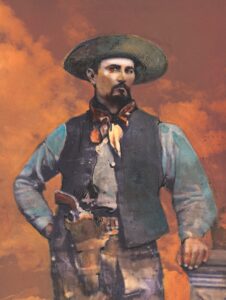

A look back at the legendary Texas cowboy who transformed the American Southwest

He almost single- handedly created the cattle industry, invented the chuck wagon, was an innovator for modern irrigation, helped save the buffalo from potential extinction, fought Indians, befriended Indians, scouted the plains, hauled freight, hanged rustlers, saved lives, kept his promises, founded the first ranch on the Texas Panhandle, is considered by some to have been the first Landman, and posthumously served as the inspiration for Larry McMurty’s lead character “Captain” Woodrow F. Call in the author’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, Lonesome Dove. Few men could have boasted of having blazed such an impactful trail across the American West throughout their lifetime. While the “Father of the Texas Panhandle” rarely gloated over his own accomplishments, True West is only too happy to celebrate the extraordinary life and achievements of a true colossus of the frontier. Was “The Colonel” the original man of vision? Yes, a hell of a vision.

Charlie’s exploits over the next 70 years would—and have— filled volumes. During his youth, Charlie, like all Texas immigrants, lived within the menacing shadow of the Comanche nation. Clashes between Americans and Comanches were shockingly brutal, even by the standards of frontier warfare. The Comanches, once the undisputed masters of the Texas Plains, found themselves pushed farther northwest, and the clashes between Indians and Whites became more frequent. Having no army to protect them, Texans often formed their own militia. Goodnight joined a group of Texas Rangers captained by one Jack Querton, signing on as a scout. “First, [to be a scout] a man must be born a natural woodsman and have the faculty of never needing a compass except in snowstorms or darkness,” he later recalled. “I’ve never owned a compass.” By his early 20s, Charlie was a more capable scout and guide than just about any of his fellow rangers.

In 1860, Charlie proved his worth in resounding style when finding a trail leading to a Comanche camp on the Pease River, where Cynthia Ann Parker—taken by the Comanches when she was only nine—was living. Charlie guided a company of rangers to the camp, took part in the attack, and recaptured Cynthia. Goodnight could not have known it at this time, but this action was to have important consequences later in his life.

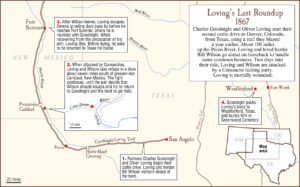

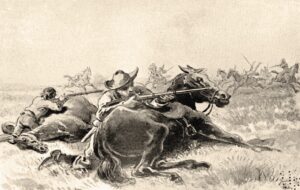

The cattle business was in chaos by the final year of the Civil War. While Comanches ran off an estimated 2,000 head of cattle in 1865, Charlie Goodnight found a new range along Elm Creek in Throckmorton County. As the market for cattle in Texas was in the doldrums, Goodnight and his fellow cowmen sought a better return for their beef from the army posts and Indian agencies in New Mexico. Goodnight, Loving and 18 other drovers (including the eventually infamous Clay Allison) pushed a drive from Fort Belkamp to the Pecos River and then north to Fort Sumner, where the U.S. government bought beef for the reservation Indians at a healthy price of eight cents a pound.

That cattle drive made history. The path they cut through became known as the Goodnight-Loving Trail, destined to become one of the most frequently trod cattle highways in the Southwest. The hands usually ate what they could carry and catch, like dried beef and hardtack. On that drive, Charlie invented the chuck wagon, which allowed the drovers to enjoy a hot meal for the first time. In one stroke of genius, he gave the world the food truck and Meals on Wheels.

The boys made two more drives along this trail, and the third one proved fateful. Loving was wounded in a fight with Comanches and died shortly after. Charlie honored his commitment to Oliver. He had Oliver’s body brought back to his home in Weatherford and told the family they would continue to receive a share of the profits. Intrigued, the greatest of Western novelists, Larry McMurtry, used Charlie and Oliver as models for Woodrow Call and Gus McCrae.

While Texas suffered a sagging postwar economy, Goodnight was expanding his business, contracting to deliver herds, some of them belonging to well-known names such as John Chisum. Some of his cattle drives went as far as Colorado, and even Wyoming. In 1869, Charlie built a ranch, the Rock Canyon, five miles from Pueblo, Colorado, the only ranch he built outside Texas. The Rock Canyon expanded to encompass several cattle lines and ranches, and in 1869, Charlie and his hands even found time to build an architecturally significant stone barn which still stands today—all that remains of Charlie’s Colorado empire.

