A Ute Elder Shares His Thoughts on the So-Called

“Utah War.”

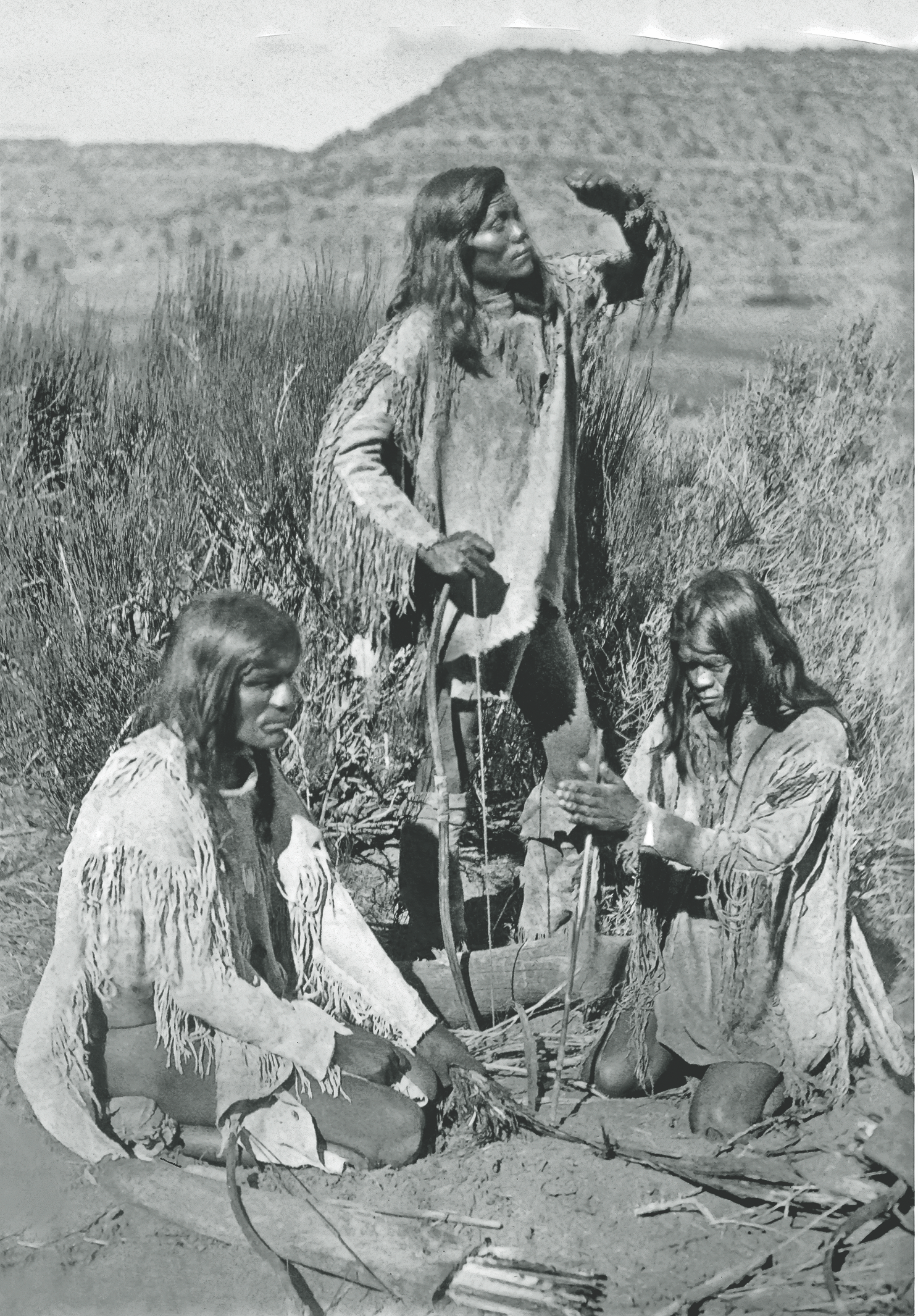

