Forgotten Hombre of the Lincoln County War

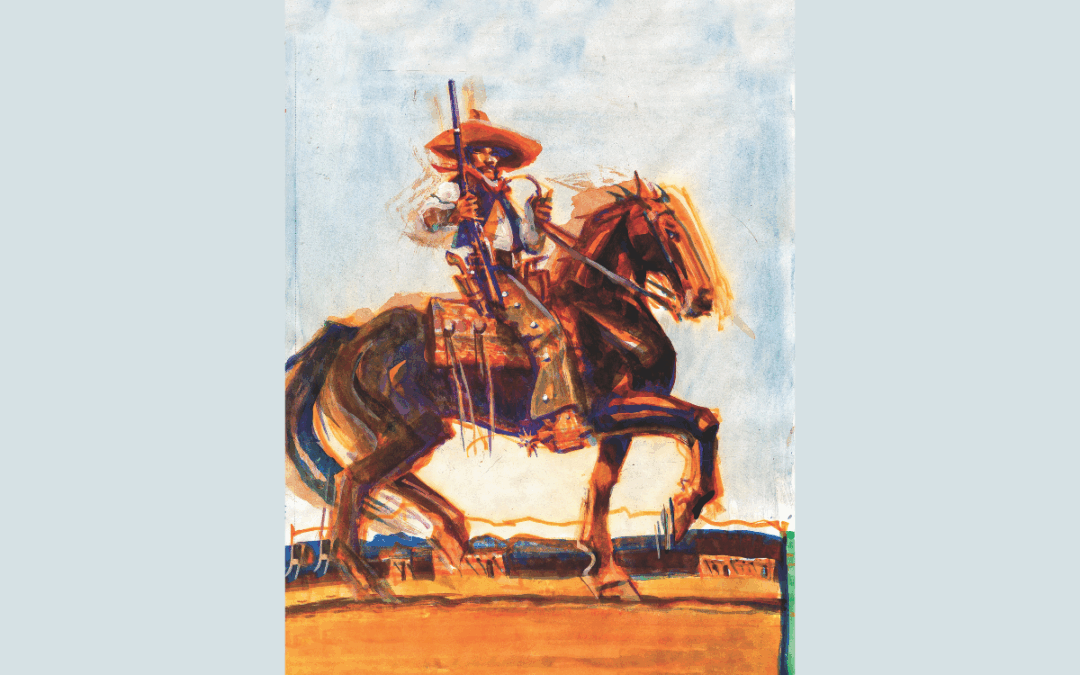

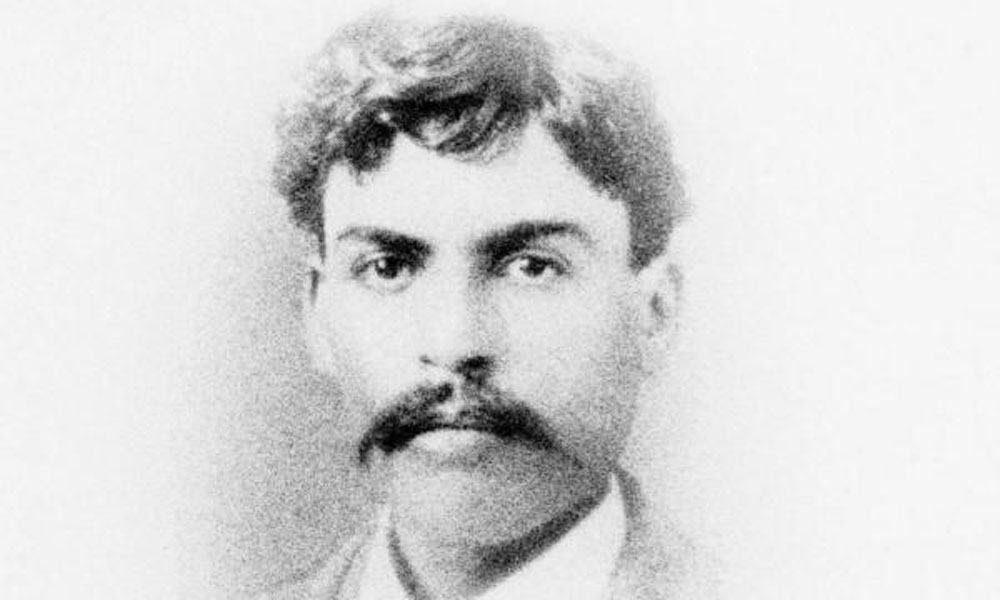

No participant of the Lincoln County War accomplished as much in his lifetime as Martín Chávez. It is therefore perplexing as to how the leader of the McSween partisans during the five-day siege in Lincoln, also known as “The Big Killing,” became the most forgotten participant of the famous conflict. One can only scratch their head further when considering Martín was not only one of the closest friends of the legendary William “Billy the Kid” Bonney,

but his own name was once known to everyone throughout the entire state of New Mexico. That former governor James Hinkle served as a pallbearer during Martín’s funeral was an accomplishment for an orphan who rose from the humblest of origins to become one of Lincoln County’s greatest Hispano success stories.

José Martín Chávez was born in the small settlement of Manzano in the eastern foothills of the formidable Manzano Mountains in Valencia County, New Mexico Territory, on December 11, 1852. He was baptized in the Our Lady of the Immaculate Conception Roman Catholic Church in Tome 18 days later. Martín had barely learned to walk and talk before becoming a huérfano (orphan) when his parents Juan and María Lauriana Chávez suddenly died from unknown causes. He would spend the remainder of his childhood living with relatives, including his uncle José Chávez and his grandmother Magdalena in Manzano.

In contrast with many Nuevomexicanos of his time, Martín Chávez received a strong education when a Catholic priest named José Sambrano Tafoya began tutoring the boy in the 1850s. Martín embraced Padre Tafoya as a mentor and father-figure while learning how to read and write, and presumably accompanying the priest on his excursions to a small chapel in a placita (village) eventually known as Lincoln on the Río Bonito in southeastern New Mexico. The growing boy would remain devoted to his Roman Catholic faith for the rest of his days, also possessing an innate sense of conservatism and a strong work ethic.

