— True West Archives —

Poor Jesse James might not have been the victim of what amounted to state-sanctioned murder in 1882—or so many bad movies—if he hadn’t made that first career blunder in Gallatin, Missouri, in 1869. But how did the West’s most notorious bank, train and stagecoach robber get to Gallatin?

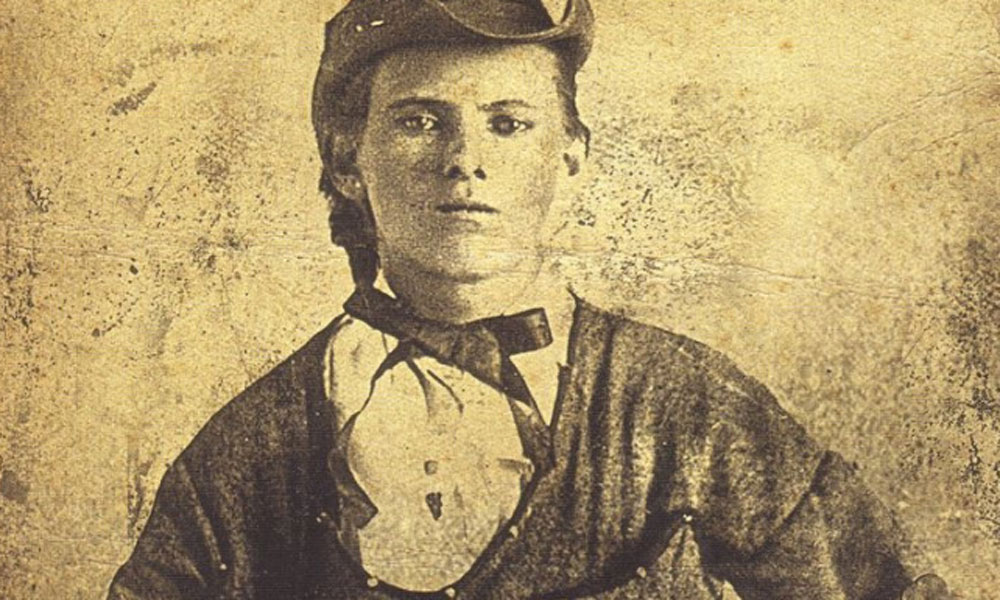

It starts at the family farm outside of present-day Kearney, Missouri, where Jesse Woodson James was born on September 5, 1847, and where visitors today can tour the museum, farmhouse and Jesse’s original grave at the Jesse James Birthplace Museum.

Jesse’s Kentucky-born dad, Robert James, became pastor at New Hope Baptist Church—now called New Direction Church—in Holt. Things might have turned out differently too, but in 1850, Robert James left Missouri for the California goldfields only to die of fever four months after arriving in present-day Placerville.

Then came the Civil War. Big brother Frank enlisted in the pro-Confederate Missouri State Guard, was captured during the Battle of Wilson’s Creek in April 1861 near Springfield (tour Wilson’s Creek National Battlefield), paroled, then broke parole and joined guerrilla William Clarke Quantrill’s Southern bushwhackers.

On May 23, 1863, pro-Union forces, looking for Quantrill, hoisted Jesse’s stepdad off the ground with a rope to make him talk. Legend says they also whipped 15-year-old Jesse with a rope. That eventually drove Jesse to join the bushwhackers, but the war was lost. When Jesse attempted to surrender in May 1865, he was shot through the lung.

— Photo courtesy of Johnny D. Boggs —

First Bank Robbery?

On February 13, 1866, the Clay County Savings Bank in Liberty, Missouri, (visit the Jesse James Bank Museum), was robbed of roughly $60,000 in gold, currency and bonds. The gang of 10 to 12 men also killed a 19-year-old bystander. Years later, the crime was chalked up to the James-Younger Gang.

But could Jesse—still recuperating from a bullet through his lung—have taken part in a robbery during a bitterly cold February day? Some historians put Cole Younger and Frank there, but the fact is we just aren’t certain.

William A. Settle, Jr., author of Jesse James Was His Name (1966), the first serious historical study of the thug, writes: “Actually, identification of the bandits is not simple. Those insiders who knew the facts talked little, and what they said was not always reported exactly. Moreover, people who could remember the events and who talked about them did not always have firsthand information.”

The same can be said for the robbery of the Alexander Mitchell and Company Bank on October 30 in Lexington, Missouri (Lexington Historical Museum), that netted four robbers $2,011.50. “This is quite the coolest and most daring robbery that has happened in this part of the State since the Liberty Bank Robbery,” the Lexington Register reported.

