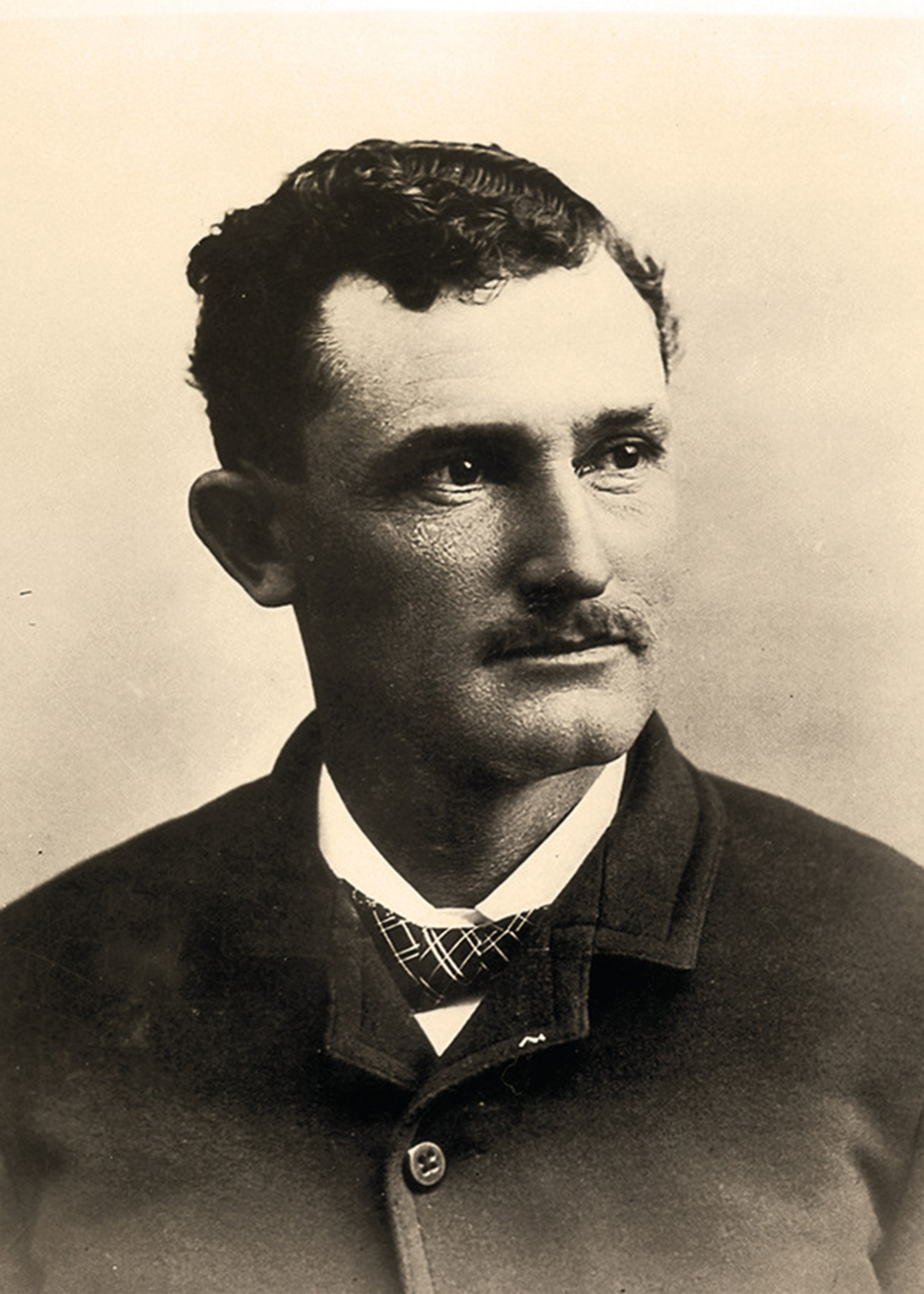

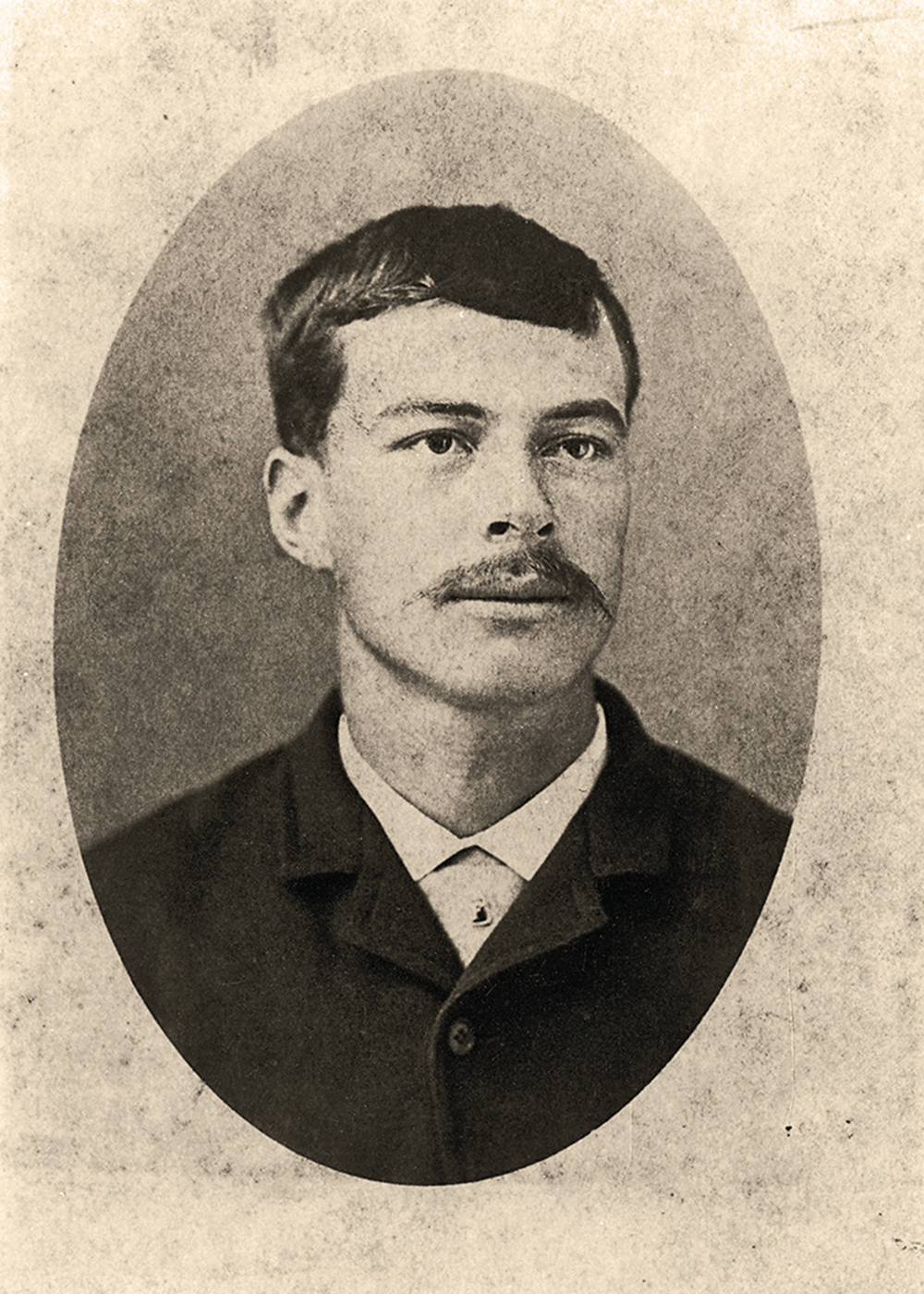

Today, Carrasco’s brothers Matilde and Florencio are somewhat better known, largely because they died facing the guns of some of the most legendary Rangers in Texas. On the night of January 12, 1892, Texas Rangers John R. Hughes and Alonzo “Lon” Oden set out to arrest Matilde Carrasco and two companions for stealing ore from the mines at Shafter, Texas. With help from a former Ranger-turned-informant named Ernest “Diamond Dick” St. Leon, Hughes and Oden prepared an ambush, and when the outlaws refused to surrender, they cut down Matilde Carrasco’s associates with shotgun blasts. Before he could escape, St. Leon brought Carrasco down with a fatal shot to the head.

That June, Hughes, Oden and another Ranger were on the hunt for a well-known fugitive when they had a chance run-in with Florencio Carrasco and two other bandits. In the shootout that followed, Florencio Carrasco was killed.

