“Tea must be universally renounced . . . and the sooner the better,” wrote John Adams, enroute to the first Continental Congress in 1774. Patriotic Americans agreed and embraced coffee as their favorite drink.

“Tea must be universally renounced . . . and the sooner the better,” wrote John Adams, enroute to the first Continental Congress in 1774. Patriotic Americans agreed and embraced coffee as their favorite drink.

To the American colonists, tea was a detested symbol of British oppression, due to King George’s high tax on it. In Boston Harbor and several other ports, the colonists protested this odious tax by boarding British ships and throwing cargoes of tea into the ocean. Colonial coffeehouses became a magnet for pro-revolution Americans and the site of many heated political discussions.

After the Revolutionary War, tea drinking enjoyed a revival until the War of 1812, when Americans again rejected the British beverage. After this war, Americans became staunch coffee drinkers and served tea only occasionally, usually at genteel teas for ladies. In contrast to wimpy tea, coffee was an invigorating, robust drink that provided a jolt of energy, which was why strong coffee became a necessity for many Americans headed for the Western frontier.

Many diaries and letters confirm the importance of coffee to Western pioneers. Josiah Gregg, a trader who made eight trips to the West in the 1830s, marveled at the pioneers’ love of coffee. “The insatiable appetite acquired by travellers upon the Prairies is almost incredible, and the quantity of coffee drank is still more so,” he wrote. “It is an unfailing and apparently indispensable beverage, served at every meal.” Cavalry Lt. William H.C. Whiting wrote that coffee and tobacco were indispensable to the frontiersman. “Give him coffee and tobacco, and he will endure any privation, suffer any hardship.” Julia Brier, one of the first people to cross Death Valley, said, “Our coffee was a wonderful help and had that given out, I know we should have died.”

Cowboys were undoubtedly the most devoted group of coffee drinkers in the West. As a rule, they liked it strong, scalding hot, and barefooted (black). They derided weak coffee as dehorned bellywash or brown gargle. In many ranch kitchens, the cook did not remove the grounds from the pot after the coffee was brewed but added new grounds to the old until the pot was too full to hold more. The cowboy’s love of strong coffee was the basis for this oft-repeated recipe:

A pot of coffee steaming over an open fire or on a bed of hot coals was a fixture on cattle drives. A three- to five-gallon pot, usually made of tinned iron and blackened by smoke, was standard for an outfit of 10-12 men. The smart chuck wagon cook did not skimp on coffee because it was the wrangler’s mainstay, day in and day out. One cook, Oliver Nelson, wrote that he used about 175 pounds of coffee beans each month. “The men half lived on coffee,” he wrote. Gen-erally, cow-punchers drank hot java with every meal —and between meals when they could get it. When they worked four-hour shifts all night, they needed coffee before they left the campfire and coffee when they returned. When the weather was bad and sleep was impossible, coffee kept them alert. Trail boss George Duffield wrote that during one storm, his men were in the saddle for 60 hours straight, but “hasty rations” of bread and coffee kept them going.

Before the Civil War, many settlers were forced to drink mock coffee made with rye, parched corn, bran, or okra seeds because good coffee was expensive and hard to find on the frontier. This changed in the 1860s, when new technology revolutionized the coffee industry. In 1862, inexpensive, lightweight but durable paper bags became available and were used for packaging peanuts. In 1864, Jabez Burns, a temperance advocate who preferred coffee over whiskey, invented an efficient commercial coffee roaster. Burns’ roaster used a clever double-screw arrangement that constantly turned the beans, allowing them to roast evenly. (During the roasting process, green coffee beans are heated and then cooled, causing chemical changes that enhance the flavor.)