Like many residents of Manzano, 18-year-old Martín Chávez had migrated into southeastern New Mexico Territory by 1870. He established a modest farm for himself and his elderly grandmother Magdalena on the outskirts of a village called Picacho on the Río Hondo in Lincoln County. The huérfano was determined to succeed and quickly became one of the more accomplished sheep farmers in the region. Martín’s education set him apart from many of his fellow Hispanos on the Río Hondo, and he soon became the majordomo (leading citizen) of Picacho. If there was a problem or concern in the community, the local farmers and sheepherders all looked to him for leadership or advice. It was a status Martín retained for the next five decades.

The citizens of Picacho were looking to Martín Chávez for reassurance and guidance during the Horrell War in January 1874. The violent race war between the Horrell brothers and the Hispanos of Lincoln County encroached on Martín’s home turf when Horrell associates Ben Turner and Edward Hart rode into Picacho that month. The dangerous duo were leaving the village after failing to acquire some corn when Turner was fatally shot by a bullet fired through a porthole of an adobe wall. Many people believed Martín Chávez was the hombre who left a puff of smoke rising above the adobe wall that day. “It was always said that it was Martín Chávez who did this killing,” Lincoln County resident Lily Casey recalled. “But it was never known positively that this was the case.” If Martín was responsible for killing Ben Turner, his willingness to shoot down one of the Horrell brothers’ associates would have only further endeared him to the local Hispano populace.

As the majordomo of Picacho, Martín Chávez was familiar with all the local citizens, including Civil War veteran Vicente Romero and his family, who had also migrated from Manzano years earlier. Vicente and his wife, María, served as witnesses when the 24-year-old Martín married their 16-year-old niece Juanita “Juana” Romero in the Our Lady of Sorrows Church in Manzano on August 16, 1875. The wedding was fittingly performed by Martín’s mentor Padre José Sambrano Tafoya, who eventually relocated to Lincoln County himself.

