Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid–The Way It Should Be Seen

Fifty years after its first release, the film’s recent version is considered the best.

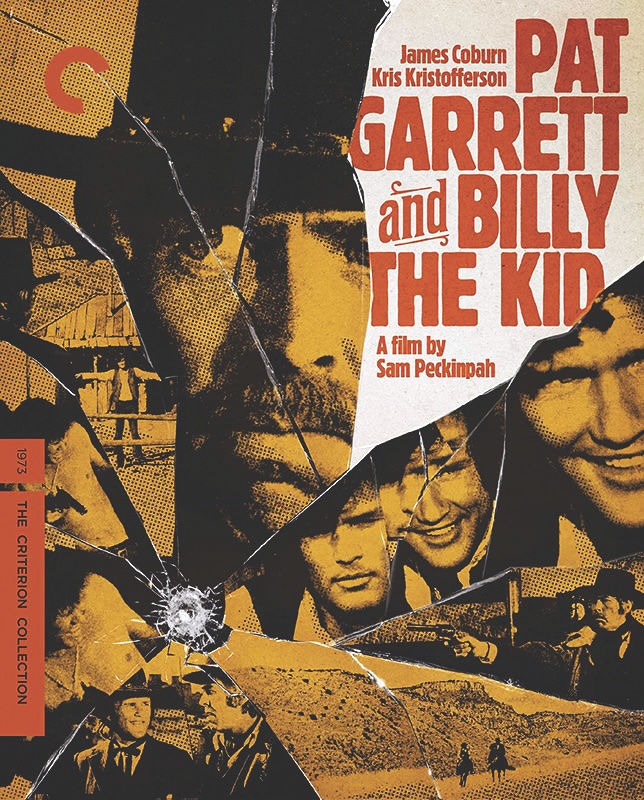

Half a century after its theatrical release, with the new Criterion version, Sam Peckinpah’s final Western, Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, can finally be seen—as far as we can tell—the way Sam wanted it to be seen. It is certainly the best version there has ever been. And there have been many versions: Sam’s first and second preview cuts, both about 122 minutes, but with a lot of different footage; the 106-minute theatrical release; the 96-minute Jim Aubrey cut; the broadcast TV cut; the Z-Channel cut; and finally, both supervised by Emmy-winning editor and author Paul Seydor, the 2005 and new, 117-minute 2024 cuts.

