While a prisoner at the castle of Perote, Walker was put to work raising a flagpole. At the bottom of the hole, Walker placed a Yankee dime, vowing to someday come back and retrieve it, at the same time exacting revenge on his Mexican captors. In the summer of 1847, when Walker’s mounted riflemen returned and routed Santa Anna’s guerillas, the young captain kept his promise and got his dime back.

IN SEPTEMBER 1842, after first stepping foot in Galveston, Texas, 25-year-old Samuel Walker joined Jesse Billingsley’s Company of Mounted Volunteers. A hastily-recruited Bastrop County militia command, Billingsley’s Volunteers went to the defense of San Antonio, under attack by a force of some 1,000 Mexican troops under the command of General Adrian Woll.

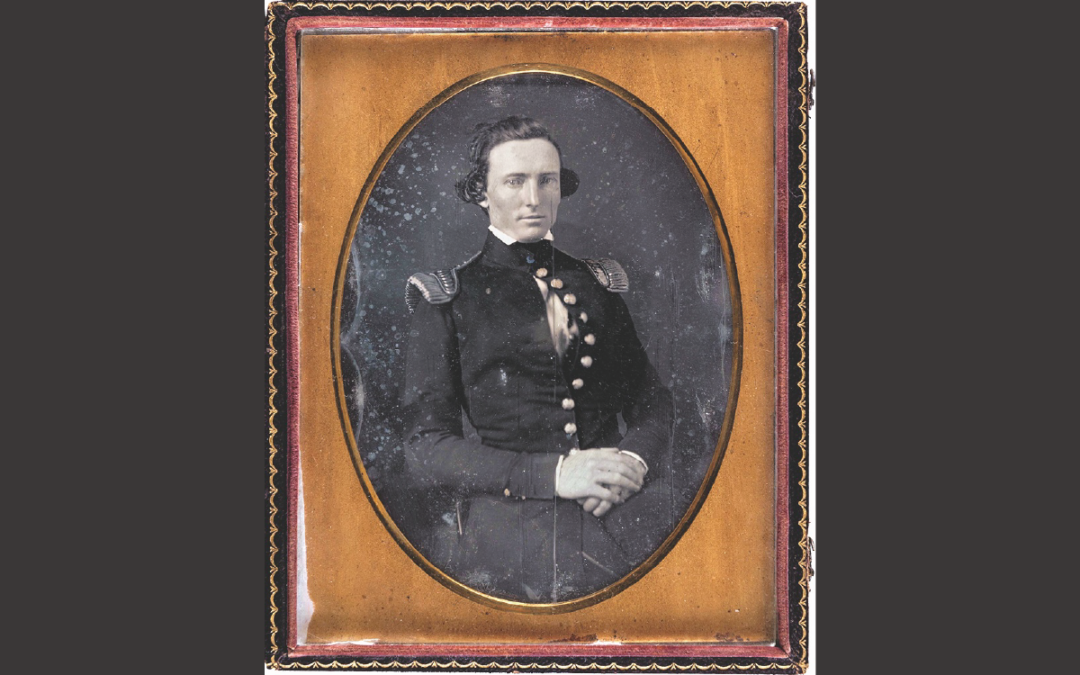

Courtesy Heritage Auctions

CAPTAIN SAMUEL HAMILTON WALKER, TEXAS MOUNTED RIFLES

Born: February 24, 1817, Prince Georges County, Maryland. Fifth of seven children.

Parents: Nathan and Elizabeth Walker.

Former Occupation: Carpenter, railroad worker.

Military Record: Washington City Volunteers (1817-1836). Organized for engagement in the Seminole and Creek Indian Wars in Florida and Alabama.

Arrival in Texas: January 1842.

Jesse Billingsley had previously commanded Company B of Colonel Edward Burleson’s regiment, and was wounded at the celebrated Battle of San Jacinto. But Billingsley’s Volunteers was not the only Texas militia group racing toward San Antonio. On September 18, some 200 volunteers and a small band of Texas Rangers engaged elements of Woll’s army at the Battle of Saldado Creek. Although Samuel Walker missed the fight, the Texas forces celebrated a small victory. That, along with the approach of more Texas militia, forced General Woll to retreat from San Antonio, across the Rio Grande.

