Depending on who you believe, the Rangers in Texas began their existence in either 1823, only two years after Anglo-American colonists first settled there, or 1835 when the legislature created a body of fighting men known as the Texas Rangers. Their job was to protect the early settlers against marauders. Fighting was a risky adventure, and many a young man joined for no other reason.

Depending on who you believe, the Rangers in Texas began their existence in either 1823, only two years after Anglo-American colonists first settled there, or 1835 when the legislature created a body of fighting men known as the Texas Rangers. Their job was to protect the early settlers against marauders. Fighting was a risky adventure, and many a young man joined for no other reason.

New recruits were privates, and they were led by captains and lieutenants. Privates received $1.25 per day but had to supply their own horses, weapons and other equipment. They were expected to be ready to ride at all times with a good horse and 100 rounds of ammunition.

Sometimes Rangers fought Indians, but often they were no more than scouts or couriers for the regular army. After the fall of the Alamo (March 6, 1836), Rangers helped settlers flee and destroyed abandoned stores so Santa Anna’s army could not use them. They did not participate in the Battle of San Jacinto in which Sam Houston’s army defeated the superior Mexican force under Santa Anna, because they were working as escorts.

After Houston became president of the Republic of Texas in 1836, the Rangers seldom engaged Indians due to Houston’s preference for treating rather than fighting.

Under Houston’s successor, Mirabeau B. Lamar (1838-1841), however, the policy was reversed. Of the numerous pitched battles and minor engagements between Rangers and Indians, the most notable were the Council House Fight at San Antonio (March, 1840) and the Battle of Plum Creek (August 1840), both against the Comanches. By the end of Lamar’s term, the Rangers had weakened but not eradicated the most fearsome tribes in Texas. The Indian danger would remain a fact of Texas life for decades to come.

When Houston succeeded Lamar (1841-1844), he realized the need for protecting the frontier. Rangers were the least expensive and most efficient force to accomplish this purpose. Besides the threat of Indians, Mexico again became a serious problem for Texans. More Ranger companies were created, and a number of captains made names for themselves. John Coffee “Jack” Hays commanded 150 Rangers and successfully repelled the Mexican invasions of 1842. He also protected Texans from Indian attacks. Many Ranger traditions and the Texas Ranger mystique were created under Hays. The McCulloch brothers, Sam Walker and W.A.A. “Big Foot” Wallace became Texas Ranger icons after having apprenticed under Hays.

Up to now the Rangers were known only locally as a fighting force. The Mexican War, however, brought them national fame. Rangers fought valiantly at the decisive battles of Palo Alto Prairie and Resaca de la Palma in May 1846. They also became the “eyes and ears” of General Zachary Taylor. They led the American army to Monterrey and fought at Buena Vista. Under Hays and Walker, Rangers earned their reputation as lethal fighters, gaining them the nickname los diablos Tejanos. Their reputation of ruthlessness and brutality against Mexican minorities would stay with them until modern times.

Following the Mexican War the Rangers had no official function, thus few of their activities were recorded. Then in early 1858 John S. “Rip” Ford became senior captain and sent Rangers north to the Red River to subdue the hostile Comanches. In 1859 Ford ordered Rangers south to Brownsville where they had only limited success against the noted robber chieftain Juan N. Cortina, who would give Texans headaches through the 1870s by launching his raids from south of the Rio Grande.

With the onset of the Civil War, many Rangers enlisted in the Confederacy. The Eighth Texas Cavalry became known as Terry’s Texas Rangers, after its founder Benjamin F. Terry. He was never officially a Texas Ranger, however, nor did he purposely recruit Rangers. During Reconstruction (1865-1874), the Rangers were virtually non-existent, having been replaced by the U.S. Army and the Texas State Police, an unpopular organization created to reduce lawlessness.

Following the election of Governor Richard Coke in 1874 and the abolition of the State Police, the Texas Rangers again came into being. Know as the Frontier Battalion, the Rangers were divided into six companies under the direction of Civil War veteran Major John B. Jones. Although the battalion’s primary duty was to defend the frontier against Indian marauders, the Rangers soon found themselves dealing more with white and Mexican fugitives and outlaws than with “hostile” Indians, now pushed into the far West. During Reconstruction many young Texans had rebelled against the northern occupation. Men such as John Wesley Hardin, Ben and Billy Thompson, John King Fisher, the Taylors of DeWitt County and the Horrells of Lampasas County now found themselves in trouble with the law and invariably became fugitives from the Rangers, who as often as not had more interest in a large reward than in punishing criminals.

