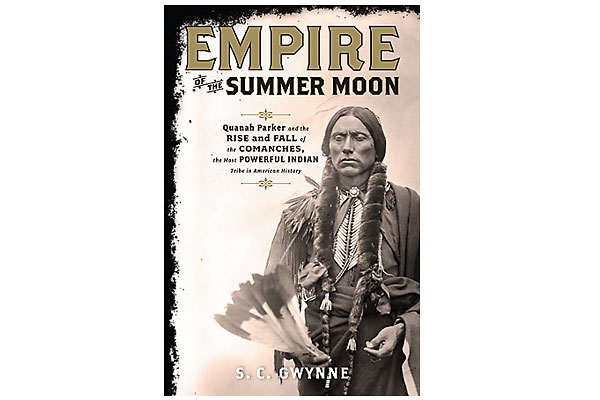

The year 1875 was a watershed for the war chief known as Quanah. Before that time, his Quahadi Comanches were one of the fiercest, toughest and anti-white Indian bands. Quanah’s hatred fueled that fire.

The year 1875 was a watershed for the war chief known as Quanah. Before that time, his Quahadi Comanches were one of the fiercest, toughest and anti-white Indian bands. Quanah’s hatred fueled that fire.

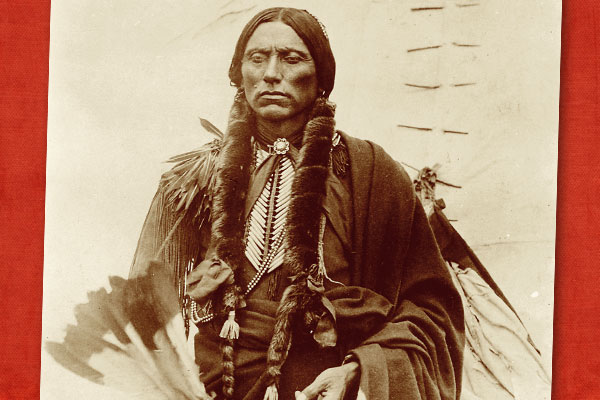

The mixed-race son of Peta Nocona and captive white Cynthia Ann Parker, Quanah—aged between 23 and 27—bore grudges. The U.S. Army had defeated his father, and captured his mother and sister, in the 1860s. Whites had killed other relatives and friends of his.

During the 1870s, settlers and military incursions grabbed much Comanche land in Texas. On June 27, 1874, Quanah led about 250 Cheyenne and Comanche warriors against 28 buffalo hunters at Adobe Walls. What should have been a slaughter turned into defeat. A wounded Quanah withdrew with his men.

The Comanches’ last gasp came the next year, during the Red River War in the Texas Panhandle. Colonel Ranald Mackenzie’s brutal tactic of destroying Comanche homes and supplies forced most bands onto the reservation at Fort Sill in modern-day Oklahoma.

Quanah’s group largely stayed out of the war; their cat-and-mouse strategy kept them out of reach of the Army. They were tired, hungry and desperate—and the last large Comanche band on the run.

When Mackenzie sent a peace commission to meet with the hostile Quanah, the troops got a pleasant surprise. The Comanches greeted them with honor. Quanah’s prayer to the Great Spirit had revealed a howling wolf and an eagle that lit out toward Fort Sill—signs that told Quanah to surrender.

On May 6, 1875, Quanah and around 400 Quahadis walked to Fort Sill. When they arrived nearly a month later, Quanah was transformed. He soon began calling himself Quanah Parker, after his mother, to indicate he was of the two worlds. Determined for his peopleto thrive, he took the white man’s road of farming and ranching.

Quanah arrived on the reservation just one of several Comanche leaders. But his close work with the whites and his success in peacefully bringing renegade Comanches to the reservation earned him respect from Mackenzie. The two fighting men’s fascinating relationship certainly helped Quanah move up in power. By 1880, Quanah was the recognized head of the Quahadis—he eventually dubbed himself chief of all the Comanches.

In his later years, Quanah lived in a luxurious wood frame house, where he greeted important visitors from around the world, including President Theodore Roosevelt. He refused to speak about his warrior days, but he gladly talked about the opportunities for his people in the white man’s world.

After Quanah died in 1911, his body was buried next to his mother’s grave in the Fort Sill Cemetery. He had reinvented himself, and his people, in an effort to survive. He succeeded.