Stinking rich was Ho-Ta-Moie, which means rolling or roaring thunder. But he will forever be remembered by the tribe as the man who returned from the grave.

John was born around 1863 and moved with the Osage Tribe to their new reservation in 1872. He was a member of the Big Hill Band, which set up camp at the village known as Grayhorse on the Osage Reservation. Due to some unknown misunderstanding with his relatives, John moved to Pawhuska, the capitol of the Osage Nation, in the 1890s and remained there the rest of his life.

The Osages retained the mineral rights to their one and a half-million acre reserve, providing a financial bonanza when vast deposits of oil were discovered in the early 1900s. All tribal members were allotted headrights and received royalties on all oil revenue. By the 1920s, the 2,229 Osage were the wealthiest people per capita on the face of the earth.

John received a headright and soon became a wealthy man. To many Osage, the windfall enabled the building of grand homes and the purchase of fancy new automobiles. Stories are still retold of the Osage abandoning new cars at the side of the road that were out of gas or had some minor malfunction, only to return to town and buy a new car as a replacement.

But big homes and new automobiles held little interest for John. He adhered to the traditional teachings of his grandfathers. Money could never change his philosophy toward life. John felt a deep kinship with the outdoors and worshiped the Great Spirit, Wah-Kon-Tah, through his daily communion with nature.

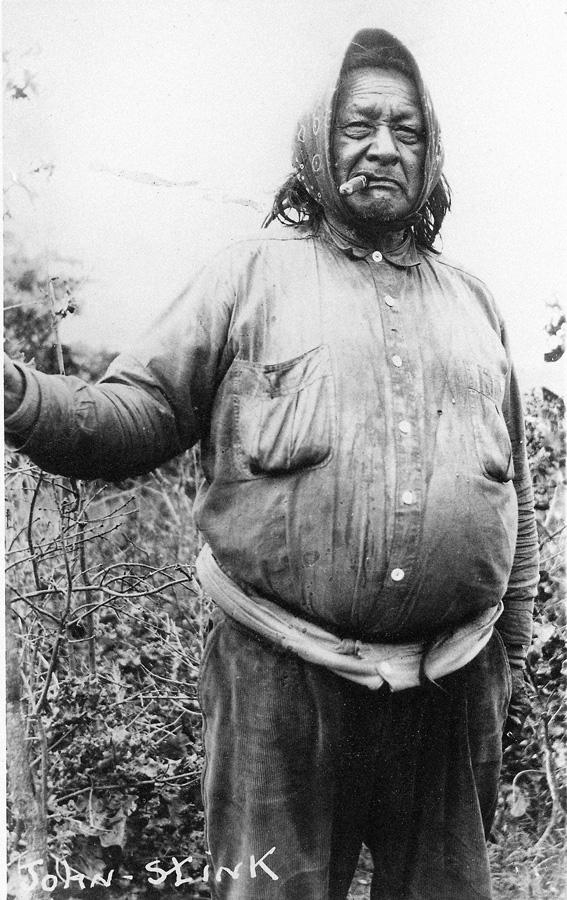

John hunted in the hills around Pawhuska in the company of his faithful dogs. He visited Pawhuska frequently, becoming a popular sight on the streets of town. John was a large man, standing six feet tall. He adopted the white man’s dress with the exception of a scarf that he wore on his head and the blanket that he draped over his shoulders. A cigar clenched between his teeth completed the picture.

Like many Osage, John had a guardian appointed by the Osage Agency to supervise the wealth flowing in from the oil royalties. Unfortunately, for many Osage, this well-intentioned program to protect the Indian had the opposite effect. Numerous unscrupulous whites flocked to Osage country, intent on cheating the Indians of their fortunes.

John’s guardian owned a store in Pawhuska, where John liked to visit. One of his favorite pastimes was to sit on a bench in front of the store and cut up beefsteaks to feed his dogs. Consequently, he never lacked for canine companionship. While visiting in town, he would usually sleep in the streets, preferring it to indoor accommodations.

Tragedy struck for John when police shot two of his dogs during a rabies outbreak in Pawhuska. The loss of two of his beloved pets enraged and saddened John. He decided to leave Pawhuska for good, only once returning to town before he died.

He established his first permanent camp near the old St. Louis Indian Girls School just southwest of Pawhuska. It was while living here that John experienced the famous episode which resulted in his return from the grave. Several versions exist concerning how John “died.”

One story claims that a smallpox epidemic struck Pawhuska and John became ill, worsened, lapsed into a coma and was pronounced dead by the medicine man. John was then prepared for burial and placed in a shallow grave in the sitting position. Stones were then piled around him with his face left uncovered so that he could find the afterworld. Miraculously, he awoke from the coma and climbed out of the rock grave, only to find himself rejected and shunned by his tribe as a ghost.

Another tale is identical to the previous story with the exception that scrofula, a type of tuber-culosis, struck John down instead of smallpox. He was buried in a rock sepulcher after cere-monial burial rites, only to emerge from his coma to the surprise and con-sternation of the tribe.

One version tells of John becoming intoxicated and passing out in some snow drifts. When he was discovered some time later he was believed to be frozen to death. After he was interred in his stony grave he thawed out and returned to the land of the living.

The most plausible sounding story tells how John became caught in a blizzard and was forced to dig into a snow bank to seek shelter from the storm. When he was found partially buried in the snow, he was thought to be frozen to death. He was taken to the cellar of his guardian’s house to await burial. John then apparently recovered from a severe case of hypothermia and emerged from the cellar to the amazement of all. The press sensationalized the story of John’s “return from the dead,” with subsequent versions embellished in the retelling.

The multiple versions of John’s death and resurrection led some writers to assume that each version was a separate incident. Thus some writers have John being buried two or three times with full ceremonial rites, when in fact he was buried only once, when he died in 1938 at the age of 75.