The new decade marked an important event in Charlie’s life. In July 1870, he married the sweetheart from his early years, Mary Ann “Molly” Dwyer, who had become a schoolteacher in Weatherford. The marriage was no small event. The couple traveled to the home of Molly’s family, Hickman, Kentucky, and returned to Rock Canyon, where they lived until 1875. The Goodnight business was thriving. Charlie, working with John Chisum, cleared a profit of $17,000 in 1871 alone.

A progressive farmer, Goodnight was among the first to use modern irrigation for his farms and helped found the Stock Growers Bank of Pueblo, even becoming part-owner of Pueblo’s new opera house. The present was bright, and the future looked even brighter. But his ranges were overstocked, and the depression of 1873 caused him to lose most of his enormous holdings. Never at a loss for new ventures, he looked for an untouched grassland to feed his remaining cattle.

Charlie was still shy of this 30th birthday and had already lived more of a life than most men on the frontier would ever know. He was just getting started, as the loss of most of his holdings was simply a challenge to start over. “Better to lose your fortune than to lose your honor,” he later reflected.

Charlie sent Mary Ann to stay with relatives in California while he set out to rebuild his business. Once hostile Indian tribes had been defeated, the Panhandle was ripe for cultivation. Goodnight settled on Palo Duro Canyon. His devotion to the Panhandle lasted throughout his life. After losing a lawsuit, he proudly explained, “It cost me a lot of money, but we upheld the honor of the Panhandle.” His negotiating skills were put to good use when he sat down with the biggest sheep rancher in the Panhandle, Casimero Romero, and drew up an agreement which divided up nearly all the stock-growing land of northern Texas. Romero and the other pastores had the area around the Canadian River (which cuts across the northern handle), while Goodnight and his associates had sole use of the canyons, grasslands and headwaters of the Red River.

A non-judgmental businessman, Goodnight hired Nicholas Martínez, a former Comanchero–trader from northern New Mexico and West Texas who often dealt in illicit activities that most respectable Hispanics and Anglos avoided. Martínez knew the old trails and canyons used by the Indians and proved an asset for Goodnight and his new cattle outfit, including a young Englishman named James T. Hughes, whose father, Thomas, was well known in Victorian England as the hugely popular author of Tom Brown’s School Days.

Within the bounds of what is now Palo Duro Canyon State Scenic State Park, Charlie and his crew built a dugout out of cottonwood and cedar logs. Comanches had left some lodge poles behind, and the cowmen used them for rafters. Farther to the south, they found a canyon floor that widened out for more than 10 miles. Charlie supervised the building of a three-room ranch house. Having no nails, they had to notch the ends to fit each other in the manner of Lincoln logs. Corrals for their stock soon followed.

In 1877, Goodnight launched the JA Ranch in a five-year contract with John Adair; the deal made Charlie both co-owner and the resident manager of the ranch. Later, he extended his agreement with Adair for six more years. From the JA he led a herd along the Palo Duro-Dodge City Trail to the nearest railhead. The Queen of Cowtowns, Dodge City, Kansas, was a town where visiting cowboys could have a good time but within the boundaries set by Wyatt Earp and Bat Masterson. The JA was the first large cattle ranch in Texas. It is still running—the oldest cattle business in Texas—and is still owned by the descendants of John Adair.

A hundred years of movie and TV Westerns— John Wayne in Red River, Tommy Lee Jones in Lonesome Dove and Lorne Greene in Bonanza all come to mind—have told us that on the American frontier in the 1860s and ’70s, for ranchers to survive, they had to use force. In the movies, the invisible force of manifest destiny was backed by the latest repeating rifle and revolvers. The reality was somewhat different. Faced with potential enemies on all sides, ranchers keen on survival in that time and place had to be masters of diplomacy. Charlie Goodnight was blessed with resilience and a shrewd intelligence that manifested itself in negotiating skills which Talleyrand himself would have envied.

Charlie needed those qualities to deal with men such as Dutch Henry Born, the nemesis of Texas ranchers called by some historians “the biggest horse thief in the American West.” Legend has it Dutch was so good that he once sold a sheriff his own stolen horse. Charlie dealt with the Dutch Henry threat by meeting it head on, not with a Winchester, but with diplomacy. Setting up a meeting with Born and his gang near Fort Elliott, he made a deal with the outlaw to keep the rustlers north of his land, sealed with whiskey and a handshake.

