Nobody messed with Sarah Bowman, “The Great Western.”

She was a giant among women—hell, she was a giant among most men—this “Amazon of the Border” who was a military hero in the Mexican War, a groundbreaking businesswoman, a “good specimen of the frontier woman” and, as some put it, the prototype for “the whore with a heart of gold.”

They called Sarah Bowman “The Great Western,” borrowing the name of the world’s largest steamship. It fit the woman who was at least six feet tall, maybe six-two, who weighed over 200 pounds, had enormous breasts and an hourglass figure.

The nickname was applied because of her size, but it stuck because of her grit. This was a woman of uncommon courage and determination who didn’t, frankly, take guff from no one.

She was born Sarah Knight in 1812 or 1813 in Tennessee or Missouri—she was never clear about her early days (she also used the surname Borginnis and Bourjette). Along the way, she accumulated several husbands (not always with the benefit of clergy, which spoke to both her nature and the necessity of the times) and came into her own as she traveled with Gen. Zachary Taylor’s Army in the Mexican War from 1846-48. She had a sense of self assurance that stunned both men and women.

One historian noted she “had the reputation of being something of the roughest fighter on the Rio Grande and was approached in a polite, if not humble, manner.”

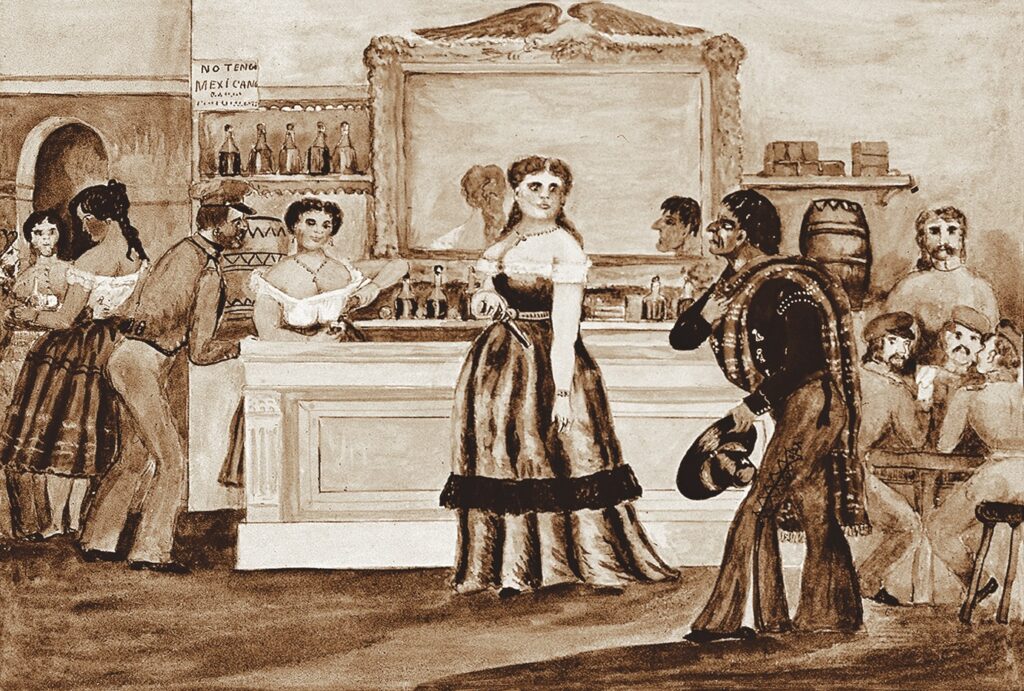

Courtesy West Point Museum Collection, United States Military Academy

And woe to those who didn’t understand that, as shown in the following story, recounted in an article by Mercedes Graf in Minerva: Quarterly Report on Women and the Military:

One day a trooper let out a wolf whistle and muttered under his breath as Sarah walked by: “The Amazon whirled with the litheness of a panther. …Before the startled heckler knew what was happening, she had hoisted him like a sack of feathers and pinned him. . . . Effortlessly she held him there with one hand; her grayish-green eyes boring straight into his. Finally, the astonished soldier found his tongue…he apologized. Suddenly, she dropped her hand and the unhappy trooper plummeted back to earth. The woman turned abruptly and stalked away—she had not uttered a single word during the entire incident.”