In addition to farming and raising sheep on the Río Hondo, Martín became a lawman when his fellow Democrat and Lincoln County Sheriff Saturnino Baca deputized him in 1876. There was little Deputy Sheriff Martín Chávez or anyone else could do to temper the growing animosity between Irish businessmen Lawrence Murphy, James J. Dolan and John H. Riley—known collectively as “The House”—and a Scottish attorney named Alexander McSween and English merchant John Tunstall in Lincoln County.

Martín Chávez’s term as a deputy sheriff had concluded by the time John Tunstall’s murder ignited what became known as the Lincoln County War on February 18, 1878. Martín remained focused on his farming duties the next few months while a conglomerate of Tunstall associates known as the Regulators carried out a series of revenge killings against the Dolan faction members responsible for the Englishman’s murder. Although Martín initially refrained from participating in the guerrilla warfare, the sheep farmer established a strong friendship with a young member of the Regulators named Henry McCarty, alias William H. Bonney, whom many referred to as “The Kid.”

As the war between Jimmy Dolan and Alexander McSween’s factions continued raging throughout Lincoln County, Martín’s sympathies for the McSween side only strengthened after Dolan and his supporters ransacked the Hispano village of San Patricio on July 3, 1878. “The [Dolan] crowd was becoming overbearing, intolerable and very dangerous,” Martín later said. “They helped themselves to whatever they wanted—anywhere. If any one of them found a woman or a girl unprotected or alone, she was treated with insult and horrible usage. Their conduct caused them to be intensely hated.”

Alexander McSween and the Regulators were aware of Martín’s disdain for the Dolan faction when they arrived in Picacho on the evening of July 14, 1878. They wanted the widely respected 25-year-old farmer to lead them into battle upstream in Lincoln. “We knew him to be one of our sympathizers,” recalled Regulator George Coe. “We requested him to take on the leadership of our band, and promised to abide by his decisions and follow his plans.” Martín readily accepted the McSween faction’s offer, and recruited roughly 20 local Hispanos to join their ranks, including his uncle-in-law Vicente Romero.

Martín hugged his concerned wife, Juanita, and led a force of approximately 60 armed partisans up the Río Bonito into Lincoln under cover of darkness. His plan was to “gain a toehold before any resistance could be offered,” as George Coe later described it. Martín and his men managed to remain undetected by any of the locals. “Chávez placed us in various sections of town,” recalled Coe. Martín and roughly 20 of his Hispano fighters took position inside the Montaño store. Alexander McSween, Billy Bonney and others took position in the McSween home, while other members of their faction took cover in the Patrón store and the Ellis house. Jimmy Dolan and his faithful crony Sheriff George Peppin were at the western end of Lincoln in the Wortley Hotel and unaware of the McSween faction’s arrival until the following morning. Martín’s strategy had proven a masterstroke.

Martín Chávez and his armed partisans held the advantage in Lincoln throughout the next four days while frequently exchanging shots with members of the Dolan faction. They were better positioned and intending to fight it out to the last bullet. Martín was very nearly shot when briefly exiting the Montaño store to confront House partisan Lucio Montoya on the morning of July 17. “[Montoya] miraculously missed me,” he remembered. Martín and two of his hombres chased Montoya into the Romero home up the street, but were unable to find him. The Dolan loyalist had hidden inside a box in the living room and was able to sneak back to the western end of town while disguised in women’s clothing. “Years later when we were at peace, I had many hearty laughs with Lucio,” Martín later recalled.

The advantage held by Martín’s forces evaporated when Colonel Nathan Dudley and some buffalo soldiers arrived in Lincoln with a howitzer on the morning of July 19. When Dudley assisted the Dolan faction by positioning the cannon directly in front of the Montaño store, Martín stepped outside to confront the white-haired officer.

“Colonel, you want to kill me and my men in the house?” Martín asked.

“If a single shot is fired by your men, I will blow your house to pieces,” Dudley responded.

