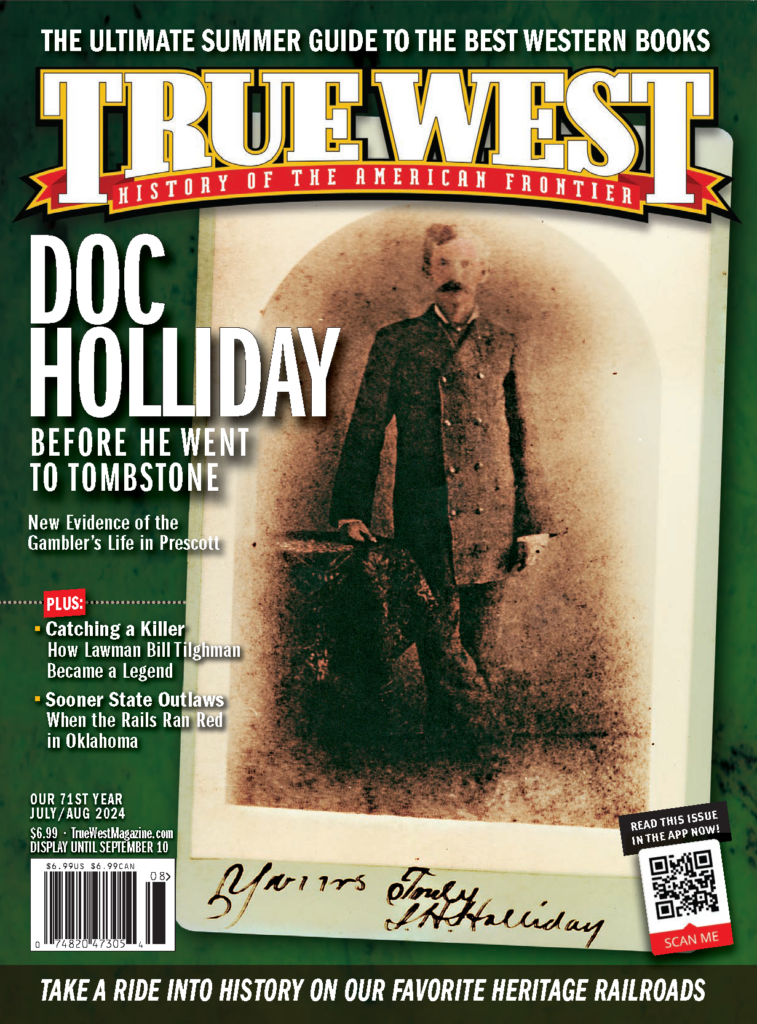

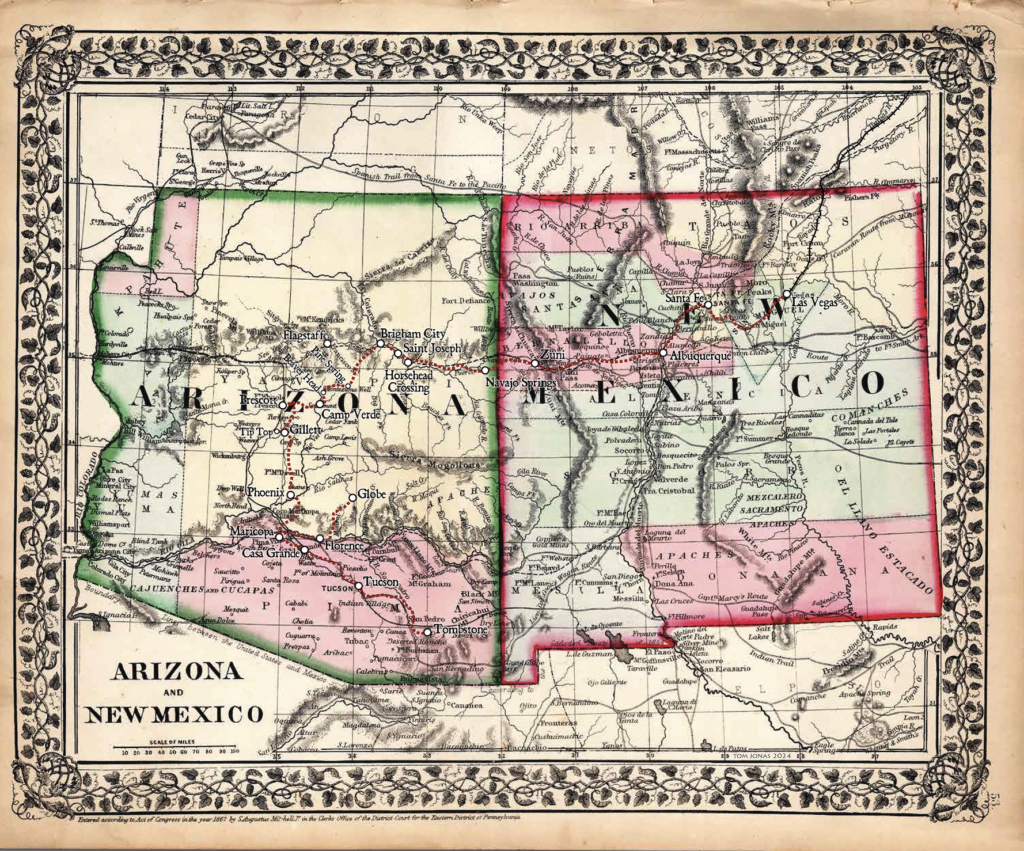

New evidence of his life in Prescott reveals the gambler was on the move back and forth to New Mexico before joining the Earps in Cochise County.

With additional research by Gary Roberts, Stuart Rosebrook, Tom Jonas and Mark Lee Gardner

