Los Angeles lawman William Hammel tamed one of the West’s wildest towns with hard work and Horseless Carriages.

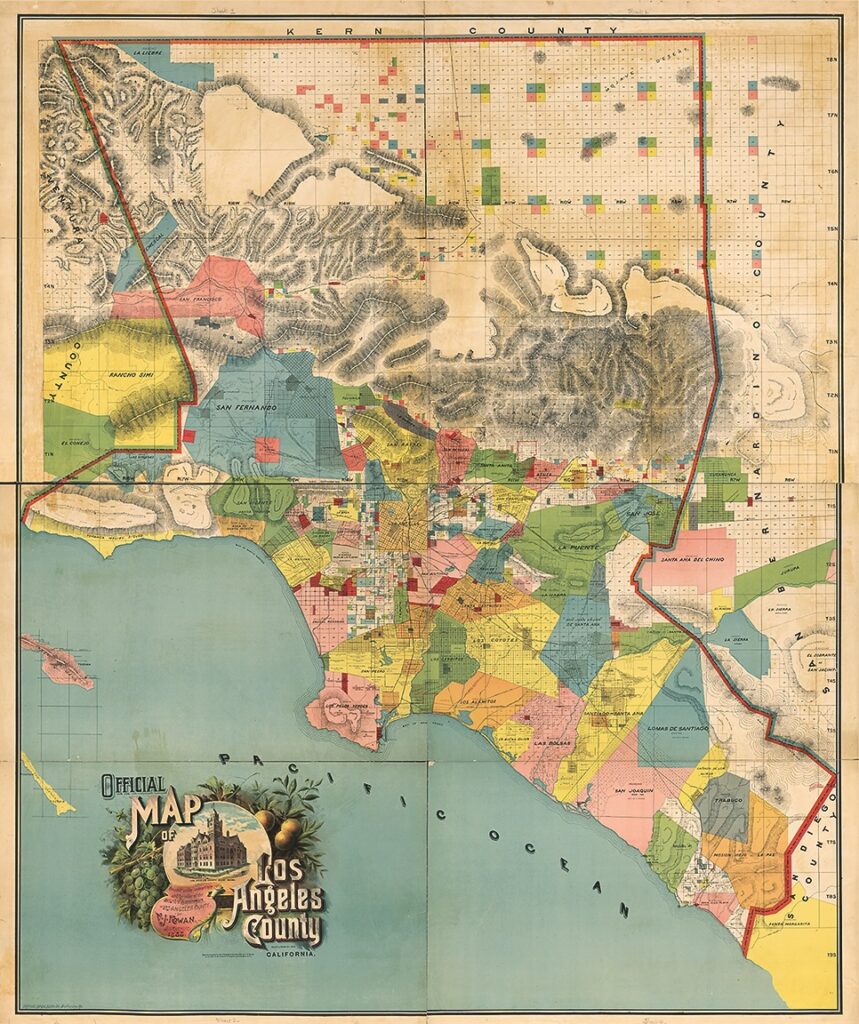

Los Angeles, California. Not everyone’s picture of a wild-and-woolly Western town—even though Wyatt Earp, who spent his last years there, claimed Tombstone in its heyday “wasn’t half as bad as Los Angeles.” Policing the City of Angels, and the 4,000-square-mile county of coastline, desert and mountains encompassing it, took a special breed of lawmen. Men like Billy Hammel.

