Thirty seconds of withering gunfire raised John Henry “Doc” Holliday from frontier gambler to gunfighter immortal. Yet it was in a quiet little Colorado mountain community that the debilitated dentist demonstrated true grit. Forced to live a life half-dead, he confronted the curse of consumption—a confrontation that reached its climax on November 8, 1887, when Doc Holliday died in Glenwood Springs.

Thirty seconds of withering gunfire raised John Henry “Doc” Holliday from frontier gambler to gunfighter immortal. Yet it was in a quiet little Colorado mountain community that the debilitated dentist demonstrated true grit. Forced to live a life half-dead, he confronted the curse of consumption—a confrontation that reached its climax on November 8, 1887, when Doc Holliday died in Glenwood Springs.

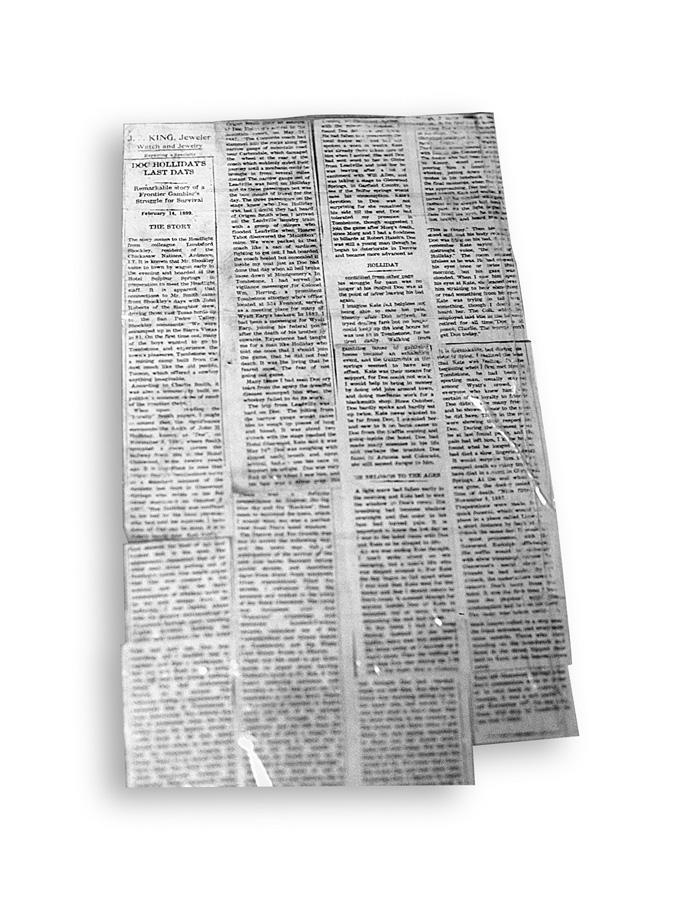

The circumstances surrounding Holliday’s final struggle with the deadly disease have been gleaned from obituaries and scattered reminiscences, some verifiable, some anecdotal, and some apocryphal. Until now, no detailed first-hand account of those final days and hours was known to exist. Fittingly, the recently discovered details had been preserved by a Tombstone personality and ally of the Earp/Holliday faction during that deadly 1881-82 era, Origen C. “Harelip Charlie” Smith.

Mining speculator, mechanic, rancher, and inveterate lawman, Connecticut-born Charlie Smith (born 1849) arrived in Tombstone in 1880 with only 20 silver pieces and a duffel. A roommate and partner of Earp business associate Bob Winders, Smith soon became identified with the town’s Earp faction, probably through his friendship with Morgan Earp. He was a “runner” for them in early 1882, joining the Earp posse at Hooker’s ranch. Although the newspapers did not mention him in 1885, he later claimed that he had left Arizona with the Earps. In subsequent years, Smith periodically assisted Fred Dodge in chasing various southwest Arizona outlaws. Eventually, he moved to Tempe where he served as justice of the peace for a number of years. “Steadfast in his friendships and zealous in his duties” (Arizona Republic, November 29, 1907), at the time of his death (November 28, 1907) in Tucson he was serving as a Maricopa County deputy sheriff.

