The Bowie knife is an iconic symbol of American toughness and independence. Yet, its true origins are often misunderstood. The knife became famous after Jim Bowie’s involvement in the Vidalia Sandbar Fight, in which he used a large knife described as “a big butcher knife.” However, there were no photographs of this knife at the time, so the description was applied to any large, hefty blade. Most likely, the knife was a straight-backed butcher knife similar to what we today consider a slicing knife. This design resembled the Spanish Dagger singleedged knives that were common in the 19th century.

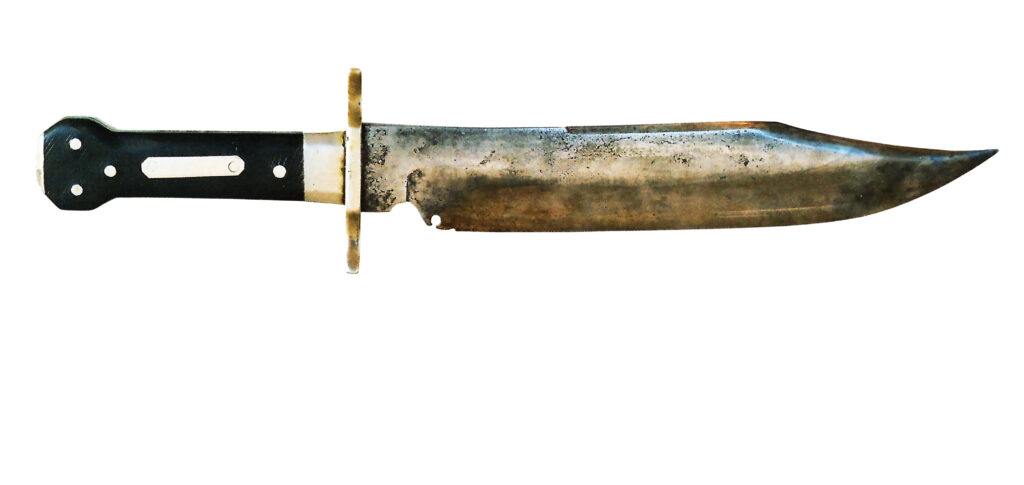

Most early knives associated with Jim Bowie and his brother, Rezin, were variations on the Spanish Dagger style. The knife Rezin gave to actor Edwin Forrest, for instance, was a later version with a sharpened top edge, distinguishing it from the earlier butcher-style knives. It’s this version, modified from the traditional Spanish Dagger, that likely influenced Jim’s famous blade, especially the one he took to the Alamo. There’s still room for debate about the exact knife Jim Bowie carried during the Battle of the Alamo, but I believe it closely resembles the one described in Robert Abel’s book. This knife, which was made by James Black, a respected silversmith and blacksmith of the time, had a clipped point and double guard, marking a departure from earlier Bowie knives. Black, known for his fine craftsmanship, likely produced two knives for Jim Bowie—one was the knife he was requested to make, and the other, with a more Scottish influence (given Bowie’s heritage), was likely the one Jim selected.

James Black’s design incorporated features similar to a Scottish dirk, such as the straight clip and substantial double guard. When Bowie picked up his knife, he chose the version he thought was best suited to his needs— Black’s clipped-point design over another, simpler version marked “Bowie number 1,” which lacked a guard and had an upward-angled handle.

The Bowie knife’s distinctive hooked point evolved from the German messer, a type of knife with a curved blade used in combat. The messer was notorious for its ability to act as a sharp claw on the backstroke, a feature that made it particularly deadly in close-quarters fighting. These knives were often around 18 to 26 inches long and were used extensively by pirates for boarding ships. Unlike the elegant fencing swords of the time, the messer was a practical, rough-and-tumble weapon designed for serious combat.

Smaller messers with double guards had already gained popularity in America before Jim Bowie’s time. These knives resembled the classic Bowie knife as we know it today. As demand for larger, more versatile blades grew, knife makers began producing more Bowie-style knives, including a 10-inch blade variety made in Solingen, Germany. Thousands of these knives were imported to America, and their basic design, unchanged for centuries, continues to be made in Solingen to this day. The popularity of the Bowie knife soon reached new heights. It became fashionable to carry one, replacing both the sword and sword cane in many places. The Bowie knife was seen as an essential tool for survival, and it was carried by rich and poor alike. The phrase “No man, be he worth a leek, be he mighty or be he meek, but he bare a basilard” reflected the growing importance of carrying a blade, similar to the medieval basilard dagger.

Bowie knives could be carried openly or concealed. One method, especially popular in the South, involved suspending the knife behind the neck, allowing it to be drawn like an arrow from a quiver. This tactic worked well for leaner men but proved more difficult for those of stockier builds. So common was this method of carry that it became a warning sign during an argument: scratching the neck could be mistaken for drawing a knife, sparking a fight.

In contrast to modern knife fights, where both opponents are often injured, the Bowie knife was used with a level of precision that allowed the wielder to control the fight. In the 19th century, combatants aimed to disarm and disable their opponent swiftly, often striking their opponent’s weapon aside before targeting a vulnerable part of the body. The key to success was always maintaining distance—strike, then step back to avoid a counterattack.

Bowie knives were designed with a particular fighting style in mind. Early versions of the knife had handles angled upwards, making it easier to fight with the edge up, striking with the back of the blade against another knife. Some Bowie knives also featured a brass parry strip to reinforce the blade during these strikes. Later, the technique evolved, and the edge of the knife became the main point of contact in a strike, similar to saber fighting.

The Bowie brothers themselves were skilled in both sword and knife fighting. They honed their skills in New Orleans, a city rife with duels and violence during the 19th century. New Orleans, a cultural melting pot, was known for its high number of duels, and it was here that Jim Bowie made his name during the infamous “Rough fight” at the Sandbar Duel. Though dueling had been outlawed, men like Bowie and his brother Rezin were still deeply involved in this dangerous practice.

In the Sandbar Duel, Jim Bowie was called upon to act as a second for Gen. Montfort Wells. When the duel took an unexpected turn, with one of the combatants being shot, the real fight began between the seconds. Despite being severely wounded by a gunshot, Jim Bowie, armed with his brother’s large knife, fought off four attackers, killing one and injuring others. His dramatic survival and ability to fight back despite serious injuries cemented the Bowie knife’s reputation as a weapon of deadly efficiency.

The role of the Bowie knife as a hunting tool should not be overlooked. It was prized by frontiersmen and hunters, who often used it for both survival and defense. In the 19th century, men were expected to fight off wild animals, such as bears, with nothing more than a knife. The knife was an essential part of frontier life, especially for hunters who needed it to skin and butcher large animals like bears. Confederate Gen. Wade Hampton was renowned for his ability to kill bears with a Bowie knife, a skill passed down to many hunters of the era.

In the later 1800s, as firearms technology improved with the advent of the Winchester M1873, hunters increasingly relied on rifles, but the Bowie knife continued to be a trusted companion, especially in the rougher conditions of the frontier.

During the Civil War, the demand for Bowie knives surged. Confederate blacksmiths made large, heavy knives to replace short swords in the infantry, and these knives were crafted with the same principles of speed and efficiency that made them so valuable in combat.

Though smaller knives have taken over the market in recent times, the Bowie knife has never lost its place in American history. Despite the push by manufacturers to produce cheaper, more compact blades, the Bowie knife remains a symbol of rugged independence, practicality and the spirit of frontier survival. The legend of the Bowie knife endures because it works— whether for combat, survival or simple utility, this iconic blade has stood the test of time.