Though still concerned with Indian raids and general lawlessness, Governor Coke felt the need for another special force—not under the control of Major Jones—that would act separately. To lead this unit, he chose Leander H. McNelly, weak physically but a powerful leader. McNelly’s force was given the unmanageable title of Washington County Volunteer Militia Company A because Captain McNelly chose most of his recruits from near his home in Washington County. The McNelly company was better known as “McNelly’s Rangers,” “State Troops,” or “McNelly’s Company.” Although not officially part of the Frontier Battalion, the company was considered by all as an adjunct to the battalion, no different from Companies A through F. McNelly’s initial task was to settle the Sutton-Taylor feud in South Texas, primarily in DeWitt, Gonzales and Karnes counties. But after the devastating raid by Cortina’s bravos near Corpus Christi in early 1875, McNelly was sent to the Nueces Strip to combat Mexican bandits. He replaced Captain Pat Dolan of Company F, who had found little to do because he chose to remain on Texas soil.

McNelly was a different breed, however, and he treated bandidos from Mexico the same way Jones and his Frontier Battalion treated Indians—kill the raiders and destroy the gangs. McNelly’s mission on the border was simply to end cattle rustling by whatever means. McNelly organized a spy system to provide information on coming raids. Suspected raiders were tortured by his unofficial executioner, Jesus Sandoval, and left hanging from tree limbs after inform-ation was squeezed out of them via the noose. McNelly did not like this method, but on the Nueces Strip where the nearest jail could be 100 miles away, he realized that released prisoners would end his surprise raids. Ranger veterans of the Mexican War were still known as los diablos Tejanos, and under McNelly they gained the nickname of Texas devils. During these years no other company earned such a reputation as McNelly’s—a tough fighting force that would show no quarter.

When McNelly was dumped because of his high medical bills (he had tuberculosis), leadership of the Special Force fell to J.L. “Lee” Hall, then Thomas Oglesby, after which it was discontinued. No one ever accomplished as much as McNelly in fighting lawlessness, and no one maintained the tradition of accomplishing a great deal with as few men, all of which contributed to the Texas Ranger mystique.

During the first decade of the Frontier Battalion’s existence, Rangers were involved in such conflicts as the Mason County War, the Horrell-Higgins Feud of Lampasas County, the El Paso Salt War and the Kimble County Roundup—actions accomplished with little loss of life. Although they had a reputation for shooting first and asking questions later, the men under Jones’ leadership were well aware of methods that are used by law enforcement officers of today. It was important to deliver prisoners safely to jail or court; prisoners were not to be murdered under the guise that they had been shot while attempting to escape (which was done during the State Police era). Due to the bat-talion’s success, by the mid 1880s there was little frontier left. Still the force continued its existence until 1900, when a court order ruled that only commissioned officers could execute criminal process or make arrests. Ranger privates were now without a job. This in effect destroyed the Frontier Battalion, even though there was no longer a real frontier.

During the closing years of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th, many notable Ranger captains continued the Ranger tradition and upheld the mystique. Ranger officers still protected the border against marauders from across the Rio Grande, pursued cattle thieves, and long before the Civil Rights movement began, shielded blacks from white lynch mobs. In 1901 the legislature reduced the force from six to four companies, each limited to a captain and 20 men. Even so, various captains made names for themselves: James A. Brooks, William J. McDonald, John H. Rogers and John R. Hughes, the “Border Boss.”

During the early decades of the 20th century, violence increased along the border, not only due to bandits but also because of German intrigue in Mexico. In 1916 Francisco “Pancho” Villa raided Columbus, New Mexico, which increased border tensions. Both regular and special Rangers now brought shame on the Ranger tradition by senselessly killing upwards of 5,000 Hispanics during the years before 1920. The most notorious incident took place in November 1917 at Porvenir in Presidio County. Known as the Porvenir “massacre,” 15 Mexicans were brutally murdered, allegedly because they had earlier participated in a raid on an Anglo ranch. Although the grand jury of Presidio County took no action against the Rangers, Governor W. P. Hobby disbanded Company B and dismissed five Rangers for their actions in the massacre.

Due to an official investigation forced by Representative Jose T. Canales of Brownsville, the Rangers were completely overhauled in order to regain public confidence. Ranger companies were maintained, but each was reduced to only 15 men. Reforms raised the standards for becoming a Ranger, demanding men of high moral character. Public confidence eventually returned, helped by reform-minded captains such as William L. Wright, Thomas Hickman and Frank Hamer. During the 1930s, Rangers mainly guarded the border against smugglers and rustlers and protected federal agents. Rangers also prevented damage and death during labor strikes, dealt with the Ku Klux Klan, and tamed the oil boomtowns.

