Ask most Americans to name a few intrepid lawmen from the nineteenth century, and they are almost certain to list Wild Bill Hickok, Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp.

Ask most Americans to name a few intrepid lawmen from the nineteenth century, and they are almost certain to list Wild Bill Hickok, Bat Masterson and Wyatt Earp.

These heroes of yesteryear epitomize the bold lawmen who tamed the frontier with their six-guns and tin stars. For nearly a century, Hollywood has immortalized these valiant peacekeepers, embellishing their reputations until it is often difficult to separate fact from fantasy.

Query other Americans about which Western town was the most lawless, and they’re apt to say DodgeCity, Tombstone, or Deadwood. Thanks to the movies and the dime novels before them, the mention of these old cow and mining towns brings to mind images of gunslingers, drunken cowboys, gamblers and a gutsy sheriff or marshal who brought them to heel.

Yet, there were more wild towns and daring lawmen than those that are most often brought to mind.

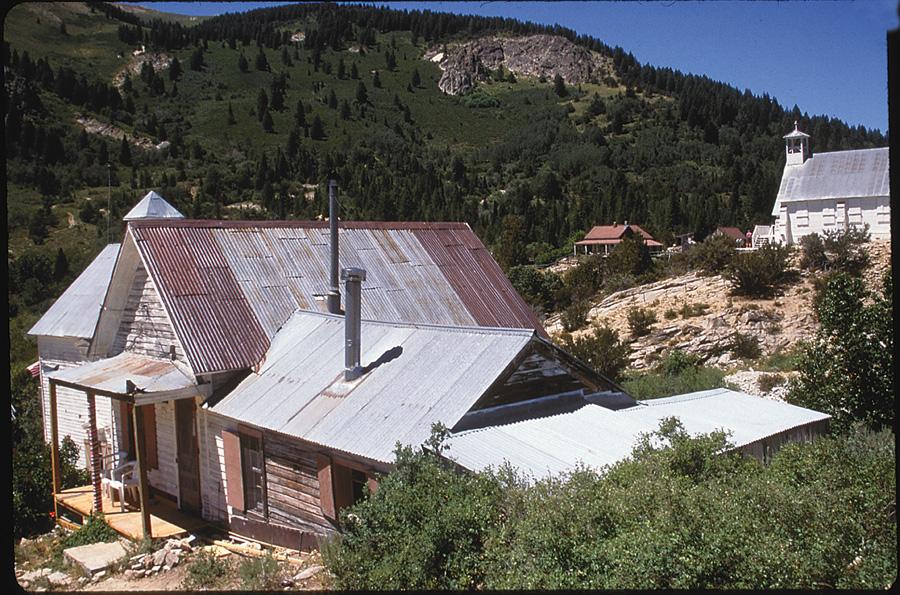

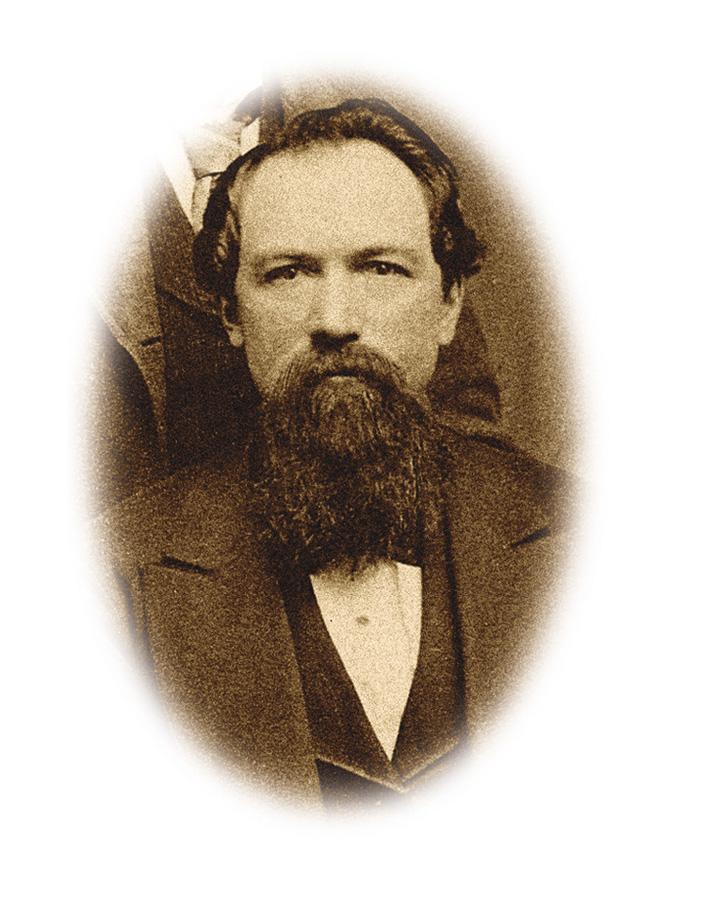

In the second half of the nineteenth century, the Idaho Territory had its share of rowdy towns. The mining centers of Idaho City and Silver City, competed with Deadwood and Tombstone not only for the amount of rich ore their citizens produced, but also for the number of hard men they attracted. While Wyatt Earp and his brothers held sway in the Arizona desert, an equally fearless lawman faced down desperados in Idaho. His name was Orlando “Rube” Robbins.

Robbins was born in Maine on August 30, 1836. When he was a teenager, he acquired a yoke of oxen, which he valued highly. He used the oxen on his family’s farm and occasionally earned money by hiring them out to neighbors. When Robbins was 17 years old, his father sold the oxen without asking his son for permission. Raging with anger, the young man bid his father good riddance and left home for good.

Robbins eventually found his way to the California mining camps in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada Mountains. When he was 25, gold strikes along Idaho’s Clearwater River and in Florence Basin (a few miles northeast of Riggins, Idaho) lured him away from California. Two years later, in August 1863, he relocated again, drifting south to the new diggings in Boise Basin (about 20 miles northeast of modern-day Boise).

A year old at the time Robbins arrived, the Boise Basin gold rush was producing the largest stampede of miners and hangers-on since the heyday of California’s Mother Lode. Numerous mining camps—they quickly grew into small cities—dotted the landscape, sporting names such as Placerville, Centerville, and West Bannack. Robbins gravitated to West Bannack, which was the fastest growing of the towns with over 6,100 people. Wanting a name that fit West Bannack’s prominence as the largest settlement in the Pacific Northwest, the Territorial Legislature soon re-christened it Idaho City.