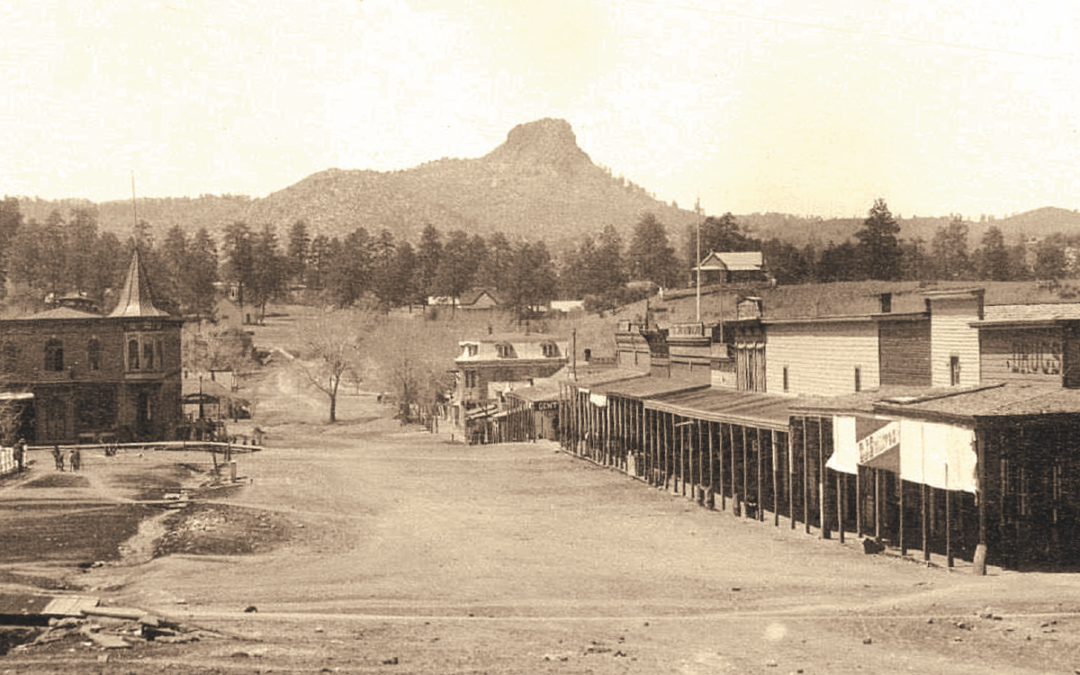

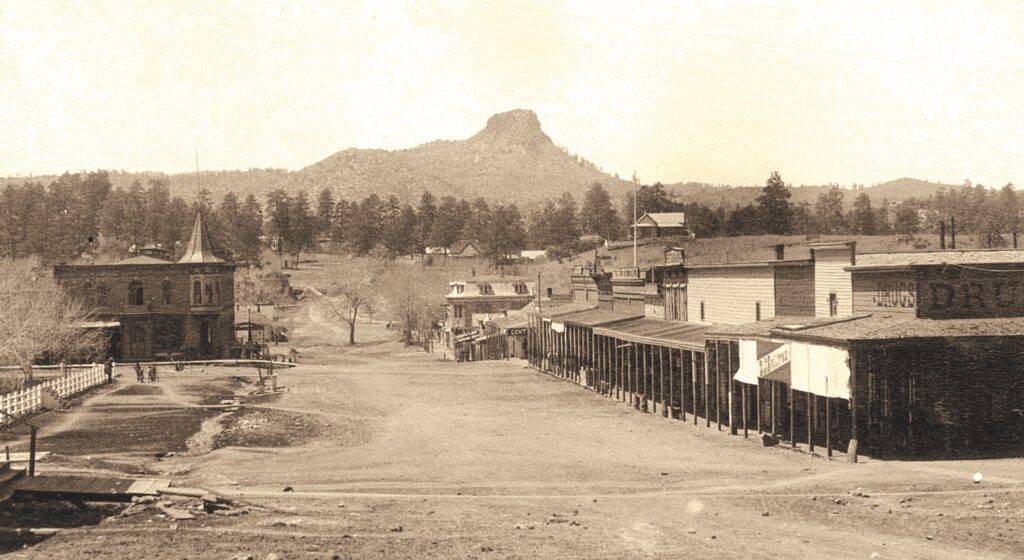

History buffs in Prescott, Arizona, know that the legendary John Henry “Doc” Holliday lived in Prescott before moving to Tombstone. Most, however, don’t realize that Doc actually spent two separate tenures in their mountain town, the first during the winter of 1879-80.

Doc went to Prescott by way of Las Vegas, New Mexico. His friend Wyatt Earp had gotten the hell out of Dodge City, Kansas, because he’d heard from older brother Virgil, constable of Prescott, about a new boomtown in southern Arizona with an odd name, Tombstone. No one knows precisely why Doc decided to join the Earp party almost a year after he heard about Wyatt’s Tombstone plans.

Doc Holliday avoided notoriety while living in Prescott in the winter of 1879-80 and the late spring and summer of 1880. All Artwork and Images Courtesy True West Archives Unless Otherwise Noted

Holliday, with his lover Kate Elder, arrived in Prescott in early November 1879. Doc and Kate found boarding in town, while Wyatt and his lady Mattie, brother James and his wife and stepdaughter, lodged with Virgil and Allie. Wyatt’s time in Prescott was short, indeed more like an “extended layover” than a sojourn. He and Virgil were anxious to get to Tombstone while the pickings were still good.

Doc, who was making the switch (maybe not intentionally) from dentist to full-time professional gambler, found Prescott to his liking and decided to lag behind for the time being. In the center of town was Whiskey Row, the gambling center of Arizona Territory. Another possibility is that it was Kate who liked what she saw, and convinced Doc to hunker down. Perhaps she was trying to keep Doc from Wyatt, whom she didn’t like. Or it might have been the climate of the Central Arizona Highlands, considered by many to be one of the best in the world. It’s common knowledge that Holliday suffered from tuberculosis. Prescott would become a major treatment destination for tuberculosis patients in the early 1900s, and surely Doc sensed that central Arizona was healthier for him than southern Arizona.