In 1881, Charlie Smith met Lundsford Bryant Shockley, an Indian Territory native, who was helping to drive a herd from Abilene to Fort Huachuca. The ranch hands camped in the Hereford area, and it was there that Shockley and Smith established their friendship. Six years later, after being with Doc in Glenwood Springs, Colorado, Smith returned to Tombstone and began to write down notes for his memoirs. The following year he shipped these notes to Shockley, then living in Ardmore, Indian Territory, adding, “I am glad you are taking this up . . .” Apparently, Smith had sought Shockley’s collaboration in preparing his memoirs which included his days in Glenwood Springs. In 1899, Shockley shared the Glenwood pages of Smith’s memoir with W.D. Covington, publisher and editor of the Sulphur, Oklahoma Headlight. On February 14, the Headlight published Smith’s account.

No complete issues of the Headlight are known to exist. Shockley, fortunately, preserved the original published article among his effects, in a trunk stored in a Drake, Oklahoma, country schoolhouse. In 1917, a cyclone destroyed the school house, but Shockley’s trunk remained intact, passing through the hands of his descendants until it and its contents came into the possession of Shockley’s great-great-grandson, co-author Clifton Brewer. Brewer, in turn, brought the contents and, most significantly, the Headlight article to the attention of Holliday relative and co-author Karen Holliday Tanner. Over a century later, we present the article here in its entirety, and in its original form.

Sulphur Headlight

14 February, 1899

DOC HOLLIDAY’S LAST DAYS

Remarkable Story of a

Frontier Gambler’s

Struggle for Survival

The story comes to the Headlight from colleague Lundsford Shockley, resident of the Chickasaw Nations, Ardmore, Indian Territory. It is known that Mr. Shockley came to town by wagon early in the evening and boarded at the Hotel Sulphur Springs in preparation to meet the Headlight staff. It is apparent that connections to Mr. [Origen Charles] Smith came from Shockley’s days with John Roberts of the [John] Slaughter crew, driving those vast Texas herds up to the San Pedro Valley. Shockley comments: We were encamped up in the Sierra Vistas in ‘81. On the first time out, many of the boys wanted to go to Tombstone and experience the town’s pleasures. Tombstone was a mining camp built from the dust much like the old pueblo, Tucson, which offered a cowboy anything imaginable.

According to Charlie Smith, it was also a community built on politics; “a common cause of much of the troubles there.”

When upon reading the Harelip Smith papers, I might comment that the significance surrounds the death of John H. Holliday, known as Doc, on November 8, 1887, where Smith occupied a room across the hallway from him in the Hotel Glenwood, some twelve years ago. It is important to note that Origen Smith’s recollections serve as a standard account of the dentist’s last days in Glenwood Springs who wrote on his Sol Israel stationary on October 8, 1887, “that Holliday was confined to his bed by the local physician who had told his mistress: I have done all that can be done. It is in John’s hands now. And God’s.”

Origen Smith gives an account of Doc Holliday’s arrival to the mountain resort on May 24, 1887.

“The Concorde coach had slammed into the rocks along the narrow gauge of mountain road near Carbondale, which damaged the wheel at the rear of the coach which suddenly ended their journey until a mechanic could be brought in from several miles distant. The narrow gauge out of Leadville was hard on Holliday and its three passengers but was the best means of travel for the day. The three passengers on the stage knew who Doc Holliday was, but I doubt they had heard of Origen Smith when I arrived on the Leadville laundry train with a group of miners who flooded Leadville when Hoarse Tabot [Horace “Haw” Tabor] discovered the “Matchbox” [Matchless] mine. We were packed in that coach like a can of sardines, fighting to get out. I had boarded the coach heeled but concealed it inside my coat just as Doc had done that day when all hell broke loose down at Montgomery’s. In Tombstone, I had served as vigilance messenger for Colonel Wm. Herring, a prominent Tombstone attorney who’s (sic) office located at 534 Freemont, served as a meeting place for many of Wyatt Earp’s backers. In 1882, I had been a messenger for Wyatt Earp, joining his federal posse after the death of his brother by cowards. Experience had taught me for a man like Holliday who told me once that I should join the game, that he did not fear death. It was the living that he feared most. The fear of not going out game.

