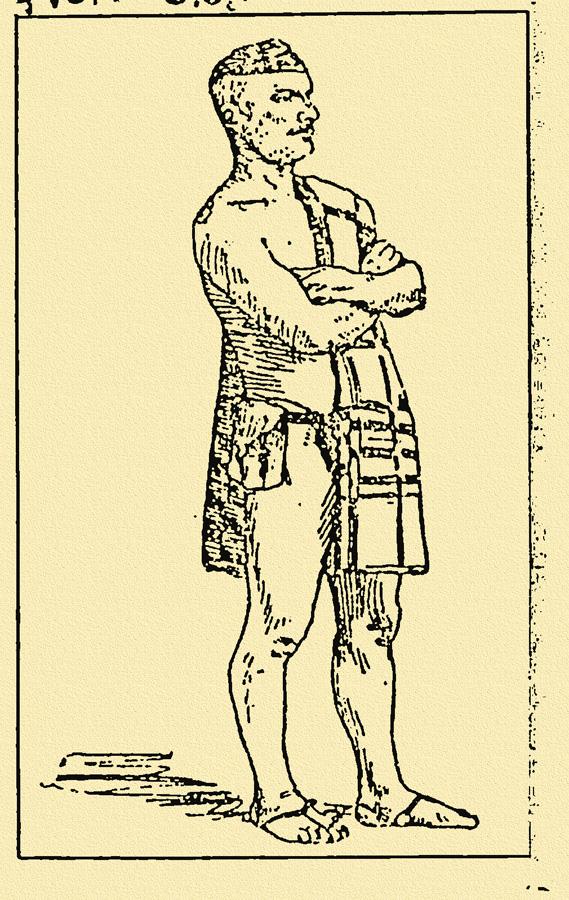

In the summer of 1891, one of Tombstone’s most infamous characters showed up in town without a gun, without a name and without clothes. That’s right, without clothes. Except for a skull cap and crude leather sandals, this handsome, blue-eyed stranger—six feet tall, slightly bearded, of fine physique and intelligent bearing—was entirely naked. He also had a darn good tan.

In the summer of 1891, one of Tombstone’s most infamous characters showed up in town without a gun, without a name and without clothes. That’s right, without clothes. Except for a skull cap and crude leather sandals, this handsome, blue-eyed stranger—six feet tall, slightly bearded, of fine physique and intelligent bearing—was entirely naked. He also had a darn good tan.

The Tombstone Prospector called him “the wild man of the weird and woolly west,” and cracked that his attire “consisted principally of a lead pencil.”

“I take pardonable pride in my cuteness,” declared the bronzed visitor, who explained that a skin disorder prevented him from adopting the uncivilized convention of clothing.

That didn’t cut it with Frank Broad, constable in the San Pedro River mill town of Charleston. With pistol drawn, Broad corralled his man, who promptly asked if newspapers had been writing about him.

“Yes,” replied Broad, “they are full of it all over the East.”

The prisoner puffed up and said, “I suppose you think you have made a big haul, but you will find yourself full for your pains.”

Broad brought the naked man to Tombstone, nine miles distant, to stand trial for indecent exposure.

His arrival touched off a sensational month of curiosity, speculation and uproarious philosophy from someone who refused to give his real name and insisted on being called O Homo.

“He has been traveling through the country stark naked,” The Prospector reported on July 27, 1891, “and although he has frightened nearly everyone by his appearance . . . he talks perfectly rational and does not appear to be out of reason.”

Far from it. O Homo was bright, well-read in Greek and Latin, able to quote Diogenes and other philosophers—and deeply thoughtful about baring every inch of his flesh.

Writing in The Prospector, which gave him almost unlimited space to air his views, O Homo penned, “The idea that poor women in New York chained to the treadmill of a labor-increasing machine, living on the crust of starvation, can make a better suit of clothing than God or nature . . . did God almighty make a mistake? . . . Zounds!”

In spite of his obvious love of nudity, O Homo was unwilling to give a straight answer to any personal question.

When he stood before the judge to plead not guilty, he was asked his home state. “Do you expect me to testify against myself?” he responded.

Authorities had given him a straw hat, flannel shirt and blue overalls, which he wore under protest. He insisted on tossing a blanket over himself so that no sign of dreaded clothing was visible.

The Prospector declared him “the sensation of the year.” Reporters dug for every morsel they could find about the cool and charming O Homo.

Following Tombstone’s lead, other Western papers took up the story. A correspondent for The San Francisco Chronicle came to Tombstone to interview the prisoner, who’d speak only after shedding his clothes.

The Chronicle reported that O Homo was uncommonly good-looking, with the body of a prize fighter and “flesh hard as iron.”

Speculation about him became a summer sport.

One report said he’d been spotted walking west from Deming, New Mexico along the railroad tracks “as naked as when born.” He carried a canteen, a razor and a piece of white cloth, which he put on when approaching a town.

Another said he’d walked up from Sonora, where Mexicans thought he was doing penance for his sins and advised him to pack a cross.

O Homo added to the circus atmosphere with various pronouncements, including that he was traveling the world on a $1 million bet.