Tombstone vs. Prescott

Doc might have been doubtful about Tombstone all along. He has often been depicted as having been beholden to Wyatt, even in a puppy-dog manner. But Holliday was his own man who walked to the thump of his own cask, and he seemed in no rush to join Wyatt in the fledgling Pima County community.

It’s possible that Doc lingered in Prescott because its newspaper, the Weekly Arizona Miner, had started to print negative news about Tombstone. When the area first started booming, the reports were very positive, noting that the silver strikes there were good for Arizona Territory’s chances of becoming an American state. As early as February 1879, the Miner affirmed, “Tombstone District is no sham, but contains many wonderful veins, which are calculated to bring in thousands of people to that section.” Similar information continued through September, and Virgil Earp was surely reading it and sending the news to his brother Wyatt in Dodge City.

As time went on, however, the reports turned negative. By September 12, it was “The Tombstone section is keeping up its reputation in cut-ting and shooting.” Some of the articles (which were more like editorial commentaries) were published out of jealousy because a major migration of people from Prescott looking to make their mark in Tombstone had left the territorial capital. Although it was small and isolated from other towns, Prescott was still one of the busiest places in the West. It was a people magnet in Arizona Territory because it was the capital. And it wanted to remain the capital. There was a fear that since the population was larger and growing in southern Arizona, the capital would need to move as well.

Not only was Prescott’s population declining in 1879, capitalists were passing through but not staying. They too were heading to Tombstone. By the time Doc and Wyatt arrived in Prescott in November, the news was mostly derogatory toward the boomtown.