John’s wealth was also greatly exaggerated in many of the stories. He was often falsely reported to be a millionaire. One of John’s guardians, Dr. C.W. Williams, reported that John “received more mash notes (proposals offering marriage) than a movie star.” Although John’s financial condition was excellent, with about $50,000 invested in real estate and regular royalty payments, he was far from a millionaire. He enjoyed donating money to worthy projects, like the $1,000 he gave to build the Osage American Legion Hut.

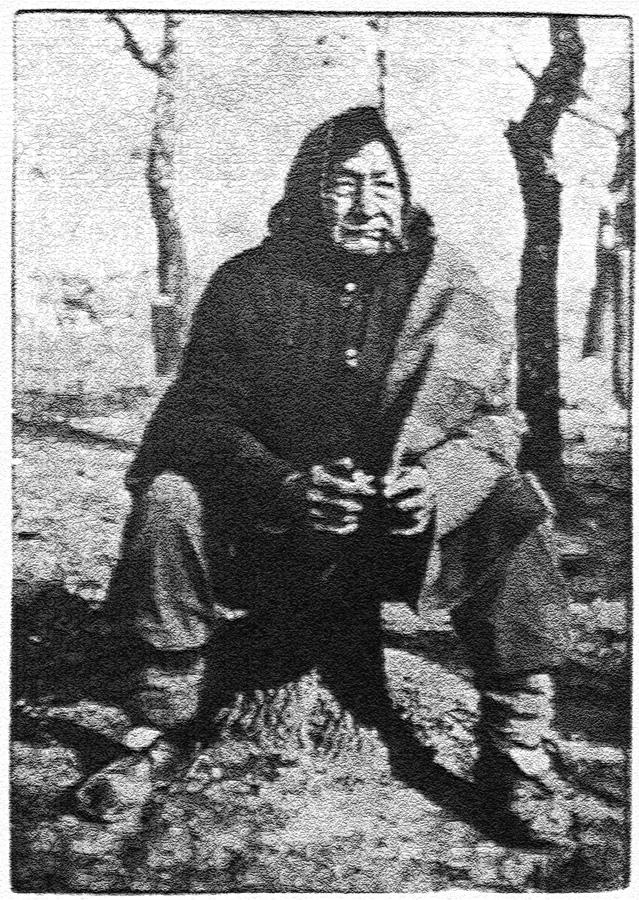

As the years passed, John spent most of his time hunting with his dogs in the Osage hills. He was persuaded to return to Pawhuska in 1906 when the Osage lands were allotted to tribal members. John’s allotment was located northwest of Pawhuska, near the country club. He lived in the open on his homestead, surrounded by his faithful dogs. John refused to live in a house for many years, but finally gave in and allowed the construction of a log cabin. The cabin had a sun porch, where he slept. The door to the porch was equipped with two-way hinges so that his dogs could come and go as they pleased.

Although John preferred a life of seclusion, he occasionally received visitors. Joe Shunkamolah was a friend who claimed that John never lost interest in people and often inquired about the Indian dances and the royalty payments. John was a fascinating and mysterious character to the small boys of Pawhuska.

A few boys, like Homer Herrington, even found the courage to go and visit John. Herrington recalls the uneasy feeling he had as he and a few other boys were greeted by many barking dogs. John called off the dogs and invited Herrington and his friends into his camp. They had no idea what to expect as John built a fire.

Once the blaze was going, John brewed a big pot of strong black coffee. He then gave each of the boys a cup of the coffee and a big cigar. The boys choked down the coffee and puffed on the cigars, later bragging to their friends about their visit to the legendary John Stink.

Another of John’s friends was a deaf-mute Osage named Pah-se-topah, who lived nearby. He and John would sit beneath the trees and converse for hours in sign language. Pah-se-topah and his wife would also help John by bringing him food when he was ill or when his guardian could not get supplies to him.

John observed the white man playing golf on the adjoining country club. Over the years, he acquired an impressive collection of lost golf balls. John was repeatedly reminded by his guardians that he was a wealthy man and could have practically anything he desired. He only requested that a high fence be built around his cabin to keep out unwanted visitors. The magazine stories about his return from the grave attracted a lot of bothersome curiosity seekers.

In 1938, John slipped on a rock and fell, breaking his leg. While recovering from the fracture, he became ill with pneumonia. He was confined to bed and became weaker as the pneumonia worsened. John died on September 16, 1938.

The funeral and burial were set for September 18. More than 1,000 people drove to the cabin where John’s body lay in state. Four of John’s dogs curled up beneath the casket, keeping vigil throughout the day.

Indian rites were performed by Osage leader John Abbott. Abbott eulogized John saying that he had lived a simple life, never doing harm to anyone. He continued by remarking that when a man had lived a long and good life, the road becomes clear to him and the traveling is good.

John lay in his coffin wrapped in an Indian blanket with his familiar scarf over his head. In one hand was placed a large black cigar, one of his few worldly pleasures. The other hand contained a rosary he had owned since he was young.

Abbott concluded the funeral oration at the cemetery at noon, the time when Osage legend holds that the gates of Heaven swing open. John was buried in a mausoleum, but many of his friends felt that John would not have approved, as he had always lived his life outdoors. Thus John Stink was finally entombed in the “rock grave.” Though John has left this world, the legend of the Osage who returned from the grave lives on.

J.D. Haines, M.D. Family practitioner, great-grandson of Wiley Haines and author of a forthcoming book entitled, Wiley Haines: Frontier U.S. Deputy Marshal, Eakin Press, has published over 100 articles, several appearing in the pages of True West.

Photo Gallery

– Author’s Collection –

– Author’s Collection –

– Author’s Collection –