Surprising new evidence has surfaced in the Wyatt Earp claim that he killed Curly Bill. Wells Fargo historian, Robert J. Chandler, accidentally found an entry in the original Cash Books that points to a stunning possibility.

Surprising new evidence has surfaced in the Wyatt Earp claim that he killed Curly Bill. Wells Fargo historian, Robert J. Chandler, accidentally found an entry in the original Cash Books that points to a stunning possibility.

The entry seems to indicate that Wells Fargo paid blood money to Wyatt Earp for killing Frank Stilwell and Curly Bill Brocious. Robert J. Chandler recounts the find:

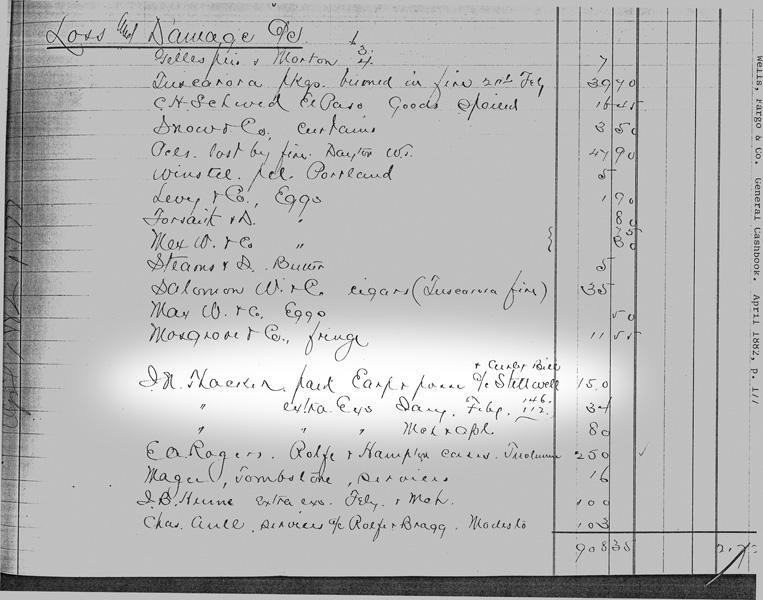

“During my first project with the history department of Wells Fargo Bank in September 1978, I was the first to heft the large, heavy, unwieldy Cash Books, which the new bank holding company, Wells Fargo & Company, bought back from American Express in 1969 along with all rights under the 1866 Colorado charter.

“Many years later, having to prepare a stagecoach parade release for New Mexico, I searched my notes for Wells Fargo’s entry into that territory. I surprised myself with an Earp entry for April 1882 several months later than all previous ones, which I found buried and forgotten in my 21-year-old notes: ‘J.N. Thacker paid Earp & posse a/c Stillwell [sic] & Curly Bill $150.’

“Having enjoyed Casey Tefertiller’s 1997 Wyatt Earp, I realized that the involvement of detective John N. Thacker made it of more than passing interest, and reinforced Tefertiller’s conclusions about Wells Fargo’s support for the Earps.”

Earp historian, Timothy Fattig, of Tombstone, Arizona, responded to our inquiry about the importance of this find, saying, “This validates that Wells Fargo did a separate investigation [by John Thacker]. The company would not have paid Wyatt Earp a cent if they did not have satisfactory proof of Curly Bill’s death.”

Jeff Morey, another noted Earp historian (and technical advisor on the movie Tombstone) had this to say: “I found the Wells Fargo cash records most intriguing. It isn’t completely clear, however, what exactly the ‘Earp posse’ was being paid for relative to Stilwell and Curly Bill. What does the notation ‘a/c’ stand for? For blood or reward money, $150 seems rather small. It seems possible that the ‘Earp Posse’s’ expenses while in pursuit of Stilwell and Curly Bill were being paid. Yet, that begs the question as to why the pursuit of Morgan’s murderers should specifically make mention of only Curly Bill and Stilwell. If expenses were simply being paid, the mention of these two would be totally extraneous and misleading. Three things are made clear: 1) The Earps worked very closely with Wells Fargo and enjoyed the complete trust of the company; 2) Wells Fargo viewed the ‘vendetta ride’ as legitimate posse work.; and, 3) Wells Fargo was satisfied that Earp had indeed dispatched Curly Bill. The linking of Curly Bill and Stilwell would seem to be their common deceased nature. Of course, there are those who will say this doesn’t prove that Earp did, in fact, kill Curly Bill. All it shows is that Wells Fargo thought Earp killed Curly Bill. The counter to such an argument would be to point out that Wells Fargo wasn’t prone to pass out funds while any lingering doubts remained.”