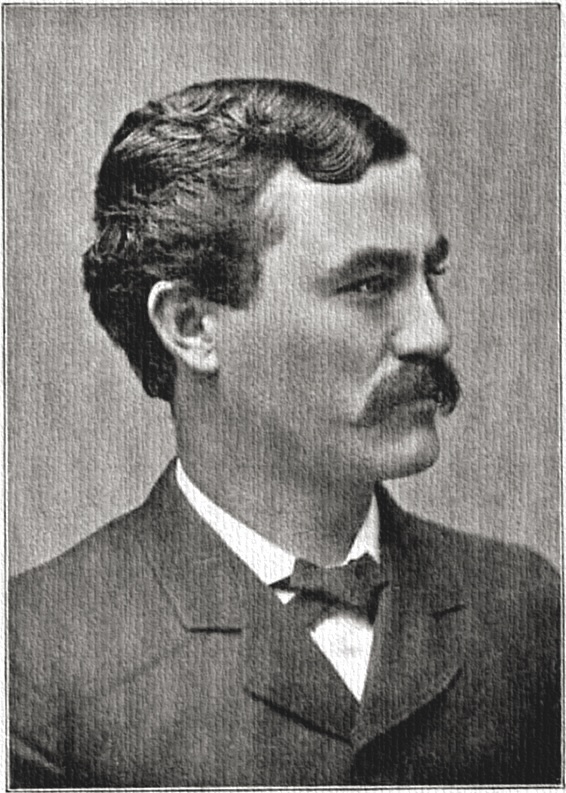

Native Angeleno William Augustus Hammel was born March 13, 1865. The son of a doctor and educated at Santa Clara University, young Billy—likely to his parents’ chagrin—took a brief stab at cowboying in Arizona. He soon returned to California and might have settled in the grocery business but for his brother-in-law, L.A. County Sheriff George Gard.

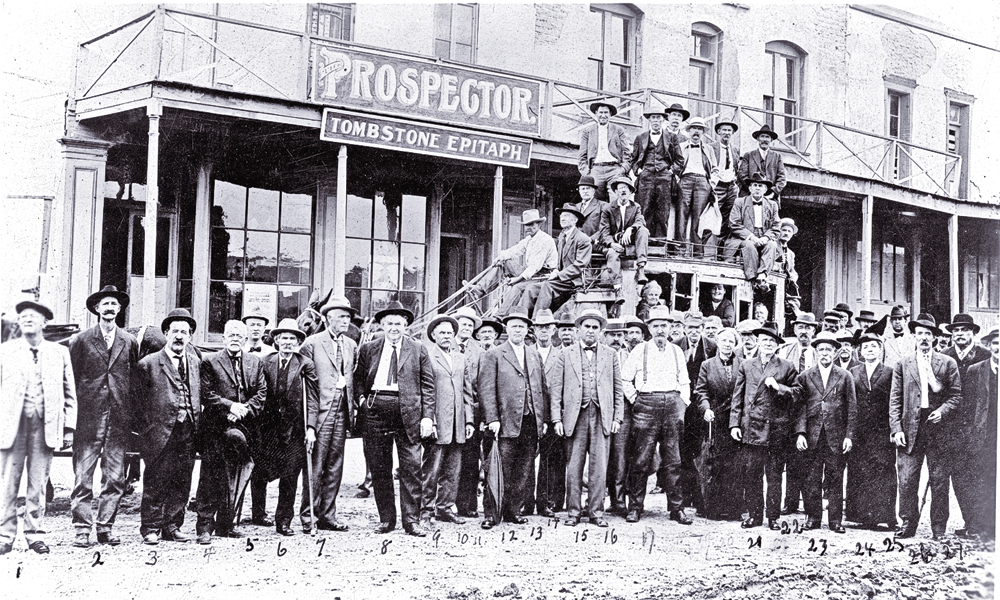

In mid-April 1885 Melcado Garcia, a notorious “horse-thief and desperado,” had traded gunfire with a deputy sheriff near the San Gabriel Mission. Gard swore in Hammel as a special deputy and sent him and boyhood friend Martin Aguirre, a county constable, on Garcia’s trail. They followed it northwest through the Arroyo Seco and, finding Garcia “wounded in bed”—the deputy’s bullet in his chest—30 miles away at San Fernando, captured him without further gunplay. Thus in true Old West fashion, Hammel embarked on a career spanning four decades, taking L.A. law enforcement from its horseback days to the mechanized 20th century.

A Badge Well Worn

Appointed a regular deputy, Hammel’s duties alternated between hazard and routine—arresting cattle rustlers, ferrying convicts to prison, serving papers. He was slightly wounded in a skirmish with another horse thief and stopped a runaway horse and buggy after a firecracker startled the animal. In 1889-90, with Martin Aguirre as sheriff, Hammel further distinguished himself, helping capture a fugitive who’d shot and wounded Aguirre, and arresting a fugitive in an 1872 Texas murder. Aguirre’s successor, E.D. Gibson, assigned Hammel to the district attorney’s office as one of its first detectives.

Having built a solid reputation, Hammel ran unsuccessfully for sheriff in 1892 and 1894. The third time proved the charm. Elected in November 1898, the new sheriff started with a rare act for a politician: keeping a pledge. For the local Afro-American League’s campaign support he’d promised to appoint a Black deputy—the first in L.A. County. Hammel made a solid choice in Julius Boyd Loving, who’d serve faithfully and fearlessly for nearly 40 years. Not joining Hammel’s team was Martin Aguirre, who’d gone north as warden of San Quentin prison. Still, it wouldn’t be the last time the two old law dogs hunted together.