“Many times I had seen Doc cry tears from the agony the dreadful disease scourged him when the whiskey failed to do its work.

“The trip from Leadville was hard on Doc. The jolting from the narrow gauge would cause him to cough up pieces of lung and blood. It was about two o’clock when the stage reached the Hotel Glenwood. Kate said it was May 24th. Doc was coughing from almost each breath and upon arrival, had to use his cane to support his weight. Doc was very frail in body when I saw him, and his hair was a silver gray. His face showed the lines of age and looked sick in the eyes. His appearance resembled that of an older man, since pulling out of Hooker’s Ranch. One might argue that Doc was content in his actions and that his daily consumption of whiskey came to be his only escape from his suffering. I was rightly taken with the general surroundings of Glenwood Springs, upon reaching Eighth Avenue, holding my duffle and looking for the hotel.

“Kate had told me Doc was boarding. All I wanted was to register and find a bathhouse. I had run into Kate in the lobby who had sent this young bellhop, whom Doc had nicknamed Kenny [Art Kendrick], on an errand. The welcome feeling I experienced far exceeded that of Tombstone I soon discovered. The district was full of excitement when the train pulled into the station house. I recall most of all how many people were about on the streets.

“There was a definite resemblance to Denver; the big blue sky and the “Rockies,” that seem to surround the town, which I would soon see was a perfect view from Doc’s hotel window.

“The Denver and Rio Grande was due to arrive the following day [October 5], and the town was full of anticipation of the arrival of the new iron horse. Banners swung across streets, and merchant signs from store front windows. Great expectations filled the streets. I refrained from the moment and walked in the lobby of the Hotel Glenwood. The lobby was furnished with fine “Victorian” trimmings and elaborate knotted-Persian carpets, reminded me of the Cosmopolitan and Grand hotels in Tombstone, and the White Club House Room in Denver.

“There was this need to put down words on paper since leaving Hooker’s Ranch in 82. But, it was Kate’s enduring patience and devotion to Doc that gave me my inspiration to tell the story. There was a sense of fatalism in Kate’s voice, yet talk of the springs which had brought Doc to Glenwood, was the last hope the West had to offer a lunger like Doc. I suppose if there was a chance for Doc’s health to improve, he would take up its resources of Glenwood Springs.

“Writing this down is not to judge him for past actions, but to understand him. Doc’s memory seemed to be unaffected at times, although he lost much of his lungs over the years out West since leaving his beloved Georgia. I know the whiskey came to be his only escape from the pain that came with the consumption, and his desperate longing for home. There is no doubt that the short time Doc lived inside the Hotel Glenwood, [it] became his sanctuary. What transpired within the walls will leave a lasting impression. One that is etched in my memory.

“Coming to Glenwood Springs with the miners in October, I found Doc delirious and dying. He had fallen to a pneumonia the local doctor said, and had not spoken a word in weeks. Kate was already there taken care of him when I arrived. She said Doc had sent word to her in Globe from Leadville and told her he was leaving after a bit of excitement with Will Allen, and was taking a stage to Glenwood Springs, in Garfield County, to see if the sulphur springs would ease his consumption. Kate’s devotion to Doc was not surprising for she remained by his side till the end. Doc had tolerated my presence in Tombstone, though suggested I join the game after Morg’s death, since Morg and I had a fondness to billiards at Robert Hatch’s. Doc was still a young man though he began to deteriorate in Denver and became more advanced as his struggle for pain was no longer at his control. Doc was at the point of never leaving his bed again.

“I imagine Kate felt helpless not being able to ease his pain. Shortly after Doc arrived, he tryed (sic) dealing faro but no longer could keep up the long hours he was use to in Tombstone, for he tired easily. Walking from gambling house to gambling house became an exhausting event, and the treatments at the springs [never] seemed to have any effect. Kate was their means for support, for Doc could not work. I would help to bring in money by doing odd jobs around town, and doing mechanic work for a blacksmith shop. Since October, Doc hardly spoke and hardly sat up twice. Kate never wanted to be far from Doc. I consoled her and saw to it no harm came to Doc from the traffic coming and going inside the hotel. Doc had made many enemies in his life and perhaps the troubles Doc faced in Arizona and Colorado, she still sensed danger to him.