What drew her to the Mexican War was never explained, but drawn she was. It was honorable in those days for wives of enlisted men to become “camp followers” (before that phrase was dirtied to mean loose women). The wives enrolled in the Army as cooks, laundresses, nurses and seamstresses. (The most famous camp follower was “Lady Washington,” who spent most of the Revolutionary War camped with her husband, Gen. George Washington.) Sarah did all those jobs and more, sometimes picking up a weapon, often using her strength to drag or carry men off the battlefield.

A history project from the University of Texas at Austin reports that Sarah first distinguished herself as a fighter in March 1846 at the crossing of the Arroyo Colorado, “when she offered to wade the river and whip the enemy single-handedly if Gen. William Jenkins Worth would lend her a stout pair of tongs.”

Two months later during the bombardment of Fort Brown, she refused to seek safety with the other women and continued to operate the officers’ mess for a week while under siege. She didn’t stop even when a tray was shot from her hands or when a shell fragment pierced her sunbonnet.

“Her fearlessness during the siege earned her another nickname, the Heroine of Fort Brown,” the university’s Handbook of Texas notes. At a celebratory dinner after the battle, a special toast was offered for her, reports Graf in Minerva: “To The Great Western—one of the bravest and most patriotic soldiers at the Siege of Brown.”

During the Battle of Buena Vista, she distinguished herself again by loading cartridges and carrying wounded soldiers to safety from the battlefield.

Sarah “was acclaimed in General Zachary Taylor’s Army, from the highest general to the lowliest drummer boy, for her consistent courage in the front line of battle,” Graf notes.

Sarah went to Mexico with the Army, opened a “hotel” in Saltillo that provided drink and women, and stayed until after the war. But in July 1848, she wanted to accompany the Army to California. Her husband was gone by then and only married women were allowed to travel with the Army. In a scene that sounds straight out of Hollywood, she rode along the line of men yelling, “Who wants a wife with fifteen thousand dollars and the biggest leg in Mexico? Come, my beauties, don’t all speak at once. Who is the lucky man?” A dragoon named Davis finally stepped forward and the Great Western was marching with the Army yet again.

She landed in El Paso, where she became the first female in the town to run a business. Her hotel and restaurant—she reportedly was an incredible cook—catered to gold diggers on the way to California, who stopped for room, board and “entertainment.” Historians allude to her as a madam, but give no real details on her “hotel brothels,” except to report that “business was good” and nobody had anything but kind words for her. (One biographer insists she operated only one brothel and that all the rest of her businesses were legitimate hotels and restaurants. Others note she was a prostitute now and then to support herself, but hasten to add that hardly defined her life.)

Eventually she married a German upholsterer named Albert J. Bowman and they settled in Fort Yuma in the Arizona Territory. Sarah opened yet another restaurant and made a real home in Yuma. She couldn’t have children, but she adopted several orphans (some of whom may have been Mexican).

A tarantula bite killed her. She was buried with full military honors in the Fort Yuma post cemetery on December 23, 1866—reportedly the only woman to be so honored. In 1890, the Depart-ment of Army exhumed 159 bodies from that resting place and moved them to the national cemetery at the Presidio in San Francisco. Sarah Bowman, the Great Western, was among them.

Her legend lives to this day. A recent historical novel by Lucia St. Clair Robson is appropriately titled Fearless: A Novel of Sarah Bowman.

The author tells True West she used the Great Western as her heroine because “I was intrigued by a woman who could cold-cock a man and inform him he was a son-of-a-bitch as he went down.”

Somewhere, you can bet Sarah Bowman is smiling.

Did you know?

Army wives—whether they traveled with the soldiers or stayed behind in established forts—had to be made of stern stuff. It’s reported that Libbie Custer was particularly strong. Judy Alter’s Extraordinary Women of the America West reports: “When word was brought to her of Custer’s death [at the Battle of the Little Bighorn], she threw a wrap over her dressing gown and accompanied the captain to the twenty-five other widows of that battle to offer them consolation.”