At the time Robbins moved to the boomtown, it boasted a hospital, a theater, two bowling alleys, four sawmills, a mattress factory, nine restaurants, two churches, four breweries, and 25 saloons, all opened within the first 12 months of its founding. The town also had 15 doctors and more than two dozen lawyers. But what Idaho City needed more than a horde of sawbones and shysters was law and order. And found it in Rube Robbins. In 1864 he became a deputy sheriff.

With the Civil War raging in the East, the Boise Basin miners polarized around the Union and Confederate causes. Fueled by whiskey, Northern and Southern sympathizers often bloodied one another with fists, knives, and sometimes guns as they used force to show their opinions. Many an evening, Robbins had to lock up a drunken loudmouth who was threatening to punch or shoot to demonstrate his political beliefs to an equally intoxicated opponent (who was just as certain that God was on his side).

Early one July, the town’s Southern contingent vowed that it would not allow any Yankee to sing the “Star Spangled Banner” on Indepen-dence Day. Learning of the bluster, Robbins became infuriated. He was for the Union, and no mob of Rebel-leaning rabble was going to curtail his free speech.

On July 4, he stepped into a barroom overflowing with Southerners. Ignoring the drunken toasts to Jefferson Davis and the Confederate cause, he walked over to a billiard table, climbed atop its green felt, and pulled his revolvers. As everyone stared at the two cap-and-ball pistols, the saloon fell as quiet as a prayer meeting.

“Oh, say can you see by the dawn’s ear-ly light, . . .” The deputy’s baritone voice boomed out the song’s three-quarter time.

“What so proud-ly we hail’d at the twi-light’s last gleam-ing. . . ?” Robbins watched the crowd as he sang, but no one so much as twitched an eyelash.

“. . . O’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?”

With his eyes still locked on the crowd, Robbins holstered his guns and hopped off the table. In place of his singing, a ponderous silence filled the barroom. Pushing his way through a sea of glares, the lawman walked to the front door and into the street. Not one Southerner made a move to stop him.

Robbins’ reputation soon earned him a job in Boise, where he served first as a deputy sheriff and then as a United States marshal.

In late February 1868, miners working the Golden Chariot Mine beneath Silver City—a boomtown located in the Owyhee Mountains about 60 miles southwest of Boise—burrowed into a shaft belonging to the Ida Elmore Mine. For several weeks, the two factions cussed and fumed, each side accusing the other of tunneling beyond its claim.