Though Hammel proved a strict leader, firing a deputy in mid-1899 for extorting “license fees” from a female saloonkeeper, he retained some cowboy copper ways. “If you are insulted by a bully in the office don’t lick him there,” he warned in a staff briefing. “There are plenty of dark alleys.” He learned the frustrations of leadership in October 1899 when a new U.S.-Mexico treaty prevented him from extraditing murder suspect Juan Puebla from below the border.

To Serve and Protect

In January 1903, former deputy Will White became the new sheriff. Hammel spent much of the year eyeing upcoming openings for wardens at Folsom and San Quentin (Aguirre was vacating the post) but ended it in the running for another job. The Los Angeles Police Department badly needed reform, and several city fathers felt Hammel was their man. In April 1904, he became the second person to have served both as L.A.’s county sheriff and its police chief (the other was his brother-in-law George Gard).

Vowing to make L.A.’s police force “second to none in the United States,” Hammel answered complaints that “vice of every kind had full sway in the past” by directing raids on opium dens, proposing licensing to combat “crooked horse traders” selling diseased stock, and ordering a crackdown on “mashers” and “indiscriminate makers of goo-goo eyes” harassing ladies on the streets. In the latter cases, the L.A. Record reported, his orders implied that “it may be necessary for an ambulance to bring in the offender.” Looking forward, Hammel replaced a horse-drawn patrol wagon with an electric model, capable of 20 miles per hour, and doubling as an ambulance. He also urged upgrades to the receiving hospital—the city’s only emergency facility—which operated under LAPD’s umbrella.

Hammel dealt swiftly with misconduct; his first official act was suspending a patrolman for intoxication. He later relieved three officers for extorting protection money from prostitutes. But he rewarded diligence, supporting a plan devised by several sergeants for a relief association to assist sick and injured officers and provide burial expenses for line-of-duty deaths.

In November 1904 Hammel was himself accused of misconduct, by none other than the Mexican government. Receiving word that Juan Puebla—the murderer who’d eluded his extradition efforts as sheriff—was frequenting Campo, in the desert east of San Diego, Hammel and a police detective headed south. When they returned with the fugitive in irons, Puebla cried foul, claiming Mexican ruffians had waylaid him south of the border and delivered him to the lawmen. “If the line between the two countries became dim or uncertain,” the L.A. Times unconcernedly remarked, “or was mysteriously moved a bit just to suit circumstances, it would not be strange.” Diplomatic kerfuffle aside, Puebla was convicted and packed off to San Quentin, and Los Angeles’s city dads reappointed Hammel for another year.

A July 1905 L.A. Herald spread headlined “Police Force is Model Army” praised Hammel’s leadership and detailed improvements on his watch. In further innovations, he upgraded the department’s telephone system to a central exchange, proposed a citywide alarm system, and owing to a plague of “scorchers” (speeders) on city streets, recommended examination and licensing of automobile drivers.

Despite praise from press and politicos, Hammel tendered his resignation in August. He was mum on his reasons, but friends and city councilmen cited frustration with meddling by the mayor. Whatever his reasons, Hammel’s trusted subordinate, Capt. Walter Auble, replaced him in October. By April 1906 he was back in the county sheriff’s race, and in November was elected to a four-year term.