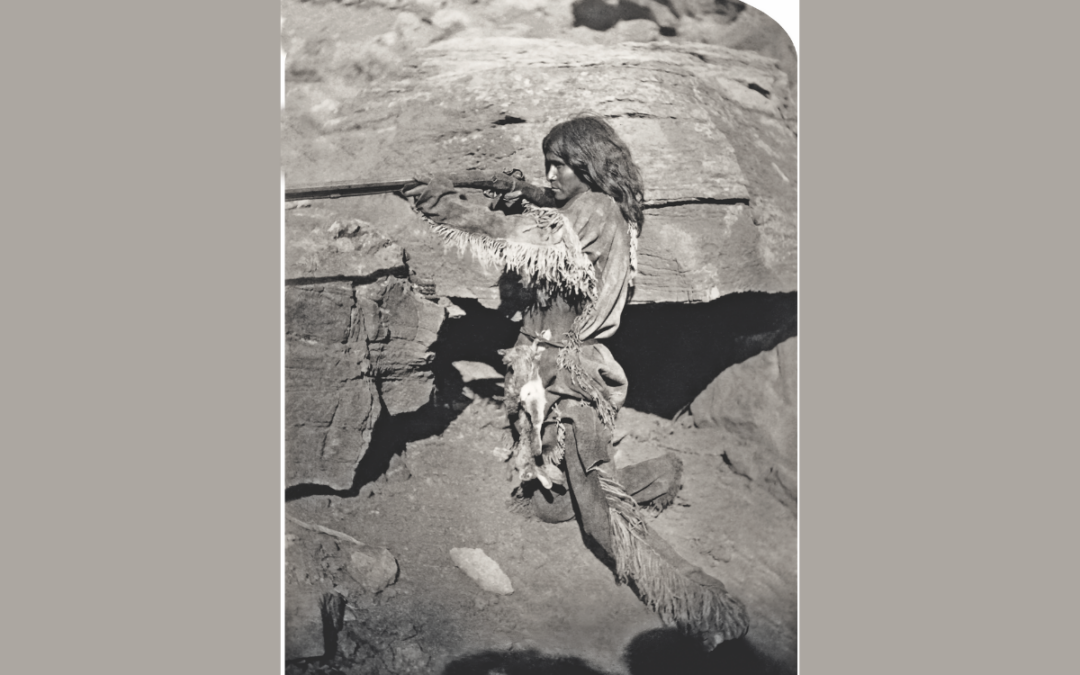

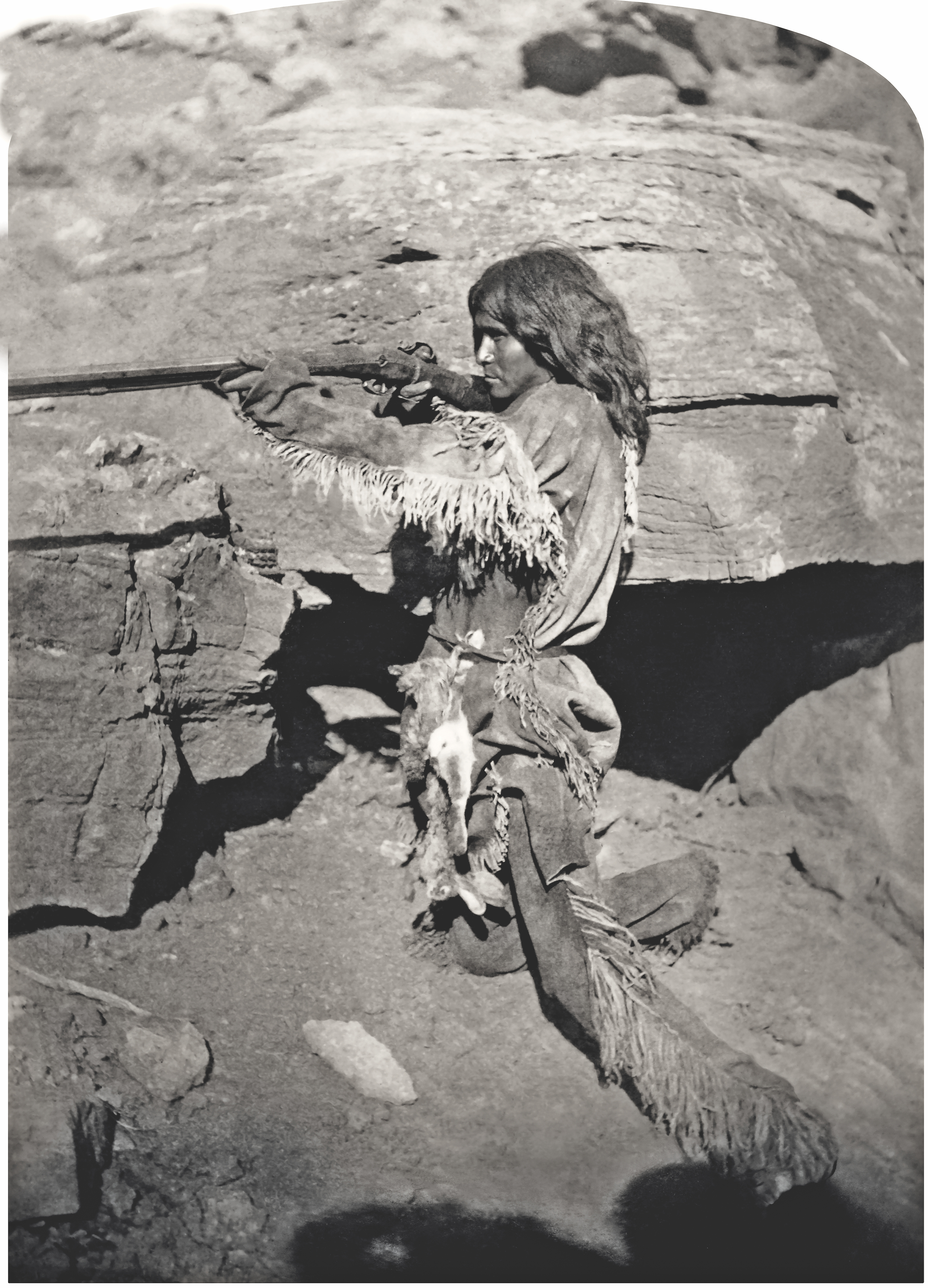

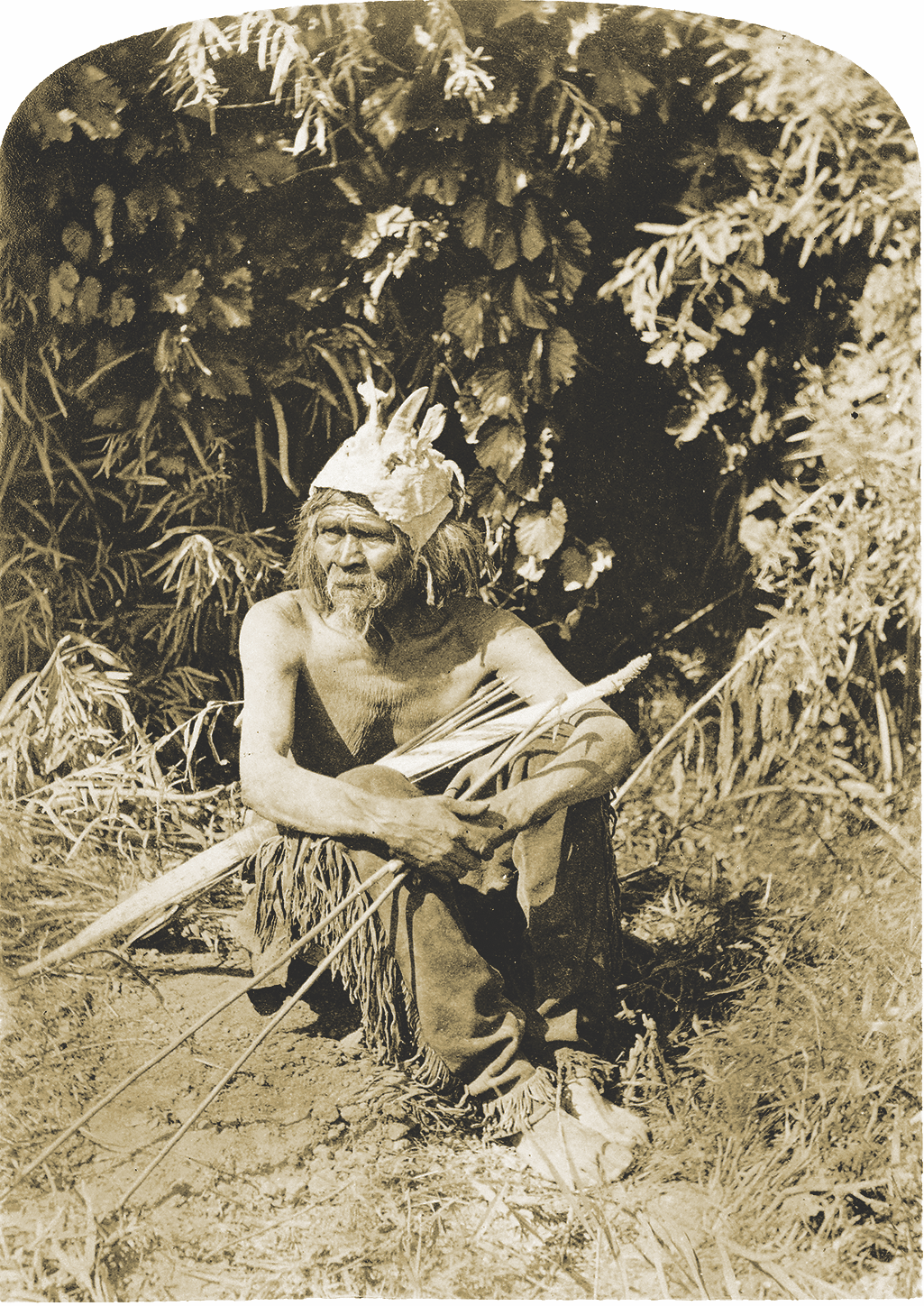