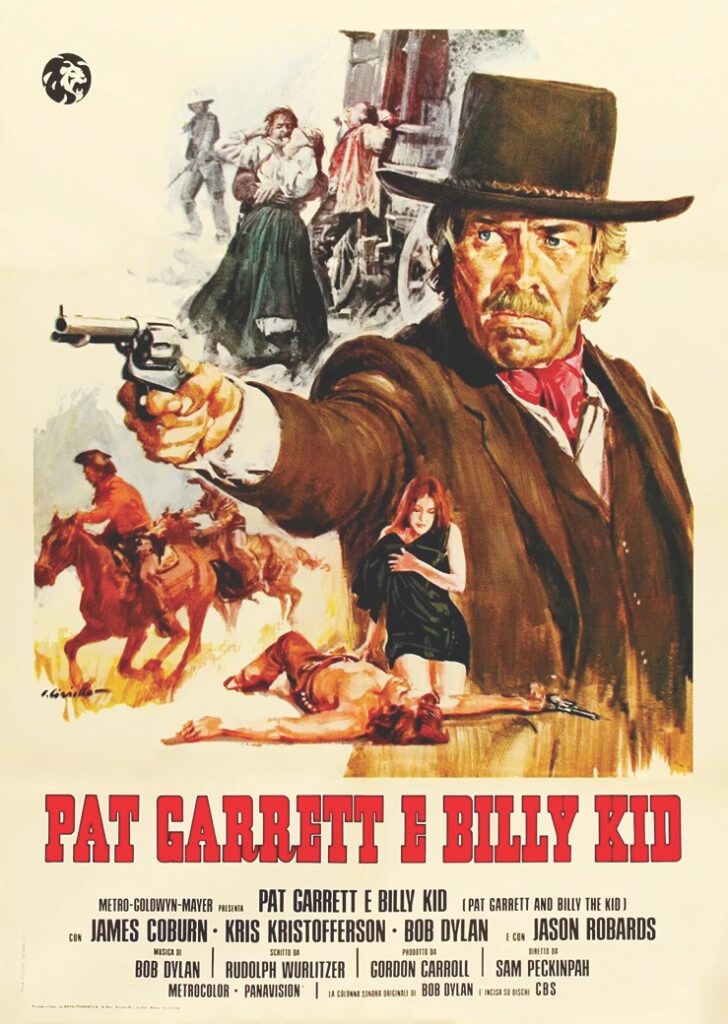

Peckinpah was eager to tell the story of Pat and Billy, going back at least to 1957, when he was hired to script One-Eyed Jacks, then fired by Marlon Brando. Fifteen years later, Rudy Wurlitzer’s Pat Garrett screenplay was snapped up by MGM, and they wanted Peckinpah because they wanted another Wild Bunch. If they’d actually read the script, they might have noticed that while Wild Bunch, Major Dundee, et al were all about driven men on a mission, Garrett was an elegiac character piece which doesn’t “go” anywhere. As producer and close Peckinpah ally Gordon Carroll said, “It’s a movie about a man that doesn’t want to run, pursued by a man who doesn’t want to catch him.” Or as the real Billy himself was quoted, “I am not going to leave the country, and I am not going to reform, neither am I going to be taken alive again.” It opens in Fort Sumer, New Mexico, ends in Fort Sumner, and mostly takes place in and around Fort Sumner, with a brief excursion to Old Mexico.

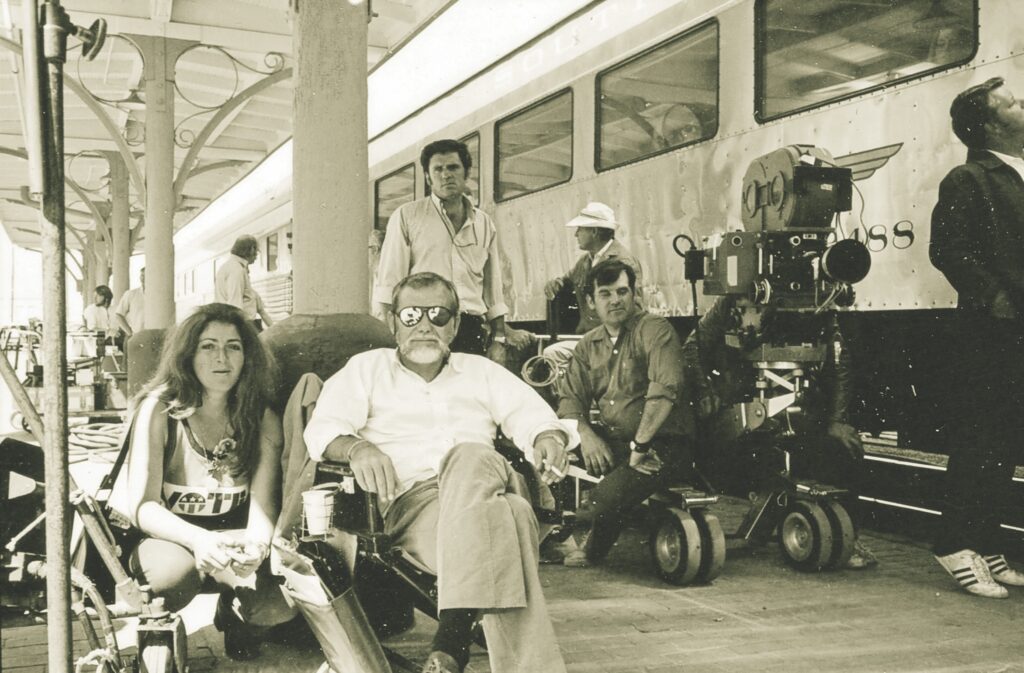

The 1970s was a tough time to make movies, especially in the studio system, particularly at MGM. The Hollywood one-time jewel was nearly bankrupt in 1969 when former TV executive Jim “the smiling cobra” Aubrey was installed as president. To cut costs and produce income, Aubrey cancelled a dozen green-lit films, sold off acres of studio backlot, auctioned their costumes and props, and began building the MGM Grand in Las Vegas.