On March 25, tensions came to a head when a party of armed Golden Chariot miners invaded the Ida Elmore shaft. A subterranean gunfight soon erupted, and then escalated until 100 men were engaged in the battle, which was known as the Owyhee War. For three days, the two underground armies fired at each other, spraying so much lead into the Ida Elmore’s support timbers that the mine nearly collapsed.

When news of the war reached Idaho’s territorial governor, he issued an order demanding that the two sides immediately end their fighting and settle their feud in court. The job of delivering the governor’s proclamation and forcing a truce was given to Orlando “Rube” Robbins.

Averaging an amazingly fast 10 miles per hour over roads that were mud-cloaked by the spring rains and mountain snowmelt, the lone deputy rode from Boise to Silver City in six hours. Soon after arriving, Robbins brought the heads of the warring parties together and read the governor’s edict. No doubt he also informed them that he would personally ensure that the proclamation was obeyed. Knowing his reputation, the Golden Chariot and Ida Elmore owners took the deputy at his word. After calling off their gunmen, the adversaries drew up new boundaries for their mines and never needed to go to court. Robbins had settled the entire affair in a single day.

Facing down drunks and arbitrating disputes were not the only things the deputy excelled at. He also knew how to catch criminals. In February 1876, after six bandits held up the Silver City stage as it neared Boise, Robbins had them in jail within two days of the robbery.

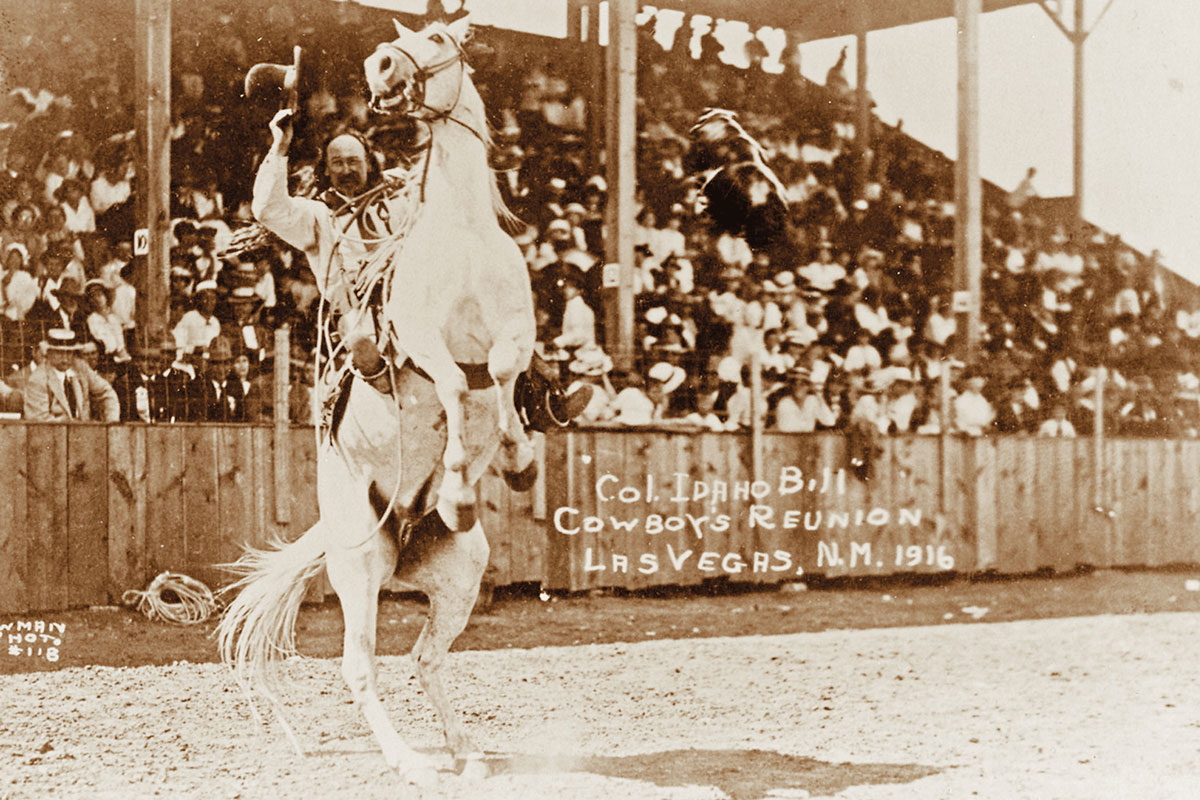

In addition to his duties in law enforcement, Robbins also held the rank of colonel in the territorial militia and was head of scouts. During Idaho’s Camas War in the late 1870s, he and his command were part of a larger U.S. Army force that, pursued a band of Bannock and Paiute Indians, led by a Paiute war chief named Egan, into the Owyhee badlands southwest of Silver City (near the Idaho-Oregon border). For nearly two weeks, the Army chased the hostiles across the high desert, some days riding 50 miles.

