Gila City disintegrated fast. The ruins proved inspiring to some and portentous for others.

Shortly after Christmas in 1863, a party of approximately 109 men made camp along the banks of the Gila River amidst a melancholy scene. They were lying atop the ruins of what was, barely 10 years earlier, supposed to have become the most fabulous city of the interior Southwest. But all that was left, according to one member of their party, was “three chimneys and a coyote.”

On that winter evening, amid the rubble and desolation, J. Ross Browne looked out at what he described as “a very pretty place, encircled in the rear by volcanic hills and mountains, and pleasantly overlooking the bend of the river, with its sand-flats, arrow-weeds, and cotton-

woods in front.”

The town of Gila City, whose ruins Browne was now contemplating, had already foreseen the oncoming rush and provided a warning of sorts. It blossomed, flourished and died in the space of 10 years, and became Arizona’s first real boomtown and Arizona’s first true ghost town almost in the same breath. This hopeful gold mining settlement had succumbed to the fatal combination of mineral exhaustion and natural disaster—a common twin punch that provided knockout blows to hundreds of would-be Shangri-las across the Southwest in the coming years, leaving only scattered wood beams and empty brick shells where once dozens and dozens of gamblers, merchants, miners and barmen had plied their trade. But Gila City beat them all in the chronology of abandonment, setting the Darwinist pattern for the hurry-harry settlement of what was shortly to become the Territory of Arizona.

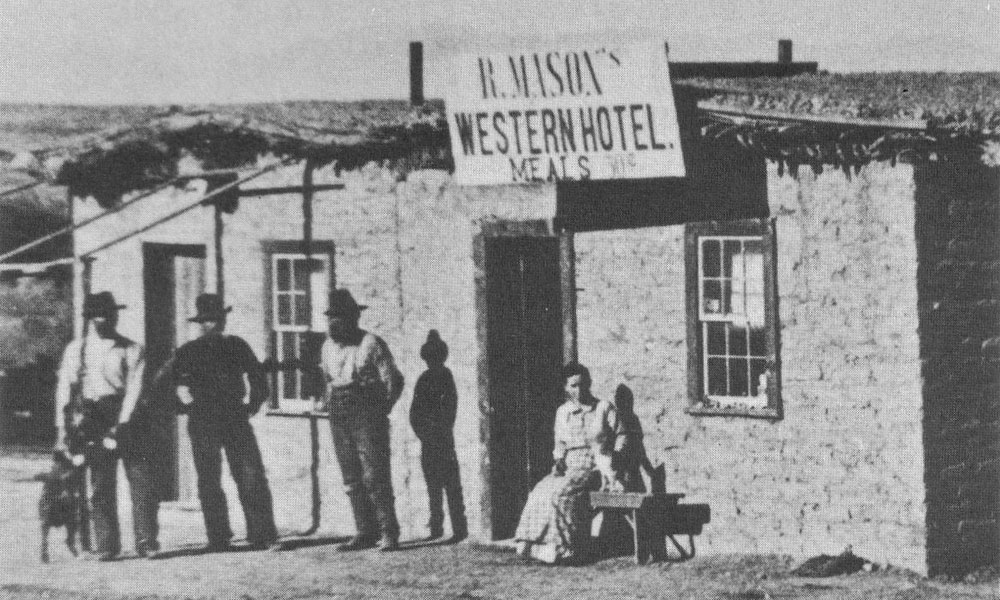

“At one time over a thousand hardy adventurers were prospecting the gulches and canons in this vicinity,” Browne wrote later in his book Adventures in the Apache Country. “The earth was turned inside out. Rumors of extraordinary discoveries flew on the wings of the wind in every direction. Enterprising men hurried to the spot with barrels of whiskey and billiard tables; Jews came with ready-made clothing and fancy wares; traders crowded in with wagon-loads of pork and beans; gamblers with cards and monte tables. There was everything in Gila City except a church and a jail which were accounted barbarisms by the mass of the population. When the city was built, bar rooms and billiard saloons opened, Monte tables were established and all accommodations for civilized society placed upon a firm basis.”

