A LONG ROAD TO THE BATTLE AT THE ALAMO

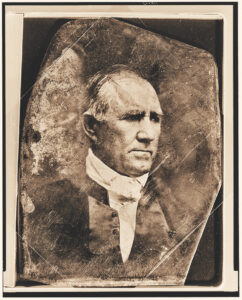

Mexico had its hands full with Texas—the northern portion of its state Coahuila y Tejas—in 1835. Many Texas citizens wanted separate statehood from Coahuila within the Mexican confederation. This proved a dangerous position, because Texas’s first citizen of colonization, Stephen F. Austin, remained jailed in Mexico since the previous year for urging Texans to begin drawing up plans for separation. The issue also divided Texas. Some sought peaceful existence with the Mexican government. Others pushed for stronger action for statehood. These factions eventually separated into the “Peace” and “War” parties. Mexican President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna centralized his power in 1836 and kept an eye on Texas. Stephen F. Austin, still in custody in Mexico, awaited passage of a new amnesty law that would ensure his freedom. He wrote letters to associates assuring them that Texas had friends among Mexican officials. Austin also praised Santa Anna’s friendship toward Texas and felt confident that it would soon become its own state within the confederation.

By the spring of 1835, Jim Bowie had shaken off his lethargy following the death of his wife and resumed his interest in land. The legislature of Monclova, capital of Coahuila y Tejas, appointed Bowie as a commissioner to oversee the distribution of 1,771,200 acres around Nacogdoches, Texas, with the money raised contributing to defense against Indians. Sweetening the deal, 420,660 acres of this land went to him, with other acreage going to his cronies at bargain prices before the land hit the market. As tensions between Texas and Mexico increased, President Santa Anna sent General Martin Perfecto de Cós to Monclova to rein in the land speculators and the local government. Bowie joined Monclova’s militia and forced Cós toback off without bloodshed, but the general returned in late May and arrested Bowie and others before they crossed over into Texas. Bowie escaped with a companion several weeks later and returned to their state.

By April 1835, Sam Houston set up in Nacogdoches, Texas, where he embraced Catholicism. An entitlement to 1,480 acres of land may have served as an incentive to his conversion. Although Davy Crockett had helped subdue a would-be assassin of President Jackson that January, his political career soon faltered. Meanwhile, young William Barret Travis was occupied with his legal practice and the slave-trade. Travis also wondered about Stephen Austin’s fate and gave up any hope of Austin’s release by June. “Let them sacrifice him if they dare,” he declared. “A thousand of their contemptible ‘red skins’ shall be sacrificed to his name.” William Travis also pondered the increasing tensions with the Mexican government and impending conflict. “The rumor of troops coming to Texas in great numbers must be false. Such a measure would kindle a flame in Texas that would burn in twain the slender cords that connect us to the ill-fated Mexican confederation.”

Houston the former governor, Austin the colonizer, Bowie the adventurer, Crockett the politician, and Travis the lawyer, all moved toward the yet-to-be kindled flame. Travis, the youngest and least experienced, provided the spark that ultimately altered the map of North America.

William Travis received false information that Stephen Austin had received his freedom in Mexico by early June 1835. He soon signed “The San Felipe Pledge,” with 25 others, forming an armed volunteer company with the purpose of disarming the Mexican military at Anahuac, on June 22. They wasted little time. Eight days later, Travis bluffed Captain Antonio Tenorio— commander at Anahuac—into a bloodless surrender and signing an agreement that the Mexican detachment would abandon their post and leave for San Antonio.

Public reaction to Travis’s initiative was not favorable. Outraged members of the Peace Party feared his actions would impact Austin’s status and push them toward war. Colonel Domingo de Ugartechea in San Antonio and General Martin Perfecto de Cós in Matamoras demanded Travis’s arrest. A commander of a Mexican warship offered a $1,000 reward for his apprehension and the privilege of hanging him from his yard arm. With a price on his head, Travis laid low but expressed an opinion which may have had some bearing on events seven months later. “Let us be firm and united in defending Texas to the last extremity within our own limits,” he wrote on July 6. “In offensive war we can do nothing, in defensive everything.”