In his 1903 autobiography, Cole Younger wrote that “so far as I know [the Lexington job] was never connected with the Younger brothers in any way until 1880, when J.W. Buel published his Border Bandits.” I haven’t found any mention of Lexington in Buel’s book. Still, most historians don’t link this one to the boys.

— Courtesy Jesse James Birthplace Museum —

Not the James Boys

Two Missouri bank jobs the following year in Savannah (Andrew County Museum) and Richmond (Ray County Museum), later attributed to Frank and Jesse, probably weren’t committed by any Jameses or Youngers. The M.O. and outcome of the March 2 attempt to rob Judge John McClain’s private banking enterprise doesn’t point to the boys: Five or six bandits ask McClain for the key to the vault. When the judge refuses, he is shot, and the outlaws flee empty-handed.

In The Outlaw Youngers, Marley Brant calls this perhaps “the first ‘copycat’ robbery attempt.” Three ex-bushwhackers were reportedly arrested, including Robert Pope, who was identified as the man who wounded the judge.

Regarding the Richmond job on May 23, Jesse might be thankful that he and the boys weren’t there. The gang, numbering from 11 to 20, took some $3,500 from the Hughes & Wasson Bank. When they rode out, three citizens were dead. By that time, T.J. Stiles wrote in Jesse James: Last Rebel of the Civil War, “authorities were ready to strike when old Quantrill and Anderson men appeared on the list of suspects.”

Eight men were originally charged with the crime. A horse thief named Felix Bradley, who wasn’t charged, was lynched. Dick Burns and Payne Jones, were charged, were captured and were lynched. So was Tom Little. And Andy McGuire. And even Jim Devers, who was later arrested because he might have been involved. Allen Parmer, who was charged, luckily had an alibi.

(Jesse might not have taken part in this robbery, but Richmond’s two cemeteries are home to two important men in Jesse’s life—his Civil War commander Bloody Bill Anderson and Jesse’s assassin Robert Ford.)