Martín ordered his men to shoot the soldier operating the howitzer if it looked like the fuse was about to be lit, but he knew the game was over. Martín sent a note to Alexander McSween suggesting they vacate the Scotsman’s home, as it appeared the army might blow them all to pieces. He then swallowed his pride and led his Hispano fighters out the back of the Montaño store and down the street to the Ellis house. When Dudley repositioned the howitzer in front of the Ellis building, Martín and his men mounted their horses and exchanged fire with the Dolan partisans while withdrawing into the northern hills across the Río Bonito.

Martín and his hombres continued firing shots at the Dolan partisans from the hills while their enemies set fire to the McSween home. After nightfall, Martín and a handful of his men tried to assist Billy “The Kid” Bonney and their comrades in the McSween house by stealthily crossing the river and aiming their rifles at the Dolan store. It was little use, as the Irishman and his supporters had surrounded the McSween home down the street. Martín approached the rear of the burning building and shouted for his comrades to come out before returning to the northern hills. “It was impossible for us to be of any assistance,” Martín lamented years later. “But we remained in the vicinity to be on hand in case they did escape.”

While Billy Bonney and some of his companions managed to escape the burning house in a hail of gunfire later that night, Alexander McSween and Vicente Romero were among those killed by the Dolan faction. “I shall never forget the night they took forcible possession of Lincoln and set fire to the McSween home,” Martín said decades later.

Feeling that any further fighting was pointless in the wake of Alexander McSween’s death, Martín informed Billy Bonney of his intention to return to his wife in Picacho at the Agua Sol ranch in the foothills of the Capitan Mountains. “As spokesman for our group, I told the Kid our decision,” he recalled. “And we parted as good friends.” While Bonney and some of their partisans were determined to continue to fight, Martín returned home and watched his uncle-in-law Vicente Romero’s funeral with a heavy heart in Picacho. “Thus ended my participation in the Lincoln County War,” he later remarked.

The Loss of a Friend

Martín resumed his farming duties in Picacho and continued transporting shipments of quality wool to Las Vegas after the five-day siege in Lincoln. The locals all turned to him and his friend August Kline for leadership while John Selman and his “Rustlers” murdered, pillaged and raped throughout Lincoln County during the fall of 1878. When Governor Lew Wallace finally arrived in Lincoln the following spring, Martín signed up as a member of Juan Patron’s “Mounted Rifles.” He later collected $6 for his service with the county militia. Martín also testified for the prosecution during a court of inquiry held in Fort Stanton for Col. Nathan Dudley regarding his conduct during the five-day-siege that summer, although Dudley was ruled innocent of charges subject to a court marshal.

On the Río Hondo, Martín and Juanita often received visits from their helpful friend Billy “The Kid” Bonney, who had failed to receive his promised pardon from Governor Wallace. Like most of the Hispanos throughout the county, Martín had embraced Bonney as the social bandit of New Mexico. “Billy was one of the kindest and best boys I ever knew, and far superior in many respects to his pursuers,” Martín recalled. “All the wrongs have been charged to Billy, yet we who really knew him know that he was good and had fine qualities.” On one occasion, the Kid helped Martín collect an unpaid wager by fearlessly shooting three cows belonging to a group of Texans and instructing his friend to collect his beef. “Kid stayed with me many nights,” Chávez remembered.

Martín tried to visit Billy Bonney in the Lincoln County Courthouse prior to the outlaw’s spectacular jailbreak in April 1881, but the malicious Deputy Bob Olinger refused. “He declared that I had been too friendly with [Bonney],” Chávez recalled. Billy paid Martín and Juanita Chávez one last visit in Picacho following his famous escape before returning to Fort Sumner. Martín advised his amigo to ride for Old Mexico or “any place a long way from here.” Billy refused to leave the territory without his intended bride, Paulita Maxwell.

“No,” Bonney insisted. “I go with my wife. If I die, I am satisfied, for I die for her.”

Martín was saddened when he learned of Billy the Kid’s death at the end of Pat Garrett’s revolver in Fort Sumner during the night of July 14, 1881. He would publicly defend his slain friend’s character and legacy for the rest of his days.