Two months later, in November 1842, Brigadier General Alexander Somervell, operating under broad discretionary powers from Governor Sam Houston, organized his First Brigade of Texas Militia to undertake a punitive expedition against Mexican commands in South Texas. Muster rolls indicate S.H. Walker was the first of 77 privates who enlisted in Captain Ewen Cameron’s Company A. The force would eventually consist of some 750 officers and men. On November 13, Somervell sent the first elements of the Texas army out of San Antonio to the Medina River, where they camped for two weeks until reinforcements arrived.

THE MIER EXPEDITION

As the Somervell Expedition moved across South Texas, the group captured Laredo and moved past Guerrero, then downriver toward the town of Mier. During the march, Somervell experienced many problems, the most serious involved a general lack of discipline among the troops. Many soldiers refused to follow orders, as a result, the safety of the army was in question. When reports of larger concentrations of the Mexican army were approaching from the south, Somervell elected to take the Texas army back to San Antonio.

Many of the officers agreed that an invasion of Mexico was ill advised and marched back to San Antonio as ordered. But almost 300 men, including Private Sam Walker, elected to invade Mexico under the command of Colonel William S. Fisher. The invasion would take place at Mier.

A few days later, Walker and Patrick H. Lusk were captured while on patrol. During the Battle of Mier, which finally took place on December 25, 1842, 10 of the 261 Texans who crossed the river were killed. The remainder were captured and began a torturous ordeal at the hands of the Mexicans. Within a few days, Mexican authorities denied them status as prisoners of war. As a result, the Texans were forced to march to a prison near Mexico City in chains. Brutal treatment by the guards, poor rations, and a lack of medical treatment was only the beginning of their nightmare.

During the almost two years of captivity, over a hundred of the Texans attempted escape. Only 26 were successful, including Samuel Walker. Eighty-two of the prisoners were killed during captivity. Those caught escaping were taught powerful lessons. At one point, a group of Texans at Hacienda Salado were forced to pick from a jar of beans. A white bean meant survival; those who drew a black bean met their death before a firing squad. Seventeen black beans were dealt. Seventeen Rangers fell. The remaining 136 Texans were finally released on September 16, 1844, and ordered to walk back to Texas.

Samuel Walker spent seven months in captivity, avoided the firing squad when he drew a white bean, and escaped on July 30, 1843. Walker and his two companions finally reached Tampico two weeks later. Walker arrived in New Orleans in September 1843, and booked passage to Galveston. He was back on Texas soil by year’s end.

THE PRIVATE AND THE PATERSON

After the defeat at Mier and other failed military ventures, substantial funding for Texas troops was curtailed. As a result, the defense of Texas against Indians and Mexicans fell largely to the various militias and to small groups of Texas Rangers. About the time Sam Walker was arriving in New Orleans, even the Rangers had been reduced to a single company commanded by Captain John Coffee Hays. The command consisted of only 25 men. Before Walker could return to Texas, Hays’ company was disbanded for lack of funds.

On January 23, 1844, the Republic’s Eighth Congress passed an appropriations bill creating an new Ranger command. Captain John Hays was to lead the group, initially ordered to patrol the “Western and South-Western Frontier.” The force would consist of some forty enlisted men. Funding prevented enlistment of more than two to four months.

During his visit to the capitol at Washington-on-the-Brazos, John Hays experienced what some call “Texas Luck.” Hays was informed about some unused revolvers, originally purchased for the Texas navy. A few had been issued, but the rest were packed in a government warehouse. These revolvers were among the first Paterson Colts, a five-shot, .36 caliber weapon made by Sam Colt in New Jersey.

Colt’s new revolvers were unwanted by everyone but the Texas navy, who got a great bargain when they purchased over 100 of the guns in 1839. After some use, even the Texas navy was reluctant to issue such a delicate weapon. The Paterson lacked a trigger guard; the trigger dropped from the frame when the weapon was cocked, making it hazardous to carry and fire effectively. Captain Hays had a better opinion of the gun. When he returned to organize his Texas Rangers in 1844, he brought the Colt Patersons with him.

Lieutenant Ben McCulloch had already begun enlisting Rangers when Hays arrived with the weapons. Private Sam Walker, anxious to exact revenge on Mexico, joined the Texas Rangers in February 1844.