The Great Depression brought turmoil to the Rangers. The force was never more than 45 men. They depended on their own horses or free railroad passes for transportation. In 1932 they openly supported Ross Sterling against Miriam A. Ferguson in the Democratic primary for governor. Ferguson won and after taking office in 1933, fired every Ranger who had supported Sterling, 44 in all. They were replaced by her supporters, but those men did not have the qualities needed to be Rangers. During this bleak period, Texas became an outlaw’s dreamland, with notorious criminals such as Clyde Barrow, Bonnie Parker, George “Machine Gun” Kelly and Raymond Hamilton grabbing headlines.

James Allred became governor in 1935, promising law and order. The legislature created the Department of Public Safety, which ran three forces: the Rangers, Highway Patrol and a Headquarters Division which oversaw a scientific crime lab that emphasized traditional detective work. The Rangers now were part of a larger anti-crime unit. Although much of the Rangers’ work was similar to that in their early days, science now influenced many of their actions. Lawbreakers were more often punished through the courts, rather than in shootouts on the open range (although shootouts did still occasionally take place).

In 1938 Homer Garrison became director of the Department of Public Safety (DPS) and some of the “glory years” returned. During WWII Rangers protected plants, dams and factories from sabotage. In the 1950s, Rangers worked on more than 8,000 cases. Due to their effectiveness, the force was increased to six companies, and by 1961 each company contained 62 men. During this period captains such as Alfred Allee and Manuel T. “Lone Wolf” Gonzaullas proved their worth.

Although the stereotypical Texas Ranger was a white, Anglo-Saxon male, through the years the force included Mexicans, Indians, and in more recent years, women and blacks. The mythical “One Riot, One Ranger” may be apocryphal, but the Ranger mystique created in the wild and woolly early years and developed during the decades of the Frontier Battalion is maintained today.

Was McNelly a Texas Ranger?

It has been claimed that Captain Leander Harvey McNelly—the subject of a recent Hollywood movie, Texas Rangers—was not a Texas Ranger! The movie shows him leading a group of young Rangers against ace cattle rustler and outlaw King Fisher (a real outlaw, then a real lawman).

If McNelly wasn’t a Ranger, how could Hollywood have made such a gaff?

He was and he wasn’t—if you go by the technical meaning of the term Texas Ranger. In 1874 Governor Richard Coke created the Frontier Battalion to defend the ever changing Texas “frontier line” against marauding Indians. The battalion was made up of six companies, each led by a captain and each composed of 75 men. At the same time, Coke felt he needed a force to handle “internal problems” in the “civilized” counties in the eastern half of the state. To deal with white outlaws and family feuds, the Washington County Volunteer Militia Company A was created, headed by a young Civil War veteran, Leander H. McNelly. He was given the rank of captain and allowed to recruit up to 50 men.

Thus, the company McNelly recruited was not technically part of the Texas Rangers, but rather a militia. Yet this is only a matter of semantics. In practice, those young militiamen did the same dangerous work as did members of the Frontier Battalion’s six companies. They went after hard men who did not want to be chained, jailed or led to the gallows. The general populace considered McNelly’s men as much Rangers as they did the men in the Frontier Battalion.

And McNelly himself?

In November 1875, McNelly and 30 men were on the banks of the Rio Grande, contemplating crossing the river to pursue cattle thieves. On the 18th he telegraphed his boss, Adjutant General Steele:

A party of raiders have crossed two hundred & fifty cattle . . . they have been firing on Maj. Clendenin’s men. He refuses to cross without further orders. [but] I shall cross tonight . . . .

He signed it “L. H. McNelly, Captain Commanding Rangers.”

Later he again telegraphed Steele that he was about to cross the river (a violation of international law) with his 30 men. He signed this communication simply: “L. H. McNelly Captain Rangers.”

Once he had forded the Rio Grande, he still communicated with his superiors:

The Mexicans made several attempts during the evening to dislodge us but failed. U.S. troops withdrew last night. I am in temporary earth works and have refused to leave until the cattle are returned. The Mexicans in my front are about four hundred. . . . L. H. McNelly Captain Rangers.

A few days later on the 21st, after Captain McNelly had re-crossed the river to send a message to the mayor of Camargo, saying he would keep his men in Mexico until the stolen cattle were returned, he signed the letter “L. H. McNelly, Captain Commanding, Texas Rangers.”