HE BELONGS TO THE AGES

“A light snow had fallen early in the morning and Kate had to shut the window in Doc’s room. His breathing had become shallow overnight and the color in his face had turned pale. It is important to know the last day as I was in the hotel room with Doc and Kate as he clinged to life.

“An era was ending Kate thought. I don’t write about an era changing, but a man’s life who was shaped around it. For Kate the day began to fall apart when I was told that Kate sent for the doctor and that I should return to Doc’s room. It seemed strange for anyone beside Doc or Kate to summon me at once. I went, expecting the end had come.

“In the lobby I had a strange feeling. Instead of the heavy traffic, there was this stillness in the hotel lobby as I hurried up to Doc’s room. Then the bellhop told me that Doc was sitting up. I felt relief for Kate. For a moment I had thought Doc had cheated death one last time. Doc had been found that morning sitting up by the maid who had awoke Kate who had slept in Doc’s chair that he liked sitting by the window in. The doctor was there when I got there. He was saying something to Kate, but his words didn’t make her feel better. For the first time in weeks, the details and the sound of Dr. B.’s [possibly Dr. Baldwin] voice was (sic) clear. She knew the end was upon him. Knowing Doc, I figured he might pull out another winning hand. It was not meant to be. This would be his last game.

“I did not know the complete story from the doctor who had been making house calls to Doc’s room the past few weeks. Though, I never doubted his opinion. In the final hour I knew one thing. Doc was about to cash in his chips. There were several Glenwood residents in the room, Sarah Copper [Sarah Field Cooper] and Walter Devereaux, whom (sic) shared a seat with Doc on the Concorde stage. The doctor who had been sent for by Kenny, stood over Doc pouring him a tumbler of whiskey, jotting down medical quotes in his notebook. During the final moments, when the end was approaching, Doc turned his head toward Kate and smiled. He turned up the tumbler with great fashion as he always had done in the past. As the light began to fade from his eyes, he took his last breath, and heard him say, ‘This is funny.’ Then his eyes stood still, and his body relaxed. Doc was lying on his bed, dead. I remember Kate saying in a distraught voice, “the end of Holliday” The room seemed lifeless as he was. He had opened his eyes once or twice that morning, but his gaze was clouded. When I saw him open his eyes at Kate, she leaned over him straining to hear something or read something from his eyes. Kate was trying to tell him something, though I doubt he heard her. The Colt, which he employed laid idle in the bureau, retired for all times. ‘Doc is at peace, Charlie. The worms won’t get Doc today.’

“It is unthinkable, but during his time of dying, I realized the loss that Kate was feeling. In the beginning when I first met him in Tombstone, he had been a sporting man, usually staying among Wyatt’s crowd, yet everyone who knew him, was certain of his loyalty to friends.”

Doc didn’t have many friends, and he showed honor to the ones he did have. Those in the room were showing their respect for Doc. During the moment when he at last found peace, and the pain had left him, I knew he had found what he longed for. Doc had died a slow, lingering death.

“It would surprise him to have escaped death so many times, to have died in a room in Glenwood Springs. At the end when Doc was gone, the doctor noted the time of death. “Nine fifty-five, November 8, 1887.”

“Preparations were made for a quick funeral, which would take place in a place called Linwood, a short distance by hack at two o’clock the same day. It would be a quiet procession, with the Reverend Rudolph officiating. His coffin would be elaborate with silver trimmings, donated by Glenwood’s social class and friends he had made. By 11 o’clock, the undertakers came to remove Doc’s body from the hotel. It was the first time I had seen the physical scars the consumption had left on his body. The body was taken away. A black hearse rolled to a stop near the front entrance, and everybody came outside. Those who were standing on the boardwalk and those in the street, tipped their hats to Kate as the hearse drove away.

“Kate left Glenwood Springs after Doc’s possessions were in order to be sent back to relatives in Georgia. It was a sad parting. I left November 10th, the day after Kate. Will stop by Leadville to see Bob I think.”