It was an even tougher time for Westerns: Katy Haber, who’d assisted Peckinpah on Straw Dogs, Junior Bonner and The Getaway, wasn’t available for Garrett because she was in Spain, on Sam Fuller’s Western, Riata. But in mid-shoot, Haber recalls, “Paramount decided that the film didn’t cut together, canceled the production and we were all sent home,” making her available, a little late, for Garrett. Another Western’s production problems had a direct bearing on Garrett. Seydor explains, “Aubrey wanted a film…he could put into theaters that summer. That was supposed to be The Man Who Loved Cat Dancing.” There were delays due to a switch of directors, then a stunt injury to star Burt Reynolds, then the suspicious death of Sarah Miles’s manager/lover. “They couldn’t finish that up. So they ramped up the release of Pat Garrett.”

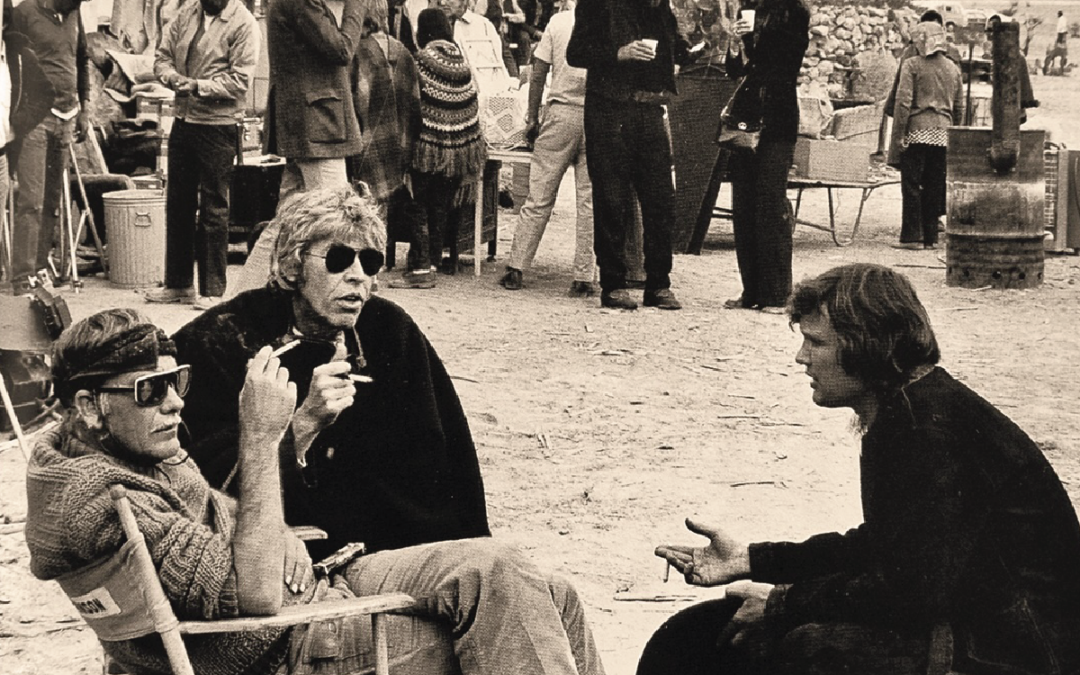

And Peckinpah was not a man to be rushed. Charles Martin Smith remembers, “I ended up just sitting in Durango for weeks, because he’d plan to shoot a scene that I was in, and then shoot some other stuff.” Smith had a nice role in Culpepper Cattle Company and had just finished American Graffiti. “I went in on the role of Alias, the part that [Bob] Dylan played. I auditioned for Sam. He was volatile, unpredictable. And he explained how he had a bunker in Mexico. ‘We’re gonna shoot this movie in Mexico, and when the shit hits the fan, that bunker’s where [I’m[ gonna go!’ I’m a 19-year-old kid thinking, I might be over my head with this guy.”

