He was born in the heat of a long Southern summer, on the fourteenth of August 1851, in the up-and-coming city of Griffin, Georgia. The only son of the oldest son, primary heir of the Holliday family and future guardian of the family’s good name, John Henry Holliday shouldered a heavy burden for which he was well groomed. From his father, Henry Burroughs Holliday, he learned the cool courage of a military man.

He was born in the heat of a long Southern summer, on the fourteenth of August 1851, in the up-and-coming city of Griffin, Georgia. The only son of the oldest son, primary heir of the Holliday family and future guardian of the family’s good name, John Henry Holliday shouldered a heavy burden for which he was well groomed. From his father, Henry Burroughs Holliday, he learned the cool courage of a military man.

From his mother, Alice Jane McKey Holliday, he learned the genteel ways of plantation society. From his family he learned that loyalty was the sign of a Southern gentleman. And whatever else he would one day become, John Henry would always be a gentleman.

Another baby born to his parents only a year-and-a-half earlier, christened Martha Eleanora, had died at only six months old. And though his parents no doubt dreamed of other babies to fill their home, John Henry would be their only living child.

This, however, didn’t mean the Holliday house was empty of family—Henry Holliday had come to his marriage with one son already, a Mexican orphan boy he had found during his service in the war with Mexico and had taken home as a foster child. Francisco Hidalgo (aka E’Dalgo) was near 15 years old when John Henry was born, but still living in Henry’s home, a kind of adopted older brother to Henry’s new son. Alice Jane had family with her as well, two younger sisters and a younger brother who had come under Henry’s guardianship when their own father passed away. So with those seven family members and the usual servants, the Holliday’s home on Tinsley Street was far from empty.

The War Between the States changed all that. Henry Holliday enlisted in the Twenty-seventh Georgia and was made a major in the Quartermaster Corps at Manassas and Richmond. Francisco Hidalgo, who had adopted the birthday of July 4 in honor of his new country, showed his patriotism by joining Company A of the Thirtieth Georgia Infantry. Alice Jane’s brothers, James Taylor, William Harrison, and Thomas Sylvester McKey went to war as well, and all at once the Holliday house was empty of men with only the women and young John Henry still at home.

Though the little family was far from the fighting for most of the war, they still felt its impact. With Griffin’s central location on the Macon and Western Railroad, their hometown soon became a training ground for most of the troops leaving out of Georgia.

In the midst of the struggle, Henry Holliday came home on a medical discharge, suffering from a bout of “watery dysentery” that had cost him his commission and ended his proud military career. The Major returned home to Griffin just in time to bury his own father, Bob Holliday, who passed away in November of 1862 and was laid to rest in nearby Fayetteville. John Henry surely attended his grandfather’s funeral. For the 11-year-old boy, it was only the first of many.

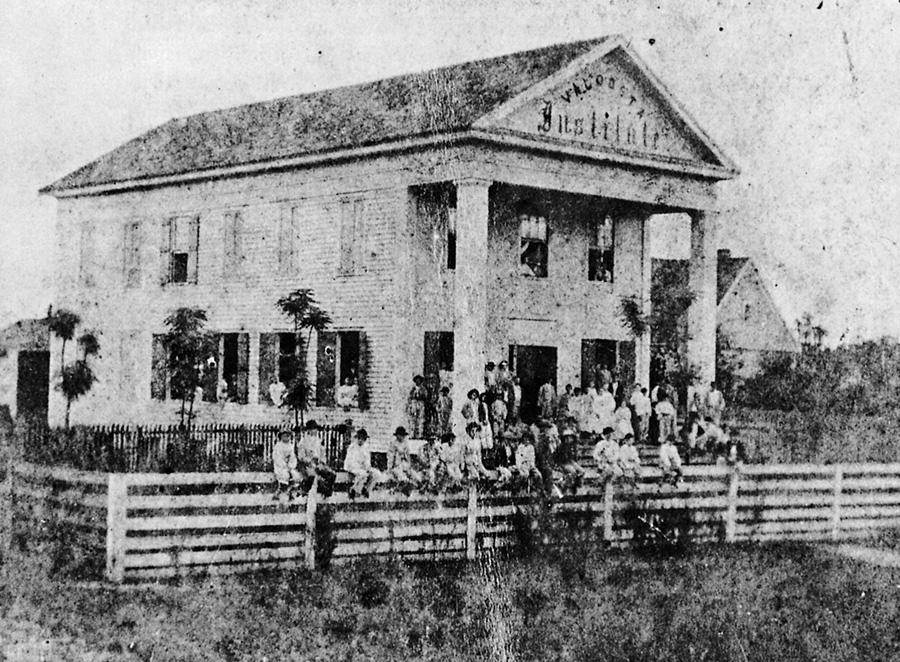

The next came soon after the war ended, in the south Georgia village of Valdosta where the Hollidays lived as refugees from the Yankee invasion. For most of the war years Alice Jane McKey Holliday had been ill, and the lingering sickness finally took her life in the fall of 1866.

