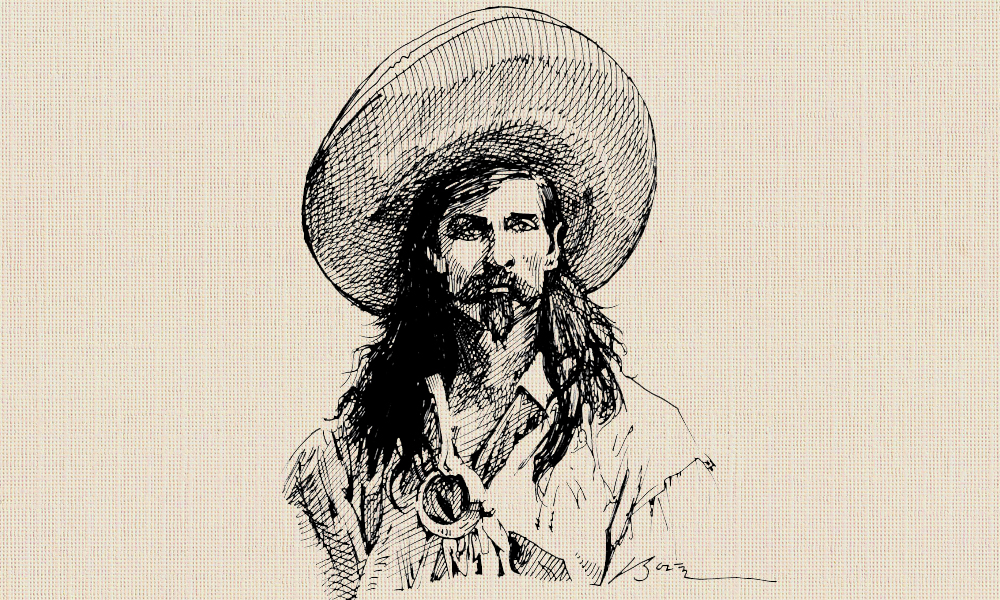

— Illustrated by Bob Boze Bell —

In the summer of 1882, Cibecue Apaches were smoldering over the U.S. Army killing Medicine Man Nockaydetklinne the previous year. That July, roughly 50 Apaches under Natiotish went on a wild spree—burning, looting and killing into the Tonto Basin.

Fort Apache troops followed in hot pursuit. On July 17, at Big Dry Wash, they caught up with Natiotish’s band. Outmanned and outgunned, the Apaches were routed in what became the last battle fought between the U.S. Army and the Apaches on Arizona soil.

But the Apaches had already forever changed the life of the Meadows family. On July 15, two days before, Natiotish’s warriors attacked the Meadows ranch. Barking dogs sent John Meadows Sr. to the creek to investigate when a shot rang out about 70 yards from his cabin. He threw up his arms, shouted, “Oh God,” and fell.

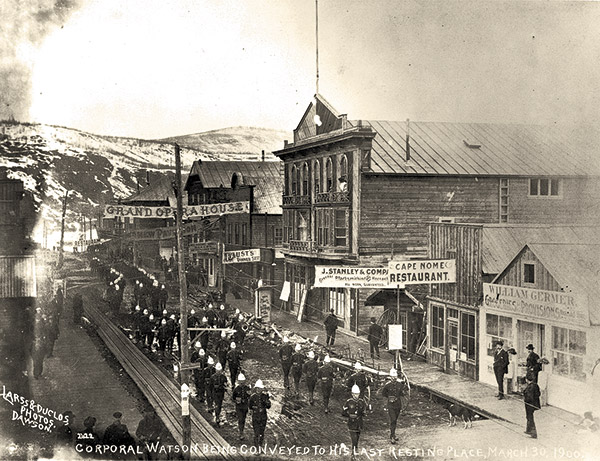

— Courtesy Yukon Archives, E.A. Hegg fonds, 82/290, #2513 —

Grabbing their rifles, Henry, 30, and John Jr., 29, ran to help their father, but gunfire wounded both. When the bleeding boys reached their cabin, Henry fell on the porch, unable to get up. Mother Margaret and nine-year-old Jake had to pull him inside.

Margaret and Maggie, 13, and James, 12, and family friend Sarah Jane Hazelton grabbed rifles and returned fire. Apaches peppered the cabin with gunfire until around 8 a.m., when firing ceased.

The family watched the Apaches herd the ranch’s cattle and horses. Many of these animals were later found needlessly slaughtered along the trail to Mogollon Rim. The Meadows family alone lost 200 head in the raid.