Somehow, either because he was too elusive or too lucky, Antonio Carrasco managed to avoid the bloody fate of his brothers. In 1895, a man named Antonio Carrasco was arrested for horse theft and received a five-year prison sentence, though it’s unclear if this is the same man who killed Toribio Pastrano. In any case, he was never called to answer for the murder of the Presidio County lawman, and in the summer of 1898, this Carrasco escaped from custody while serving as a prison trusty.

Then, in the spring of 1900, the El Paso Herald reported that Antonio Carrasco had been arrested by Mexican authorities in Juarez. According to the Herald, Carrasco had spent time in a prison in the state of Chihuahua in the years that followed the death of Pastrano. Following his release, he had gone to Juarez where he’d gotten into some trouble and landed in the local jail where he was recognized. It was reported that the sheriff of Presidio County would seek Carrasco’s extradition back to Texas, though that effort ultimately failed.

Finally, as Revolution exploded across Mexico in late 1910 and early 1911, Antonio Carrasco apparently saw an opportunity to step out of the shadows. Carrasco reportedly appealed to Col. Jose de la Cruz Sanchez to allow him to join the rebel army, fighting on behalf of Francisco Madero. “You have fought the dictator Diaz for a few weeks,” Carrasco told Sanchez. “I have fought him for many years. I want to help Madero to win and get a pardon so that I may quit this life of a humbled coyote.”

— Courtesy of the El Paso Public Library, Border Heritage Center —

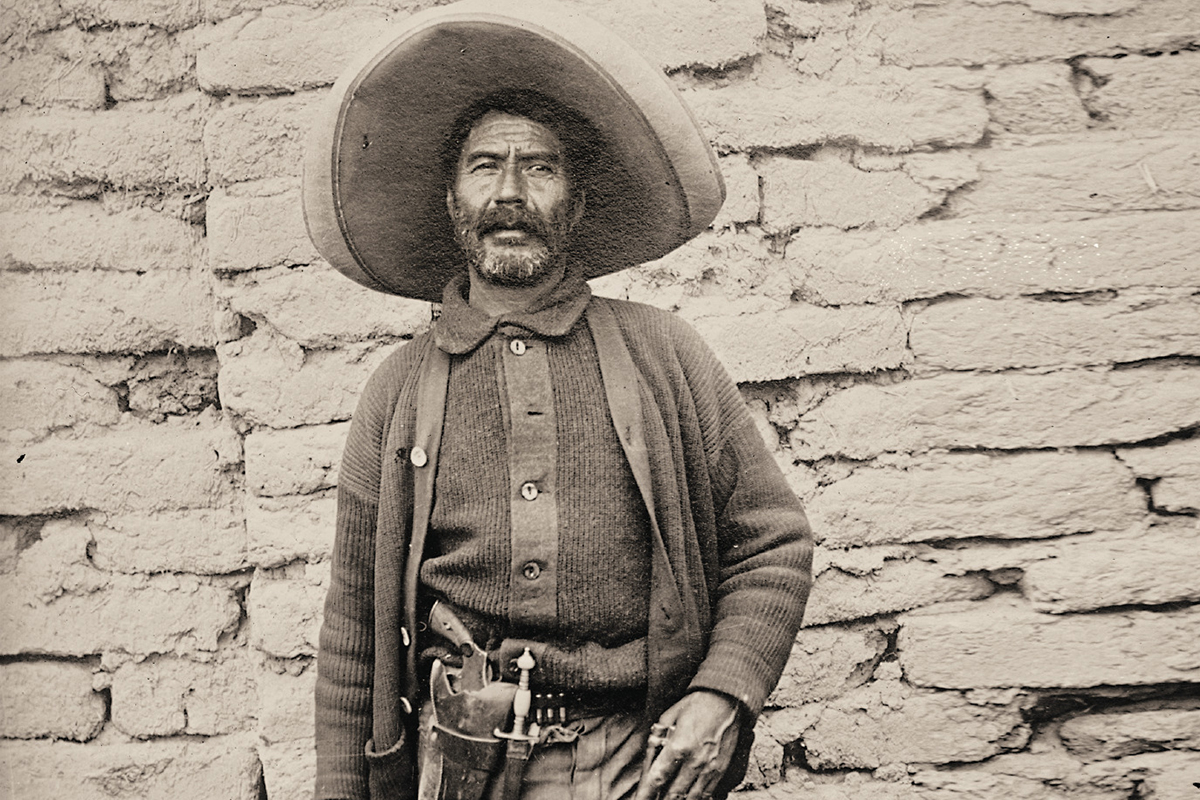

Because of Carrasco’s record and his reputation, Sanchez initially refused to allow the bandit to join the fight. Carrasco went ahead and raised his own company anyway and, according to an account later published in the Buffalo Sunday Morning News, “proceeded to wage a little private war.” It was at some point during this stage of his life that Carrasco posed for