John Henry was barely 15 years old when his mother passed, but he was well aware of the Southern traditions of mourning: After the burial, a child mourned a parent for one year, spending the first nine months wearing black and the last three months wearing gray, abstaining from unnecessary social activity. A husband mourned a wife for one year as well—breaking this tradition was considered gross disrespect for the dearly departed. So it was with shock and hushed surmise that the folks of Valdosta witnessed the marriage of Major Henry Holliday, widowed just three short months, to Miss Rachel Martin. The fact that she was half the major’s age and a near neighbor during the late Mrs. Holliday’s long illness, only added to the speculation.

In a surprisingly unfamilial move, a lawsuit was brought by Tom McKey to recover his sister’s inheritance. He petitioned the Lowndes County Superior Court for a return of his deceased sister’s property, which would otherwise have gone by law to her widowed husband. The property was substantial. Alice Jane had been the daughter of a wealthy plantation owner when Henry Holliday had come calling. Their courtship was a coup for Henry, whose own father was a small-time farmer and tavern keeper in nearby Fayetteville. But Alice Jane’s father, William Land McKey, was gentry who had married into one of the wealthiest families in north Georgia. The Aaron Cloud clan owned property from Stone Mountain to Griffin.

The most impressive property of the inheritance was a fine two-story brick structure in the heart of Griffin’s busy commercial district. That building, called the Iron Front, faced Solomon Street with fancy iron cornice work and tall arched windows. The Iron Front was a real moneymaker. It was also the most disputed property in the legal wrangling between Tom McKey and his brother-in-law Henry Holliday.

The original record of the trial lost, a copy of the judge’s decree remains in the Spalding County Courthouse deed book in Griffin, Georgia. It details the unique solution to the case. With the wisdom of Solomon, the judge divided the Solomon Street building in half to be shared by both families. The Iron Front was to be divided by a partition wall running down the center, the west side of the property for the McKeys and the east side for Henry Holliday as guardian of his son’s inheritance. The irony of the solution could not have been lost on anyone who heard of it.

And what did young John Henry think of his family’s legal dealings, dividing McKey and Holliday—being a bit of both himself? Local folks remembered a good boy who seemed a little confused and got himself in with the wrong crowd.

He was 16 years old when the legal battle ended, a troubled teenager in the troubled times of Reconstruction. Georgia was under martial law while the United States government forced its new Constit-utional Amend-ments on the unwilling citizenry, and Valdosta was overrun with federal troops. In the midst of that heated atmosphere, the arrival of Mr. J.W. Clift, running for United States congress on the Republican ticket and promising 40 acres and a mule for every colored man who supported him, only added to the explosive conditions. It was hardly a surprise when a keg of gunpowder was discovered under the courthouse steps just as Mr. Clift was about to make his political speech. But the keg went unused while the Yankees ferreted out the attempted bombers and took them off to Savannah for a military trial. Their names read like a Who’s Who of the best families in Valdosta, and some say young John Henry Holliday’s name would have been listed there too, if his father hadn’t sent him out of town before the Yankees got ahold of him.

It wouldn’t have been a difficult thing for Henry Holliday to spirit his son out of town to keep him from standing trial for treason, and hanging for it if he were found guilty. Henry had worked for a time as local agent for the Freedman’s Bureau, and had earned the respect of Yankees and Rebels both. So if John Henry were involved in that bombing plot, he was lucky to have a father with political connections—and family living in far-away north Georgia.

Jonesboro was a safe refuge while the military decided what to do with the plotters. Henry had a brother living there, Robert Kennedy Holliday, who worked as a baggage master at the Western and Atlantic Railroad depot and owed Henry a debt of hospitality. During the war while Rob had been off serving as quartermaster captain with the Seventh Georgia Regiment, Henry had given shelter to his brother’s family when their home was threatened in the fierce fighting of the Battle of Jonesboro. Having Henry’s son in Jonesboro for a summer would be small recompense for that kindness, and according to family records, that’s where John Henry spent one teenage summer.