John Arbuckle was a marketing whiz who revolutionized the coffee business, using Burns’ roaster, the paper bag and an invention of his own. In 1860, John Arbuckle, his brother Charles, and two other men formed a wholesale grocery business, McDonald & Arbuckle, in Pittsburgh. Although the firm sold many foods, John Arbuckle focused on coffee because he believed that it had great profit potential. When he heard about Burns’ invention, he bought one and began selling roasted coffee in one-pound paper bags. To preserve the fresh taste of the roasted coffee, Arbuckle experimented with glazing the roasted beans to seal in the flavor and aroma. In 1868, he was granted a patent for his glazing process, which prolonged the shelf-life of roasted coffee.

Other coffee manufacturers ridiculed Arbuckle’s innovations, but consumers loved his roasted coffee. Previously, the housewife had been forced to buy green coffee beans and roast them at home. She used either a shallow pan over a cookstove or a long-handled roaster, which looked like a bed warmer, over a fire on the hearth. In either case, she had to continually shake the beans to prevent burning. An early cookbook advised, “Stir often, giving constant attention . . . not one grain must be burned.” Despite the cook’s best intentions, home roasting often produced charred, foul-tasting beans.

The demand for Arbuckle’s roasted coffee was so great that he soon had to hire 50 women to pack the bags. Over several years, his company, renamed Arbuckle Brothers, secured the rights to patents for packaging equipment invented by Henry E. Smyser. The resulting automated system replaced many workers and accelerated the manufacturing process. By 1881, Arbuckle’s company was operating 85 coffee roasters. The packaging equipment took the roasted coffee directly from the hopper, filled the bags, weighed them, sealed them, and then applied the labels. Over the years, Arbuckle’s bags carried several brand names, but the most famous was Ariosa.

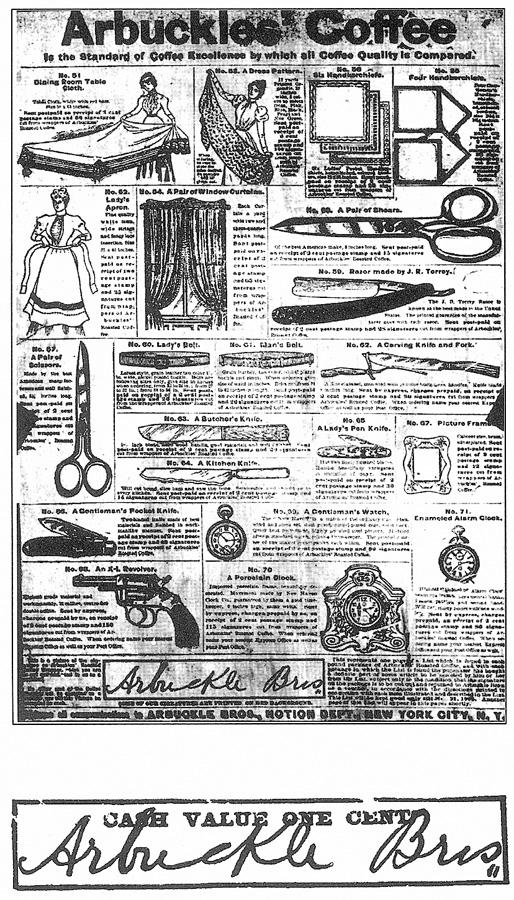

Even when sales were good, Arbuckle was always looking for new ways to promote Ariosa. Early in the 1890s, he decided to print a coupon on each bag of coffee. At first, the coupon was simply the words “Arbuckle Brothers” inside a rectangle. Later, the phrase “Cash Value One Cent” was added. These coupons were similar to trading stamps because the consumer could cut them out and redeem them for merchandise. Periodically, the company issued a catalog listing the merchandise and the number of coupons needed for each item. For example, 25 were needed for an apron, 28 for a razor, or 40 for a pocket knife. A dedicated coffee drinker could claim 12 yards of organdie for 100 coupons, or a double-action revolver for 150.