In Smith’s recollections, we experience a first-hand account of Holliday’s last days by one who knew him during the 1881-82 difficulties in Tombstone, when all hell broke loose down at Montgomery’s. Various oblique references establish Smith’s connection to the Earp faction, and in turn, his relationship with Holliday. The end result is a singularly significant account of Holliday’s tenure in Glenwood Springs; a primary account answering myriad questions that have lingered in the wake of the dentist-gambler’s death.

“Heretofore, an educated guess fixed the time of Doc’s arrival at Glenwood Springs in the spring of 1887, and a wire from Leadville had forewarned one of Glenwood Springs’ founders, Perry Malaby, of Holliday’s imminent presence (Denver Republican, November 10, 1887). Now, we know that he arrived on Tuesday, May 24, via a Concorde coach carrying, in addition to the notorious killer, two representatives of Glenwood Springs’ fledgling society: Sarah Field Cooper, whose husband, Isaac, was one of the builders of the Hotel Glenwood, and Walter Bourchier Devereaux, who owed his fortune to the Aspen mining camps.

The issue of Holliday’s deteriorating health is of particular interest. It is now certain that soon after he arrived, he tried dealing faro in several of the gambling houses, but the hours took their toll. Eugene Parsons recalled, “He walked down the street with a feeble tread and a downcast look. If he heard a shot, he raised his head with eager attention and glanced this way and that.” Eleanora Malaby related an incident that confirmed Doc had also hoped to support himself by doing some dental work. However, during her visit, he began to cough and excused himself. He went outside and she heard him coughing as though he would tear out his lungs. When he returned, he asked if she could come back another time. From Smith we learn that from his arrival, Doc had relied upon a cane to support his weight; we know that every breath brought forth a cough; we can visualize the tears of agony when the whiskey failed to kill the pain. Next, we discover that by October 4, Holliday had fallen to pneumonia and, having not spoken for weeks, lay delirious and dying with Kate devotedly at his side. Moreover, what of Kate’s role?

Kate (Mary Katherine Horony) related to Anton Mazzanovich that, from Glenwood Springs, Holliday had wired her “to join him,” which she did. They made up and she was with him to the time of his death (Bisbee Brewery Gulch, June 3, 1932). In 1935, she reiterated the story to Prescott confidante Albert Bork. Nevertheless, many skeptics question her truthfulness. In these recollections, Charlie Smith confirmed, once and for all, Kate’s presence with Holliday in Glenwood Springs. He revealed her “enduring patience and devotion” to the bed-ridden gambler as his life ebbed away. Moreover, in affirming Kate’s dedication, Smith also divulged his own. He sought work as a mechanic and otherwise resorted to odd jobs about town to support the three of them. Additionally, knowing that Holliday was not without enemies, Smith assumed the role of the sentinel, protecting the gambler and his mistress from whatever dangers might still be lurking.

Smith’s recollections also corroborate the claim of Art Kendrick, the surviving bellhop “Kenny,” that he attended Doc in his last days, and thereby enhance the significance of Kendrick’s subsequent reminiscences. Smith also authenticates Doc’s heretofore anecdotal last words, “This is funny,” and clarifies that the quotation attributed to him by Kate, “Well, I’m going just as I told them the bugs would get me before the worms did,” closely approximates her reaction, “The worms won’t get Doc today.”

Many old-timers recalled that those who dressed Holliday for his funeral claimed to have found old scars from the gunfights of the past. Although Holliday’s body carried the scarred evidence of at least two wounds, Smith observed, “It was the first time I had seen the physical scars the consumption had left on his body.”