Virgil Earp was just one of many Prescottonians leaving for Tombstone, but on November 14, the Miner singled him out: “[V.] W. Earp is about to pull out for Tombstone, which is just now the great center of attraction. We don’t like tombstones and shall avoid them so long as possible.” No small number of those who left the Central Arizona Highlands for southern Arizona, like Virgil, played roles in the legendary Tombstone dramas of the early 1880s.

On November 21, near the time the Earp party was leaving town, the Miner issued a more direct and cautionary statement: [B]usiness is much overdone in that bonanza land. So we would advise those who think of going there to consider before they leap.” If Doc already had doubts about Tombstone, declarations like these certainly would have fed them. Similar warnings continued throughout 1880.

In early 1880, Doc and Kate went to Gillett together, but left separately. Kate went to Globe and Doc returned to Prescott. Photo taken by D.F. Mitchell

Kate vs. the Earps

Kate was never fond of the Tombstone idea and thought the Earps were bad news. If we are to believe Kate (who was known for offering questionable and contradictory stories), she and Doc argued incessantly about Tombstone—which he apparently had reservations about as well—and Wyatt Earp. Eventually, Kate declared, they agreed to temporarily separate. She’d go to Globe, and she did. Doc would head to Tombstone, which he didn’t. Instead, he went back to Las Vegas, New Mexico, to settle some personal business.

There’s a Prescott legend that started with author Stuart Lake, who claimed that Wyatt Earp told him that Doc had a winning streak playing faro on Whiskey Row which resulted in a staggering sum of $40,000. Today that figure would be worth over $1.2 million.

On March 6, 1932, Anton Mazzanovich, a famous history chronicler during the time that Lake’s popular Wyatt Earp: Frontier Marshal was published, wrote to the editor of the Prescott Evening Courier asking if any old-timers knew anything about it. In Mazzanovich’s mind it was all “apple sauce. As all the faro games put together in Prescott at that time could not show that amount of money.” He went on to claim that the most money Doc ever saw was the $8,000 his grandmother in Georgia had left him after her death. Actually, the inheritance money came from Doc’s mother, Alice, who had died in 1866, but it appears no one responded to Mazzanovich’s question.

While Doc lived in Prescott his name never surfaced in the local newspaper. However, he was remembered. In an 1884 Prescott Weekly Courier, when a report was published about Doc shooting a man in Leadville, Colorado, he was described as “formerly a well-known Prescott sporting man.” Unquestionably, Holliday had made an impression on Whiskey Row. Pinpointing any saloon he may have patronized is impossible to do with certainty, but the Cabinet Saloon—“the chief faro and gambling place in the village” according to Gover-nor Fremont’s daughter, Lily—is a likely location. Today, the Cabinet is the famous Palace Restaurant and Saloon.

Inexplicably, a Prescott legend has whittled Doc’s winnings of $40,000 to $10,000, still a wildly high sum (over $300,000 today). It’s reasonable, however, to conclude he might have won a fair amount on the Row, as Doc was able to return to New Mexico to pay off a debt related to a saloon he’d co-owned. He also appeared in a Las Vegas courtroom on March 12, answering to a pair of illegal gambling charges (which were dismissed).

Doc Returns to Prescott

Holliday was back in Prescott that spring, probably by May. His name, written as “J. H. Holladay,” appeared in the 1880 Federal Census for Yavapai County. It’s difficult to remember sometimes that Doc was a young man at this time, being only 29 years old. His occupation was listed as dentist. The owner of the boardinghouse where Doc rented a room was Richard Elliott, a man who wore many hats.