It was an interesting season, as some tell it. John Henry made himself useful around his Uncle Rob’s home place and found himself in a teenage romance with his uncle’s oldest daughter, Mattie Holliday. Though Mattie was 18 months older than John Henry, they had always been close, and if she hadn’t been a Catholic, the family might have agreed to a courtship between the cousins. Close relations often married in those times, and previous generations of Hollidays had included cousins who married—even an uncle who married his own niece. But Mattie’s Catholic faith forbade such unions in any degree nearer than second cousins, so a public romance between the two was impossible.

But impossible romances are oftentimes the most alluring, and some believe that John Henry and Mattie continued their fond feelings for one another into adulthood, though the truth seems to vary with the source. The McKeys said they were sweethearts. Mattie’s relatives said they had hoped to marry. The rest of the Hollidays said they were nothing more than dear friends. The one known fact is that John Henry and Mattie corresponded throughout their lives, and that she kept his letters and photographs close to her.

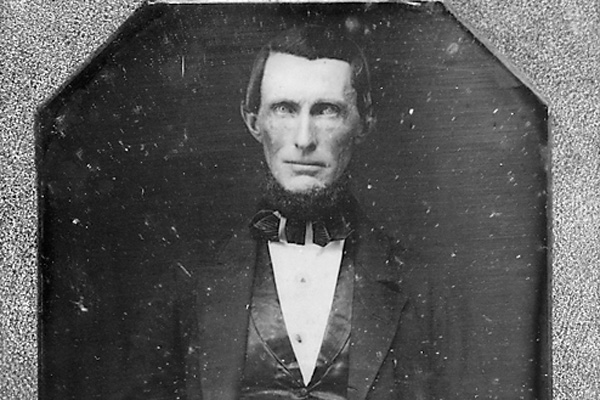

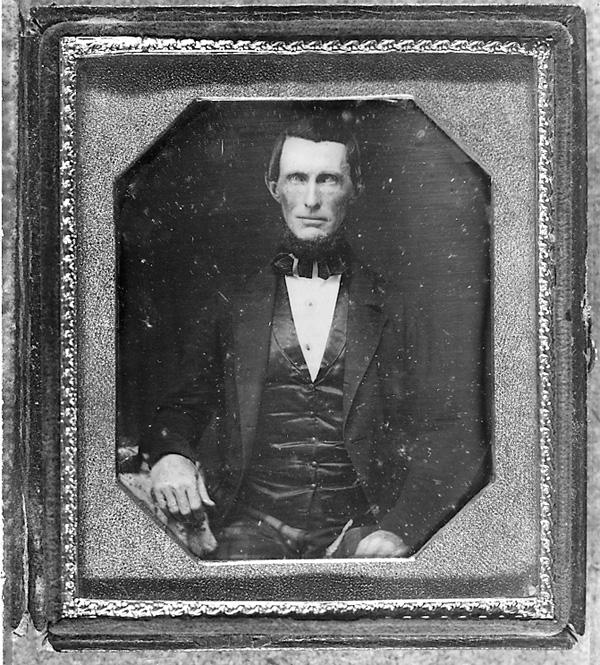

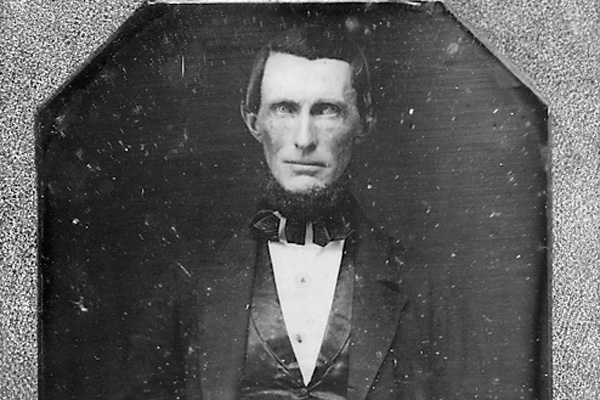

One of those photographs came from Philadelphia where John Henry went to study dentistry. It is a proud young face, and he had reason to be proud of himself. Attending the Pennsylvania School of Dentistry was an honor and reflected the excellent work he had done in school, in spite of the troubles of his teenage years. It was also an expensive way to gain an education in an era when most dentists were still trained by older practitioners in small towns. But Georgia was a progressive state and required newly licensed dentists to show completion of a dental education program—the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery was one of a handful of such institutions in the country.

To help pay for the cost of his professional education, $100 dollars per year plus the expense of books, John Henry took a summer job working for the Atlantic and Gulf Line Railroad out of Valdosta. Though his family was doing well enough—between Henry’s income from selling furniture out of Ziegler’s Hall in Valdosta and the profits he made from his muscadine grape orchards and pecan groves—still, they weren’t wealthy people, and John Henry’s professional education was a pricey privilege.