Jim Bowie soon emerged as the commander of a force in Nacogdoches on July 13. As Travis had done in Anahuac, they seized the local Mexican warehouse, removing weapons and equipment without bloodshed. Bowie also arranged for the seizure of a packet of Mexican communications, some of which laid out the plans for arresting Travis and others. These acts did nothing to endear him to Mexican authorities. Travis displayed uncharacteristic caution when writing to Bowie on July 30. “The people are much divided here,” he declared. “Unless we could be united, had we not better be quiet, and settle down for a while?” Travis later suggested a more defensive approach, when declaring, “If we are encroached upon, let us resist until our bodies and our property lie in one common ruin, ere we submit to tyranny.”

In Nacogdoches, “General” Sam Houston was appointed to treat with various Indian tribes on August 15. Two weeks later, he issued a proclamation. “Our situation is unsafe,” Houston announced. “Some Cherokees with the native Castilians, have returned to the Cherokee village from Matamoras, and say that the Indians of the prairies and a Mexican force, are about to attack this portion of Texas.” Houston requested militia from five counties be organized until United States Army reinforcements arrived. He also directed the militias to report to him as they arrived and encouraged the purchase of arms and ammunition.

Despite what William Travis had heard about Stephen Austin being freed in May, the Empresario did not receive his passport from Mexico until July 11. He sailed from Veracruz for New Orleans on July 23. Eighteen months as a prisoner affected his opinions about peaceful cooperation with Mexico. “The best interests of the United States require that Texas should be effectually, and fully, Americanized,” Austin wrote in New Orleans on August 21.

“Huzza for Texas!” William Travis wrote in response to orders for his arrest and execution for the Anahuac expedition on August 31. “Huzza for Liberty, and the rights of man!” News of a “convention of all Texas, to declare our sentiments, and to prepare for defense, if necessary,” rendered Travis almost giddy. On the same day, General Martin Perfecto de Cós wrote to Colonel Ugartechea announcing his plans of coming into Texas in person.

Stephen Austin returned to San Felipe by the first week of September, delivering a speech at a public dinner in his honor. He stressed the dangers to the rights of Texas with the destruction of the Constitution of 1824, as well as the need for a general consultation of all Texans. Four days later, Austin chaired a meeting in San Felipe, with Travis present, laying out plans for a consultation, for a committee of vigilance and safety and resolving other measures. “Principle has at last triumphed over prejudice, cowardice and selfishness,” Travis wrote to Henry Smith on September 15. “All will become united in resistance to a military government.”

On September 19, Stephen Austin passed on information from an unidentified informant in Bexar that, “The final answer of Gen. Cós had just been received—It is positive that the persons [Travis and others] who have been demanded shall be given up and that the people of Texas must unconditionally submit to any reforms or alterations that Congress has to make in the Constitution…. War then is inevitable.” In another letter he wrote, “War is upon us—there is now no remedy.” Ten days later this communication appeared as a broadside for public consumption.

Mexico aided Austin in his war prophecy. On the same day as the issuance of his broadside, a force of one hundred dragoons from Bexar arrived at Gonzales to seize a cannon which had been given to the settlers for protection. Eighteen Gonzales citizens resisted, keeping the dragoons on the west side of the Guadalupe River. When the Texan force swelled to 140 men, it violated a truce with the Mexicans, crossed the river and attacked on October 2. One unfortunate Mexican soldier died in the resulting “battle.” The Texans retained their cannon and sent the dragoons back to Bexar without loss. The flame kindled at Anahuac in June thus ignited the Texas Revolution.

Sam Houston wrote to Isaac Parker in San Augustine on October 5: “… war in defense of our rights, our oaths, and our constitution is inevitable, in Texas!… If volunteers from the United States will join their brethren in this section, they will receive liberal bounties of land… Let each man come with a good rifle, and one hundred rounds of ammunition, and to come soon… Our war-cry is “Liberty or death… Our principles are to support the constitution, and down with the Usurper!!!”

