JOHN MULLINS KILLED IN AUTO MISHAP

John Mullins, 40, formerly of Bozeman, Montana, died here today from injuries received when he was struck by an automobile at Wadsworth, 30 miles from Reno, last night.

Mullins, who had resided at Wadsworth for the last two years, was struck while he was crossing a highway running through town by an automobile driven by Arthur Dowwns, Fallon, Nevada. Mullins received a fractured skull and other injuries and never regained consciousness. He was brought to a hospital where he died.

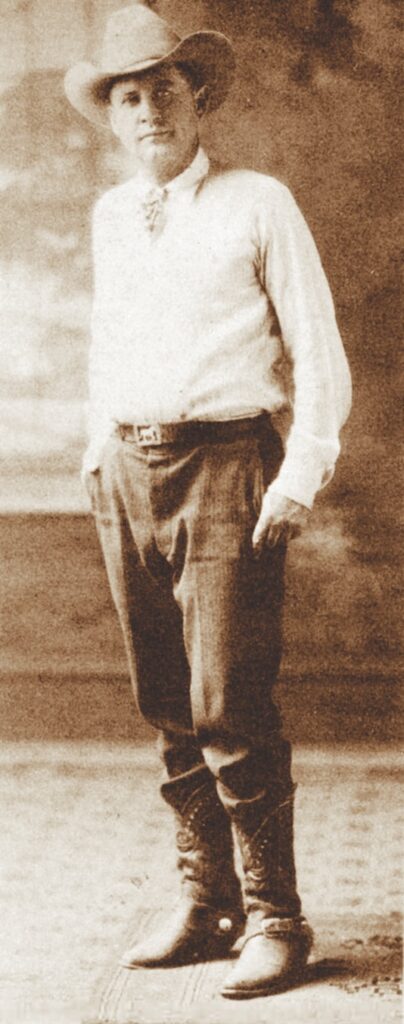

All images courtesy Walt Coburn unless otherwise noted

Within twelve hours every newspaper in the United States, Canada and Mexico printed the tragic news of the death of Johnnie Mullens, known nationally and internationally as the greatest rodeo arena director in the world. (The AP News had misspelled the name Mullins.) Johnnie Mullens, well known rodeo contestant, had served as arena director and furnished the livestock for the famous Tex Rickard Madison Square Garden Rodeo in New York City from 1924 to 1930. He became arena director for the Calgary Stampede in 1912, to put Calgary on the map as holding the first great rodeo in the world, and he held that job from 1912 until 1917. He was arena director of the Philadelphia Rodeo, and in Montana he was arena boss at the Bozeman, Deer Lodge, Livingston and Butte Rodeos. He also managed the rodeo arena at Couer d’Alene, Idaho; Kansas City, Missouri, Silver City, New Mexico; Tucson, Arizona; and many others throughout the country.

As a bronc rider and roper Johnnie Mullens contested in every large rodeo from Canada to Mexico City. He once worked with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and Miller Brothers’ 101 Wild West Show. He handled the famous Ringling string of bucking ·horses and rodeo stock.

The name of Johnnie Mullens was a byword in the rodeo world. As a boy and youth he punched cows for the biggest cattle spreads from the Indian Territory and New Mexico to Montana, the Dakotas and Alberta, Canada. Owners of the biggest cow outfits in the United States, Mexico and Canada, knew and liked the smiling, good-natured top bronc rider and cowhand. Every rodeo contestant worthy of the name called Johnnie Mullens his friend.

News of his untimely death spread throughout the West like a prairie fire driven by a strong wind. Cowtowns without newspapers or telegraph or telephone service heard the news by word of mouth. Even on remote cattle ranches the report of his death somehow reached the distant cow camps. And for those who called him friend, the news carried an impact of shock, deep grief and sorrow.

Thus the tragic word of the death of Johnnie Mullens and the frantic search to locate Mrs. Mullens (the former Ruby Shepard of Bozeman, Montana) kept the telegraph wires hot from Reno to all compass points.

Johnnie Mullens is one of the last of a vanishing breed of men, the old-time cowhand. Those old-time cowhands knew the meaning of loyalty to whatever outfit they worked for, and Johnnie worked for the best.

Those were the days of free grass and open range, before the cow country was fenced in by the homesteaders, who plowed up the old roundup trails and fenced in the waterholes. When a cowboy could swing a big loop without getting it fouled up on a fence post. The days before barbed wire.

The old-time cowhand was proud, independent, durable and tough as rawhide, seasoned and hardened to endure the hardships of a frontier country. That tough, hardy breed of cowhand was needed in those days of the frontier cattle country, and they fulfilled their destiny, left their mark in the Archives of Western history.

A couple of years ago, Johnnie’s horse got fouled up in a brush-concealed tangle of rusted barbwire. In the horse’s frantic scramble to free his legs from the entanglement, he came over backwards, pinning Johnnie down. When the horse finally scrambled to its feet, Johnny kicked his feet from the stirrups and rolled free. He wound up in the community hospital with a shattered pelvis.

“First time in my life,” Johnnie told me when I visited him, “I was ever laid up in a hospital. First time I ever got busted up.” And he was then seventyeight years old.

The doctors decided that Johnnie Mullens would never be able to ride a horse again. Seven months later he was back at the ORO ranch making a hand.

Then about a year ago, along about the Christmas holiday season, one morning early as Johnnie stepped into the house to eat breakfast, it happened again. Johnnie stepped on a small scatter rug that slipped out from under him and he wound up in the hospital with a broken hip, going from bed to wheelchair, to crutches, and then to a cane.

When I saw him recently he was walking around spry as a cricket in his shopmade high-heeled boots, with the short, bowlegged stride of a cowhand. He boarded a California-bound bus to visit his daughter, Colleen, and her family. After a few days in California he went to El Paso, Texas and Juarez, Mexico, to visit relatives and friends. He came back bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, with scarcely a limp, using ·a cane more for balance than anything else.

Right now the durable, indestructible octogenarian is back at the ORO ranch, where he still makes a cowhand wherever. a top hand is needed.

“I’ve been roundsidin’ long enough,” Johnnie told me just before he pulled out for the ranch. “Puttin’ on too much taller around the belly. A week or so a horseback is what a feller needs to get back in shape.”

Walt Coburn (1889-1971) was a prolific Western writer churning out a reported 600,000 words a year. Born in Montana and raised on a ranch, he started writing in the 1920s and was promoted as the “Cowboy Author,” he committed suicide in Prescott in 1971.