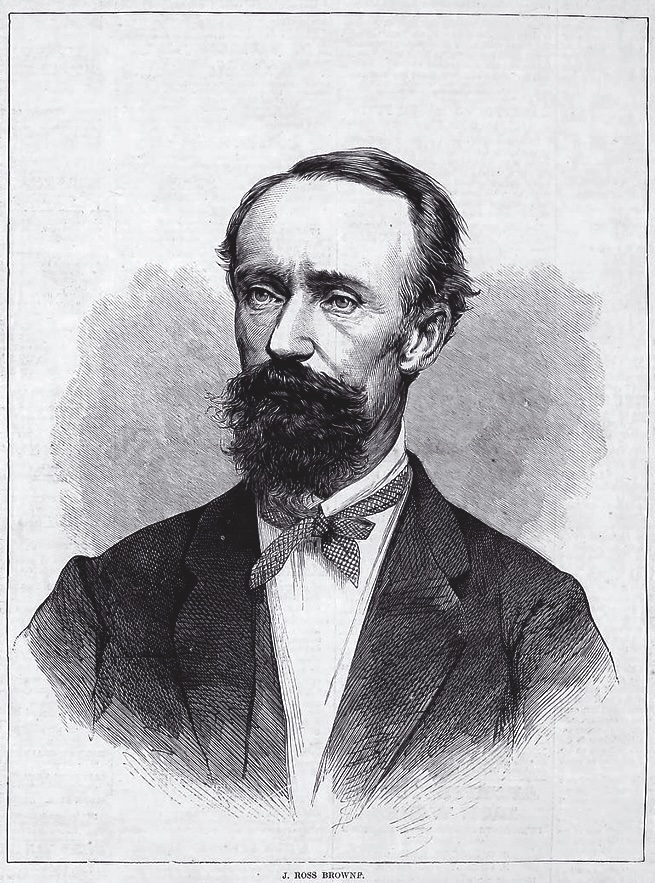

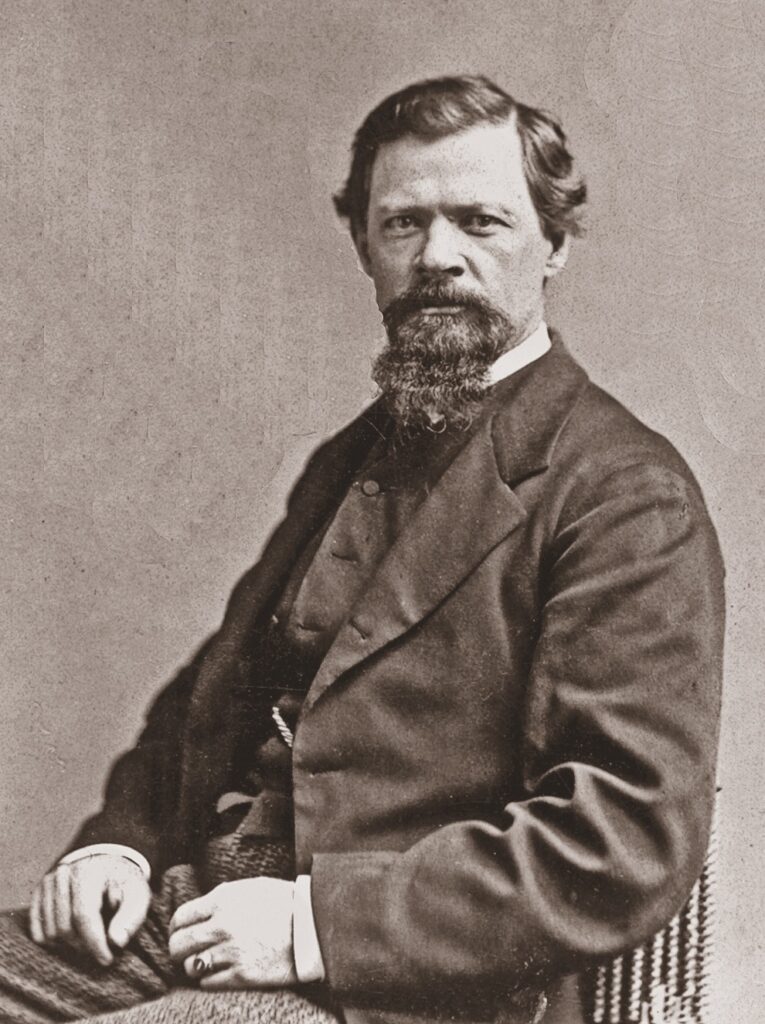

By this time, Browne was a writer of some national renown. The son of an irascible politician from the Irish town of Beggarsbush, he had immigrated to Kentucky in 1841 after his father found himself on the wrong side of the British authorities. Browne had spent his youth making journeys down the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, and after a job writing about politics for Congressional Report got too dull, he accepted a job investigating the desertion of U.S. Navy sailors in San Francisco who had lit out for the goldfields rather than spend another day swabbing decks. Browne earned enough money recording the debates of California’s constitutional convention to send himself around the world on reporting trips and contributing to the prestigious Harper’s New Monthly Magazine.