With San Augustine a good 300 miles from Gonzales, Houston either had an amazing sense of timing, or a communications system of remarkable speed.

Things happened rapidly. A Volunteer Texas Army took shape with Austin as commander, and Bowie with a colonel’s rank, his aide. In late October, Bowie led men to reconnoiter the Espada and San José missions south of San Antonio where he drove back a force under Colonel Ugartechea. Later, he defeated a larger Mexican force at the mission Concepción. The Texans then set up a loose siege of San Antonio, the Mexican troops now commanded by General Cós.

The Texas Consultation convened on November 3. It soon formed a general council and named Henry Smith as governor. It also decided to push back a constitutional convention to March. The council reassigned Austin from his position as commander of the army to a diplomatic one, sending him to the United States to raise men and money for Texas. His volunteers, in keeping with tradition, elected Edward Burleson as his replacement.

The governor and the council reached out to William Travis for his opinions on the organization of an army for Texas’s defense. On December 3, Travis answered in a letter stressing the need for a cavalry commanded by a lieutenant colonel answering to the commander in chief, and suggested volunteers be subject to regular discipline and rules and articles of war. “A mob can do wonders in a sudden burst of patriotism or of passion, but cannot be depended on, as soldiers for a campaign,” he implored.

From December 5–9, Texan forces unsatisfied with Burleson’s hesitant leadership, attacked San Antonio under the leadership of Ben Milam and William Cooke. After street to street and house to house fighting, they drove the Mexican army out of town and into an old mission across the San Antonio River called The Alamo. General Cós surrendered on December 9. Burleson paroled him and his men allowing them to return to Mexico, thus ending the first stage of the Texas Revolution. Neither Houston, Bowie nor Travis participated in this fight.

After suffering a congressional defeat that summer, Davy Crockett returned home and told his wife, Elizabeth, “Well, Bet, I am beat and I’m off for Texas.” He wanted to move his whole family immediately, but his wife convinced him to proceed, look over the country and then decide if he wanted to make a home there for the family. On August 10, Crockett wrote to The (Washington) National Intelligencer (published on September 2), “I do believe Santa Ana’s [sic] Kingdom will be a paradise compared to this, in a few years.”

Davy held a festive barbecue before beginning his journey in the company of two neighbors and his nephew William Patton on the morning of November 1, 1835. His daughter Matilda described her father on the morning he left as “dressed in his hunting suit, wearing a coon skin cap.”

On November 10, Crockett and company arrived in Memphis, where he strolled the streets in relative anonymity. However, word of his arrival spread and a crowd of admirers, the curious and some old friends grew. By that night a movable party roared through Memphis’s streets and taverns. James B. Davis, a young man on the periphery of the group, described it as a “big bender,” adding, “It is needless to say we all got tight…very tight.”

Davy loosened up enough by morning to take leave of his beloved Tennessee for the last time. Crockett and his companions boarded a ferry, crossed the Mississippi River into Arkansas and made good time through the territory, arriving in Little Rock by the evening of November 12. There they attended a dinner in his honor, and he entertained with a speech. He and his party set out again the next morning. They crossed the Red River at Lost Prairie, Arkansas, setting foot in Texas for the first time. Before leaving Arkansas, with funds running low, he traded his pocket watch with its inscription of his motto, “Go Ahead” to settler Isaac Jones for his watch and a 30-dollar balance.

During the following month, the travelers roamed and explored the northeast Texas countryside, visiting Big Prairie, Clarksville and Nacogdoches. Crockett enjoyed celebrity treatment at each town and delivered his well-rehearsed speeches. He and his party became so enthralled during a hunting expedition in December that they went missing for several days, causing speculation that they had been killed by Indians, as later reported by American newspapers. It is unlikely that Crockett and his friends fully grasped the seriousness of the situation into which they rode.