I started collecting because I caught the bug—first reacting to the images, then to their context and history, and finally to the process of extracting the embedded stories that they contain.

I started collecting because I caught the bug—first reacting to the images, then to their context and history, and finally to the process of extracting the embedded stories that they contain.

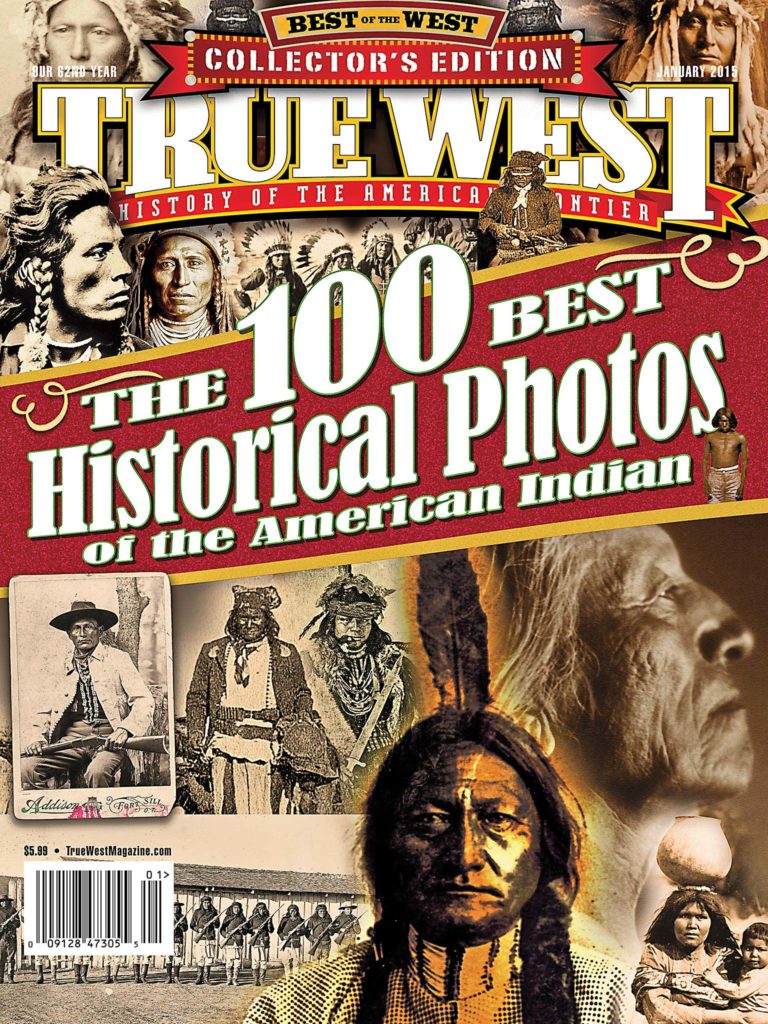

I got my passion for collecting American Indian photos because they provide a window into another culture, particularly in those photographs made soon after contact with “civilization.”

My first original photograph was a daguerreotype portrait, circa 1850, that I found in a flea market in the 1970s.

The one that got away is a great, but painful, memory. In the pre-Internet days, back in the days of phone bids, I was bidding on a half-plate tintype of a military band camped at the original location of Arizona’s Camp Verde in the mid-1860s. I was neck in neck with what looked like the only other bidder, and then got only busy signals, I couldn’t get through for over an hour and a half. The bidding had been cut off. I never did find out who got that wonderful image.

A recent acquisition is a stereoview of an unknown ranch building taken by Charles Farciot, circa 1878. It shows a group of white pioneers and American Indians, and was likely taken between Charleston and Globe, Arizona.

My favorite Western writer is Dan L. Thrapp.

Don’t get me started on fakes, forgeries and willful misattributions.

The best Western movie ever is 1952’s High Noon.

History has taught me that old photographs contain patterns and relationships, and occasionally a group of related images pops up that reveals both and brings the past to life.

A photo has to have a story—the better the blend of age, format, image, provenance and story, the more interesting the image, be it a daguerreotype, stereoview, postcard or snapshot.

The best way to take care of a vintage photograph is to scan it, put it in an archival sleeve and preserve it in the best collection based on topic and format.

The most interesting pioneer photographers are Dudley P. Flanders and George Rothrock, two who continue to amaze me, as I grow fonder of their images

The strangest pioneer photographer was Marcus T. “Cicero” Grime. He used the tagline, “White Buffalo Found Dead in the Photograph Gallery,” in his advertisements. He, his brother, Lafayette, and Curtis B. Hawley robbed a Wells Fargo & Co. stage outside of Globe, Arizona, in August 1882. Cicero barely escaped being hanged by vigilantes and was subsequently sentenced to 21 years in the Yuma Territorial Prison—bringing an end to his photography career.

Historical research requires passion, heart, perseverance, luck and a smattering of serendipity.

My mother always told me, “You and your grandfather are always digging around old stuff—it will never get you anywhere.”

Photographs can teach us about ourselves by allowing us to look back at our history, by giving us patience in the hunt and providing a great therapy, a pleasant black hole to fall into that is almost impossible to escape.

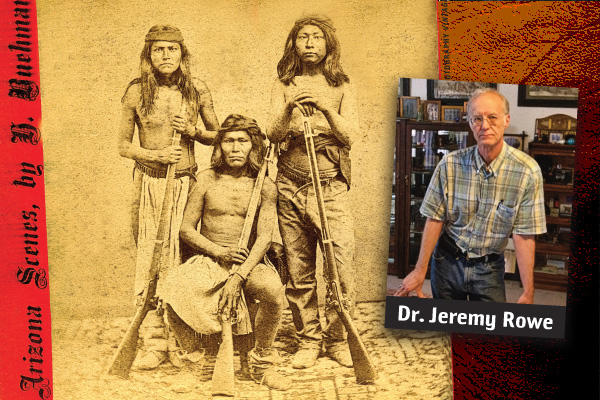

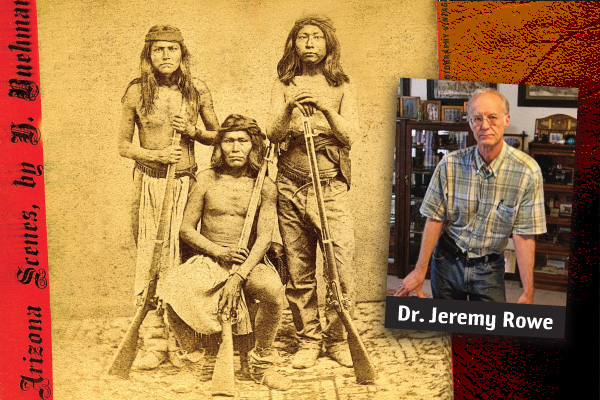

DR. JEREMY ROWE, VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHY HISTORIAN

Dr. Jeremy Rowe has collected, researched and written about 19th-century and early 20th-century photographs for more than 30 years. He has written several books and articles on the history of photography, and has curated museum exhibitions and a permanent exhibit at the Talking Stick Resort in Scottsdale, Arizona. He is emeritus professor at Arizona State University and a senior research scientist at New York University.