Etchings of a Whaling Cruise, his short 1846 book, was praised by the young travel writer Herman Melville as “a faithful picture” of what life was like aboard a commercial vessel. Later scholars concluded it certainly influenced the subject—if not the atmosphere—of Melville’s novel Moby-Dick. And if a reader detects a familiar note of dry humor and gentle Western hyperbole in Browne’s description of Gila City, it is generally agreed that his sage observational voice provided inspiration to another frontier writer who gave himself the pen name Mark Twain.

Arizona or Bust!

Browne was looking at the remnants of Gila City that night because of an accident. He had just gotten back to San Francisco from a trip to Europe when he ran into an old friend on the street—the promoter, entrepreneur and raconteur Charles Debrille Poston, who had just been appointed the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for what was shortly to become Arizona and hadn’t the slightest doubt that it was “the grand diamond” of all the unexplored places on the continent. He was leaving at 4 p.m. that very day. Would Browne like to join him?

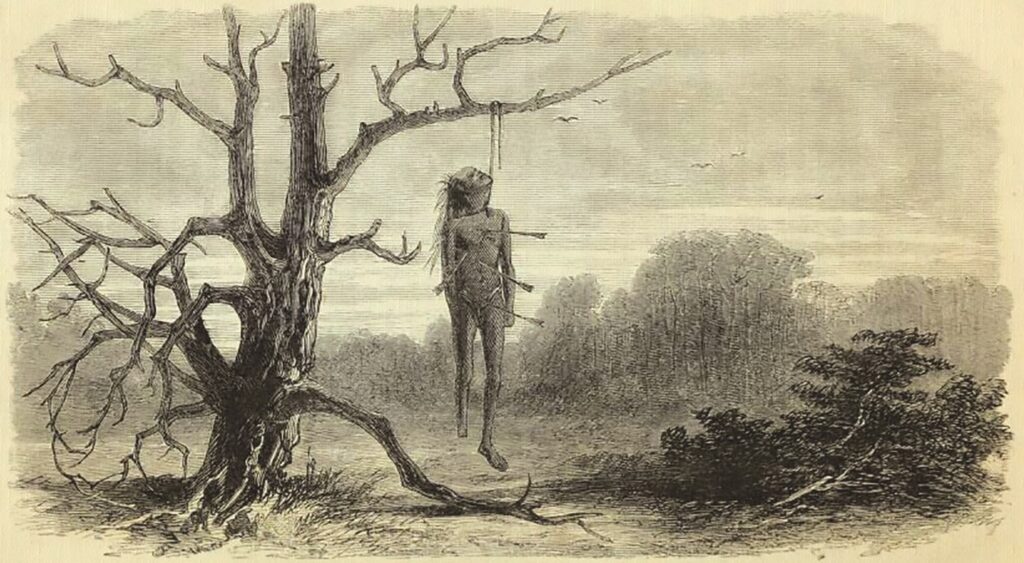

“Poston, consider me in,” said Browne, sensing a colorful story and a new book. “Should the Apaches get my scalp, you, my venerable friend and you alone, are responsible to my family and to mankind.”

Browne rushed to his home in Oakland, packed a few shirts and a plug of tobacco, kissed his startled wife, Lucy, goodbye, hugged his children and immediately sailed to Los Angeles on board the steamer Senator in the company of Poston, an Indian agent, three Pima Indians and two Catholic priests who had been commissioned by the archbishop of San Francisco to resume the masses at San Xavier del Bac south of Tucson.

Accompanied by a U.S. Army detachment, Browne, Poston and the padres bumped their way across the Mojave from L.A. to Fort Yuma, California, where they arrived in December 1863. There, Browne watched Poston distribute federal gifts to the Indians, and marveled at the mild desert temperatures.

“The climate in winter is finer than that of Italy,” he wrote. “Perhaps fastidious people might object to the temperature in summer, when the rays of the sun attain their maximum force, and the hot winds sweep in from the desert. It is said that a wicked soldier died here, and was consigned to the fiery regions below for his manifold sins; but unable to stand the rigors of the climate, sent back for his blankets.” (Twain was so amused by this local fable that he ripped it off from Browne for his later book Roughing It). The party left Fort Yuma on December 31, and soon made camp at the site of Gila City, where they found that most classic of Western landmarks: a ghost town.