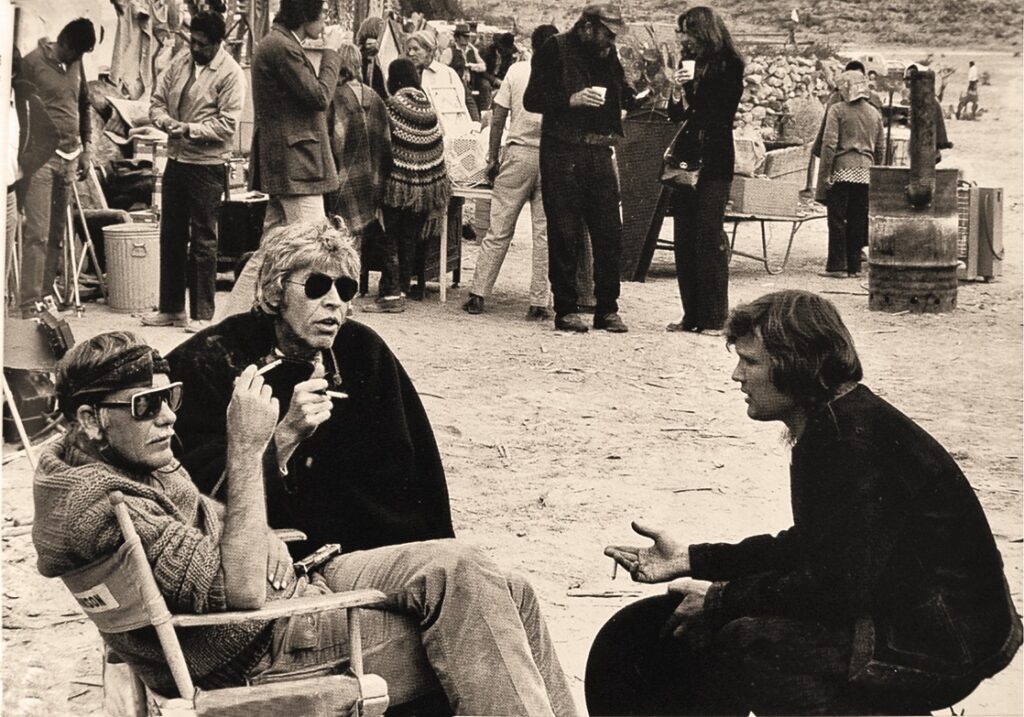

Other issues slowed progress. Shooting in dusty, primitive Durango, Peckinpah wanted a Panavision technician along, but Aubrey refused. Thus they shot a week’s worth of scenes out of focus. “We had a lot of reshoots,” Haber recalls, “because the 45-millimeter lens wasn’t working.” Aubrey forbade any reshoots; “he wanted all the meaningful stuff cut out of the film. So we shot on Sundays, with no pay, without anybody else’s knowledge.”

Dylan wrote Knocking on Heaven’s Door and other powerful songs for the film, but casting the inexperienced and otherworldly Dylan as Alias didn’t speed up the shoot. “We’ve been waiting days to get a ‘golden hour’ shot,” Haber says. “Kristofferson’s in the foreground, and all of a sudden, Harry Dean Stanton and Dylan are jogging in the background! Sam goes, ‘Cut!’ Harry comes running up, panic on his face. ‘Oh, my God, Sam, I’m so sorry! I saw Dylan running, and I was trying to stop him.’ Dylan was not easy to shoot because he had no concept of film whatsoever. Ironically, shortly after the end of Pat Garrett, Dylan directed his first and only film, Renaldo and Clara (1978).”

Even in the smallest roles, the cast is brimming with great Westerners, and what the film lacks in plot, it makes up for with memorable death scenes for Slim Pickens, Jack Elam, L.Q. Jones, R.G. Armstrong, Matt Clark and youngsters like Smith, who remembers fondly, “I got the full Wild Bunch treatment, with the squibs going off and everything!

