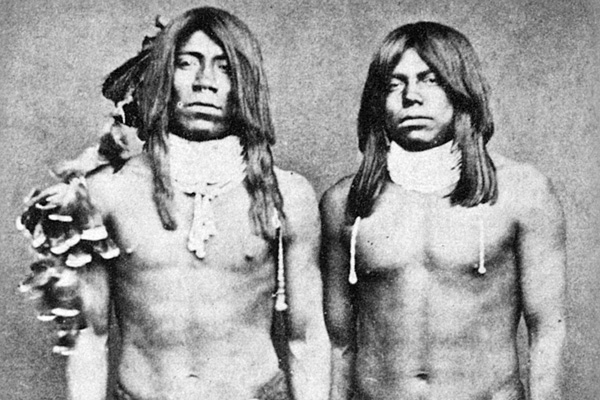

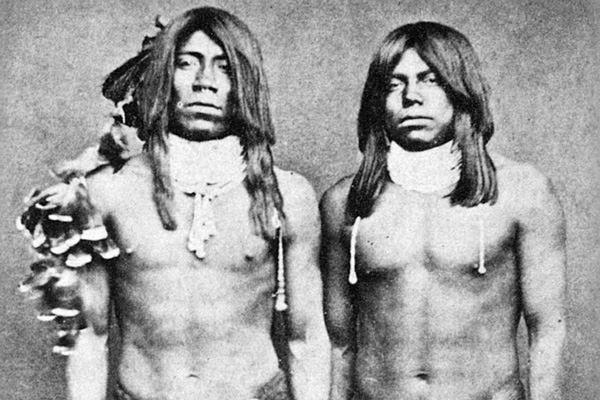

For several hundred years the Yuma Indians had resided along the Lower Colorado River. They were of Hokan stock, primarily farmers who benefitted from the Colorado River’s annual floods. The Yuma were also related to the upriver Mohave Indians, and at times, allied themselves with them in wars against the Pima and Maricopa of the Gila River Valley.

For several hundred years the Yuma Indians had resided along the Lower Colorado River. They were of Hokan stock, primarily farmers who benefitted from the Colorado River’s annual floods. The Yuma were also related to the upriver Mohave Indians, and at times, allied themselves with them in wars against the Pima and Maricopa of the Gila River Valley.

The Yumas’ first prolonged contact with white men came in the early 1770s. The noted Spanish leader, Juan Bautista de Anza, hoping to keep the El Camino del Diablo open to California, left behind a number of Mexicans to settle among the Yuma. For a few years all went well. But in 1781 trouble broke out, and in the uprising that followed, the Mexicans were all killed. For 67 years the El Camino del Diablo remained closed.

Nonetheless, the Yuma did not remain hostile to all whites. In 1826, fur trappers Ewing Young and James Ohio Pattie, on separate expeditions, described them as friendly. Twenty-two years later, gold was discovered in California; within months, hundreds of Mexicans from the state of Sonora were streaming up El Camino del Diablo and across the Colorado River. The Yuma allowed them to pass without trouble.

Many Americans were also fording the Colorado. On January 1, 1850, a party of six led by Dr. A.L. Lincoln, arrived at the junction of the Colorado and Gila Rivers from the west. Dr. Lincoln was a native of Illinois and a relative of President Abraham Lincoln. He had been living in Mexico when gold was discovered at Sutter’s Mill. After trekking to California and failing to make his strike, he returned to the Colorado-Gila crossing to try his hand at operating a ferry.

Lincoln made a shrewd move and was soon transporting hun-dreds of Sonorans and Americans across the Colorado River each week, charging one dollar per passenger, pack animal, or pack. His relations with the Yuma, who possessed almost no firearms, were good, and within a month he had collected a sack of silver coins and another of gold dust. But the traffic was so heavy he and his men could not manage alone. Help arrived in February. Eight more Americans led by John J. Glanton bought into the ferry and became full partners. In the reorganization that fol-lowed, Glanton replaced Lincoln as ferry boss.

This would prove most unfortunate for Lincoln and his men as Glanton was a drunk who hated Indians. Yet the partnership con-tinued to make so much money that everyone, including Lincoln, was satisfied with the arrangement.

All that changed in March when a party of Americans, led by a Mexican War general named Anderson, arrived at the crossing. As was often the case, even when dealing with Americans, Glanton behaved arrogantly. So angered was General Anderson by Glanton’s treatment that he left the Yuma Indians with a boat and a certificate guaranteeing them the right to operate a ferry on the Colorado at a crossing known as Algodones, 10 miles downstream. The Yuma were to charge the same fees as Glanton.

A few weeks later, another party of 14 Americans was approaching the Colorado along the Gila River when they encountered an Indian who informed them that provisions and animals awaited them at Glanton’s Ferry. The news was well received, and a member of the party named Anderson (there are no less than three Andersons in this account) decided to strike out ahead in hope of returning the next day with badly needed supplies.