Busted Bonanza

What happened? Gila City started out promisingly enough. In 1858, a veteran of the Texas War of Independence named Jacob Snively fetched up in Fort Yuma after having spent the previous nine years prospecting for gold near Mazatlán in Mexico. He led an expedition up the Gila and found placer gold near the riverbed, and more in the bluffs nearby. News spread fast. Hundreds of good-luck seekers filed claims, and they were as much an aggregate as the soil itself. As historian Jim Turner would write about early Arizona mining camps in general: “From California and all points of the globe came emigrant Frenchmen, Germans, Swiss, Irish Serbian, Jews, and every combination imaginable. History calls them Anglos, or Americans, because they came from the United States to Arizona, but the accents, clothing and customs gave the territory a cosmopolitan atmosphere.”

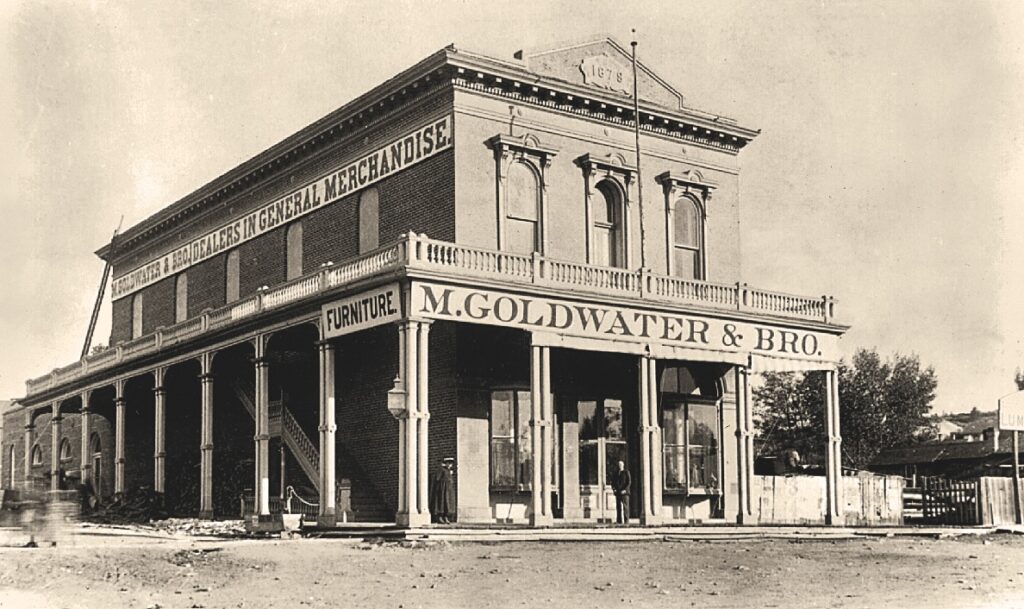

One of those strivers who kitted up a wagon and set out for Gila City was Michael “Big Mike” Goldwater, who had been born into a Jewish family in Russian-speaking Poland in 1821. He worked as a tailor in Paris and London before emigrating to San Francisco during the rush of 1849. Goldwater found a living supplying dry goods and beer to the miners in the Sierra. When he heard of the fabulous diggings at Gila City, he rode in from Los Angeles with a wagon full of groceries and clothes.

But a shipment of another kind spelled disaster for Gila City after the placer ore disappeared. The newer deposits in the bluffs were too far away from the river for easy hand-washing, and the muckers needed a steam pump to get the water over to the inland troughs. They pooled capital and bought this expensive piece of equipment, which had to be shipped up the Sea of Cortez. But before it could even be loaded onto a wagon at Yuma, the schooner carrying the pump sank on March 17, 1859. With it went the future of Gila City.

The settlers drifted away, looking for the next big thing. Big Mike opened a new store in Prescott, where he got rich and later became the grandfather of U.S. Senator Barry Goldwater. A Confederate veteran named Jack Swilling also had enough and tried to become a farmer in the Salt River Valley by digging out old canals.

A few diehards stayed behind to dry-wash the pulverized ore by tossing it up in the air over a blanket—a crude method of making at least some of the waste rock blow away while leaving the heavier gold-bearing minerals. But without water, it was dirty and inefficient. The Gila River, always temperamental, flooded the dying town in 1862. By the time Browne and Poston got there the following year, there was almost nothing left. An irrigation canal now flows through the site today, even though the Gila’s water has long since disappeared, a victim of upstream dams.

