On a balmy September morning in the little valley east of the Mimbres Mountains in southwest New Mexico, seventeen-year-old Martin McKinn and his eleven-year-old brother Santiago were herding cattle near their ranch on Gallina Creek, a tributary to the Mimbres River. The two McKinn boys were the sons of an Irish father John and their Mexican mother, Luceria. That morning their father had gone to Las Cruces with some neighbors to purchase supplies.

It was about eleven o’clock on September 11th and the boys were taking a break for lunch. Martin was sitting beneath a shade tree reading a book and Santiago had gone down to play in the creek. Suddenly, Santiago heard a rifle shot then he saw an Apache he later identified as Geronimo, run up and crush Martin’s head with a rock. Geronimo then removed his brother’s shirt and coat and put them on. Santiago tried to run away but they caught him.

Searchers found later Martin’s body but Santiago was missing, something that gave them hope that he might be a captive.

Geronimo asked him questions in Spanish about the number of men and horses in the area but the youngster was too traumatized to answer. They put him on the back of a horse and rode towards the Mimbres River.

Over the past few days the wily, sixty-three Apache shaman and his seven followers had been on a murderous raid, killing and pillaging along the valley east of the Mimbres Mountains. Before slipping into the Mogollon Mountains they had ruthlessly slaughtered five men. A Mrs. Allen and her three children escaped into the brush after her dog lunged at one of the warriors, distracting them momentarily. The warriors could have easily run them down but Geronimo decided instead to loot the cabin for much-needed supplies. The war chief later said he knew the murder of a mother and three children would had created a worse outrage than the killings thus far. Mrs. Allen and her children then walked some eight miles to a sawmill operated by soldiers from nearby Fort Bayard.

By September 15th the Apache band had managed to elude cavalry troops from Ft. Bayard and local militia, taking refuge high in the Mogollon Mountain wilderness an area that was described as a “natural fortress.”

At the time, Geronimo had no idea his bloody raid had stirred up a hornet’s nest in both Washington and Mexico. Henceforth, Mexico would cooperate with U.S. troops operating south of the border and the Army was given full authority over the San Carlos Reservation.

In early October the bands of Geronimo, Naiche, Nana and Chihuahua slipped past the soldiers guarding the border and made their way into Mexico’s Sierra Nevada. Santiago McKinn was still with Geronimo’s band. Over the next few weeks the Apache bands continuing raiding the Mexican settlements. A force commanded by Captain Emmett Crawford, U.S. cavalry and Apache scouts had crossed into Mexico and had been in constant pursuit.

After months of hard campaigning, on the morning of January 10th, 1886 the Apache scouts surprised Geronimo’s camp and after a short battle the old shaman had enough and threw in the towel. He could elude the Army but the Apache scouts had found his most formidable sanctuary. He was ready to meet with General Crook to discuss surrendering.

On the morning of January 15th all the chiefs, Naiche, Chihuahua and Nana agreed to meet with General Crook to surrender in one month at a place called Canyon de los Embudos. The meeting took place on March 25th, 1886.

It was the waning days of the so-called Geronimo Campaign. These were the last holdouts of a long war that began in early 1861. The great chiefs, Mangas Colorados, Cochise and Victorio were gone and no other leader had risen who could being the different factions together.

On the morning of March 26th, Tombstone photographer C.S. Fly who was traveling with Crook, got Geronimo’s permission to take photographs. While taking pictures of some youngsters Fly discovered one of them was a white boy.

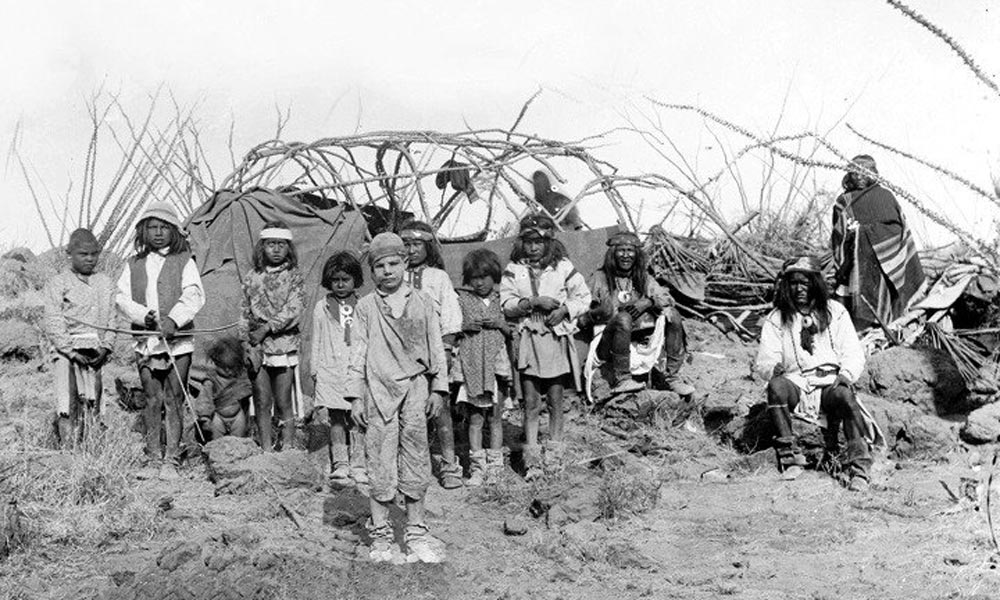

Apparently Santiago had been well-treated by the Apache and during the six months he lived with them he assimilated to their lifestyle and became fluent in their language.

Captain John Bourke, Crook’s Aide de Camp, would later write: “A group of young boys raged together freely and safely around; one of them seemed to be of Irish and Mexican descent. After a little persuasion, he told …… that his name was Santiago Mackin (sic) and he had been kidnapped in Mimbres, New Mexico; of his young companions, he seemed to be treated kindly, and no one tried to stop our conversation … Beyond its smart looks which made it clear that he had fully understood everything we told him in Spanish and English, he took no further notice of us.”

Despite coaxing, Santiago refused to leave the Apache camp with any American. On April 6th, Chihuahua brought the boy in and gave him to Crook but the lad, “acting like a wild animal in a trap,” insisted he wanted to remain with the Apache. The soldiers tried to persuade him but he would have none of it, defiantly refusing to speak any language except Apache. Young Santiago had become “Indianized.”

The talks on March 28th seemed to be going well until that evening some local whiskey peddlers fearing an end of the war would seriously hamper their business, got Geronimo and his warriors drunk and told them they would be killed upon their arrival in Arizona. That night Geronimo broke his word and bolted once again.

The Apache from other bands along with Santiago remained in camp. They were taken to Fort Bowie where on April 2nd, they formally surrendered.

At Bowie Station, east of Willcox, Santiago, wearing only a “gee-string,” got on the train with the others headed for the prison camps in Florida. When the train stopped in Deming, New Mexico his parents picked him up, got him outfitted in a local mercantile store and took him home.

Santiago grew to adulthood in Grant County, married Victoria Villanueva and had four children and eventually grandchildren. The 1930 census shows him living in Phoenix. According to family members Santiago died in the 1950s in Phoenix.