In a typical year, Arbuckle Brothers’ Notion Department, which was created to handle the exchanges, redeemed about 108 million coupons for about 4 million items. Rings were so popular that Arbuckle Brothers claimed to be the world’s largest distributor of them. In one year, the Notion Department mailed out 80,000 wedding rings, in addition to other styles. Because the coupons could be redeemed for so many different things, cowboys often called a green hand “Arbuckle,” suggesting that his services had been obtained in exchange for coupons. Since each coupon had a cash value of one cent, merchants and customers sometimes used them as legal tender, especially in drought years when cash was scarce.

Arbuckle’s coupons weren’t the only incentive for buying Ariosa. Even the empty containers were useful. Many ranch cooks bought Ariosa in 150-pound cloth sacks, which could be made into dish towels, aprons, bandages, and so forth. Even more versatile were Ariosa’s wooden shipping crates. The large crates, which held 100 one-pound bags, were made of sturdy Maine fir because they had to withstand shipment over many miles of rough road. After the crates had been carefully opened and emptied, the wood was used to build furniture, shelves, storage bins, chicken coops, and the like. Sometimes a crate was recycled as a crib for a baby or as a coffin when an in-fant died. The wood from several crates could be nailed to-gether for an adult’s coffin. Occasionally, a settler man-aged to col-lect enough crates to add a room onto his cabin. Arbuckle’s smaller shipping crates, which held 25 one-pound bags, were used for tool chests, wagon boxes, wood boxes, panniers, and such.

Although Arbuckle’s dominated the Western market, it had competition from several brands, especially Folger’s. James Folger was born into a distinguished Massachusetts family of whaling men so famous that they were mentioned in Moby Dick. In 1849, Folger and two older brothers joined many other hopeful New Englanders who sailed in a convoy of 14 ships in search of California gold. After a harrowing trip, the three Folgers reached San Francisco. While the two older brothers ventured into mining country, James Folger stayed in the city and worked at the Pioneer Steam Coffee and Spice Mills. Despite the name, this business was not steam-powered and did not acquire a steam engine for several years.

Later, in a small mining town, Folger opened his own store called Yankee Jim, but then returned to work for Pioneer Steam. By 1859, Folger was a full partner in this business which flourished at first and then foundered. After the firm went bankrupt in 1865, Folger bought out his partner, found a new partner with substantial capital, and eventually paid off the debts. Renamed J.A. Folger & Co., the business thrived during the 1870s. By 1880, Folger’s coffee was being sold all along the Pacific Coast and as far inland as Montana.

After Folger died in 1889, his son decided to expand the business and to challenge Arbuckle’s in the Lone Star State. Young Folger and his sales manager chose to sell their high-quality Golden Gate Coffee in Texas and to make a virtue of its high price. The sales slogan flatly stated “No prizes. No coupons. No crockery. Nothing but satisfaction goes with Folger’s Golden Gate Coffee.” This strategy worked. Within three years, the Texas sales force grew from one man to three.

Ariosa, billed as “the coffee that won the West,” outsold Folger’s for decades. Then the tables turned. Folger’s became one of the largest-selling national brands, but Arbuckle’s faltered after John Arbuckle died. Although his two sisters and a nephew tried to manage the business, Ariosa sales gradually declined. They introduced a new brand, Yuban, which had promise but suffered because they refused to spend money on national advertising. Then they quietly sold Yuban to another company, and in 1937, sold the rest of their companies to General Foods which also acquired Yuban a few years later. When John Arbuckle’s last sister died, his vast fortune had disappeared. There was not even enough money to pay her debts and personal bequests.

Arbuckle’s golden age may have ended, but the name would forever be associated with cowboys. Like six-shooters and barbed wire, strong coffee had played an important role in taming the West. At home and on the trail, it was the cowboy’s favorite pick-me-up.

ANNE COOPER FUNDERBURG is a history buff and freelance writer in Mandeville, Louisiana and the author of Chocolate, Strawberry, and Vanilla: A History of American Ice Cream. Her new book, Sundae Best: A History of Soda Fountains is forthcoming.

Photo Gallery

– True West Archives –

– Wyoming Division of Cultural Resources –

– True West Archives –

– Springfield Aromry National Historic Collection –