Late on the night of April 23, he returned to camp to breathlessly announce that he was lucky to be alive. Worse, he had reason to believe all the Americans at Glanton’s Ferry were dead. That very morning, he was still some distance from the ferry when he encountered several Sonorans who warned him to flee for his life. Not understanding Spanish, he continued on until halted by a Sonoran woman who pulled him from his horse. In a move that Anderson perceived as erotic, she hustled him into some bushes and urged him to shed his clothes. As she handed him some Mexican garb to cover himself, he understood: the woman was only interested in saving his life.

His story was troubling. But Anderson had also learned there was another ferry at Algodones. With a trackless desert on all sides, the party had no choice but to proceed down the Gila to the feared ferry crossing. Two days later, as they arrived at the mouth of the Gila, they noted a six-foot high mound of dirt on the bank before them. Across the Colorado, to their right, the Glanton Ferry lay desolate. Turning south, the Americans followed the Colorado through the incredibly dense mesquite and desert willow to Algodones.

That evening 10 Yumas appeared unarmed. The Americans asked if they could speak to their chief. Shortly after, Chief How Honni, or Jumping Fox, entered camp. After ceremoniously accepting some shirts, handkerchiefs, jewelry and pinole from the Americans, he seated himself and began explaining the lifeless scene they had witnessed up river.

With the departure of General Anderson, the Yuma had begun operating their ferry. It wasn’t long before almost all the Sonorans were using the Algodones crossing. The Glanton men, most particularly Glanton himself, were furious. Their fury was worsened when one of their number, an Irishman named Callahan, was found lying in the shallows of the river, dead of a bullet wound and robbed of his coins. It was then that How Honni decided to soothe matters by having a council with Glanton. But when he arrived at the ferry master’s stick hut, the occupant cursed him and swore that for every Sonoran ferried across the Colorado, one Yuma Indian would be shot.

How Honni then volunteered to leave the business of ferrying the men and baggage to the Americans; the Yuma would ferry the animals only. Glanton responded by picking up a stick, cracking it over the Chief’s head and thrusting him out of his hut.

How Honni returned to Algondones and held a council. At the end, it was decided that they would kill all the Americans at Glanton’s Ferry. But the following day, the Yuma learned that Glanton had left for San Diego to purchase more whiskey and provisions. As he was the main target of their anger, they decided to wait for his return.

A week and a half later, Glanton arrived with a fresh store of whiskey and flour. The chief immediately went to the camp where Glanton and the others were standing about drinking whiskey. More subdued than usual, Glanton gave How Honni a drink and handed him a plate of dinner before telling him that he could not operate his ferry. The chief finished dinner, thanked Glanton, and took a boat across the river to the Arizona side. There he entered the brush to hold a final war council.

Meanwhile, Glanton and the other four Americans went to sleep—Glanton in his hut, Lincoln in his tent and the other three inside the cook house. All were positioned about 100 yards from the river bank. The five went to sleep despite the abnormally large number of Indians about camp. Across the river, six more Americans were preparing to dock the ferry.

As the Americans aboard the ferry neared the shore, the chief suddenly emerged from the brush, strode atop the mound above them, hoisted aloft a staff with a scarf attached, and began waving it back and forth. At the signal, dozens of Yuma on shore surged aboard the ferry. The Americans tried to relaunch themselves but were overwhelmed by the clubs and spears. Killed and tossed into the river without ceremony were John Gunn and Henderson Smith, both formerly of Missouri, Thomas Watson of Pennsylvania, James Miller of New Jersey and Thomas Harlin of Texas. The name of the sixth American is not known.

Across the river, a sub-chief on the California side entered Dr. Lincoln’s tent. Next to Lincoln, a Mexican woman sat sewing. The chief stepped passed her and brought a rock down on Lincoln’s head. The Doctor struggled to his feet half conscious. As he did he was struck on the head with a war club, collapsed and died.

In the adjacent hut another sub-chief struck Glanton on the head with a rock as he lay sleeping. The blow glanced off; as Glanton too struggled to his feet, he was killed by a blow from a hatchet. Slain in the cook house were John Jackson, a Negro formerly of New York, Prewitt formerly of Texas, and Dorsey of Missouri.

Meanwhile, the three other partners at the ferry, Joseph Anderson (not to be confused with the other Andersons), Marcus Webster and William Carr were 300 yards up the California bank cutting trees for poles. Unaware of the mounting carnage below, they became suspicious after some 15 Indians appeared in the clearing and told them they had come to help. When one of the braves applied a hatchet much too close to Carr’s head for comfort, Anderson pulled his pistol and waved him off. At this, the Yuma hurriedly left.

The three were so aroused they began crashing through the brush after them. Hearing the clamorous shrieks below, they charged into the clearing and made for camp, firing their revolvers, scattering some 40 Yuma. Over at the structures, only Carr took time to peer into Glanton’s hut for a look at his lifeless body. Realizing they could neither remain in camp or find refuge in the nearby timber, in an act of desperation the three rushed toward the river where the Yuma were clustered, guns blazing. The Yuma, who greatly feared American marksmanship, fled in all directions. At the shore Anderson, Carr and Webster unhitched a small skiff and launched themselves.