As long as the state provided the funds, a Ranger company could be raised to serve and patrol the frontier. In early June 1844, Captain Hays led a

fifteen man patrol, which included Sam Walker, north of San Antonio to confirm stories of raiding Indians in the area. The patrol found signs of Indians, but none were encountered until the Rangers turned south. Someplace between the Pedernales and Guadalupe river the Rangers detected a large group of Comanche warriors moving in their direction.

Near one of the numerous spring-fed creeks in the area, called Walker’s Creek, the Comanches attempted to bait the Rangers. Hays, whose men were now armed with the five-shot Colt revolvers, decided to find out just what the pistol was capable of in actual combat. With only 15 men, Hays led an attack against an estimated 60 to 70 Comanches. Hays later wrote that, “The fight, which was a moving one, continued to the distance of about thirteen miles—being desperately contested by both parties.” One Ranger was killed during the fight, and four wounded, with Comanche casualties estimated at fifty killed or wounded, including Chief Yellow Wolf.

Hays, in his official reports, credited the “five-shot repeating pistols” with the victory. “Had it not been for them, I doubt what the consequences would have been. I cannot recommend these arms too highly.” During the fight, Sam Walker and R.A. Gillespie were separated from their command, and both suffered wounds form an Indian lance. According to Hays’ report, both Rangers were “wounded badly.” Returning to San Antonio, Walker was left in the care of a Mrs. W.H. Jacques, who nursed him back into fighting shape.

True West Archives

Walker’s unit was christened the Texas Mounted Rangers. Utilizing former Texas Rangers, it was not a unit that Mexican soldiers would want to meet in battle.

THE TEXAS MOUNTED RANGERS

By the end of 1844, the Rangers were again short of funding. In February 1845, new appropriations were voted through and the ranger command expanded to include smaller companies raised in Travis, Bexar, Milam, Roberts, Goliad, and Refugio counties. Captain Hays resigned on August 12 and was succeeded by R.A. Gillespie. Captain Gillespie and his forty-three man company, including Private Sam Walker, were discharged on September 28, 1845, some three months after Texas became a state.

A few days before discharge, Gillespie began forming a company of mounted volunteers, named the Texas Mounted Rangers. The group was made up of San Antonio volunteers, mustered into federal service on September 28. Sam Walker, now 28, eagerly joined, again as a private.

As the end of Samuel Walker’s term of enlistment in the Texas Mounted Rangers approached, he finally closed the book on being a private soldier. Walker arranged a meeting with General Zachary Taylor, who was quartered at Corpus Christi. Walker, hungry for action, offered his services to the United States Army, which was preparing to go to war with Mexico.

Samuel Walker’s chances of joining Taylor’s army were good. He had served in Florida and Alabama; he had known Lieutenant George Meade, now under Taylor’s command; and most importantly, he knew the approaching battlegrounds well from his service and escape during the Mier Expedition.

Sam Walker was accepted on April 21, 1846, and was authorized to raise the first company of scouts for Zachary Taylor’s army. With a total complement of 93 officers and men, many of whom were veterans of the Mier and Somervell expeditions, Captain Samuel Walker’s unit was christened the Texas Mounted Rangers. Utilizing former Texas Rangers and veterans of the Mier Expedition, it was not a unit that Mexican soldiers would want to meet in battle.

During the first months of hostilities in the Mexican War, Samuel Walker became a national hero and a living legend. After his reported death and a daring mission to Fort Brown behind enemy lines in 1846, the city of New Orleans presented Walker with a “magnificent horse” named Tornado.

After American victories at Palo Alto and Resaca de Palma in early May 1846, the Mexican army retreated across the Rio Grande. The Mexicans were handed more defeat on the west coast and in New Mexico. Although the U.S. expected the Mexican army to beg for mercy, the war continued. As a result, the Army broadened efforts to invade Mexico. While troops were moved into South Texas, three mounted scout regiments were raised. Colonel John Hays, George T. Wood, and William C. Young commanded the units. Many of Walker’s former scouts were absorbed into service.

On June 24, Samuel Walker was elected a brevet lieutenant colonel by the troops of the First Regiment, Texas Mounted Riflemen, and was second in command to John Hays. He joined the group when his own term of enlistment ended on July 16. Six days later, Walker was elected lieutenant colonel in the Texas volunteer command; he also accepted a regular army appointment as a captain in the First U.S. Mounted Rifles. His appointment was delayed until the First Regiment, Texas Mounted Riflemen was mustered out of federal service on October 2, 1846.