Margaret dispatched Johnny Grey to Pine Creek to notify Charlie. A few days earlier, Charlie had ridden there to guide an Army detachment from Fort McDowell to General Springs on top of the rim. When word of the tragedy reached him, Charlie rode hard toward home.

He arrived at the family’s ranch to find his father dead and two brothers badly wounded. The oldest son, Henry, died two months later. Charlie, 22, was now the man of the house.

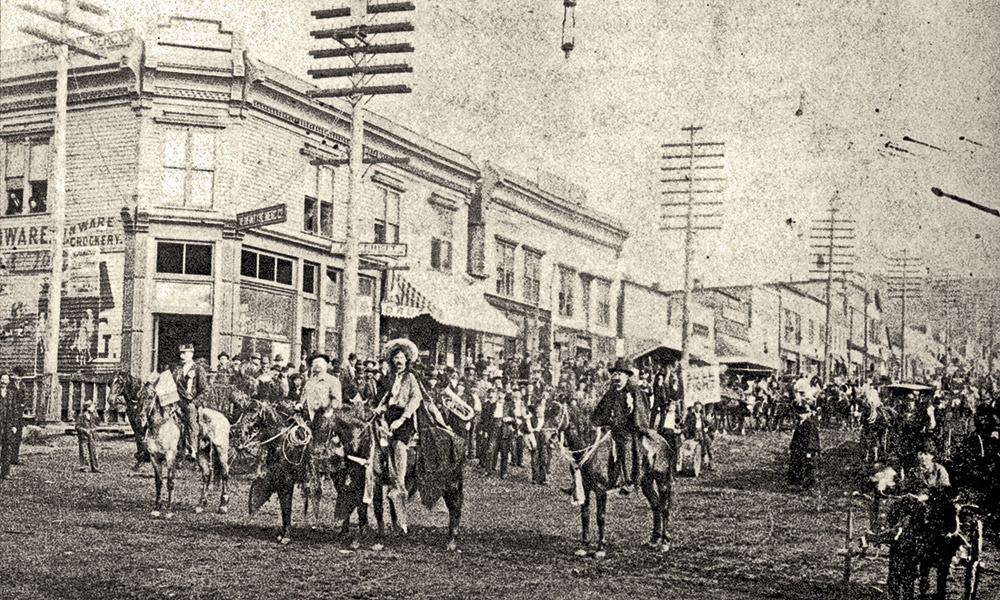

— Courtesy Yukon Archives, Robert P. McLennan fonds, 82/321, #6484 —

Stepping into a New Arena

Charlie was born Abraham Henson Meadows on March 10, 1860, along Elbow Creek, near today’s Visalia, California. He was the sixth of 12 children. His preacher and rancher father was a Confederate sympathizer; when Abraham Lincoln became the nation’s President, John changed the lad’s name to Charles.