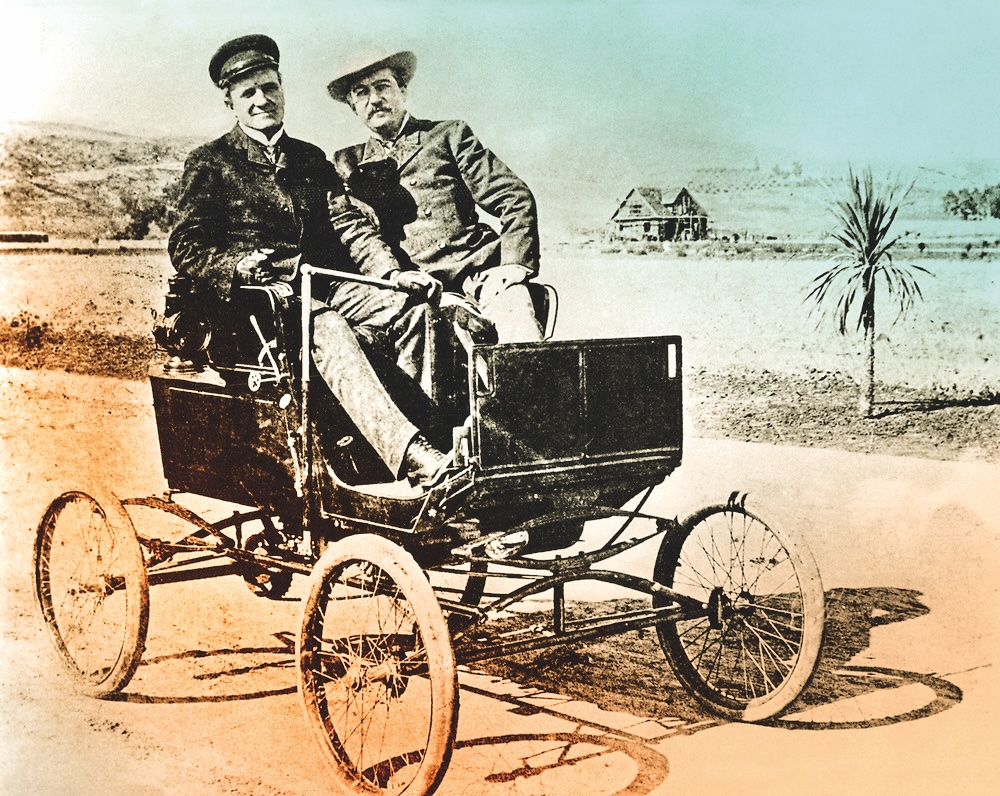

A Sheriff with Horsepower

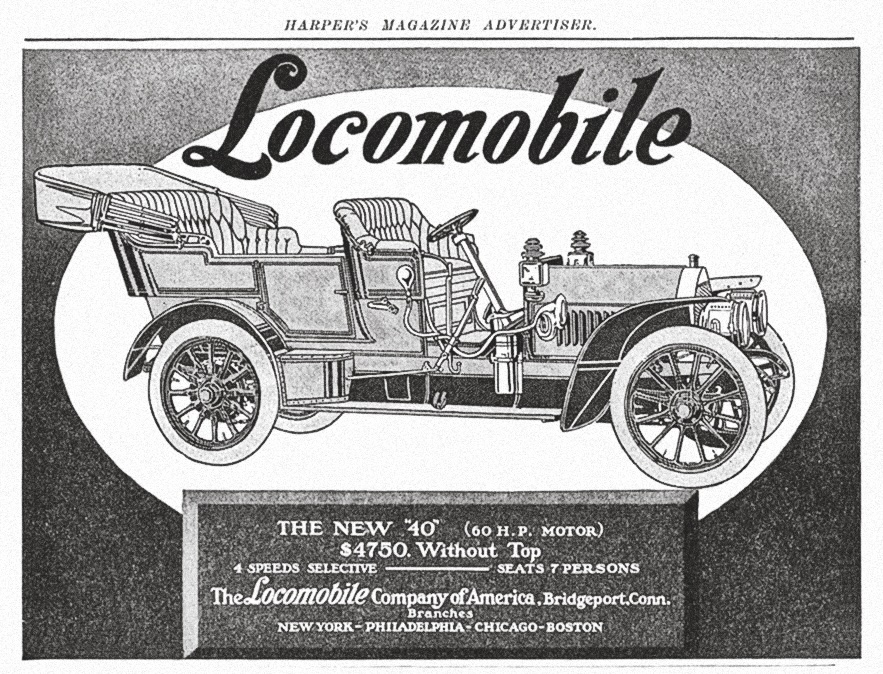

Back behind the sheriff’s star Hammel continued exploring new ideas, his greatest innovation being the introduction of motor vehicles. The Thor motorcycles he fielded allowed deputies “to answer hurry-up calls,” but he was best known for his personal vehicle—a specially outfitted seven-seater 1908 Locomobile touring car. With Deputy Billy Fryer at the wheel, Hammel and his “big red car” became a familiar, fearsome sight on the county’s streets and side roads; he was possibly the first Western sheriff to hunt crooks in an automobile. When robber Louis “The Rabbit” Willey broke jail in February 1908, Hammel and Fryer nabbed him within minutes. In May, with L.A. Police Chief Edward Kern riding along, they aided the hunt for the killer of Hammel’s LAPD successor, Walter Auble.