In late June 1887, as was later recounted by a militia eyewitness, Colonel Robbins and four of his troop were riding over a ridge when they were jumped by a party of Bannocks that included Chief Egan. Outnumbered by the warriors, the scouts spurred their horses to a gallop, trying to reach the Army lines. The Indians pressed the pursuit, firing as they rode. Just when it appeared the militiamen would keep their scalps, the Bannocks wounded a scout named Bill Myers and killed his horse. Hearing Myers’ cry for help, Robbins wheeled about to go to his rescue.

While Robbins raced toward the fallen trooper, Chief Egan whipped more speed out of his horse in order to cut between them. As the famed lawman and Indian leader drew closer together, they finally recognized one another. Their warrior spirits inflamed, the two combatants charged each other with their Winchesters blazing. Acting like Knights of the Round Table on a battleground in the Middle Ages, Robbins and Egan fired lead with as much abandon as their medieval counterparts had swung sword and mace.

Their rifles empty, the chief and Indian fighter drew their pistols. Sitting atop his dancing steed, Robbins blasted away with his revolvers, impervious to the lead that tore through his clothes and nicked his finger. Chief Egan also showed his mettle, deftly using his horse for cover as he dodged Robbins’ bullets. And then one of the lawman’s shots found its mark, hitting Egan in the wrist and knocking him off his mount. Quickly regaining his senses, the chief scrambled to his feet, ready for a fight to the death. But before Robbins could renew his aim, trooper Myers raised his gun and shot Egan in the chest.

Leaving the gravely wounded chief to his tribesmen, Robbins helped Myers up behind his saddle and escaped.

Seven weeks later, Robbins again demonstrated his cool head. He was crossing the Snake River in a rowboat with an Army lieutenant named W. R. Parnell, a bugler, and two cavalrymen, when a horse they had tethered to their boat panicked. As the soldiers tried to free the animal, it bumped their boat, spilling everyone into the water. While Lieutenant Parnell and the bugler began drifting with the current, Robbins helped one of the cavalrymen climb onto the overturned hull. The other cavalryman caught the horse’s tail and hung on as it swam to shore.

Seeing the bugler start to founder, Robbins abandoned the safety of the rowboat and went to his aid. No sooner had he maneuvered the bugler into the shallows than Robbins noticed the lieutenant was beginning to tire. Once more, he dove into the river, reaching Parnell as he was about to go under. Robbins kept the sputtering officer afloat until another boat came to their rescue.

During the 1880s and ’90s, Robbins continued to pursue desperadoes across southern Idaho. In August 1882, shortly before his forty-sixth birthday, he arrested the outlaw Charley Chambers after covering 1,280 miles in just 13 days. Any criminal having Robbins on his trail might as well consider himself already behind bars.

Unlike many lawmen of his day, Robbins had a life apart from gunplay and daring. When he was in his thirties, he became a Christian and joined the temperance movement. Following his baptism in the Boise River, he was elected president of the Methodist Church Sunday School. He also served a term in the Idaho Territorial Legislature, and some years later gained appointment as its Sergeant at Arms.

When Robbins was in his late sixties, he transported prisoners for the Idaho State Penitentiary. Although he escorted men who were often one-third his age, he never allowed any of them to get away.

Idaho’s most famous lawman died of a heart attack on May 1, 1908. During his funeral, numerous dignitaries paid him homage, each attempting to take his measure. But none of these orations came close to the tribute spoken years earlier by the outlaw Cherokee Bob.

As he lay bleeding to death from Robbins’ gunshot, the bandit said the marshal never jumped to the side after shooting, but “always sprang through the smoke [of his revolver] and advanced upon his opponent, firing as he came.”

Like Hickok, Masterson and the Earp brothers, Orlando “Rube” Robbins was similar to a paladin of the Old West and an honor to all Americans, “in the land of the brave and the home of the free.”

R. G. Robertson a Vietnam veteran, former partner at Hambrecht & Quist in San Francisco and retired options market maker on the Pacific Stock Exchange is also the author of three books, the most recent being Rotting Face: Small Pox and the American Indian. R.G. and his wife, Karen, divide their time between Sun Valley, Idaho, and Scottsdale, Arizona.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesey the author –

– Idaho State Historical Society –