Business and Politics

1884 proved an eventful year for Martín and Juanita Chávez. Having already adopted a boy named David Billescas, the couple realized in the spring that Juanita was pregnant with their first biological child. Two months later, in late June, Martín was devastated when his mentor Padre José Sambrano died of a fractured skull after falling from his buggy on a hillside above Lincoln. Already one of the most successful sheep farmers in the region, Martín was appointed as a road supervisor shortly before his son, José “Modesto” Chávez, was born in Picacho on November 29.

With a growing family, Martín began his steady ascension in politics. He represented his precinct as a member of the Democratic County Central Committee at the Democratic Convention held in Lincoln shortly after the birth of his daughter Josefa “Josefita” Chávez in Picacho on March 20, 1887. Martín also attended the Democratic Convention held in Lincoln on August 14, 1890. He was among the delegates elected to represent their county at the upcoming Democratic Convention over in Roswell, Chaves County. Three years later, in June 1893, Martín and Juanita welcomed the birth of another son named Benjamin Chávez. In one of history’s wonderful ironies, Benjamin eventually married Emma Peppin, the daughter of his father’s one-time adversary George W. Peppin.

Having rapidly become one of the leading Democrats in Lincoln County, Martín was elected to represent his party at the territorial convention during the summer of 1894. Although he was unsuccessful in his bid for probate judge, the increasingly wealthy sheep farmer represented the local Democrats at the territorial convention in Las Vegas in June 1896. The majordomo of Picacho achieved his first significant political success five months later when elected to the Board of Lincoln County Commissioners that November.

Martín’s duties as a public servant continued in a variety of ways throughout the early 20th century. He was appointed the local postmaster in May 1900, and succeeded his brother-in-law and close friend George Kimbrell as the local justice of the peace. That job almost cost Martín his life when he was severely beaten by a gun-waving troublemaker in Picacho in January 1901. “Chávez is in critical condition and will probably die,” a Las Vegas newspaper declared. Martín recovered from his injuries and welcomed the birth of a second daughter, Marietta “María” Chávez, on November 3, 1902. The following year, he was appointed as the deputy sheriff of Picacho by the recently elected Sheriff John W. Owen.

Martín continued prospering on his “Sunset Ranch” in Picacho throughout the next decade. He cultivated profitable fruit orchards on the Río Hondo, and shipped thousands of pounds of wool to the Aurora Scouring Mills in Illinois. He also opened a successful grocery store in Picacho called Martín Chavez & Sons. The Lincoln County War veteran was making enough money to hire two live-in servants for his family, and his reputation grew to the point that even his farming activities and mere presence in a town were reported by various newspapers. He was also handpicked as a delegate by Governor George Curry to represent Lincoln County at the National Farmers’ Congress in Oklahoma City on October 17, 1907.

Age did now slow Martín as he continued selling shipments of wool in Roswell and was appointed to the Democratic State Central Committee at a convention in Santa Fe on October 3, 1911. The following autumn, Martín was nominated as a representative for Lincoln County on the executive committee for the New Mexico Wool Growers’ Association. The successful businessman was also chosen as a member of the board of control for the Eastern New Mexico Good Roads Association the following year. A man of multiple talents, Martín was appointed to the Lincoln County Board of Education in 1917, and joined the Lincoln County Council of Defense the following year while still serving on the Democratic State Central Committee.

Lincoln County became too small for Martín’s prospects, so the widely respected entrepreneur and his family relocated to Santa Fe by the spring of 1919. He established a profitable mercantile store called Martin Chavez & Sons—later renamed The New York Store—on San Francisco Street in the state capital. The 66-year-old merchant decided his days in the wool trade were over that autumn and sold all of his sheep to Jaffa, Prager & Co. in Roswell for approximately $50,000. The hard-working orphan from Manzano was now one of the most esteemed businessmen in all of New Mexico.

So Valuable a Citizen

Martín Chávez quickly established himself as a pillar of his community in Santa Fe. The businessman invested in local real estate, became a member of the St. Francis Cathedral and church societies of Saint Joseph and Saint Francis, and achieved the pinnacle of his success when Governor James Hinkle nominated him for the New Mexico State Tax Commission on March 9, 1923. Martín’s appointment was confirmed by the senate, and he was among the 34 delegates chosen by Governor Hinkle to represent their state at the four-day National Taxation Conference commencing in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, on September 24. The following year, Martín travelled east again as one of the 80 delegates chosen by Governor Hinkle to attend the seven-day National Taxation Conference that commenced in St. Louis, Missouri, on September 13, 1924.