Courtesy J.R. Sanders, Harper’s Magazine

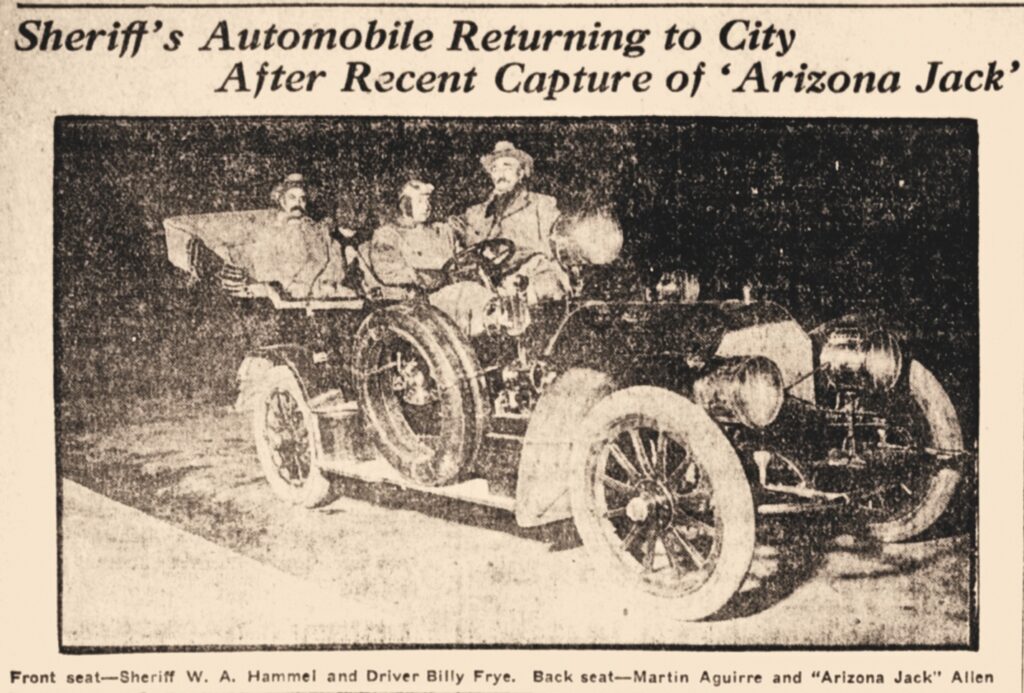

Hammel’s most high-profile vehicular pursuit came in January 1909. With Fryer and old pal Martin Aguirre—now his deputy—he scoured the county for a cowboy drifter named John “Arizona Jack” Allen, who’d shot and killed Deputy Constable Charles De Moranville at Newhall, in the desert north of Los Angeles. Crisscrossing 200 miles of rugged terrain, using Allen’s own dog to help track and twice cutting off his escape, the lawmen cornered their quarry at a ranch mere miles from the shooting site. Suspecting Allen was hiding in a barn, Hammel sent in the dog, and the pup’s overjoyed barking betrayed his master. When Allen scuttled from his hidey-hole and ran for the trees, Hammel threw down on him with a Winchester, and Aguirre snapped on the cuffs. In a jiffy, the big red car was shuttling Allen to the county jail.

Hammel’s 1907-10 term was also distinguished by his hiring of Eugene Biscailuz (later L.A. County sheriff), and his part in investigating the 1910 bombing of the Los Angeles Times building. Next term, he added yet another first to the sheriff’s department. Echoing the nepotism that kicked off his career, in 1912 Hammel installed the department’s first female deputy—his sister-in-law, Margaret Q. Adams.

In March 1913 Hammel’s Locomobile, having logged nearly 200,000 miles, was featured in a Times article, “Bad Ones Fear This Machine.” The “old red automobile,” said the paper, had seen more action and romance than any “galloping, foam-flecked steed carrying a frontier sheriff over mountain and desert in pursuit of desperate outlaws.” Buried in the piece was Hammel’s petitioning the county for “a more modern, high-powered car.” The auto, like the sheriff, was nearing the end of a long, colorful career. In November 1914 John Cline, sheriff from 1893-94, defeated Hammel for reelection.

Following William Hammel’s death on New Year’s Day 1932, his funeral’s honor guard included trailblazers Julius Loving, L.A.’s pioneering Black deputy, and Eugene Biscailuz, who’d been first superintendent of the California Highway Patrol and would become L.A. County sheriff in December, holding the job for a record 26 years. It was a fitting tribute for an old lawman who’d blazed some trails of his own.