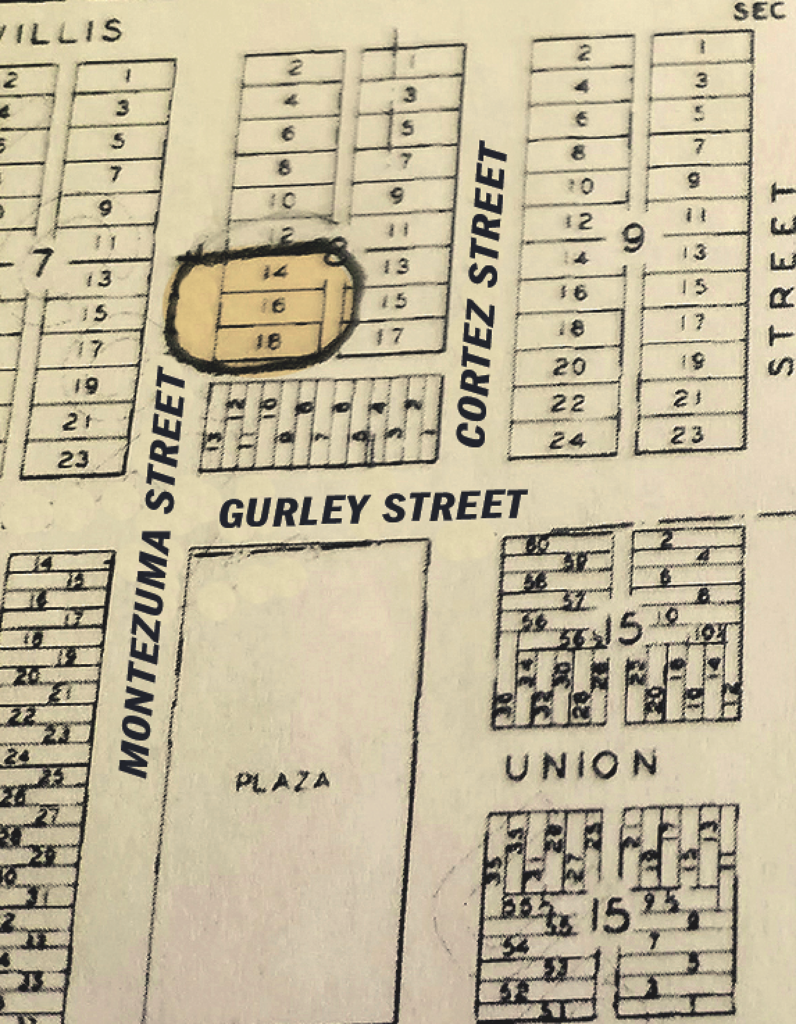

The first mention of Elliott in Prescott came in the Miner on March 23, 1867, when he, along with several significant Prescott pioneers, signed a petition to remove squatters who were settling on Prescott’s Plaza and attempting to set up businesses. Arriving in Yavapai County as a former school teacher, Elliott, over time, became a successful miner, furniture maker, treasurer for

the Masons, corn-sheller (using steam), picture-frame manufacturer, temperance leader, popular singer and singing teacher, windmill operator, match manufacturer and boardinghouse owner.

After a bit of gold mining success on Lynx Creek, Elliott bought Lot 16 of Block 8 of downtown Prescott on June 25, 1867, which was on Montezuma Street just above Gurley Street. He added Lot 18 on October 4. By 1872, Elliott had added Lot 14 to his collection. That year he built a good-sized house, house 52, according to the Yavapai County census, on these lots. On November 19, 1875, Elliott experienced the tyranny of fire like so many other frontier people when his “fine frame building” burned down. At first, he thought he wouldn’t be able to rebuild, but rebuild he did—bigger and better. Elliott’s new, large house sat within easy walking distance of Whiskey Row. A busy parking lot is there today.

Also living in Elliott’s house in 1880 was the secretary of Arizona Territory, John Gosper. In 1880, Arizona had its most illustrious but also most ineffective territorial governor, John C. Fremont, known to the world as the “Great Pathfinder.” Fremont’s ineptitude was primarily due to him being voluntarily absent much of the time, almost to the point of abandonment of his post. Consequently, Gosper became the most active acting governor in Arizona’s history. In fact, Fremont was absent from Prescott the entire time during Doc’s second tenure in the mountain town.

Did Gosper and Doc get along? Did they become friends? Conjecture and assumptions have been made, but virtually nothing is known about the nature of their relationship. When trouble came to Cochise County and Tombstone in 1881, however, it was primarily Gosper who tackled the problem, not Fremont.