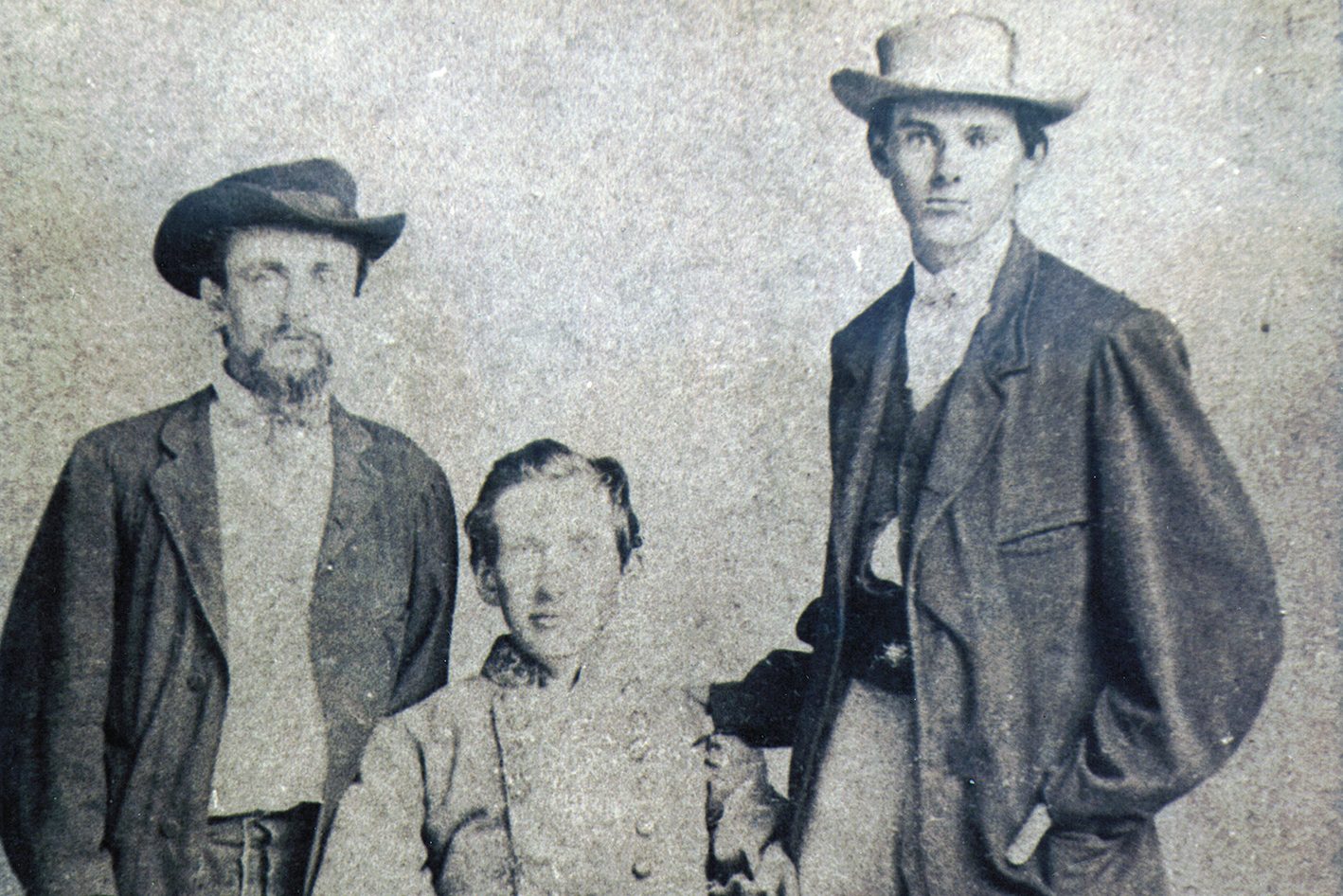

The earliest bank job that most likely can be credited to Cole Younger and the two James brothers happened in Russellville, Kentucky (take the downtown walking tour), when five to six men robbed the Nimrod & Co. Bank of around $12,000. The M.O. fit. Frank and Jesse had friends and family in Kentucky. One robber called himself “Thomas Coleman.” Two pals of Jesse and Frank, brothers Oll and George Shepherd, were suspected. George was arrested, identified and sentenced to three years in prison. Authorities shot and killed Oll Shepherd at his father’s house near Lee’s Summit, Missouri.

— Photo courtesy Johnny D. Boggs —

The Real James Gang

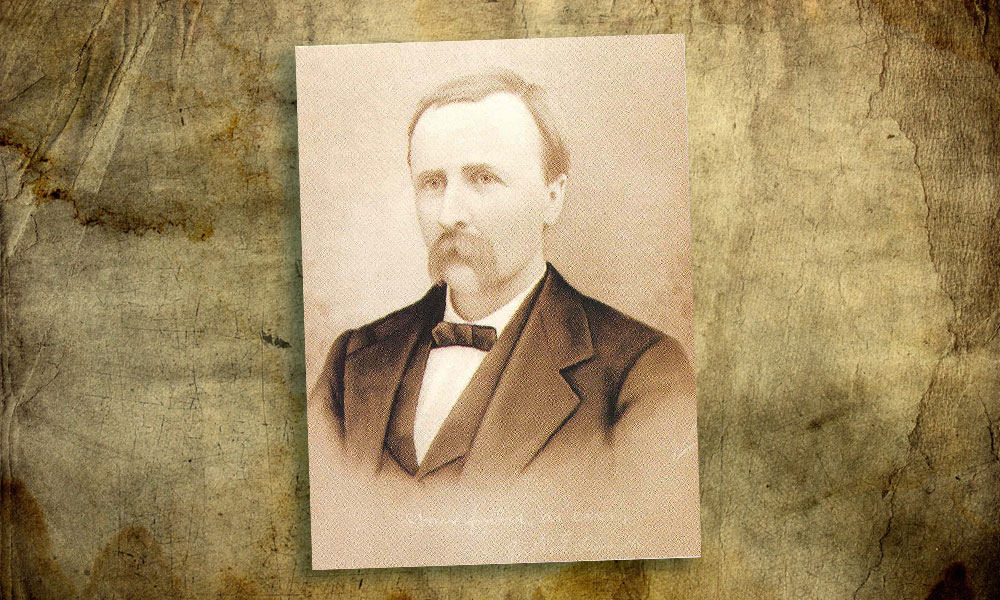

But it wasn’t until the botched Daviess County Savings Association job that Frank and Jesse were first named as suspects. In Gallatin, Missouri (check out the 1889 Squirrel Cage Jail), two men walked into the bank on December 7, 1869.

Jesse mistook bank president John W. Sheets for Samuel P. Cox, commander of the Union forces that had killed “Bloody Bill.” Being Jesse, he promptly murdered Sheets and wounded another man. Outside, while trying to escape, Jesse was thrown off his horse. His foot caught in the stirrup, and the horse dragged him 30 or 40 feet before he freed himself. Frank rode back, Jesse swung up behind his brother, and the two escaped. But they left that horse behind.

The bay mare was named Kate. She was known to be Jesse’s horse, and although Jesse said he had sold the mare to a Topeka, Kansas, man, Gallatin residents offered a $1,500 reward for the arrest of the James brothers.

From then on, until Jesse’s death and Frank’s surrender, the James boys were wanted men.

Johnny D. Boggs’s latest book, The American West on Film (ABC-CLIO), includes a chapter on the 2007 movie The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford.