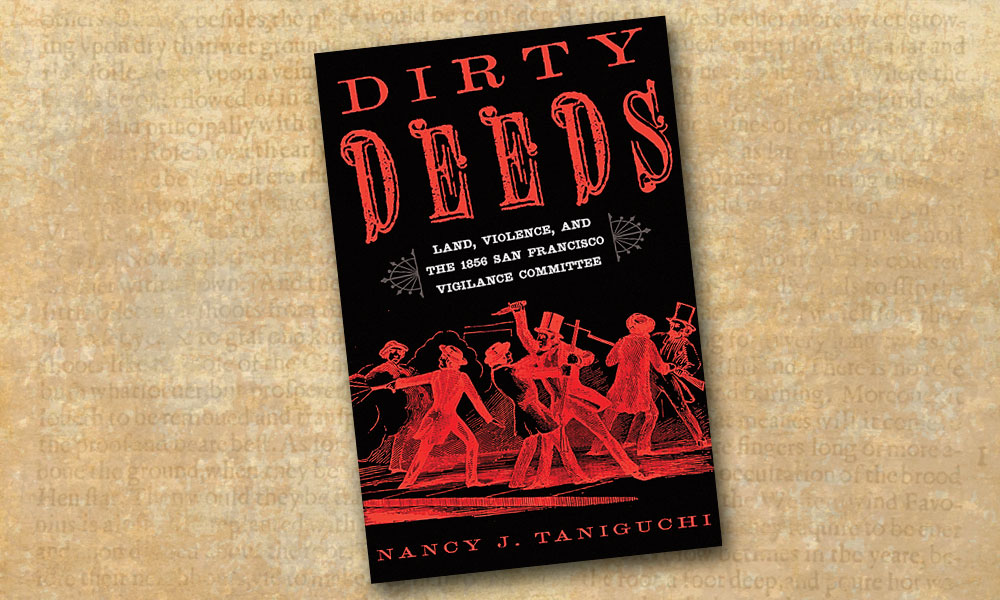

When you think of the far West before statehood, you tend to equate justice with “hemp justice,” Judge Lynch; vigilante stringing up outlaws on the nearest tree. But this was not the case when wild and wooly Nevada was born out of a single tiny community.

When you think of the far West before statehood, you tend to equate justice with “hemp justice,” Judge Lynch; vigilante stringing up outlaws on the nearest tree. But this was not the case when wild and wooly Nevada was born out of a single tiny community.

Before it became a Territory of the U.S. (and before it ended up, alas, as a sort of “mineral plantation” of San Francisco bankers), it was the westernmost section of the Mormons’ 1849 State of Deseret, and it was almost unoccupied, except for Indians.

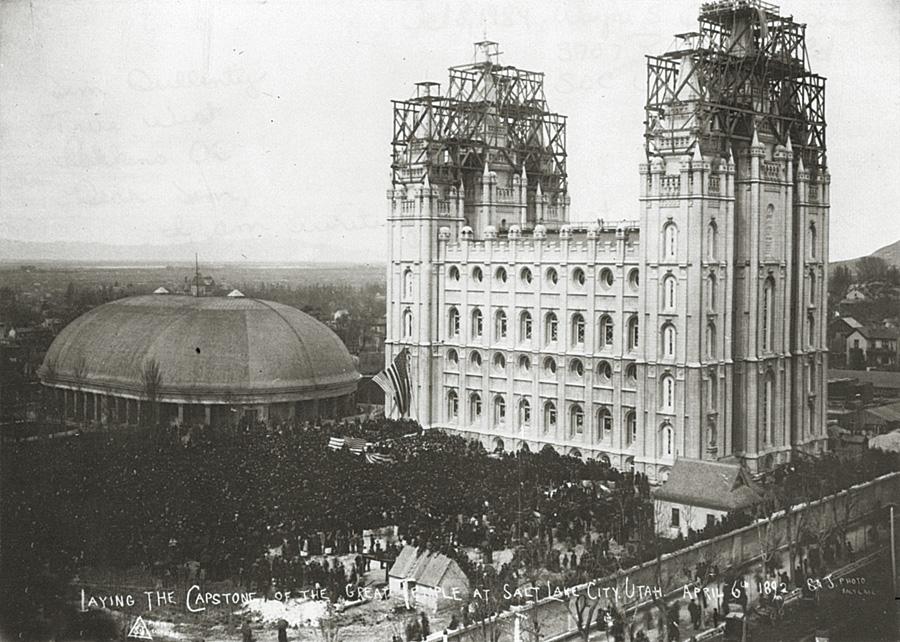

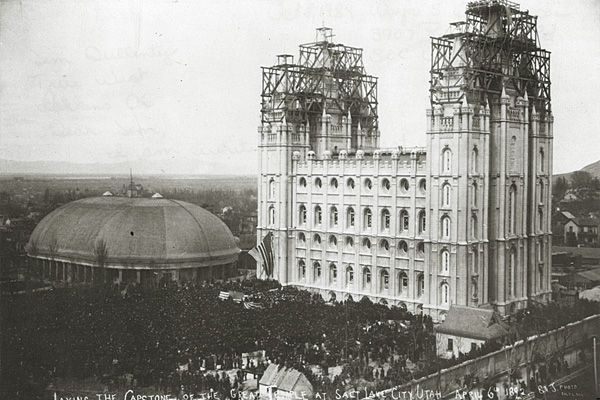

The very first settlers were only temporary sojourners who located in the Carson Valley, smack up against the Sierra Nevada. The valley was named for explorer Captain John C. Fremont’s scout, Christopher (Kit) Carson. The settlers were members of Brigham Young’s Latter Day Saint (Mormon) flock in Salt Lake City who were tempted to head for California by news of the gold discovery there. En route, some of them decided to halt and to “mine” the emigrants who were preparing to move across the Sierra via the Overland Trail’s Carson River Route.

The hardy entrepreneurs, led by a clerk named H.S. Beattie, bought bacon and flour in California and hauled it over the mountains to sell, at a substantial mark-up, to hungry emigrants. The Mormons did not even bother to build cabins, but just holed up in a makeshift fort, a little stockade of logs without floor or roof. And in the fall or winter of 1850, they packed up and left for Salt Lake City.

But word of the men’s success got around, and in the summer of 1851, Colonel John Reese, for whom the later Reese River Mining District at Austin, Nevada was named, brought 17 followers to the site with horse, mule and ox teams—mostly oxen. He later recalled that he arrived on June 1, but some accounts have him and his men not beginning to build another log fort till Independence Day. This one was a strong stockade, like one of Dan’l Boone’s Kentucky outposts, very rare in the far West. It offered complete protection from any hostile Indians.

Because they set up a supply station (or trading post) for Overland Trail travelers, the settlers called their settlement Mormon Station.?It was at the most fertile spot in the Carson Valley although, later, Chinese coolies had to be hired to dig a ditch from the Carson River to irrigate their bone-dry fields. Reese’s first order of business, after the fort was up, was the fencing of his 30-acre field. He then plowed it to be ready for the next season’s planting. In 1852 he harvested wheat and barley, corn, melons and turnips to sell. Even the lowly roots brought him $1.00 a bunch from pinch-gutted travelers on the trail.

Although there was no law in Mormon Station, there was no disorder either. The Mormons held a meeting to survey and record their individual land claims and subdivided Carson Valley in the democratic fashion of law abiding, staid Salt Lake City. They even had an ad hoc court to handle land disputes. This quasi-legal “squatters” court, of course, was ignored by everyone outside of the Valley. But the court worked well for the locales, keeping the peace.

The first appearance of justice in the legal, not the philosophical, sense occurred as early as 1853. Acting Justice of the peace E.L. Bernard tried a civil case. It was quite undramatic except for the amount of money involved. It was an attachment for the recovery of $675—no small sum in Nevada’s pre-silver rush days.

The mid-1850s saw a reverse flow of population as disappointed gold-seekers crossed eastward over the Sierra Nevada to prospect in the Great Basin. This made more business for Mormon Station’s gardeners, but these newcomers were disgruntled Gentiles, non-Mormons, and friction between the two classes of residents quickly grew.

A petition in favor of a Territory separate from Utah was sent to the Federal government, but no one in Washington paid any attention to the appeal by a handful of people on a godforsaken frontier. Next, 43 men signed a petition asking the California legislature to annex the Valley. This, too, was ignored.

By 1854-55, the Latter Day Saints were in the minority, locally. To hang onto Nevada, the legislature of huge Utah Territory (formed in 1850 and enormous, including not only Utah and Nevada, but parts of Colorado and Wyoming) attached the Carson Valley to Salt Lake City County for judicial purposes. Then the legislators organized Carson County, Utah Territory, with Mormon Station the county seat.

At about the same time, Brigham Young, not just the leader of the LDS?Church but also the governor of Utah Territory, sent additional colonists and dispatched a probate judge to the little settlement. And he was no ordinary jurist. He was Orson Hyde, one of Brigham Young’s right hand men. Indeed, he was one of the Church’s ruling Twelve Apostles.

Hyde’s orders were to organize the county, serve as probate judge, and act as temporal as well as spiritual leader of the community. He arrived in June of 1855 and arranged for local elections under territorial laws, thereby putting an end to the squatters’ democracy, although the new county did recognize the validity of the latter’s records. Hyde also re-surveyed the Valley, renamed the settlement Genoa, and founded Franktown, 25 miles away, as a sawmill town to produce lumber for the growing number of homes and farm buildings.

Judge Hyde convened the first session of his probate court on October 3, 1855. It was held in the home of a family named Cowan, for want of a courtroom. Apparently, his probate court doubled as a criminal court, too, for in that year of 1855, Nevada finally had its first criminal case brought to trial. It was an odd one, hardly the expected case of assault or robbery (much less murder) anticipated in a frontier town growing disorderly, if not violent, from an influx of newcomers. In fact, it was about as far as possible from the shoot-outs of Lincoln, New Mexico Territory, or Tombstone, Arizona Territory, as can be imagined.

The charge was: “Using language of a highly threatening character.” And the defendant was no Western hardcase, but a Negro named Thatcher. This hot-head was not only accused of threatening a man—“I have enough spite in my heart against A.J. Wycoff to kill him!”—but also of warning that, “I could cut the heart out of Mrs. Jacob Rose and roast it on the coals!”

The Judge ordered the arrest of the ex-slave. His intimidating language was proven, beyond any reasonable doubt. But, to the surprise of everyone, Justice Hyde held that the utterances were not legally threats. His Honor observed that a man could have enough malice in his heart to kill another person, but could also have sufficient judgement and discretion to prevent himself from actually committing such a deed. And, while he might feel the urge to cut out a lady’s heart and roast it, after some time he most likely would have enough good sense not to carry out the act.

So the Judge, obviously a firm believer in free speech, only fined Thatcher $50 for the cost of the lawsuit. But not entirely p.c. (politically correct), he sternly advised the accused to repair, at once, over the mountains to California and back into the custody of his former master.

Around 1855-56, about 60 to 70 more Mormon families arrived in the Valley to the great annoyance of the non-LDS men. They resented Hyde, his co-religionists, and especially his leader Brigham Young, whom they dubbed the “Mahomet” of the Mormons. After only a year or so of his reign, Hyde was recalled by Young to Salt Lake City to attend to more pressing duties as the undeclared Utah War (1857) loomed between the U.S. and Utah.

Shortly after Hyde’s recall, the Territory abolished the county government in Genoa and tried to rule the Carson Valley again, directly from Salt Lake City. James M. Crane, who became delegate-elect to Washington when Congress created Nevada Territory in 1861, recalled that armed bodies of “Christians” (he did not use the Mormon term, Gentiles) faced equally armed Saints. The latter had tried to expel the non-believers but failed, and had to settle for a truce. Crane claimed that Salt Lake City then “surreptitiously” appointed a new probate judge for a re-organized county, but that the majority of Genoans refused to obey “Mormon statutes.”

So Nevada was on the verge of rebellion against Utah, with the Gentiles particularly worried about the role of the Indians. Crane claimed that “Some of these tribes are professed Mormons, while others are under their influence.”

As the U.S. Army Dragoons prepared to invade Utah Territory, Brigham Young called on all Saints to return home. About 130 overloaded wagons began to roll out of Genoa for the long drive to Salt Lake City. The Latter Day Saints left all of their property to the Gentiles, a handful of Jack Mormons (apostates), and the Indians. Young’s reinforcements were not needed in the bloodless Utah War, which was settled by diplomacy, but few Saints returned to Genoa.

In the meantime, the first U.S. district court arrived in Genoa, in the person of Judge Joseph H. Drummond, on July 18, 1856. He set up shop in various homes and even barns, for Nevada still lacked a courthouse. Drummond’s first sessions were held in the barn of a Mr. Mott in Mottsville (now a ghost town) a few miles south of Genoa.

The Grand Jury chose to hold its deliberations not in Mott’s barn, but in his house. It had to adjourn during the blistering heat of midday to the slightly cooler Mottsville blacksmith shop. (Obviously, the smith was not stoking his forge.)

Perhaps it was Nevada’s notorious summer heat, but Judge Drummond lasted just six weeks on the bench before he decamped, high-tailing it for California, from which he never returned. Drummond’s successor, John Cradlebaugh, was made of sterner stuff. He stuck it out as U.S.?district judge for quite a spell, but had difficulty in enforcing federal law in 1860. In fact, only the support—and political prestige—of the rising lawyer Bill Stewart kept the Judge in business.

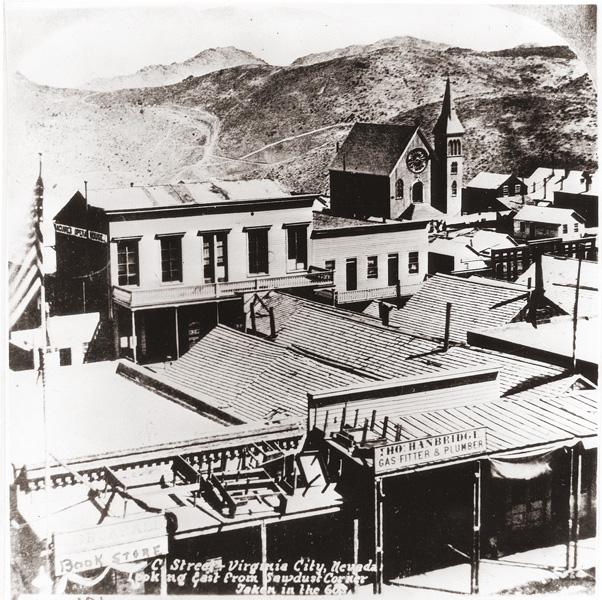

J.?Ross Browne, one of the West’s first humorists, was among the prospectors flocking to the Carson Valley from California in 1860. He found the little town of shopkeepers, teamsters and sawmill workers to be less than prosperous, although every resident he met assured Browne that he had a rich silver mine in the nearby hills. Browne saw that even Carson City was eclipsing its rival, Genoa, while Virginia City seemed destined to become a silver metropolis, a sort of “Frisco” in the sagebrush. He was right. For example, Nevada’s first paper, the Territorial Enterprise, was born in Genoa, but migrated to Carson (the future state capitol), and ended up famous because of its reporter, Mark Twain, in Virginia City.

Browne did not cotton to Washoe, as Nevada was still being called in 1860. Its few little towns, like Genoa, were now disorderly places. In fact, the whole region, thanks to the influx of Californians, seemed to be crawling with swindlers, drunks and fighters. So Browne went back to California.

Even though J. Ross Browne found Genoa “disorderly,” it was never the scene of shootings like those depicted in Shane and High Noon. Taking the criminal calendar of 1859 as a good example, one finds that the Grand Jury issued five bills of indictment for lewdness and one for adultery. There were just six cases of assault with intent to kill, and only three cases of murder.

The single “classic” case of an outlaw being tried for murder involved that major figure of Nevada’s early history, William Morris Stewart. Bill Stewart was already well known in California mining and legal circles when he crossed over the Sierra to become a Washoe lawyer. He was later elected Nevada’s first senator. He really became famous when he collided with Samuel Brown in Genoa in the summer of 1860.

Fighting Sam Brown was not content to just run a “station” (store) on the Carson River; the loud-mouthed braggart was determined to become the “Chief” of Virginia City. He boasted that he liked to “have a man for breakfast.” He affected Mexican spurs with big rowels on his boot heels, although he was no ex-California vaquero, and he strutted around town with his red side-beards tied together under his chin. His get-up would have been laughable were he not so dangerous. The lying braggart boasted of having killed 16 men in Texas and California. This claim was heavily discounted by the public, but it was known that he had killed his first victim in Texas and had killed three Chilenos and wounded a fourth in Fiddletown, in California’s Mother Lode. For these crimes, he was put away in San Quentin Prison, but only for two years.

Nevada historian Myron Angel credited the desperado with three murders in Washoe in 1859-1860. Although the sociopath had a six-shooter always riding on his hip under his coat tails, he preferred to knife men to death. When someone once asked to borrow a knife to cut some slices of bacon, Brown would not lend it, saying that he was “superstitious” about using a blade (that had taken five men’s lives) for such a purpose .

In 1859 Brown picked on Bill Bilboa, a loner in a saloon, and stabbed him repeatedly for no good reason other than his own personal entertainment. In January of 1860 he stabbed Homer Woodruff to death and it looked like the desperado planned to open his own private cemetery. His most heinous crime was his stabbing of a man named McKenzie, to death, in a saloon in 1861—and then cutting the victim’s heart out! Then the murderous brute laid down and took a nap on top of a nearby billiard table.

When a pal of Brown’s, whose name has vanished from the records, was arrested in Genoa and charged with murder in the summer of 1860, Fighting Sam decided to spring him. When Brown rode down to Genoa from Virginia City, he found that court was already in session under John S. Child, a Territorial judge, who was reorganizing Carson County with the help of Bill Stewart as prosecuting attorney.

The badman strode into court, his ostentatious spurs jingling a warning that sent jurors and spectators alike sliding under their benches or diving out the window. The panic pleased the bully, of course, but he was taken aback to see one man calmly standing in front of the Judge’s bench. It was Stewart, red-haired like the loutish Brown, but a bigger man at six-foot-two (back when few men were six-footers), and weighing over 200 pounds.

The attorney stood calmly, with aplomb, his arms folded, as the bandit came up to him with a scowl on his ugly face. Stewart was calm because he had three secret weapons. First, he knew—or at least sensed —that the badman was a coward at heart, a vil-lain who preyed on lone in-dividuals, usually peaceable and perhaps unarmed. Then, as he slowly unfolded his arms while Brown approached him, Stewart revealed his other weapons. In each hand he held a derringer.

To the surprise of the court, Sam Brown, the terror of Virginia City, suddenly became as meek as a church mouse. The lawyer escorted him to the witness stand, swore him in, and persuaded him to give testimony that helped convict his crony. Stewart then escorted Sam to the door, at derringer-point, and sent him packing.

The humiliated Browne returned to his life of crime in Virginia City, but made the error of firing a shot at an innkeeper. This proved to be a bad mistake, for the inn’s Henry Van Sickle was a man of Bill Stewart’s character. He picked up his shotgun and blew Fighting Sam to hell, thereby winning the congratulations of the citizenry of both Genoa and Virginia City, including the coroner and his duly-appointed jury.

When Congress created Nevada Territory in 1861, the first territorial legi-slature named Genoa the seat of government for Douglas County. In February of 1862, a committee informed the county’s commissioners that it had at last found a building that could be secured and “made available” for a court-house. Apparently, the concept of separation of church and state was no worry to the committee, even after the Gentile-Saint fracas. The chosen structure was the local Catholic Church—bought, leased or rented (the records are unclear on the contract) for just $75.

In 1865 Genoa got its fine brick courthouse, just in time for the town to go into a decline as Carson City and Virginia City grew. The building, near the grave of legendary Snowshoe Thompson, is a historic site/museum that is well worth a visit, along with Genoa’s reconstructed stockade-fort, all part of a Nevada State Park today.

Richard H. Dillon, is currently professor of history with the Fromm Institute at the University of San Francisco. He is a contributing editor with True West magazine

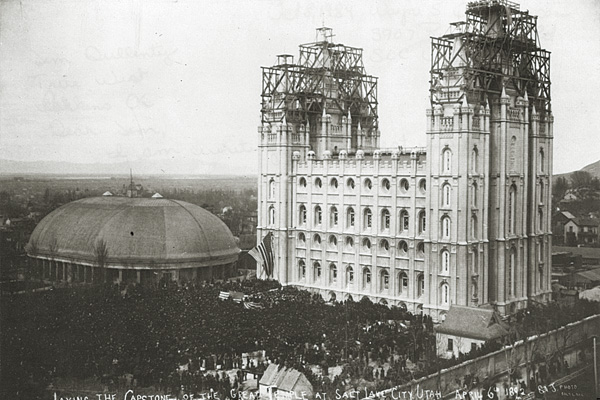

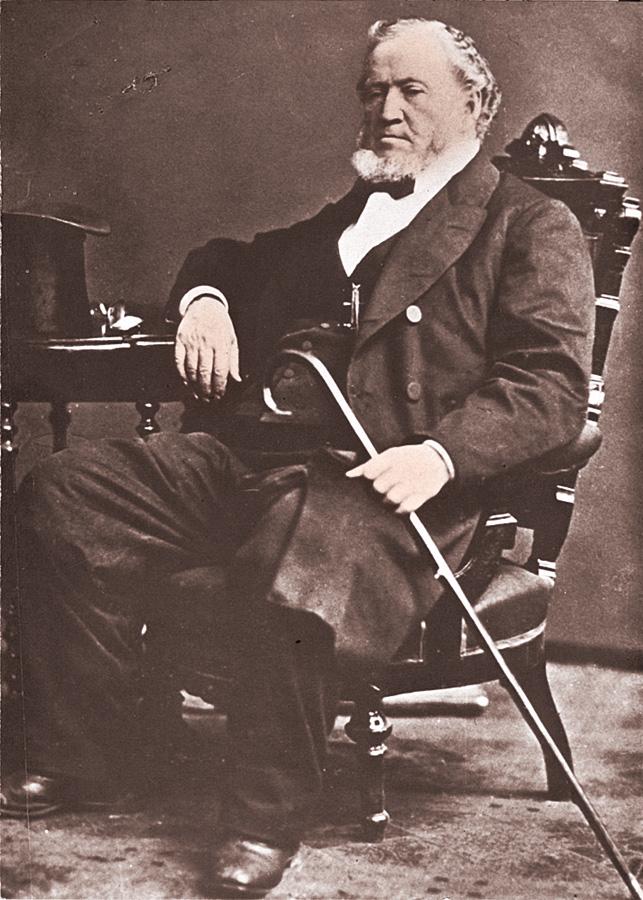

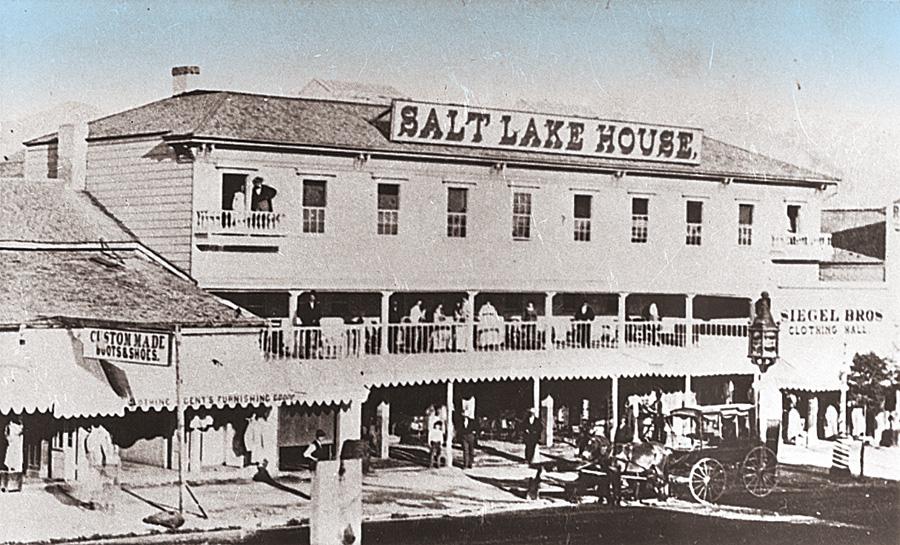

Photo Gallery

– Utah State Historical Society –

– Nevada Commission On Tourism –

– True West Archives –

– True West Archives –

– Utah State Historical Society –