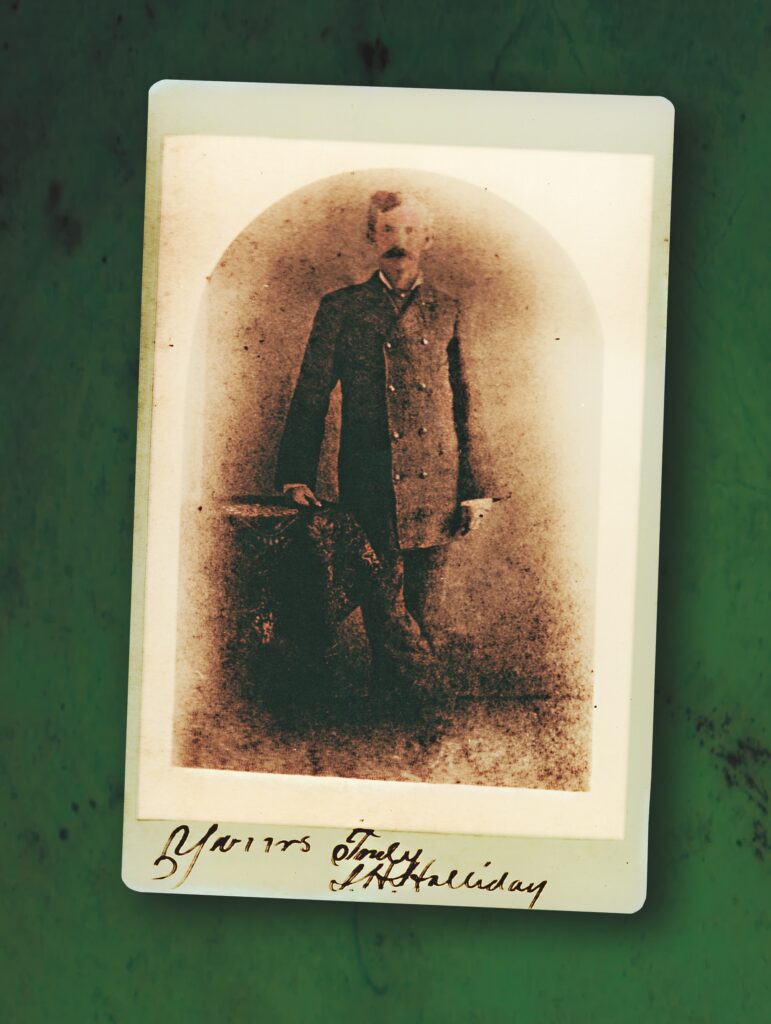

The Famous Photo

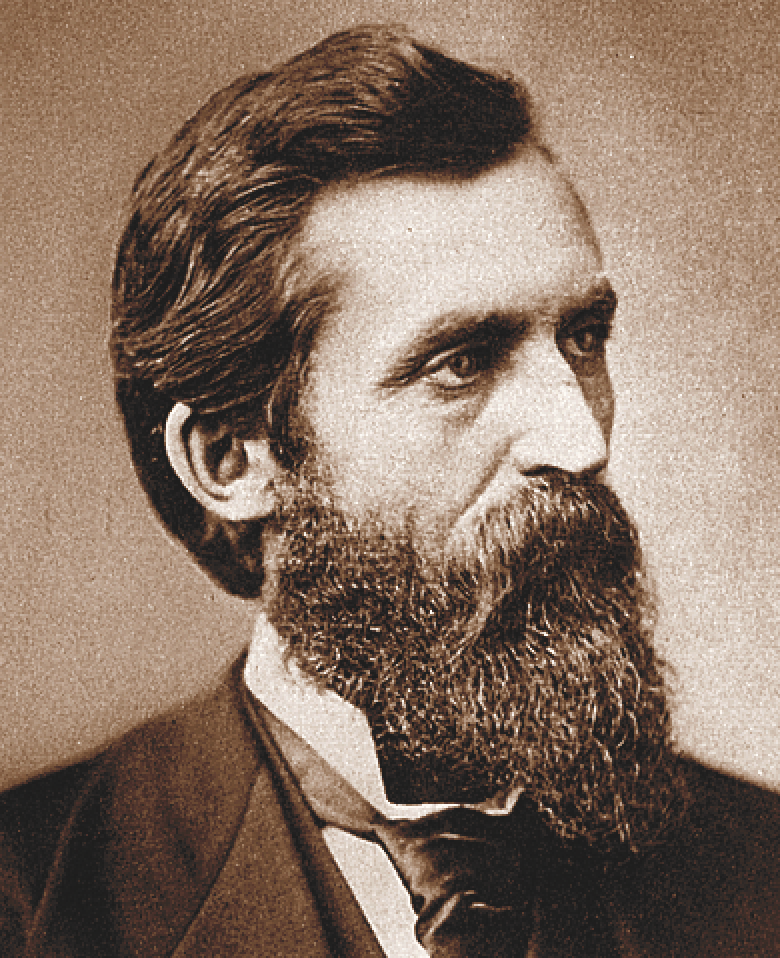

The most notable thing Doc did in Prescott didn’t become known until the 1970s. One of the only two verified photographs of him was taken by pioneer photographer Daniel Francis “D.F.” Mitchell at his Capital Art Gallery on North Cortez Street.

D.F. Mitchell of Massachusetts arrived in Prescott in June 1876 by stagecoach. By September, the Miner reported that Mitchell was producing photographs of Arizona scenes, as well as “[h]uman likenesses, true to nature.” The July 25, 1879, Miner gratuitously reported that “D.F. Mitchell, the photo-grapher, is kept quite busy making the handsome faces that are so great in this sec-tion of the world. Get your picture taken, and give it to your sweetheart.” During which of Doc’s two tenures in Prescott he stepped into Mitchell’s studio is anyone’s guess.