Martín had barely returned from

St. Louis when tragedy struck his family on October 15, 1924. That was the day Martín’s son-in-law Francisco Santana committed suicide by shooting himself through the heart inside the restroom of their New York Store on San Francisco Street. The patriarch of the family oversaw the funeral procession held in Santa Fe two days later and tried to comfort his suddenly widowed daughter Josefita and his grandchildren. Martín subsequently sold his mercantile store to fellow Santa Fe merchant John Rousseau Martin in January 1925.

What was supposed to be a six-year term for Martín on the State Tax Commission began unravelling when Governor Arthur T. Hannett suddenly requested his and George Ulrick’s resignations in February 1925. Governor Hannett accused the 72-year-old Martín of negligence due to his advanced years, and removed him from the tax commission that spring. Martín’s and George Ulrick’s attorneys tried to fight against their dismissals in what became known as the “State Tax War,” but Governor Hannett eventually emerged victorious. Martín subsequently retired after decades of public service and enjoyed the fruits of his many labors with his family.

Martín never forgot his amigo William Bonney and was given the chance to reminisce about the old days when interviewed by Walter Noble Burns while the author worked on a book about the famous desperado titled The Saga of Billy the Kid. Martín was unimpressed with Burns and various other authors’ depictions of his late friend, as he informed former governor Miguel Antonio Otero Jr. in Santa Fe during the summer of 1926. Otero was planning to write his own book about the Hispano population’s favorite bandido and devoted an entire chapter to Don Martín’s recollections. “We have not put our impressions of [Billy] into print and our silence has been the cause of great injustice to the Kid,” Martín insisted.

Martín and Juanita moved into a new home at 518 College Street in Santa Fe in 1927. The elderly couple were enjoying their autumn years when tragedy struck their family again during the spring of 1930. Their daughter Josefita’s 21-year-old son Henry Santana was killed in an automobile accident outside of Watrous, Mora County, on April 10. Martín served as a pallbearer during his grandson’s funeral service held inside the St. Francis Cathedral two days later.

José Martín Chávez’s own funeral service would be held in the same cathedral after the 78-year-old journeyman died of pneumonia in his home at 2:30 in the afternoon of December 8, 1931. His passing was reported in several newspapers—in as far as Wyoming—including the Santa Fe New Mexican, which published both an obituary and a partly accurate account of his remarkable life:

Don Martin belonged to the McSween section, the crowd of which Billy the Kid was the hero. Interviewed in recent years by authors of Billy the Kid books, Don Martin stoutly resented word pictures that made the Kid appear in the role of a “crook.” He was loyal to his friends, he said, not a killer for the sake of killing… Martin was born at Manzano, but “drifting down” to Picacho he became a rancher in Lincoln County in the days when history was being made with six-shooters…

Martín’s funeral service was held in the St. Francis Cathedral on December 11, 1931. “There were many beautiful floral designs, each bearing a message of deep sympathy in the loss to the community of so valuable a citizen as Mr. Chaves [sic] was,” the New Mexican announced. Former governor James F. Hinkle, George Ulrick and “Colonel” George Prichard acted as pallbearers, and Martín was buried in the family plot in the Rosario Cemetery on North Guadalupe Street. His devoted wife Juanita Romero-Chávez was buried with him following her passing on April 21, 1947.

For all of Martín Chávez’s achievements and decades of success—and his recollections of New Mexico’s most famous conflict being published in Miguel Antonio Otero’s The Real Billy the Kid: With New Light on the Lincoln County War in 1936—the majordomo of Picacho was largely forgotten in the decades following his death. His name has only been mentioned sparingly by most historians, and he has never been portrayed on screen in any of the dozens of films about his famous amigo Billy Bonney.

An hombre who survived the Lincoln County War and exceeded the more famous Juan Patrón as a businessman deserved better.