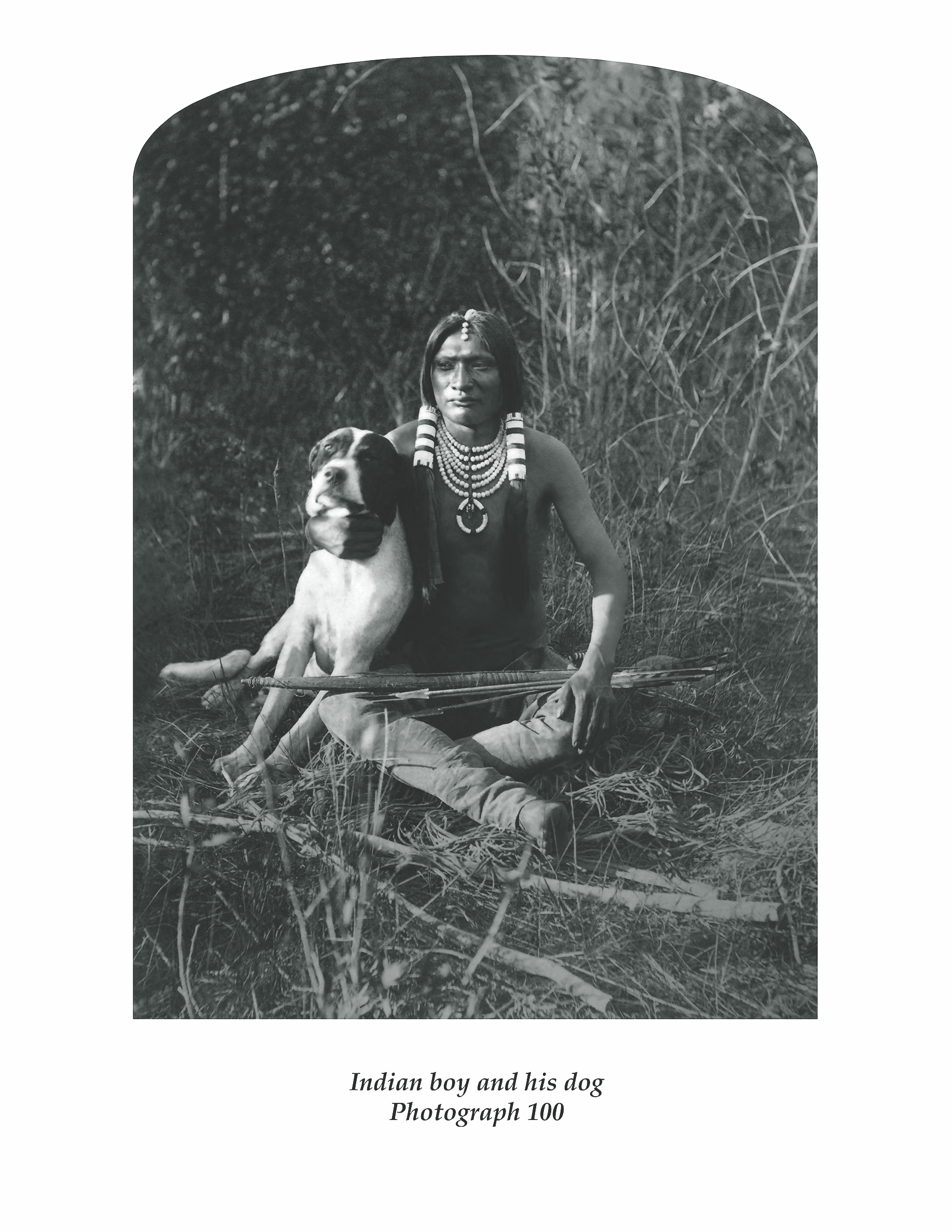

A skilled Paiute hunter demonstrated his marksmanship in 1873. Although the Paiutes initially welcomed Mormon settlers in 1851, their arrival also resulted in numerous epidemics. Some bands of Paiutes lost over 90 percent of their population to various diseases throughout the decade that followed.

