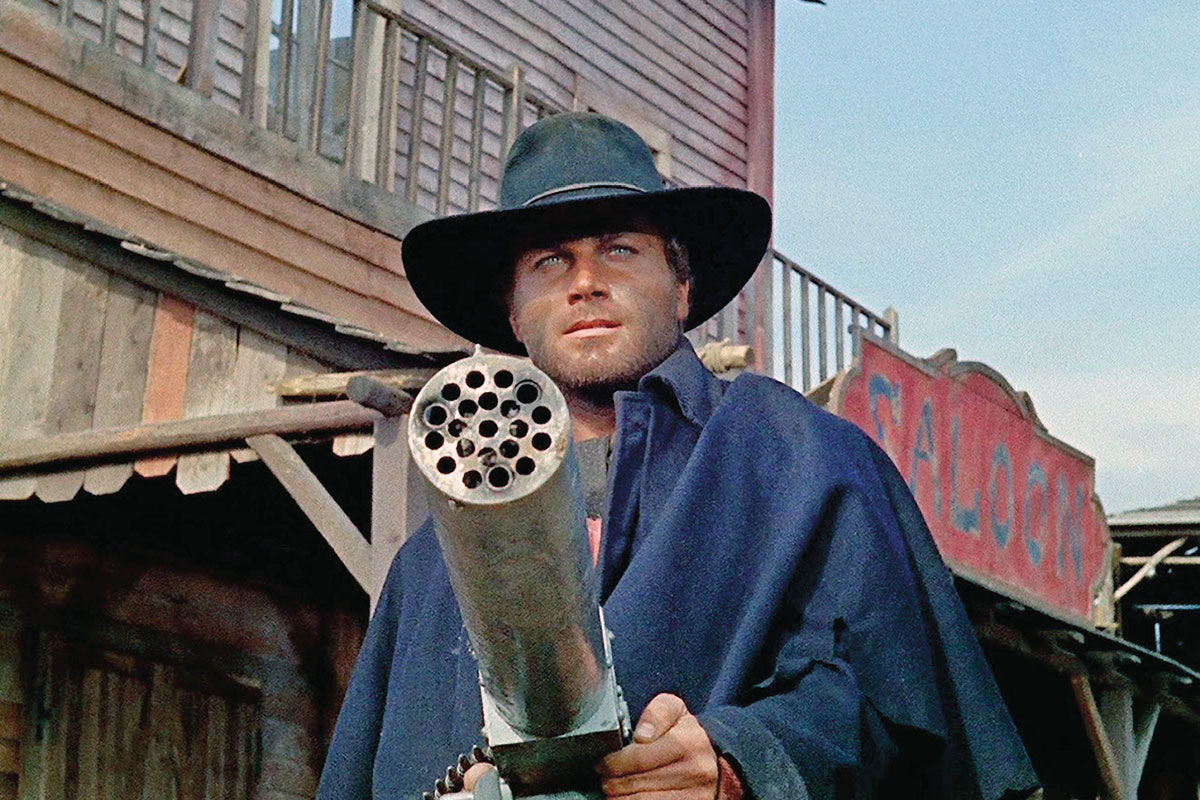

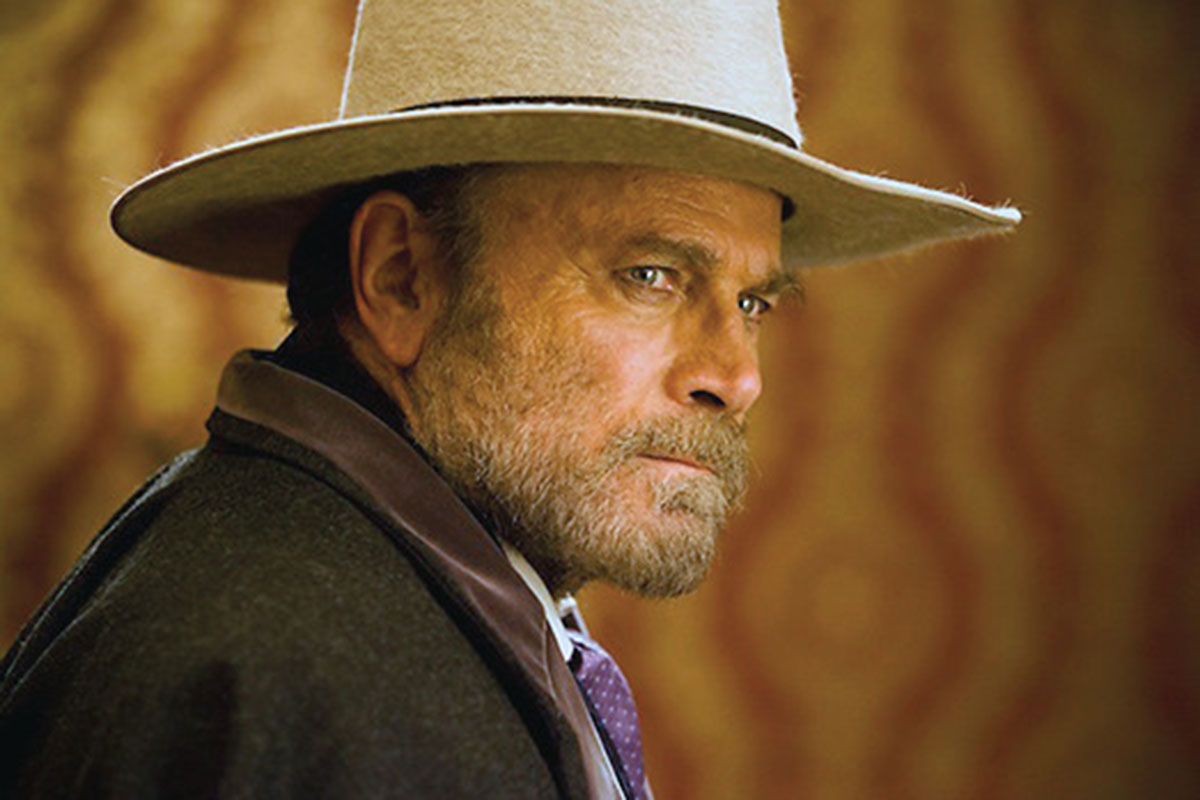

The term “Spaghetti Western” creates a specific image in most American minds: Clint Eastwood in a serape, gunning down a sea of bearded bandits. But in much of the rest of the world, Spaghetti Western doesn’t mean Eastwood; it means Franco Nero. In 1965, the Italian-born international star was spotted by director John Huston while working as set photographer on The Bible, and was quickly cast in the role of Abel. The rest is cinema history: the star of more than 200 movies and TV shows, Nero has appeared in every genre, and from 1990’s Die Hard 2 to 2017’s John Wick: Chapter Two, has played every sort of suave villain and hero imaginable. Notes Nero, “I think I’m the only actor in the world that played characters of thirty different nationalities.”

Before Django, and his career-making performance as the gunman who walks from one mud-drenched town to the next, dragging a coffin behind him, Nero had only played small roles in a fistful of films. But suddenly he was popular, he said, “because I was the discovery of John Huston.” Sergio Corbucci, known in Spaghetti Western circles as, “the other Sergio,” had already directed 25 movies when he offered Nero the role in Django. Nero said yes, but that wasn’t the end of it. “Corbucci wanted me, but one producer wanted Mark Damon, another one wanted Peter Martell.” Finally, they went to Fulvio Frizza, the distributor, with three photos, “and he looked at the three faces and he pointed his finger on my face. That’s how it happened.”

They got right to work, but not for long. “We did one scene before Christmas, but there was not a proper script. During the holidays, Sergio and his brother Bruno managed to do a scaletta, a treatment. After Christmas we managed to finish the film, but nobody thought it was going to be successful.”