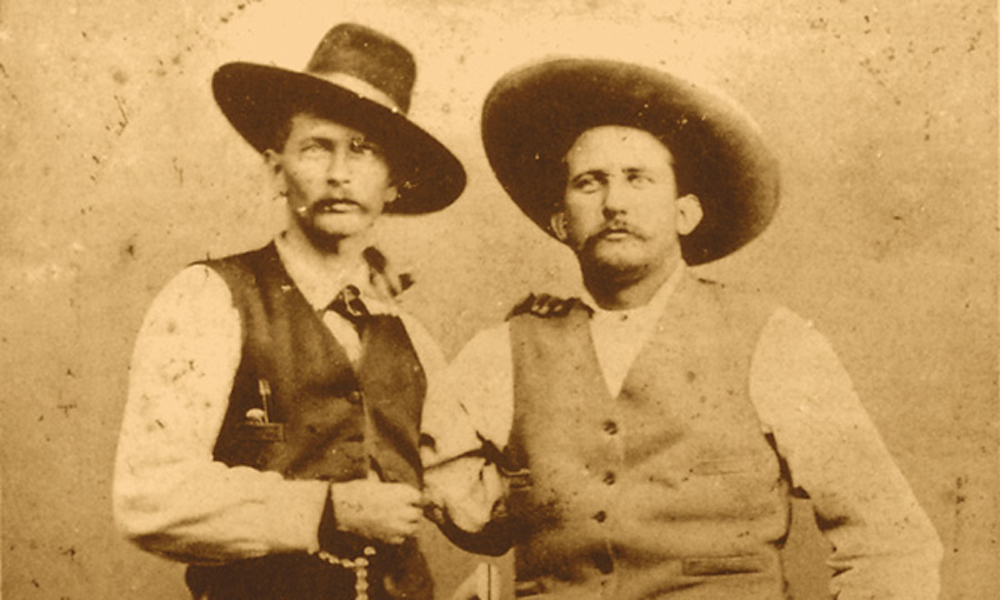

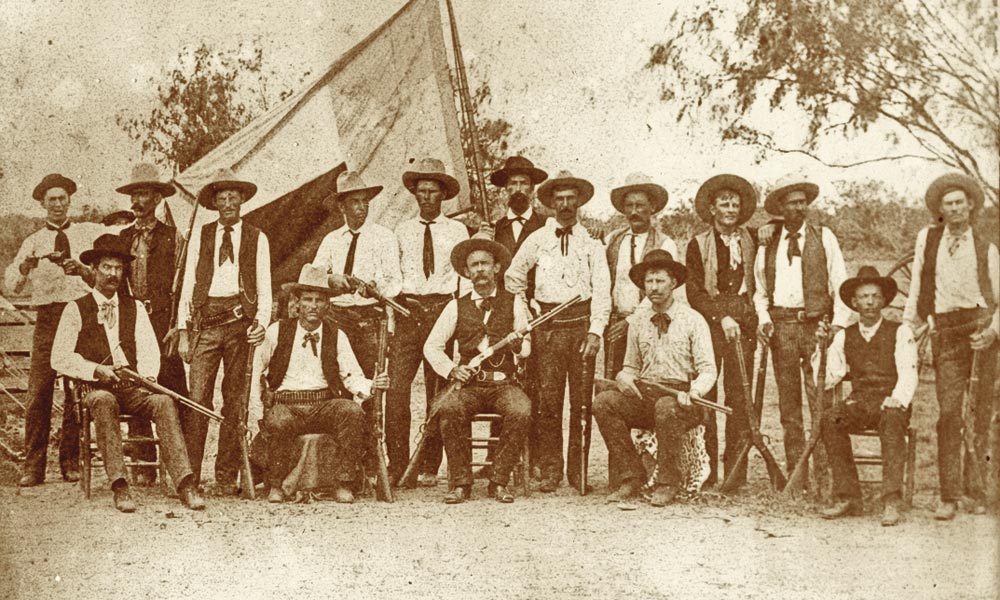

Near the end of his career McNelly had a group photograph made of his camp, showing 25 men lined up and himself seated by his tent. Years later McNelly’s wife identified the photograph as “Picture of Capt. L. H. McNelly’s Company Texas Rangers taken in 1877.”

Technically McNelly was a militiaman, but he and his wife and his men and Texans in general considered him a Texas Ranger, just like the men in the Frontier Battalion.

Semantics be damned! McNelly was a Texas Ranger!

Chuck Parsons has been interested in the Texas Rangers for decades, and has written books about Rangers Captain C.B. McKinney and T.C. Robinson (McNelly’s lieutenant). He also wrote the first full-length biography of Captain L.H. McNelly. Parsons was the True West Answer Man from 1983-2000 and is currently editor of the NOLA (National Association for Outlaw and Lawman History, Inc.) Quarterly and Newsletter.