Did Mitchell know who J. H. Holliday was? Probably not. In the archives of Sharlot Hall Museum are many duplicates that Mitchell made of his photographs. Doc’s isn’t one of them. The raw truth, Holliday wasn’t yet the legend that a gun battle in Tombstone later made him. Of course, there was no way Mitchell could have predicted that his photograph of a dentist from Georgia would become his most famous.

In 1973—over 90 years after the likeness was taken—in a small book that didn’t sell well titled In Search of the Hollidays by Albert Pendleton Jr., and Susan McKey Thomas (who was related to Doc from his mother’s side, the McKeys), it was revealed that there existed a full-length photograph of Doc that he’d sent to his mother’s sister, his Aunt Ella. And it was signed, “Yours truly, J. H. Holliday.” He may have had copies made and sent out, but there was only one in the family’s keepsakes. Furthermore, on the back was the name of the photographer, D.F. Mitchell of Prescott, Arizona.

A couple of observations can be made from the image. One, although Doc was only 29 years old at the time, he seems older. Tuberculosis had clearly taken a toll on him. This may explain why Holliday has sometimes been portrayed by older actors in movies and television shows. Two, Doc’s apparel says something about him. He is wearing a double-breasted frock coat that a banker or lawyer may have worn in the 1880s rather than a flashy gam-bler. According to Holliday biographer, Victoria Wil-cox, those who knew him mentioned that this was typical of the man, and the dentist.

Martha Wiseman McKey had possession of the photograph at the time In Search of the Hollidays was published. The family later sold it to Craig Fouts, a notable and reliable collector of Western photographs who was, according to Holliday biographer Dr. Gary Roberts, “a stickler for provenance.” He sold his collection to billionaire Bill Koch.

Although the Prescott image of Doc became verified on the spot in 1973, it wasn’t widely seen by the public for two decades after Fouts bought it. It was published in Ben Traywick’s 1996 biography of Doc, Casey Tefertiller’s trailblazing Wyatt Earp: Life Beyond the Legend in 1997, and in Karen Tanner’s biography of Doc in 1998. But it wasn’t until 2006 when Gary Roberts—who obtained a copy from Fouts—used the Prescott image on the cover of his definitive biography of the sometimes gunslinging, often gambling Georgia dentist, Doc Holliday: The Life and Legend, that it became widely seen. Today, it’s possibly the most used image of Doc, the one that shows him as he would have appeared in Tombstone, and has the bonus of bearing his signature.

The Siren Call of Silver

Deductions by historians have been made as to why Doc finally left Prescott. Some have conjectured that Prescott was too tame for him, or that his luck ran out on Whiskey Row. That’s highly doubtful. First, that would imply that Holliday was looking for trouble, which he needed no help doing. Second, Whiskey Row was still the gambler’s mecca of Arizona in 1880.

In fact, Prescott snickered at a report that came from Tombstone in June 1881 bragging about a poker game (in which Doc’s enemy Johnny Tyler was a player) that had lasted “twenty-four hours with an ante of $2.50 each, taking $10 to play.” According to the Miner this was child’s play. “Four gentlemen of Prescott have had a game running during the last forty-eight hours with an ante of $4, taking $16 to come in and see.” The report ended with an admonition: “Tombstonites must look well to their laurels.”

More than one historian has surmised that Doc left because the gambling laws in Prescott changed to the detriment of faro dealers. This claim is easily debunked. True, there was a $500 quarterly gaming table license fee initiated in Arizona in April 1880. However, it was only true for the counties of Maricopa, Yuma and, yes, Pima, which Tombstone was still a part of, and where Doc would be in six months’ time. As a faro dealer and gambler, Doc would have been better off staying in Prescott where a license to run a table was only $15 a month.

The most likely explanation is that he left Prescott for Tombstone because of Wyatt’s urging and the lure of the boomtown. After his final stint in Prescott from May to August 1880, the Georgia gambler caught the stage south to Tucson, and then Tombstone—and destiny with the Earps and eternal fame. Or infamy. Take your pick. Regardless of one’s analysis, he became a key figure in what is possibly the most legendary and debated true drama in Wild West history.

Bradley G. Courtney’s latest book project is The Prescott/Tombstone Connection. “Doc Holliday Before He Went to Tombstone” is adapted from an earlier version published in the February 2024 edition of The Tombstone Epitaph.