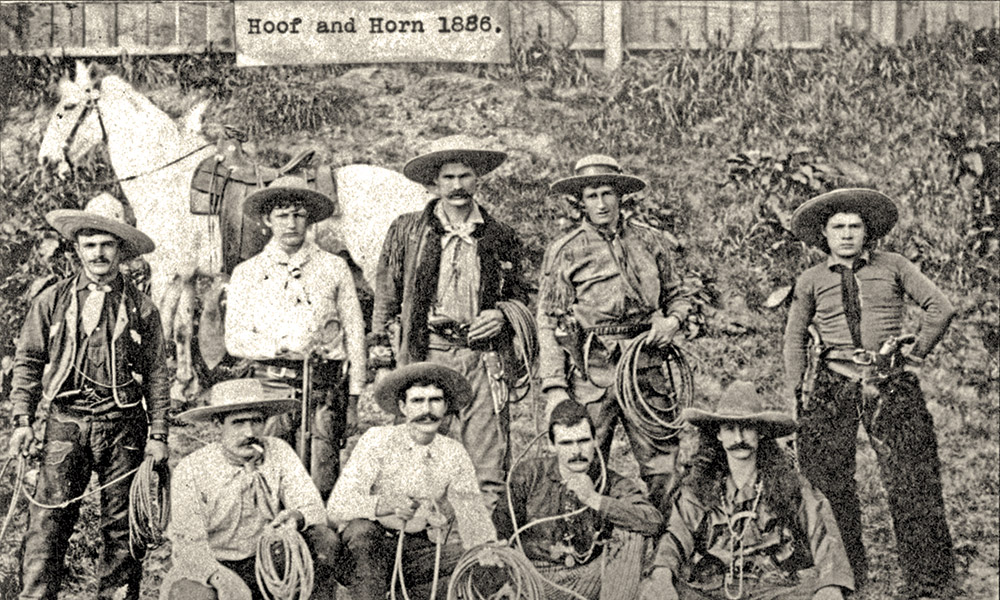

In 1877, the family settled on a ranch at Diamond Valley, north of Payson. In 1884, two years after Charlie lost his father and eldest brother on that ranch during the Apache Wars, Charlie entered a new arena. With John C. Chilson, he organized the Payson rodeo, which some historians credit as America’s first rodeo. Charlie also helped organize Prescott’s and Phoenix’s rodeos.

Charlie became a top steer roper in a territory that bred some of America’s best rodeo cowboys. He also loved to gamble, betting his rodeo purse on his skills. Most of the time, he won the pot.

At the Payson Rodeo in November 1888, while riding his white horse Snowstorm, Charlie won nearly every event, beating the future gun-for-hire Tom Horn at steer roping. The next year, Horn won.

Both cowboys caught the eye of William “Buffalo Bill” Cody, who was in attendance that day; he invited them to join his Wild West show. Horn turned down Cody’s offer, but Charlie headed to Cody’s ranch in North Platte, Nebraska, to discuss the details. Unable to find the showman, Charlie returned to rodeo, setting new records in steer tying in Prescott. Then he won again in Phoenix.

Yet Charlie had made up his mind to perform in a Wild West show. He needed to free himself from the responsibility of running the family ranch. He soon got that chance.

— Courtesy Yukon Archives, Bill Roozeboom collection, 82/313, #6279 —

No Business Like Show Business

On August 16, 1890, at August Doin’s, Charlie hosted a cattle gathering and a double wedding, for sister Maggie and Tom Beach, while her friend Julia Hall wed Charlie Cole.

Charlie allowed the couples to rope and brand all the unbranded calves on the Meadows ranch. By sundown, the newlyweds had gathered enough calves to start their own herds.

Unsaddled from his duty to the family ranch, Charlie left Payson to pursue his dream. In 1890, he traveled the world for two years with Wirth’s Wild West Show.

— Courtesy City of Vancouver Archives —

While performing in Australia with “Texas Jack” Omohundro, Charlie became enthralled with Marion Mae Murray, a runaway who had joined a circus.

Enjoying a romance too hot not to cool down, the two married aboard a ship in the Philippines. After 32 years of happy-go-lucky bachelorhood, Charlie had settled down.

Charlie met up with Cody in London, England, in 1892. He had long dreamed of joining Cody’s troupe, but Marion was opposed. She issued an ultimatum: “If you go, our marriage is over.”

Neither knew it at the time, but Marion was pregnant.

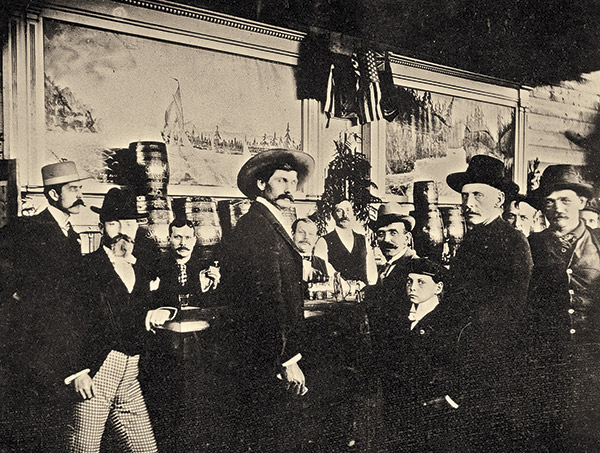

On August 10, Charlie joined Cody at a gala party for Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World. The celebrants included performers with colorful nicknames “Pony Bob” and “Cowboy Kid.” Cody declared Charlie needed a show name: “Why not ‘Arizona Charlie?’” The rest is history.

— True West Archives —

Charlie toured Australia, Asia, Europe, Canada and Alaska, meeting luminaries who included Will Rogers, Jack London, Zane Grey, Rudyard Kipling and Annie Oakley. Charlie even performed before Great Britain’s Queen Victoria.

Wearing his signature red neckerchief and fringed buckskin jacket, his hair flowing to his shoulders beneath his broad-brimmed hat, the six-foot-six Charlie proved an imposing figure in the arena. In 1893, he started his own troupe, Arizona Charlie’s Historical Wild West.