Out on the river the current swept Anderson, Carr and Webster downstream as Indians on both shores began showering them with arrows. One of the missiles struck Carr in the Achilles tendon. As they continued downstream, the Yuma, most on foot, a few on horseback, pursued them, firing an occasional gun. While one American paddled, the other two squatted and fired away. Their fire was quite accurate, killing two Indians and wounding many more. In the entire fight, upward of 10 Yuma are thought to have been killed.

The gauntlet at long last run, some miles below Algodones, the three abandoned the skiff on the Arizona side. Despite Carr’s wound, they quietly made their way inland. As night closed in, amidst the mesquite and cactus they rested and pondered their slim chances of survival. At moonrise they crept back to the river bank only to find the Indians had taken their skiff.

The three turned and headed down river. On the morning of April 24, they began building a raft. After finishing it, they paddled across the river and ascended a thicket-shrouded creek. As the brush turned to open desert, they were startled by the sight of 20 Yuma Indians on the bank. The three drew their Colt six-shooters and pointed them. In response, all but one man and a boy scrambled up the bank. The two, aware of the limited range of revolvers, remained where they were, shouting such abuse in Spanish as, “You had better get away, for we intend to kill you.”

Eventually, the man and boy departed, and Anderson, Carr and Webster brought the raft in and slogged ashore. They abandoned the vessel and struck northward hoping to find the trail leading to Algodones. As they quietly pressed ahead in the moonlight, by the wayside, they could see Indian huts inside of which their mortal enemies slept. Carr, limping because of his wound, in a vengeful mood, wanted to kill the occupants. But with just 11 loads between them, Anderson and Webster voted him down.

On the morning of April 27, the three approached what was left of Glanton’s Ferry itself. They quickly mingled with a camp of early rising Sonorans who had crossed the night before. It was then they learned the ultimate fate of their former partners.

After the Americans on the east side had been killed and tossed into the Colorado, across the river the bodies of Lincoln and Glanton were thrown in a heap. Brush was piled on top. While Lincoln’s dog was tied to his body, two other camp dogs were tied to Glanton. The brush and the nearby huts including the cook house, with the bodies of Jackson, Prewitt and Dorsey inside, were set afire. The dogs were burned alive and the huts and clothing of the men reduced to ashes. But the funeral pyres did not generate enough heat to destroy the bodies and, like their brethren across the way, they were tossed into the river.

By now the Sonorans on the east side had been joined by the 14 Americans who had just come up from Algodones. No less than 150 migrants were now camped on both sides of the Colorado. The Americans on the east bank, in their talk with How Honni, had learned that in three short months Lincoln and Glanton had amassed some $80,000 in tolls and the sale of supplies. In addition to three sacks of silver coins, they had a sack of gold dust one foot in diameter. A month later, inside the Los Angeles courtroom of Alcalde Abel Stearns, the sums would draw much unfavorable com-ment. But Anderson, Carr and Webster insisted that the ferry’s remoteness and high cost of operation warranted the amount.

How Honni too had returned to the main crossing. Feeling he had justified the killing of Glanton and his men to the Anderson Party, he decided to let them pass. On April 26, a total of 164 people were ferried across the river. But the Amer-icans, before reaching the California side, were forced to land on an island, jammed with Yuma men, women and children. There, while the men remained grimly im-passive, the women and children heaped abuse on them, approaching within three feet and shouting, “God damn your souls, Americans!”

In addition to this gauntlet, the Americans were forced to pay a double toll before landing. Even then they were not out of danger. One of the Yuma sub-chiefs approached Senior Montenegro, leader of the Sonorans, and warned him to decamp immediately as all the Americans were about to be killed. Montenegro reacted by permitting the Americans to mingle with his party. The Yumas did not attack.

The next day, more crossings followed. That evening, Senior Montenegro, by all accounts a brave and selfless leader, was among the last to leave the ferry and was captured by several Yuma Indians. Fortunately, another Sonoran came up the trail from behind and, with gun drawn, forced the Yuma back. But more braves descended on them and refused to allow Montenegro to pass until he’d given them a bag of pinole and opened his trunk. He obliged, and the Yuma helped themselves. Only by nightfall did Montenegro catch up with the main party, most of whom were not aware he had been detained. The mixed party crossed the desert to San Diego. Despite repeated harassment by the Yuma, they did not suffer any casualties.

Shortly after their arrival, California Governor Peter Burnett learned of the ferry disaster and dispatched General Joseph C. Moorehead and 40 men to the Colorado River. As they approached, the Yuma fled northward, vanishing into the wilderness of rock, sand, water, brush and heat. Moorehead remained encamped at Glanton’s defunct ferry for some months before being recalled. Periodic attacks on Americans using the Colorado-Gila crossing continued for some years, and it wasn’t until the Civil War that the Yuma were completely subdued.

Chris Burchfield, historian and writer, lives in Corning, California. This is his first article for True West.