Luck and Lincoln

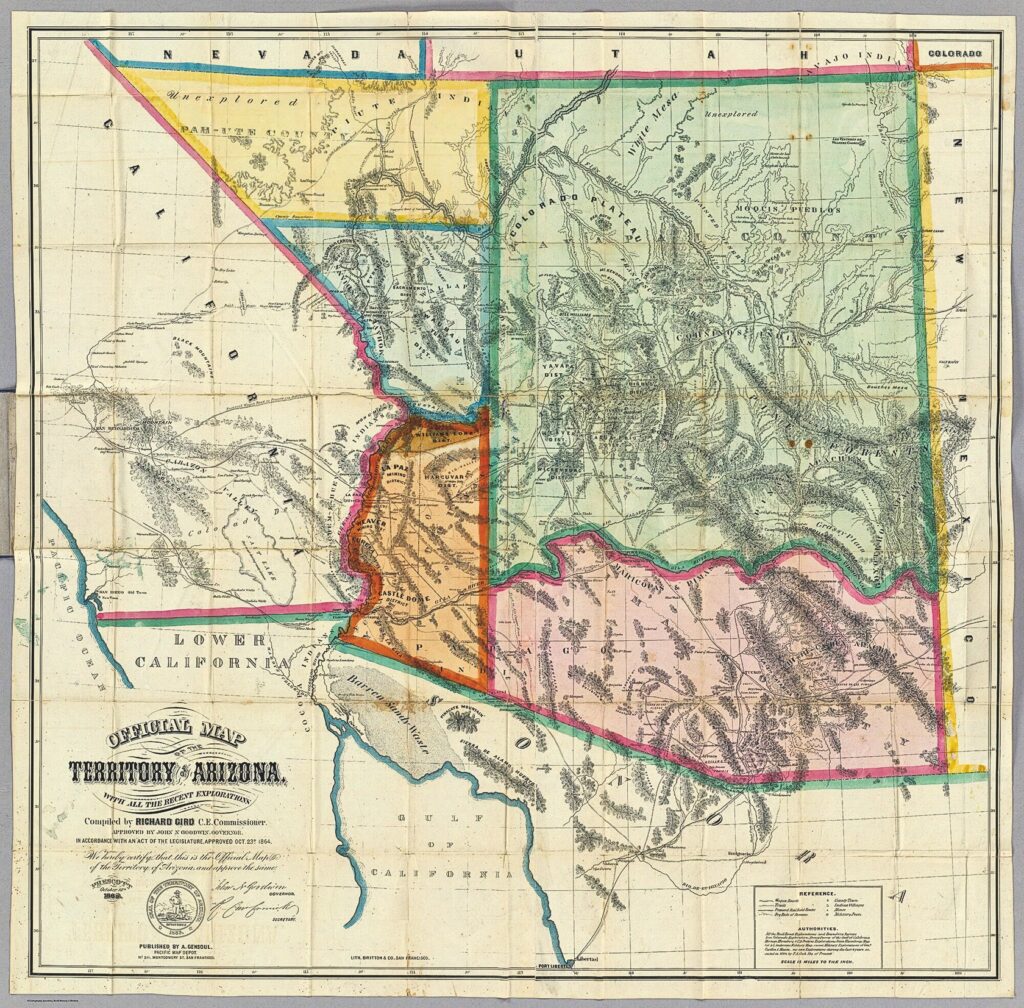

History sometimes serves up odd coincidences. Just a few days before Browne’s arrival in the remnants of Gila City, an appointee of Abraham Lincoln named John N. Goodwin had signed the paperwork that established the Territory of Arizona, not far from the site of present-day Holbrook.

He was traveling with an entourage from Santa Fe over the new Beale Wagon Road and nobody was quite sure when they had crossed the newly established border drawn by Congress that carved off the new territory from New Mexico. The party camped at a meadow called Navajo Spring on December 29, 1863, only when everyone felt sure they must have crossed the invisible line on the map. They raised a flag and sent scouts looking for wood for a fire. Goodwin took an oath as governor, signed a proclamation constituting the legislature, and everyone dined on antelope steaks before moving on the next morning.

That official act at Navajo Spring readied the way for a flood of immigrants to come into a rough new American territory already populated by a complex social mix of Native people and Mexican pioneers, along with a staggering bonanza of silver timber, copper, gold and grazing lands for those who were ruthless or lucky enough to stake a first claim or jump in on somebody else’s.

All those young men in a hurry to get to Arizona and cash in might have looked to Gila City for a lesson in temporality. Before Browne and Poston themselves moved on the next morning for a journey “across a series of gravely deserts” through a thicket of exotic-looking “suaro” cactus, Browne paused to offer a verdict on the fate of Arizona’s first boomtown. His words might have served as a warning to hundreds of other fast-buck Southwest metropolises soon on the way.

“There was ‘pay dirt’ in the hills, but it didn’t pay to carry it down to the river and wash it out by any ordinary process,” he wrote. “Gila City collapsed. In about the space of a week it existed only in the memory of disappointed speculators.”