During an 1894 performance at California’s Santa Cruz Fiesta, Charlie hired the ravishingly beautiful rider Ida Mae McKamish. He billed her Mae Melbourne, perhaps to honor a romantic tryst in Australia.

Mae was hopelessly in love with her knight in shining armor, but Charlie was enjoying bachelor life.

— True West Archives —

Klondike’s Flamboyant Showman

In 1898, Charlie and Mae set out for the Klondike to make their fortune in gold. Newspapers reported the two had married prior to the trip, but no records support this claim.

Charlie preferred performing to mining, so he opened the Palace Grand Theatre in Dawson in 1899; still in operation today, it will reopen after renovations this summer. The three-story theatre originally seated 2,200, and it had a stage large enough for Charlie to demonstrate his sharpshooting talents, sometimes with him on horseback.

Everyone agreed Charlie was the Klondike’s most flamboyant showman. He livened up a slow night by shooting a cigarette out of Mae’s mouth or targeting glass balls off the top of her head, from 25 yards away.

One of his star attractions was Kate Rockwell, better known as “Klondike Kate.” Charlie paid her $200 a week. Rockwell later said she earned another $500 a week “entertaining” her string of admirers after the show.

Stories vary on Charlie’s success as a Klondike Stampeder. Some say he came home with a pocketful of money, while others say he returned nearly broke.

By 1901, the Klondike boom was fading, so Charlie sold the Palace Grand. He traveled up and down the Pacific Coast to promote Wild West acts.

Yet Old Father Time was pickin’ his pocket. Determined to postpone the inevitable, Charlie took up residence with Mae in Yuma, Arizona Territory.

— True West Archives —

New Life for an Old Man

Never one to sit still for long, Charlie searched for lost treasure on Tiburón Island in Mexico. He also tried to purchase the island. Neither venture panned out.

In 1914, Charlie received the surprise of his life. He laid eyes on his daughter, also named Marion Mae. Her mother had kept the two apart by claiming her father was dead.

Charlie’s relationship with his daughter, coupled with Mae’s dislike of Yuma and her mainly living in California, led Mae to drift out of Charlie’s life.

Marion and Charlie bonded quickly. He took her on cruises and regaled her with stories of his adventuresome career.

Marion reunited her parents after 34 years apart. Scarcely recognizable, each sized up the other like prizefighters before a bout, wondering what could have attracted them in the first place. She must have asked herself, “Is this gaunt, leathery-faced old man the same tall, handsome, swashbuckling cowboy I fell in love with?” And he couldn’t imagine the matronly gray-haired lady as the beautiful blonde equestrienne he had married.

But the ice slowly melted. They enjoyed a cordial relationship the rest of their days.

Not ready to go on to his reward, Charlie believed Yuma’s dry climate would extend his life. He rode his horse into town from his ranch every day. Occasionally, he’d ride through the swinging doors of a saloon, leading folks to exclaim, “‘Arizona Charlie’ is still out there, sowing his wild oats.”

Charlie had seen the elephant. He was born during a snowstorm in a California town where it rarely snowed. He garnered rodeo championships on his horse Snowstorm. In Yuma, where no records show it had ever snowed, he was fond of saying, “It’ll be a snowy day in Yuma when they plant this old Hassayamper,” a term for the territory’s earliest pioneers.

“Arizona Charlie” died on December 9, 1932. On that day, about an inch of snow reportedly fell in downtown Yuma. Old-timers claim snow hasn’t fallen there since.

Joke on Posterity

Don Meadows, kin to “Arizona Charlie,” brought forth a belt buckle engraved with “Prescott, July 4th, 1886, Best Time 59½ Sec.” which so excited the Prescott Centennial Committee in 1964—did the self-proclaimed “World’s Oldest Rodeo” get its start two years earlier?

Then spoilsport and cowboy book writer Fay E. Ward confirmed his suspicion: the celebration in 1886 did not include a rodeo, according to the weekly Journal-Miner, and 59½ seconds was the same time “Arizona Charlie” tied a steer in 1888; the steer kicked loose, so “Arizona Charlie” was not awarded the time for his score.

Marshall Trimble is Arizona’s official historian and the Wild West History Association’s vice president. His latest book, out this April from History Press, is Arizona Oddities: A Land of Anomalies and Tamales. For further reading on “Arizona Charlie” Meadows, he recommends Arizona Charlie: A Legendary Cowboy, Klondike Stampeder and Wild West Showman by Jean Beach King.