It was a rigorous course of instruction that John Henry began that fall of 1870. In addition to the regular coursework, he spent four hours a day in the dental clinic, treating patients under the watchful eye of faculty demonstrators. In two years of study and clinical work, he knew all the latest techniques in dentistry as well as more medicine than many country doctors.

But graduation from the dental school required more than just coursework—the Pennsylvania School of Dentistry also required that a student be 21 years of age to graduate. He was only 20 when his two years of schooling ended. Without a diploma in hand, the State of Georgia would not issue him a license to practice dentistry, which meant that he had five months to wait before he could become a full-fledged dentist.

He made good use of the time, according to his future paramour, Kate Elder. In a series of interviews published in the Brewery Gulch Gazette, Kate later claimed that Holliday made a post-graduation journey to St. Louis where he practiced dentistry for awhile on Fourth Street near the Planter’s Hotel. The address she gives perhaps substantiates her story, as one of John Henry’s classmates, Auguste Jameson Fuches, returned to his hometown of St. Louis to practice dentistry at that site. It’s likely the two students were friends, as they would have been seated just one chair apart in the alphabetical arrangement of the lecture rooms at the dental school, and had even chosen the same topic for their doctoral theses. Kate’s story might have seemed a wild imagining but for that dental practice address. And if the story is true, then it’s also likely that Kate and John Henry first met there in St. Louis as she claims, before his grandmother’s illness supposedly called him home to Atlanta.

She was wrong about the illness though—as both of John Henry’s grandmothers were already deceased long before he left Georgia for dental school—but correct in mentioning that upon his grandmother’s death he inherited his family fortune. Though there wasn’t all that much fortune left, it was the Cloud-McKey money that came through his mother and grandmother that had created John Henry’s inheritance, and that he claimed on his twenty-first birthday that August of 1872. His father filed the legal paperwork soon after, releasing his own guardianship of the Iron Front building and the Lowndes County land by selling those properties to his now come-of-age son. All at once, John Henry was both a licensed dentist and a landed gentleman, ready to enter into his adult life.

He started his new career in Atlanta, working with Doctor Arthur C. Ford who was soon to be elected as President of the Georgia Dental Association. Doctor Ford was a promoter of young dentists, and entrusted John Henry with running his practice while he traveled to Virginia to attend a dental convention—conveniently leaving the heat and smells of Atlanta in August to the younger man. While John Henry worked in Doctor Ford’s Atlanta practice, he took up residence at the Forrest Avenue home of his uncle, Doctor John Stiles Holliday. There is no record of how long he worked for Doctor Ford or lived with his Atlanta relatives, but it is known that he made a trip to his old hometown of Griffin in November of that year, where he registered the deed to his Iron Front building.

Griffin lies 40 miles south of Atlanta, a five-hour trip in those days on the Macon and Western Railroad. Halfway between those two cities is Jonesboro, and it is probable that John Henry found himself there again in December of that year, attending yet another family funeral. Mattie’s father, Rob Holliday, died at his Jonesboro home that Christmas Eve, and was buried 10 miles away in the family plot in the Fayetteville Cemetery. According to Mattie’s recollections, her father had not been strong since his service in the Confederate States Army, and the weather that year may have hastened his passing. The winter of 1872-73 was one of the hardest on record.

That was not the last family funeral for John Henry that cold winter. On January 13, less than a month after the passing of his Uncle Rob, John Henry’s foster brother Francisco Hidalgo died of consumption in the little town of Jenkinsburg outside of Griffin. Francisco was only 38 years old at his death, leaving behind a wife, six children, and a newborn baby daughter. He was buried in the little Jenkinsburg Cemetery, his granite headstone inscribed with his adopted birth date of July 4, 1835.

It is certain that John Henry attended that funeral, as he used the trip through Griffin to take care of a surprising bit of personal business—selling his half of the Iron Front building. The deed of sale to local liquor store owner N.G. Phillips was executed on January 14, 1873, for the high price of $1800. It was the most money the property would bring for over 30 years.

His movements for the remainder of his stay in Georgia are unknown. Did he then return to Atlanta, or use the money to start his own dental practice in Griffin as many old-timers there claim? As late as the 1930s, there was still evidence of a dental office in a second floor room in what had been the McKey’s western half of the Iron Front building. John Henry could have sold his own property, then leased a small space in his uncle’s half of the building, having the word “Dentist” painted on the long window that faced onto Solomon Street. But whether he returned to Atlanta or stayed on in Griffin, he wasn’t long in either place. By October of that year he was in Dallas, Texas, practicing dentistry and getting into trouble over gambling.