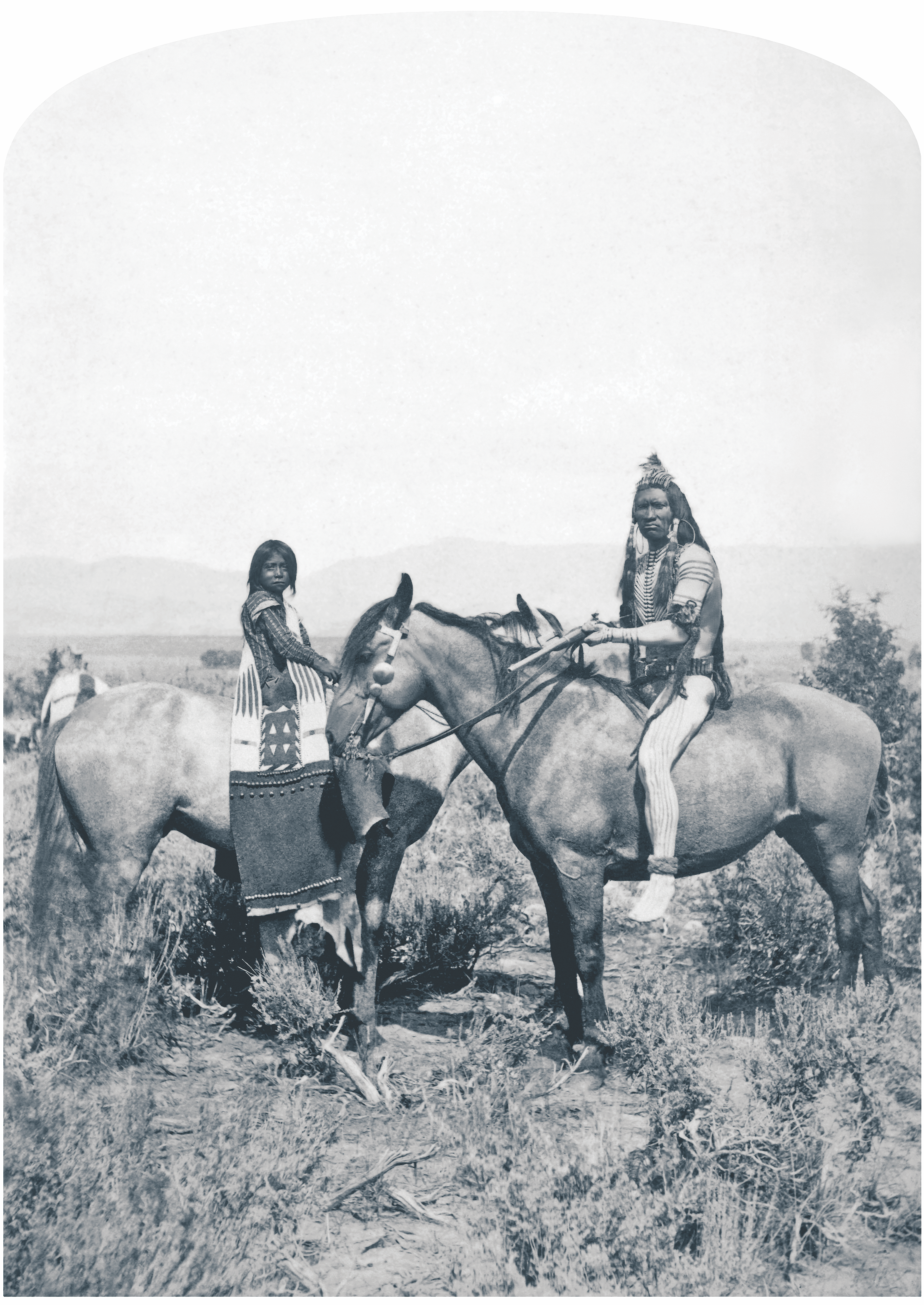

Prior to the arrival of Mormons in 1847, thousands of Shosh-onean people occupied northern Utah. No actual population number has been assigned, but my guess would be approximately 10,000, mostly Ute and Northwestern Band Shoshone, and a lesser number of Goshute Indians (desert-dwelling Shoshone). Most scholars estimate that throughout the Western Hemisphere, disease and warfare reduced the native population by 90 percent by the turn of the 19th century.

My understanding is that both the Ute and Shoshone tribes knew about the Mormon entrance in the area and monitored their movements. If the Native people were as savage as some believed, they would have attacked the Mormons in the narrows of Immigration Canyon, where they would have been an easy target for Indian warriors. My understanding is they did not attack because they were aware that most of the growing number of wagon trains were passing through enroute to California, especially those following the Oregon Trail. The word “passing through” is significant, because in the case of the Mormons, they did not pass through: they were there to stay.

Several books on Utah/Indian history state that both tribes visited the Mormons shortly after they arrived in the Salt Lake Valley. Like the Wampanoag and Narragansett on the East Coast, the tribes visited the newcomers with the purpose of accessing firearms to use against each other. According to Shoshone lore (Ontko), they were all one big nation at one time. At some point, different bands began breaking away from their original homelands near the Blue Mountains of northeast Oregon and settling in other parts of the West. Over time, languages began to change, and the bands’ relationships began to weaken and eventually dissolved. Consequently, they would fight over territory when they encountered each other. During this time, the Ute and Shoshone people fought numerous times over territory and raided each other for horses.