an iconic photograph. Standing before an adobe wall, Carrasco wore an impossibly large sombrero and not one, but two sweaters. He held a Model 1894 Winchester carbine, and around his waist is a cartridge belt, a holstered Smith and Wesson and a distinctive knife with an ornate ivory handle. Carrasco’s face carried a salt-and-pepper beard and deep creases along his forehead and around a pair of eyes that seem to look past the camera with a gaze that suggested they’d seen many battles. Eventually, Sanchez had a change of heart and in early part of 1911 he allowed Carrasco and his band of 100 men to formally join the revolutionary army.

In late February of 1911, the Herald reported that Carrasco, acting “under superior orders,” led a raid on the small village of San Antonio across the Rio Grande from Candelaria, Texas. The following month, Carrasco and his men participated in the battle against President Diaz’s troops at Ojinaga. This fighting would unfold within view of the town of Presidio, Texas, where US troops and American civilians would be provided with a front row seat to the unfolding Mexican drama. According to the Boston Globe, one American woman hosted a “battle tea” on the roof of her house so that her guests could enjoy refreshments while watching the battle.

Carrasco’s recent reinforcement of Sanchez’s army was widely reported in American newspapers, though it seems that Carrasco had quickly grown tired of “fighting without the reward of loot” and failed to follow orders when assigned the critical mission to cut off enemy lines of communication. He was also later accused of having sent letters to General Gonzalo Luque, commander of the federal garrison at Ojinaga, that provided the enemy officer with important intelligence on the rebel army’s battle plans. In addition to Carrasco’s alleged duplicity, the Buffalo Sunday Morning News later reported that he and his men also engaged in violent criminal behavior while serving with Sanchez’s forces. “With a band of 35 kindred spirits he deserted his post and made a raid through the country, looting several ranches and ending at the little town of San Antonio, where a mescal distillery was located,” the Sunday Morning News declared. “Here he indulged himself in a protracted carouse and wantonly killed an old man who was unarmed and helpless.” On April 4, 1911, Carrasco was court-martialed for treason and sentenced to death.

When Carrasco learned that he would be meet his own fate the next morning, the old bandit was reportedly disappointed. “Why not tonight?” Carrasco asked. “I might not sleep well.” According to an account published in 1913, many of Carrasco’s fellow insurrectos were uneasy about executing the well-known bandit and feared retribution by Carrasco’s many friends and relatives. Lots were finally drawn to decide who would serve on the firing squad and the executioners were placed under the command of Frank “El Diablo” McCombs, an American soldier of fortune and, according to the Sunday Morning Times, “a man of much experience in military killing.”

— Texas Ranger Hall of Fame and Museum, Waco, Texas —

On April 5, 1911, Carrasco was marched up a dry arroyo several hundred yards from the insurgent camp. “This spot will do as well as any,” Carrasco told his executioners and then asked permission to smoke a cigarette as McCombs formed his men into a line. “There is one request I want to make,” Carrasco told the firing squad. “Please shoot at my heart. I don’t want my face all torn up.” A few moments later, Carrasco sensed the uneasiness in one of the men about to kill him and sneered angrily. “What are you trembling for?” Carrasco asked him. “I’m the fellow that’s going to die. If I had a chance to kill all of you, I’d be glad. I wouldn’t shake.”

With the cigarette still dangling from his lips, Carrasco opened his coat and ordered, “Aim here at my heart. Are you all ready? Then—fire.” Three of the six executioners then opened fire with their Winchesters and Mausers. Struck in the chest, Carrasco tumbled back onto the ground, his cigarette falling onto the front of his shirt. McCombs coolly stepped over to the dead bandit and flicked the burning stub away with his hand. “Another bad man gone to hell,” McCombs said, then turned and walked back to camp.

Samuel K. Dolan is the author of Cowboys and Gangsters: Stories of an Untamed Southwest.