Bison herds were considerably down in the late 1870s, and Indians who were otherwise peaceful began raiding ranches. Ever the negotiator, Goodnight met with Quanah Parker, the last chief of the Quahada Comanches. Charlie agreed to provide bison meat every other day if the tribe did not disrupt the operations of the ranch. The agreement not only held, but it was the beginning of a lifelong friendship between Charlie and Quanah, the son of the White woman he had rescued from a Comanche camp in 1860.

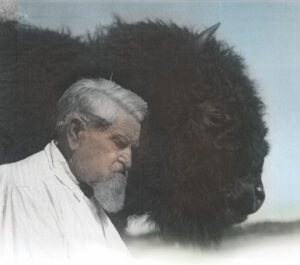

In 1877, Goodnight bought a herd of nearly 100 Durham bulls, the first to be bred in the area. He also tested crossbreeding Angus cows with bison, creating “cattalos.” Worried about the possible extinction of the bison, Mary Ann gave Charlie the idea to breed them as domestic animals. Today, the descendants of these bison can be seen at the ranch as well at the Official State of Texas Bison Herd in Caprock Canyons State Park. In 1880, he organized the first stockmen’s association in the Panhandle, which protected the cattle by policing trails, and running out thieves and outlaws.

Meanwhile, John Adair worked to expand the JA Ranch into a large operation. He succeeded beyond the expectations of either man. By the time of Adair’s death in 1885, the JA had grown to more than 1,300,000 acres,with well over 100,000 head of what one historian called “Goodnight’s carefully bred cattle.” In addition to co-owning the largest ranch in Texas, Charlie saw to it that it was also the most up-to-date. He was the first rancher in the Panhandle to irrigate his farmlands, thus creating a rich new stream of income by establishing permanent ranges on his land.

In 1887, Charlie sold his holdings in the JA Ranch and moved north to create the Goodnight Ranch. He and Mary Ann settled there near the town named for him, building what is now called a Folk- Victorian two-story house. The house stands in the Duro Palo Canyon State Scenic Park; it has been restored and is open to the public. As Charlie approached retirement, he looked back on his life on the frontier: “If all the good luck and all the bad luck I’ve had were put together, I reckon it’d make the biggest damned pile of luck in the world.”

With the frontier now tamed, the years of Charlie’s adventures came to an end, but not his business ventures. In 1890, he invested in gold and silver mines in Mexico, which failed, proving to be the crypto of its time. He and Mary Ann had saved enough to finance Goodnight College in 1898. He continued breeding cattle, buffalo, elk, antelope and different species of prairie foul in enclosures which, for all intents and purposes, made him the creator of the first zoo in the entire region. Buffalo from his herd went to zoos in New York, Philadelphia, London and Paris. He and Mary Ann also began a wildlife preservation effort which put them in touch with the leading naturalists of the time. Charlie lent some buffalo to Quanah Parker’s people so the young braves could experience a buffalo hunt. He became friends with Pueblo tribe leaders in New Mexico and took their side in Congress in lawsuits involving land and water rights.

In their retirement, the Goodnights sold the ranch and moved to Clarendon, Texas. Mary Ann died in 1926. The void in Charlie’s life was soon filled by a 26-year-old woman from Butte, Montana, named Corrine Goodnight. Historians are divided to this day as to whether Corrine was a distant cousin. Perhaps the most incredible chapter in an incredible life occurred when the old cattleman, ready for one more drive, married Corrine on his 91st birthday. The odds of a woman named Goodnight seeking Charlie out would have to be astronomical. The odds of a 91-year-old man marrying a 26-year-old woman would make for odds somewhat higher.

Charlie Goodnight had found religion by the time he and his second wife, Corinne, were staying in their winter home in Tucson in December 1929. When his biographer J. Evetts Haley asked him which church he had joined, Goodnight had merely replied, “I don’t know, but it’s a damn good one!” The legendary “Father of the Texas Panhandle” probably found comfort in his faith during his final moments before dying from influenza at the age of 93 in Tucson at 5:45 on the morning of Thursday, December 12, 1929.

In 1955, Charles Goodnight was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City. It is hard to imagine why it took them so long to recognize a man who was entitled to be the first plaque on their wall. Charlie’s legacy was well expressed: “Known for transforming cattle drives from a hard scrabble frontier livelihood into the biggest business in the American West.”

Charlie surely smiled in 1995 when the great character actor James Gammon was cast as Charles Goodnight in the TV miniseries based on Larry McMurtry’s Streets of Laredo. In the end, Charlie had summed up his life better than any portrayal could: “It has been my aim through life to try to have the world a little better because I lived in it.”