They were wrong: “It was an incredible success all over the world.” To boost ticket sales, the name Django was added to many Nero movies. “I did a [gangster] movie in Sicily, and they called it Django With the Mafia. I did a movie called The Shark Hunter and the Germans called it Jungle Django.”

Because of the rapid pace of production in Europe versus the U.S., by the time The Bible opened, Nero had starred not only in Django, but in two more Westerns, two sci-fi movies, and was in the U.S. playing Lancelot to Vanessa Redgrave’s Guenevere in the musical Camelot. Appropriately, Nero and Redgrave would marry, although not until 2006.

Meanwhile, without strict copyright laws, anyone could put Django in their title, spawning easily a hundred imitators. Nero was not interested in returning to that role. “Laurence Olivier said to me, ‘Do you want to be a star or a good actor? To be a star you have to do one movie a year, like Americans do, and the movie has to be a commercial success, and they do always the same role. Or do you want to be an actor? Your long career will be up and down, but you get the fruits.’ I followed his advice.” Throughout the 1960s,’70s and ’80s, Nero would average three to five films per year, maybe a Western every couple of years. Nero would finally return to the character two decades later, in Django Strikes Again, filmed not in Spain, but in Colombia.

Although usually working with a largely European cast, Nero has enjoyed working with many American actors. “My favorite was Eli Wallach. I put him in six or seven of my movies in Europe. Another one was Tony Quinn. When my real father died in 1984, he said, ‘Don’t worry, from today on, I will be your dad.’ From that day I called him dad and he called me son. It was a great relationship.”

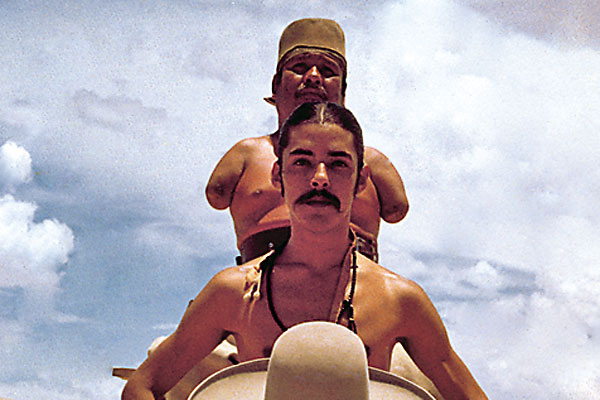

It was while making Deaf Smith & Johnny Ears, a film about the Texas Republic, that Nero connected with director Enzo Castellari. “He wanted to offer me a movie. But he looked like a boxer with muscles. I said to myself, I will never work with this guy.” Nero was in negotiations to co-star with Joanne Woodward in another film, but the director wanted a different actress. “I said no way; I don’t feel like doing the movie. He said, ‘I know why, I heard that Enzo Castellari just offered you a movie. Castellari is nobody; he is nothing.’ He said such terrible things about him that, the next day, I accepted Castellari’s movie.” They’ve collaborated on more than a dozen films since then.

Franco Nero finally became a Western star in the U.S. in the 1980s, when many of the 600-plus Spaghetti Westerns made between the mid-1960s and mid-1970s were suddenly released with the explosion of home video. Jonathan of the Bears, which Nero and Castellari shot in Russia in 1994, would be his last Western until Quentin Tarantino featured him in 2010’s Django Unchained.

And now there’s more to look forward to, with a sequel to Django in the offing. “Django Lives is a great script from John Sayles,” the Oscar-nominated writer/director of Lone Star. “Django is old now, but he managed to survive. He’s even stronger, you understand? Cross your fingers, maybe we’ll do it this year.”

Henry C. Parke is a screenwriter who has done audio commentary on four Franco Nero Westerns, and blogs about Western film and TV at HenrysWesternRoundup.blogspot.com.