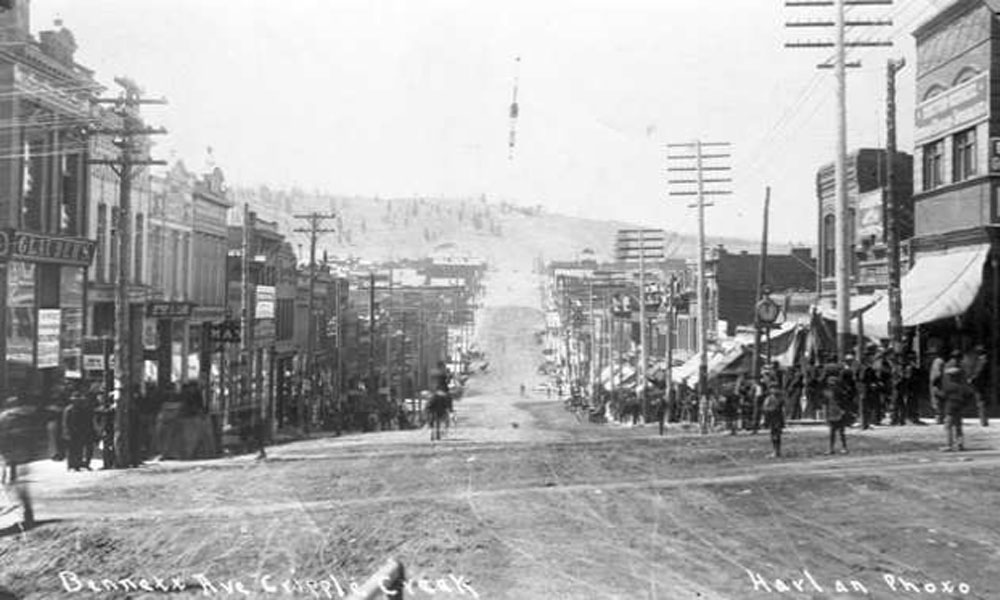

The heyday of Cripple Creek began around 1890 when a cowboy named Bob Womack found gold. For years he’d been telling anybody who’d listen the narrow cattle-crippling creek that ran through his pasture had a fortune in gold. Eventually he did find gold but things didn’t pan out well so he sold his claim for five hundred dollars. Womack missed a very rich vein by only three feet. The mine eventually paid out some five million dollars.

Over the next twenty five years prospectors panned out some 340 million dollars of the precious yellow metal. It was the richest single concentration of gold ever found in the West.

Dick Roelph struck a Vug (a cavity) of pure gold twenty-feet long, fifteen-feet wide and forty-feet high. Boulders on the floor and walls blazed with millions of gold crystals and 24 carat flakes as big as your thumbnail. Roelph quickly imported a vault door and had the

cavity sealed off. In just four weeks he took out well over a million dollars in gold.

In 1914, Julian Street, a travel writer for Colliers Magazine, journeyed to Cripple Creek, Colorado to write a feature story on one of the Wests richest gold strikes. The good citizens rolled out the red carpet for Mr. Street, taking him on a tour of the city’s churches, theaters and other cultural amenities.

Cripple Creek was typical of the mining towns with brothels ranging from elegant to rundown cribs. Among the former was the Old Homestead, which had stoves in every room, crystal chandeliers and Oriental carpets where only gentlemen of means were allowed to partake of the pleasure of a short-term love affair. It was well-known

for its pretty employees. The majority of Cripple Creek’s prostitutes occupied abodes of lesser elegance.

The most beautiful of Cripple Creek’s prostitutes was the Old Homestead’s Pearl DeVere. Whenever Pearl went out in public wearing an elegant French gown with an ostrich plume planted in her dyed red hair men sighed and women provided a cold stare and little girls swooned in envy. She threw spectacular parties and served the finest wines. It was during one of those parties that Pearl went upstairs and overdosed on morphine.

An anonymous gentleman paid for her funeral and the Elks band marched in her parade playing “Goodbye Little Girl, Good bye.”

By happenstance Julian Street ventured into Cripple Creek’s storied red light district’s Meyers Avenue. It must have made quite an impression on Mr. Street because most of his article focused on the painted ladies of “district.”

He wrote, “I walked up the main street a little ways and Meyers Avenue, the old red light street with a tumble down dance hall and a long line of box-style houses called cribs.”

He noticed the names on the door bore such names as Clara, Louise and Lina. His story also included an interview with 43-year old madam, Leola Ahrens, also known as “Leo the Lion.”

He described her crib as a tidy room with a couple of chairs, an iron bed and a cheap oak dresser. On the wall was a picture of Cupid and another she described as herself as a young girl. She also asked him to “Send some nice boys up here and have them ask for Madam Leo…… I been here for years.”

During the Cripple Creek’s heyday in the 1890s she gained fame for the day she stood drunk and naked on the corner of Fourth and Meyers Avenue shouting “I’m Leo the Lion, the queen of the row.”

When Street interviewed her in 1914 she was a subdued, middle-aged woman with “jet black hair and orchid-colored cheeks.”

When Julian Street’s story appeared in Colliers, Cripple Creek’s city fathers were livid. In retaliation, they returned the insult by renaming Meyers Avenue, “Julian Street.”

Marshall Trimble is Arizona’s official historian and vice president of the Wild West History Association. His latest book is Arizona Outlaws and Lawmen; The History Press, 2015. If you have a question, write: Ask the Marshall, P.O. Box 8008, Cave Creek, AZ 85327 or email him at marshall.trimble@scottsdalecc.edu.