On the opposite side of the argument, Steve Gatto, author of The Real Wyatt Earp, 2000, stated, “It doesn’t add up—it’s too low a payment for a killing. Of course, it’s complete speculation on my part, but it sounds more like it would be an expense reimbursement for the September ’81 Stilwell/Spence robbery. Either by Earp’s allegation or rumor, the bookkeeper may have mistakenly connected Curly Bill to the March robbery. Wyatt Earp, later, in both unpublished works and Stuart Lake’s book, alleges that Curly Bill had a connection to the robbery. So, I think Wells Fargo is just paying expenses on the account.” March, Murders, and a Motive

Wells Fargo messenger Morgan Earp, was murdered on March 18, 1882. The Earps counter attacked, felling Stilwell on March 21, and Curly Bill Brocious (Wyatt’s claim) on March 24, 1882.

The following quote in the March 23, 1882, San Francisco Examiner indicates why a reputable bank might be motivated to take the law into their own hands. Describing the cowboys, a group of about 75, Wells Fargo spokesman said that a portion, “under the leadership of Ike Clanton,” were “cattle thieves, and for a change will occasionally rob a stage.” This bad situation arose, Wells Fargo officials explained to the San Francisco journalists, in part due to the more than neutralization of Sheriff John Behan: “In fact, it is stated,” being more coy than necessary, “that a leading official stands in with them whenever occasion arises.”

Whatever we finally decide about the entry, we can conclude that new discoveries change our view of history—and for that reason alone, every tidbit that emerges is worth contemplating. Thanks to Robert J. Chandler and Wells Fargo, who contributed this intriguing piece of evidence, we may have new insight; or, it may lead us to a conclusion unforeseen. For questions or comments, Robert Chandler may be contacted by e-mail at chandler@WellsFargo.com. And, for any of you who may know what “a/c” means, we’d like to hear from you at truewestmagazine.com.

Robert J. Chandler is a freelance writer and has worked with Wells Fargo Bank’s history department for 23 years. This is his first article for True West.