He also spent a good amount of time chastising Constable Broad. The prisoner revealed that he’d been arrested some 40 times prior to Broad getting hold of him. But he was never tossed in jail until he came to Tombstone—“and allowed myself to become a victim of fossilized ignorance in the form of a man who is not acquainted with a solitary water hole from the alpha to the omega of liberty.”

Knowing it was sitting on a mountain of good copy, The Prospector shipped the prisoner a plug of chewing tobacco to keep him happy. The paper also published several of his teasing letters.

“Now, as I have excited a little curiosity in this quiet churchyard, I propose to offer this prize [a valuable jewel] to the man that ferrets out the mystery concerning me,” wrote O Homo on July 29.

He addressed his letter to the editor of The Daily Shoot Off, and signed it, “Yours Indecently.”

On August 1, The Prospector published several guesses as to his identity, written by the jailhouse wag himself.

They included the suggestion that he was Don Quixote looking for windmills and fair damsels and that he was Oscar Wilde looking for sunflowers.

A presidential candidate? O Homo even suggested he was the “sockless statesman from Kansas making a sneak on the White House.”

Readers sent letters to the editor positing their own theories.

“Calls himself ‘man,’ but acts like a beast, entirely devoid of modesty,” sniffed one. “Hence my reason for guessing him to be the missing link.”

Another reader proclaimed him a tramp seeking notoriety and noted that she’d come to Arizona to hide away from the world, too. “With my clothes on,” the letter-writer emphasized.

O Homo was found guilty and sentenced to 30 days. He spent his time squatting on the floor, his shoulders covered with an oversized Indian blanket, or leaning in picturesque pose against the wall of his cell. He had become so popular The Prospector, in effect, made him a columnist. His favorite topic was himself.

During his life in the wilds, O Homo said he had survived by eating a “palatable dish of mud and water,” mixed with mesquite leaves. He said the iron in the mud was the reason for his endurance, and promised to perfect his dish and “make known to all mankind the process of its manufacture.”

Among the Cheyenne tribe, O Homo was seen as the long-looked-for Indian Messiah predicted by Sitting Bull. Indians followed him in crowds, and he received the blessings of medicine men.

“They all displayed great anxiety to touch me,” he wrote, “if only the hem of my blanket, and they offered me clothing which I firmly refused, telling them that it would be an insult to the great spirit to hide the form which he gave me from his sight by a bundle of the white man’s rags.”

When the Cheyenne asked O Homo to drive the evil from an insane man, he took a bottle of chloroform and poured some over his cap. He then passed it under the nose of the man, and “saying a few Latin words, I produced a profound slumber. He awoke with reason regained.”

His writings alternated between insulting, rambling, hilarious and wise, such as when he remarked that he was the only man “in Tombstone who can truthfully say, I do not beg, steal, gamble or speculate.”

Some samples.

On the sexes: “A man’s honor and a woman’s virtue are like a fort. No matter how strongly fortified, they can be taken.”

On infamy: “I avoided settlements as much as possible for I was not seeking notoriety, but rather preferred to remain in the obscure corner of contentment, believing that the famous man is like a dog with a tin can tied to his tail.”

On The Prospector’s editor, who published one of O Homo’s letters with a portion deleted: “I can overlook the drunken blunders of a tramp printer, especially when he is in the labyrinth of foreign words, but when an editor with ruthless negligence, strips the green leaves of wisdom, tramples upon the delicate flowers of pathos, and crushes the red-cheeked fruit of humor, and then with the stump whips his jaded horse to death, I feel like gently admonishing him to return to his old trade of butchering rotten carcasses and making sausage.”

On happiness: “Reach to the most distant star and gather together the whole starry cosmos in your apron of wisdom, but know that all is but trash when compared to the brightest gem that ever adorned fair woman’s brow, the only jewel worth wearing, the smile of contentment.”

O Homo’s writings attracted wide notice, and his fame grew. C.S. Fly, known for his photographs of Tombstone characters, began selling pictures of him. Even at the then-outrageous price of $1 apiece, they became a popular novelty.

Although none of Fly’s photos can now be found, there is no doubt the naked one existed. But his true identity was never determined.

After serving his time, the colorful stranger was released. He landed in Yuma in late October and “was decently dressed and conducted himself with propriety,” according to The Yuma Sentinel.

He told the paper he was headed to Los Angeles to join a German professor on a trip “over the Colorado desert.” After departing Yuma, O Homo vanished (or did he? See sidebar).

But he wasn’t forgotten in Tombstone. For months afterward, drawn by flowery descriptions of his physique, women as far away as California wrote to O Homo, asking him to take a wife, namely the letter-writer.

If Wyatt Earp ever achieved that kind of adoration, the history books missed it.

Leo Banks is a freelance writer living in Tucson, Arizona. He was previously a correspondent for both the Boston Globe and Los Angeles Times. His articles have appeared in Sports Illustrated, The Wall Street Journal, Arizona Highways, National Geographic Traveler and others. He has also written several books on Arizona history, including Double Cross, published in 2001 by Arizona Highways Books, about the Apache wars.

Photo Gallery

– Donkey photo courtesy Gary S. McLelland and Stephen & Marge Elliott; right photo, Tombstone Heritage Museu –

– Courtesy of Gary s. McClelland –