What made him leave Georgia so suddenly? Was it sadness over the double-mourning of his uncle and foster brother? Was it the early signs of the illness that would eventually take his own life? Was it a frustrated romance with Mattie, as some have proposed? Or all of these, that set him on a desperate run from the law? It was 50 years after his death before the stories began of his leaving home for the dry plains of the West in search of a cure for consumption. And not until the middle of the twentieth century did the supposed love affair with Mattie become a popular explanation for his wanderings in the West.

But there are clues that may give a partial answer, like Bat Masterson’s tale of a shooting in south Georgia that precipitated John Henry’s exodus and started the legend of Doc Holliday.

It was the indiscriminate killing of some negroes in the little Georgia village in which he lived was what first caused him to leave his home. Near the little town in which Holliday was raised, there flowed a small river in which the white boys of the village, as well as the black ones, used to go in swimming together. The white boys finally decided that the negroes would have to find a swimming place elsewhere, and notified them to that effect…One beautiful Sunday afternoon, while an unusually large number of negroes were swimming at the point of dispute, Holliday appeared on the river bank with a double-barrelled shot-gun in his hands, and, pointing it in the direction of the swimmers, ordered them out of the river.

“Get out and be quick about it,” was his preemptory command. . . . Holliday waited until he got a bunch of them together, and then turned loose with both barrels, killing two outright, and wounding several others. . . .

The shooting . . . was entirely unjustifiable, as the negroes were on the run . . . but the authorities evidently thought otherwise, for nothing was ever done about the matter. . . .

His family, however, thought it would be best for him to go away for a while and allow the thing to die out; so he accordingly pulled up stakes and went to Dallas, Texas, where he hung out his professional sign . . . This was in the early seventies.

It is difficult to accept Bat’s story at face value, but impossible to dismiss it. When the McKey family was later questioned about the shooting incident, they said only that John Henry shot over the boys’ heads and that no one was killed. But they did not deny the shooting. There was, after all, a swimming hole on a small river near the little village where Holliday was raised, as Bat had said. And the McKeys happened to own the land along the banks of the Withlacoochee where the swimming hole had been cleared. As kin to the landowners, John Henry would have had more right than others to order trespassers off his property.

It’s the fact that nothing came of the shooting that is difficult to explain. In the early 1870s, the Reconstruction Yankees in Georgia were keeping a close watch on race relations. Henry Holliday, who had once worked for the Freedman’s Bureau, had gone on to run for mayor of Valdosta and was a man with political clout—possibly enough to turn the eyes of the law away from his wayward son. All John Henry had to do to avoid legal trouble was to get himself safely out of Georgia.

So back to Bat’s story, and a possible run from the law that took John Henry to Texas. Such a journey would be fairly simple from south Georgia. Beside the land along the Withlacoochee, the McKeys owned a plantation in Hamilton County, Florida, just over the Georgia State line where John Henry could have found fast refuge. Once there, it was an easy ride to the railhead in Lake City and a train ticket to Tallahassee and on to Pensacola—one of the major shipping ports of the South, with regular sailings to Texas. It’s just a theory of course, like all the other theories of John Henry’s leaving Georgia, but one that seems to make sense—especially in light of an old story out of another small Georgia town.

Waycross is near to the Okefenokee Swamp in southeastern Georgia, and far from anyplace else. But that seemingly obscure spot may hold the secret to the mystery of John Henry Holliday—a secret found, then lost, in an old box. As the story goes, a Waycross antiques dealer in the 1950s was presented with an old box that had been found in the dusty attic of a house in town. Inside the box were assorted worthless items: a few photographs; a wooden cross that might have been a grave marker once; a bundle of letters postmarked Pensacola, Florida. Only the name on those letters, John Henry Holliday, made them at all interesting. The dealer recognized the name as the legendary Doc Holliday, but assumed the letters were forgeries as everyone knew that Doc went West for his health by train from Atlanta, and was never in the old port city of Pensacola. He put the box away and forgot about it. Now the story of the box is little more than a legend. But before the legend there was a life—and only John Henry himself will ever know the truth of it.

Victoria Wilcox is Founding Director of the Holliday-Dorsey-Fife House Museum in Fayettevile, Georgia. She is currently writing an epic historical novel bout the life of Doc Holliday. She lives in Fayette County with her dentist husband and their four children.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy Sarah Cranford Bradford –

– courtesy Regina C. Rapier –

– Courtesy Susie Thomas –