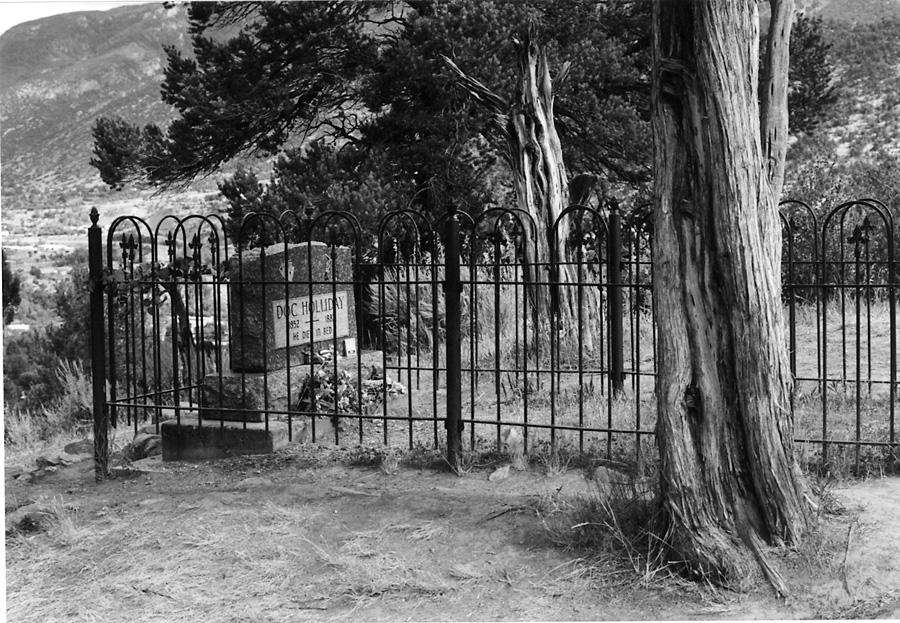

In recent years, controversy has arisen about the true site of Holliday’s grave. Charlie Smith recalled Holliday’s funeral “in a place called Linwood,” consistent with The Glenwood Springs Ute Chief report that “the remains were consigned to their final resting place in Linwood Cemetery.” The Aspen Daily Times (November 9, 1887) noted that he “was followed to the cemetery by a large number of kindred spirits,” and J.I Burdge, who acquired J.C. Schwarz’s undertaking parlor in 1911, recalled that as an 11-year-old boy he “followed the hearse up the hill [authors’ emphasis].” Other witnesses recalled that his was the second grave within the cemetery, near that of Jasper Ward’s, an 1887 victim of the community’s periodic conflicts with the Utes. Asked to locate the site of Holliday’s grave in 1953, Art Kendrick placed it, to his satisfaction, in Linwood Cemetery, just west of that of Jasper Ward’s. The efforts at controversy notwithstanding, it is evident that the final resting place of John Henry Holliday is located in Linwood Cemetery, likely in the general vicinity of where his marker presently stands.

We also learn from Smith that Kate left Glenwood Springs the day following Holliday’s death, and then, only after preparing Holliday’s effects for shipment to his Georgia relatives. Smith’s account confirms Holliday family tradition that Doc’s possessions reached Atlanta, where his uncle, Dr. John Stiles Holliday, collected the trunk and its contents. In addition to clothes, the trunk contained a gold stickpin missing its diamond, a set of straight razors, a small knife, and several gambling devices. Significantly, the trunk contained no dental equipment nor the Colt mentioned by Charlie Smith.

Smith’s writing style, consistent with the serialized romantic novels that filled the pages of many late nineteenth-century newspapers, encouraged him to occasionally attempt to view the tragedy through Kate’s eyes, “helpless not being able to ease his pain.” Did Kate actually reveal her thoughts to Smith or did Smith let his imagination flourish? The answer matters not. Smith was in the room, and his account of Doc Holliday’s final struggle, deemed in 1899 to serve as the standard account of the dentist’s last days, again assumes that importance.

Karen Holliday Tanner is related to Doc Holliday and is the author of Doc Holliday, A Family Portrait (University of Oklahoma Press). Her biography of outlaw George Musgrave, co-authored with her husband, John, will be released next year by the University of Oklahoma Press. An experienced writer, Tanner has written for True West, Wild West, WOLA Journal, and the NOLA Quarterly.

Clifton V. Brewer, a Sulphur, Oklahoma native, has had an interest in history for many years. He discovered this article in a trunk belonging to his great-great-grandfather (Lundsford Shockley), prompting him to research his family history. Brewer developed his interest in Doc Holliday after reading Tanner’s book.

Photo Gallery

– Author’s Collection –

– Courtesy Frontier Historical Society Museum, Glenwood Springs, CO –

– Courtesy Frontier Historical Society Museum. Glenwood Springs, CO –

– Author’s Collection –

– Courtesy of the Denver Public Library Western History Department –