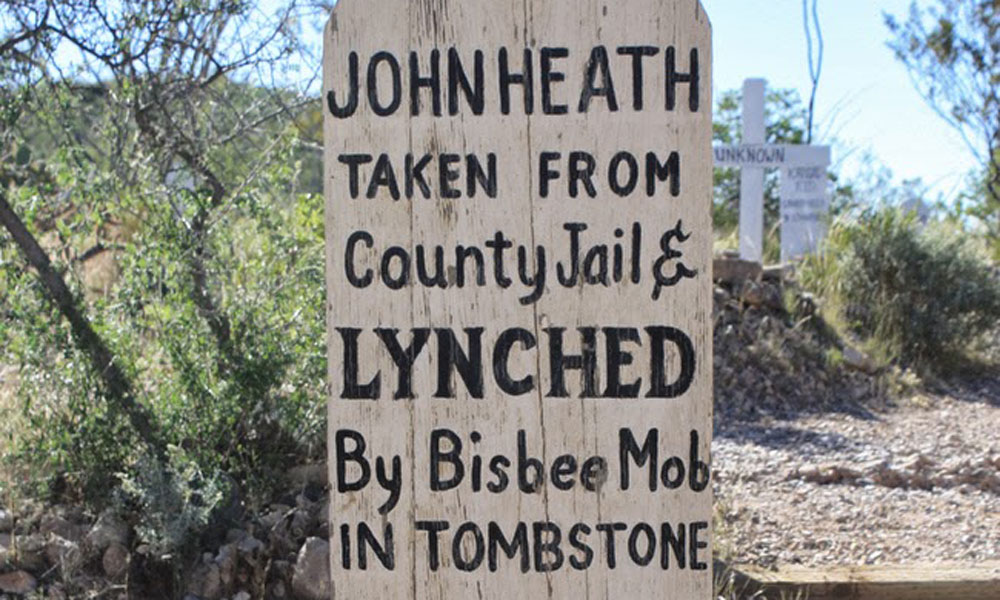

The Utah War (1857–’58) is known by many names. It was an armed confrontation between Mormon settlers and the armed forces of the U.S. government. However, I feel it should be more aptly named “No Utah War” because there were, to my knowledge, no standing battles between the Mormon settlers and the U.S. military. In 1857, tensions were brewing in Utah between Brigham Young and Mormon Church members and the federal government over governance and autonomy within the territory. By declaring himself governor, Brigham Young was acting independent of the United States. Because of this fight for control, President Buchanan sent armed forces of the U.S. government to quell “the escalating tensions.” Although the war featured no significant battles, it included the Mountain Meadows Massacre, in which Mormon militia members and Mormon settlers disarmed and murdered about 120 pioneers traveling to California on September 11, 1857.

The Fancher and Baker parties from Arkansas were traveling through a remote part of southwestern Utah when they were attacked. The Mormons claim that one of their esteemed apostles, Parley Pratt, was unjustly killed by someone from Arkansas and this precipitated the attack. There remains the possibility that Pratt may have contributed to some of this hostility by his personal behavior.

I quote my old friend, Will Bagley: “As the Fancher and Baker parties trekked west, they may have heard that an aggrieved husband had killed Parley Pratt, one of the original apostles of the LDS church, in western Arkansas some two weeks after they left the state. Hector McLean, outraged at Pratt’s appropriation of his wife, had tracked the apostle up and down the Mississippi Valley and brutally murdered him on the Arkansas border near Fort Smith. No one in the Fancher or Baker parties had anything to do with the affair, but it would forever be linked to their fate.” Unfortunately, Mormon settlers believed the tale that Pratt was killed by someone in Arkansas, and this angry sentiment was passed on to Mormon settlers from town to town up and down the Utah corridor. Because of this misconception, the Mormons were forbidden to sell food and supplies to the Fancher-Baker party and branded them as murderers of the beloved Parley Pratt.