Photo Gallery

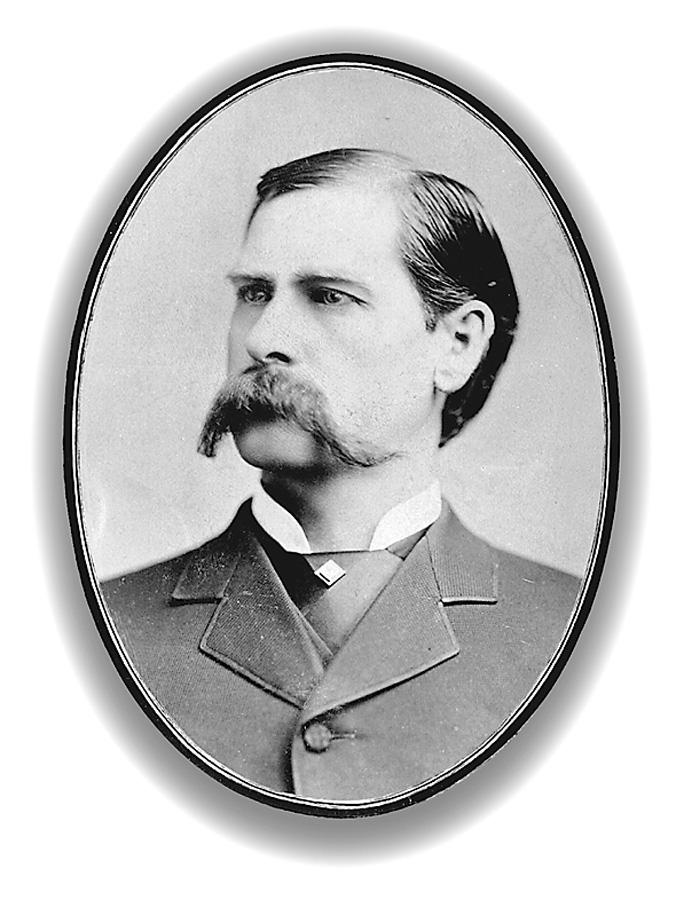

– Courtesy of Craig Fouts –

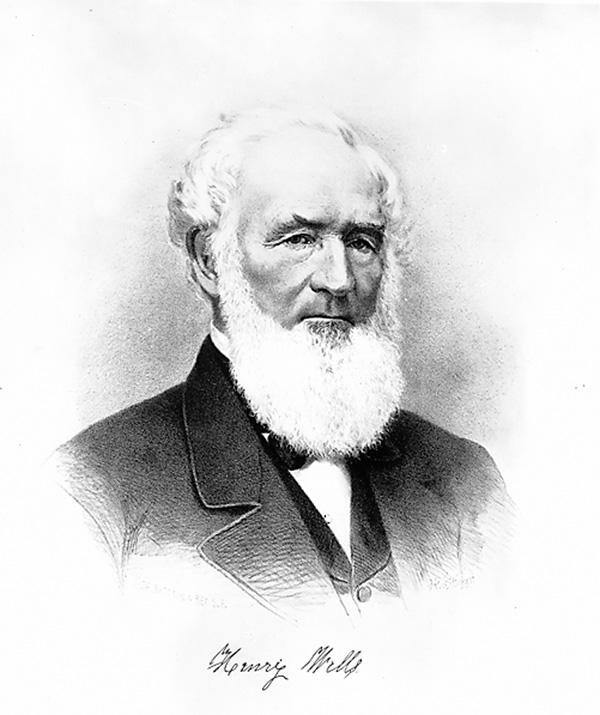

– True West archives –

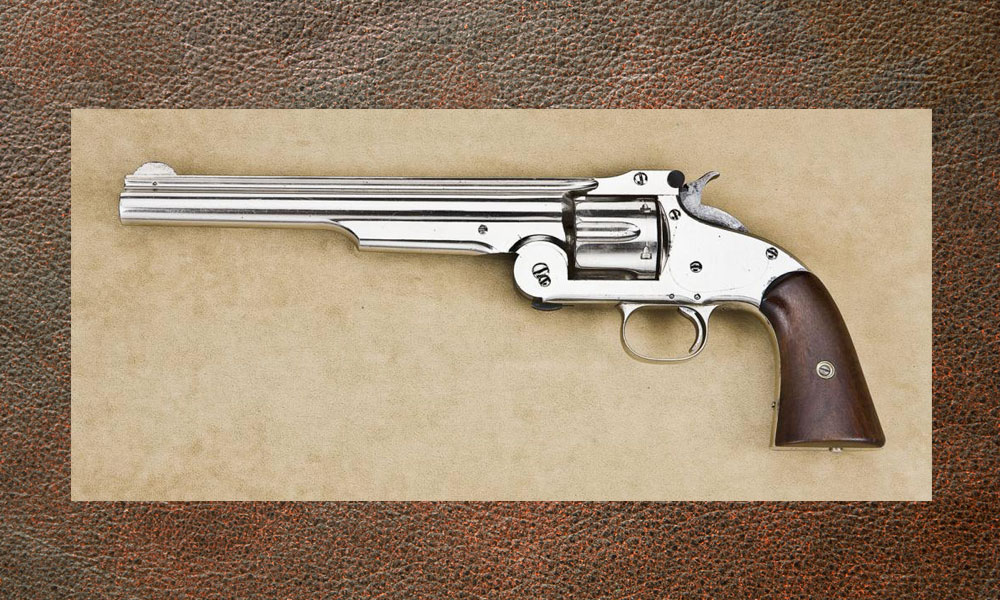

– Courtesy of Wells Fargo, History Department –

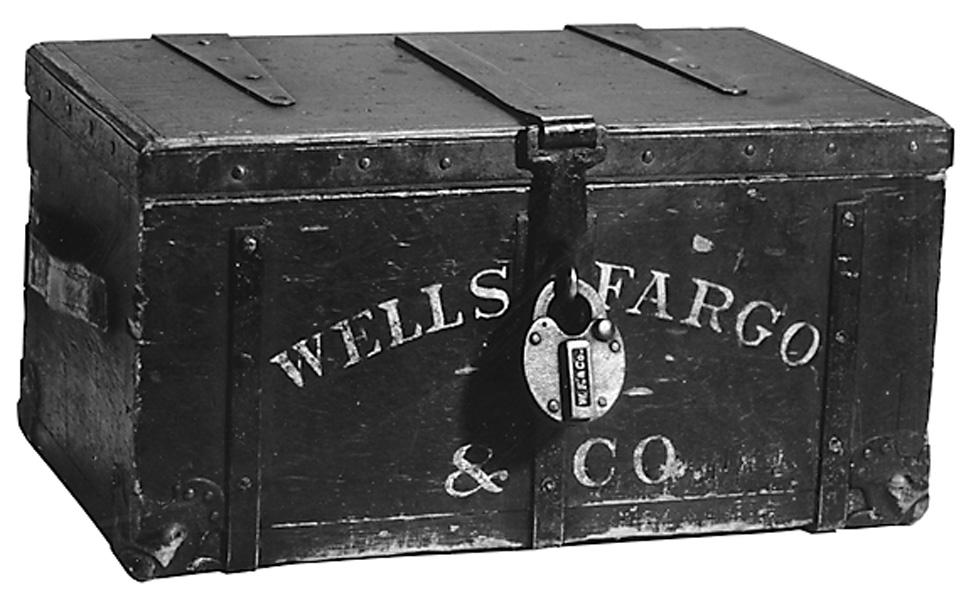

– Courtesy of Wells Fargo, History Department –

– True West archives –