THE BIG GUN

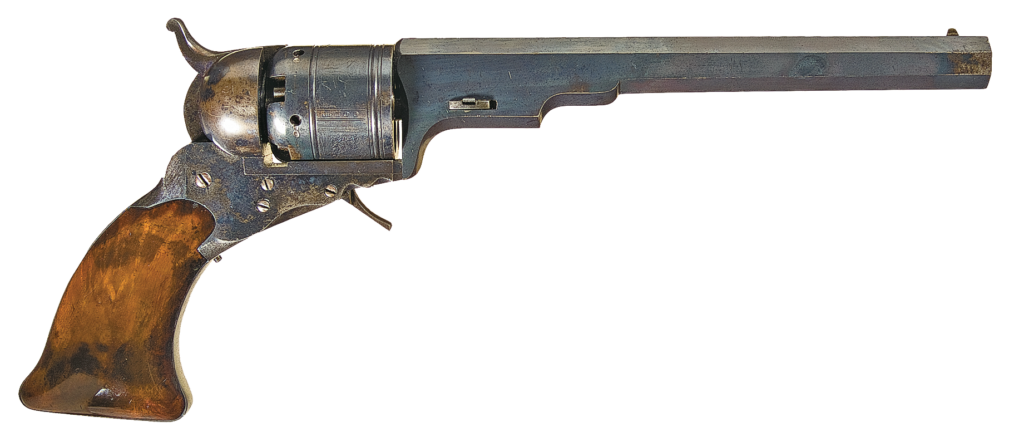

After Walker’s enlistment expired, he visited the northeastern states to personally recruit men for Company C, U.S. Mounted Rifles. Because of Walker’s notoriety, Samuel Colt wrote to him while the former Ranger was in New York. The two men met in late November 1846. Walker was interested in acquiring weapons for his new command, while Colt, whose company had failed, wanted to convince the Army to buy his guns.

Walker and Colt entered into an agreement in January 1847, which satisfied both their desires. Walker suggested valuable alterations to the original revolvers, which he came to know well as a Ranger. Within a month, Samuel Walker had been given authority by the government to purchase 220 of the new revolvers and proceeded to Newport Barracks to recruit and train his new command. In April 1847, Walker and Company C of the Mounted Rifles shipped out for Vera Cruz, Mexico, without receiving their 1847 Army Pistols, better known as the “Walker Colts.” Finally, on June 26, the Army took delivery of the guns, which were shipped to Vera Cruz to await Walker’s men.

The gun was a masterpiece of destruction. Each weapon held six shots, and came with a custom tool and reloading kit. Fitting Walker’s specifications, and lessons learned in the Rangers, the gun was large enough and strong enough to withstand close-quarters combat. The weight alone enabled the user to pummel their opponent to death when the chambers were spent. Unfortunately, the Walker Colts didn’t reach the Mounted Rifles in time.

THE END OF THE MYTH

Captain Samuel Walker was now fighting in the army of Winfield Scott, in a much more savage and destructive war than Zachary Taylor’s South Texas campaign. General Scott was fighting his way uphill from Vera Cruz, toward Mexico City. It was a tough, bloody war.

Captain Walker’s command, consisting of some 250 men, took the chore of keeping the supply roads open and forcing Santa Anna’s guerrillas to run for their lives. They were successful on both fronts, striking fear with hit-and-run tactics and declaring to “take no prisoners.”

On October 9, 1847, Company C still had not received their Walker Colts, but Sam Walker received a pair of presentation pistols from Sam Colt himself. Four days later, during action against guerrillas in Huamantla, Mexico, Captain Walker was shot and killed in action. Some accounts claimed he was lanced to death, but nevertheless, a valiant warrior and a legend among the Texas Rangers had fallen. Sam Walker’s body was brought back to the United States and buried in San Antonio.

Samuel Walker spent his entire adult life pursuing one war after another. He went to war voluntarily in Alabama, Florida, and several times in Texas and Mexico. He finished his life on the battlefield, attacking Mexican troops directly commanded by Texas’ greatest enemy, General Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. It is doubtful Sam Walker would have wanted it any other way.

Allen G. Hatley, a retired Texas lawman, is the author of Texas Constables. This is his second article for True West.