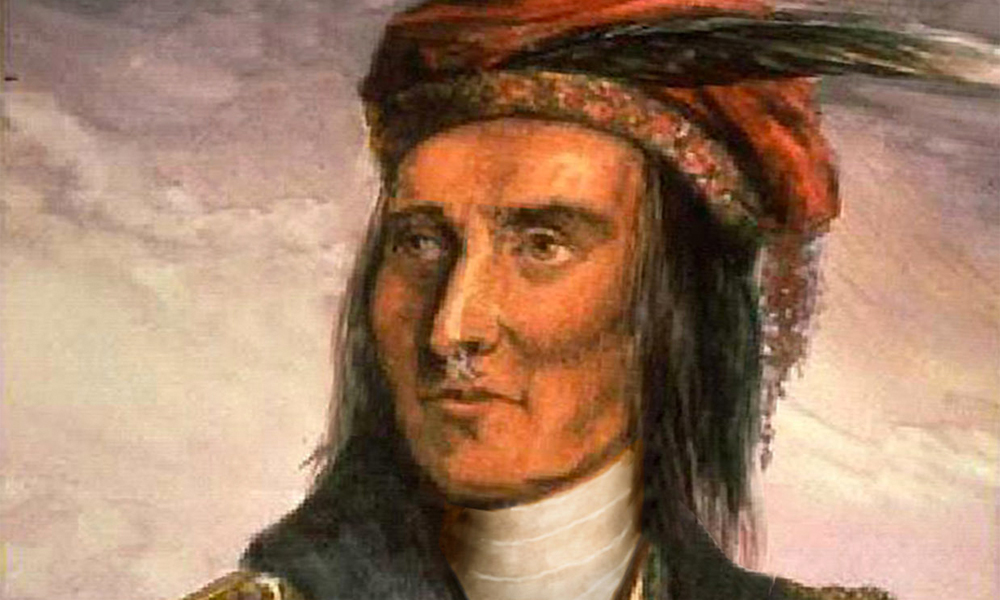

During this time, several attempts were made to entice the Utes to join the Mormons in the war against the U.S. government, the “Americats.” According to the Book of Mormon, Indians were considered “the battle axe” of the church. The Utes declined to join the war. War-Chief Wakara/Wookara was suspicious, especially since the tension was building between him and Brigham Young as the Mormons pushed farther into traditional Ute territory. By this time, the settlers had already pushed the Utes out of Utah Valley and had taken over and began destroying the Utes’ valuable fishery at Utah Lake. The lake was a fish resource that, according to historian Jerod Farmer, a professor of History at University of Pennsylvania, contributed 30 percent of the Ute people’s diet at one time. It is believed that this growing conflict would eventually lead to the death of one or both leaders in the years to come (Bagley and Mueller). As for the invasion of Mormon crops by a plague of locusts—now referred to as Mormon crickets—the Goshute had adapted to this phenomenon long ago by making the locust a key source of their diet—as much as 20 percent, according to Gavin Noyes, who spent many years working with the Confederate Tribes of Goshute.

In short, the Indians, neither Ute, Shoshone nor Paiute, were active participants in the Utah War. The Indians refused to be implicated or serve as the “battle axe” for the LDS church. And although some Indians were recruited to join the Mormon Militia (called Nauvoo Legion) and take the blame for the bloody Mountain Meadows atrocities, those Indians were likely renegades, splinter groups of Southern Paiutes from Nevada, or Shoshones from out of the state. The official position of the Paiute Tribe of Utah is that they had no part in the massacre. Although it was supposedly the job of the Indians to kill the women and children of the Fancher-Baker party, my understanding is that the main killers were members of the Mormon Militia and Mormon settlers, some of whom were dressed up as Indians. Recently, forensic examination of the remains of individuals from the Fancher-Baker party revealed that some of the victims were shot execution-style at the base of their skulls, according to discussions with Kevin Jones, former Utah State Archeologist. If the renegade Indians were enticed to attack the wagon train for the spoils, they received very little if any of the real loot and had to scavenge what was left on the wagons. Some of the Fancher and Baker members were well off and carried valuables with them on their journey west. That loot was acquired by Mormon settlers and included precious metals of gold and silver, cattle, racehorses and other valuable items necessary for resettlement in another part of the country.

In the end, it was the Indians who got the raw end of the deal. They were blamed for the massacre, and generation upon generation was raised with this perception. This was the narrative that was told to me in the seventh grade at West Junior High School, Uintah County, in northeastern Utah.