“Kris really befriended me, and then 40 years later, I ended up directing him in Dolphin Tail; we’d sit around on-set and talk about Sam. Coburn was a very grand Hollywood actor of the old school. He always smoked a cigarette in a long cigarette holder.”

“What pisses me off about people calling [the theatrical release] a butchered version,” Seydor bristles, “is that film is magnificently cut by men who were real artists.” Indeed, Peckinpah’s editors, led by Roger Spottiswood, later the Emmy-nominated director of And the Band Played On, tightened the often-sluggish pre-view versions, and by removing scenes that didn’t advance the core narrative, were able to preserve the story, the performances, the lyrical moments, within the imposed running-time, preventing Aubrey from substituting his own cut.

The crucial loss was the 1908 flash-forward opening, where Pat is assassinated by someone we’ll meet as the film progresses, intercut with Pat’s guardedly friendly 1881 visit to Billy at Fort Sumner, warning him to head to Mexico. It is cinematically the high point of the film, elevating it from narrative to fine art.

Ironically, a true butchering, censoring the sex and violence for network TV, so shortened the film that previously cut scenes—Garrett with Barry Sullivan as Chisum, Garrett’s scene with his wife, Billy romancing Martha Coolidge as Maria—were added. When Z-Channel’s Jerry Harvey heard about the missing prologue, Haber supplied it. “Every night when we finished editing, Sam hid the print in the fridge so that nobody could get to it.” Other scenes, one featuring Dub Taylor and Elisha Cook, Jr., are now part of the film for the first time.

It’s taken so long to get the film right that Smith, the youngest person involved, has retired. “I was fascinated by the way Sam ran the set, his meticulousness, his attention to detail. Sam would be so careful about where that camera was, exactly what it was seeing, what was at the edge of the frame. Every shot was like a painting.”

Blu-Ray REVIEW

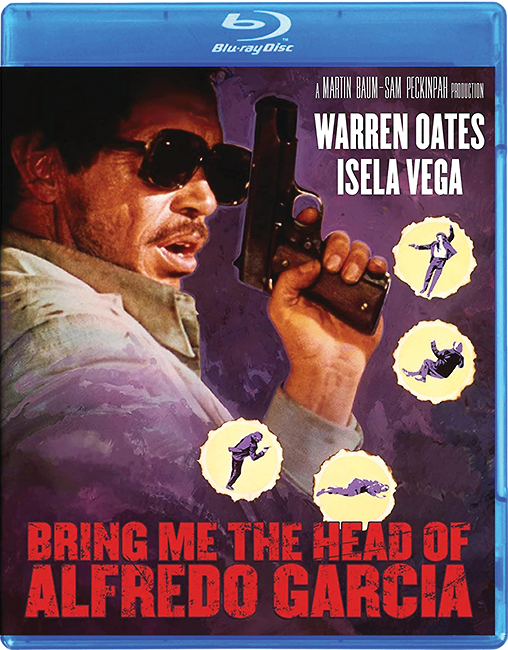

BRING ME THE HEAD OF ALFREDO GARCIA

(United Artists, 1974) Kino-Lorber Blu-Ray $29.95

Following the nightmare of making Pat Garrett & Billy the Kid, Sam Peckinpah gave audiences a nightmare, Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia, starring Warren Oates in a two-hour impersonation of Peckinpah, down to sleeping in sunglasses. A nobleman’s daughter is impregnated, and saloon-pianist Oates is on the hunt for that noggin. With enough rambling, over-the-top violence, and tear-off-the-top nudity to be a Peckinpah parody, Alfredo is a guilty pleasure about assigning guilt, and a parable about filmmaking. Gig Young, Robert Webber and the rest of the prissy bad guys are nothing like gangsters, but precisely like studio executives, who have hired Oates to deliver something so disgusting symbolically the re-edited Pat Garrett—that Oates spends much of his time fighting the flies and the stink.