Doc in Stages

As soon as the transcontinental rail line was completed in 1869, travel in the West began to change rapidly.

By October 1879, when Wyatt Earp picked up Doc Holliday and Kate Elder in Las Vegas, New Mexico, the West was entering the era of the Iron Horse. The Earp party was traveling by buckboard, a popular mode of transportation across the West. In fact, Wyatt had hoped to use his buckboard for a stage line between Tombstone and Tucson but discovered upon his arrival that a successful stage line with a covered coach was already in service.

But what about Doc and Kate? After they decided to stay in Prescott, Arizona, rather than continue to Tombstone with the Earp party, which now included Virgil and Allie, it is known that Kate and Doc left sometime in the early months of 1880 for Gillett. Kate later left for Globe, Arizona, while Doc returned to Prescott. In March of 1880, Doc left the Arizona territorial capital for Las Vegas, New Mexico, and returned to Prescott in May 1880.

But what did they travel in? Open buckboard, covered buckboard with multiple seats, a mud-wagon style stage or the top-of-the-line Concord coach?

The answer is that it could have been any of those possibilities and all of them carried some kind of freight and mail, which was the base of profit for the stage lines.

But consider these facts: travelers in 1879 recounted to multiple newspapers how rough it was to travel in the Southwest by buckboard stage. One rode in a two-seat mail hack that had room for just two passengers, one seated with the driver, and one in the back. But as the railroads pushed into southern Arizona and across northern New Mexico, Concord coaches began to replace buckboard-style coaches as reported in The Santa Fe New Mexican in February 1880.

Will we ever definitively know exactly what kind of stagecoach Kate Elder or Doc Holliday traveled in? No, probably not, but whatever it was—covered buckboard, Celerity style mud wagon or brand-new Concord coach—it had to have had enough protection from the elements in the winter and spring of 1880 to not kill the consumptive dentist-turned-gambler.

—Stuart Rosebrook

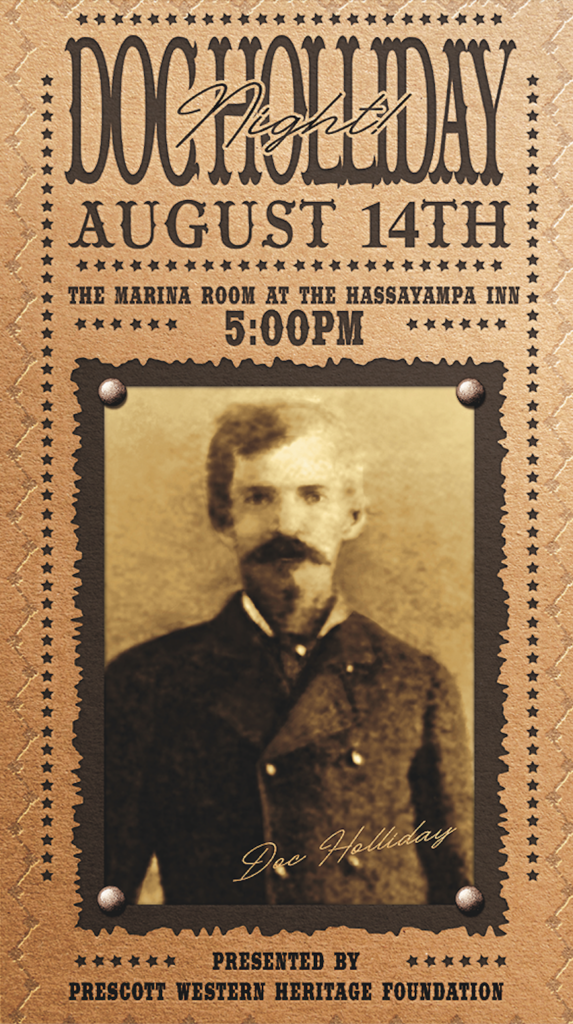

Doc Holliday Gets His Due

At 4 p.m. on August 14, 2024, a special plaque will be unveiled next to 123 N. Montezuma Street, behind Bashford Courts, in Prescott, Arizona, commemorating where Doc Holliday lived in the territorial capital in May to August 1880. The plaque ceremony will be followed by a reception with a no-host bar at 5 p.m. in the Marina Room at the historic Hassayampa Inn at 122 Gurley St. The reception, including live music by Tyler Gummersall and an 1880s fashion contest, is presented by the Western Heritage Foundation of Prescott. Tickets are $25. For more information and details on the evening, which will include a raffle, please go to visitwhc.org to purchase a ticket.