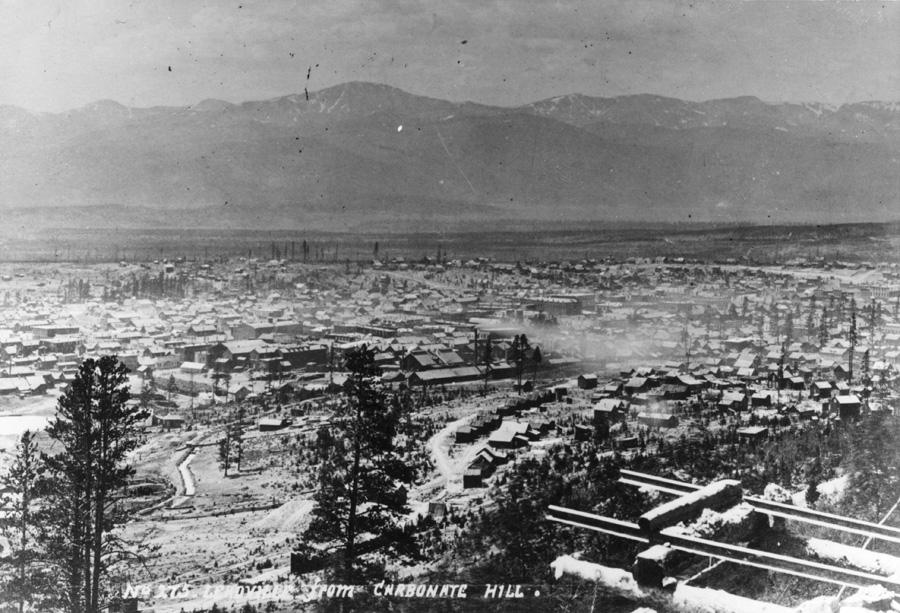

Leadville, Colorado, was the last place Doc Holliday needed to be the summer of 1882—its climate was deadly for a man suffering from tuberculosis; even the promotional literature for the region said so. “Persons troubled with weak lungs or heart disease should give the new camp a wide berth,” advised the Tourist’s Guide to Leadville and the Carbonate Fields. “The rare atmosphere accelerates the action of both these organs and unless they are in perfect condition, serious results may follow.”

Leadville, Colorado, was the last place Doc Holliday needed to be the summer of 1882—its climate was deadly for a man suffering from tuberculosis; even the promotional literature for the region said so. “Persons troubled with weak lungs or heart disease should give the new camp a wide berth,” advised the Tourist’s Guide to Leadville and the Carbonate Fields. “The rare atmosphere accelerates the action of both these organs and unless they are in perfect condition, serious results may follow.”

When Doc arrived in Colorado with Wyatt Earp and his posse following the vendetta ride against the Cow-boys of Cochise County, Arizona, Leadville was not his destination. Colorado was merely a staging point for his next move.

But as had often happened in his young life, Holliday’s plans were altered by circumstances. His arrest in Denver, and the attempt to extradite him back to Arizona for the murder of Frank Stilwell, gave him wide publicity. In Gunnison, where he visited Wyatt Earp after his release, he assured a local reporter that he was not traveling about the country in search of notoriety. By July 11, Doc was in Pueblo for a court appointment on the faked charges that had been used to prevent his extradition. His case was continued on July 18, 1882, and that same day, the Leadville Daily Herald announced that “Doc Holliday is visiting Leadville.”

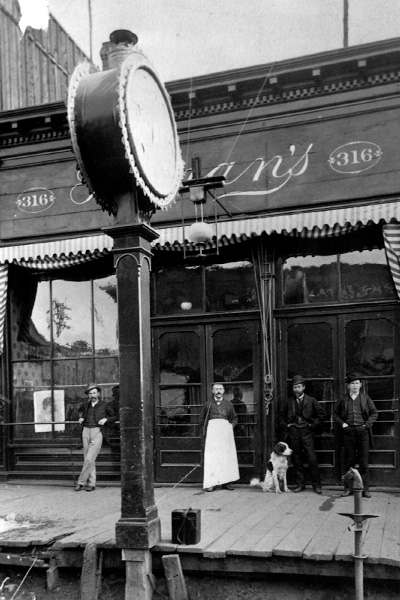

Leadville was a magnet for gamblers. The town’s boom had already peaked when Doc arrived, but there were still plenty of opportunities. Doc had friends there, too, in the business and mining community. There were acquaintances from the gambler’s circuit as well. It is fair to say that Doc fit in, and so he stayed. His reputation made him something of a celebrity, and he took a room at 106 East Second Street, finding work as a faro dealer at Cyrus Allen’s Monarch Saloon at 320 Harrison Street. With a little luck playing poker at upscale houses like the Board of Trade and the Texas House, Doc eventually took better quarters at 219 West Third.

At first, Cy Allen was pleased with the attention his new dealer attracted. Occasionally, Doc had to slip out of town for the ongoing legal wrangle at Pueblo, but by December, he was settled enough to be acknowledged as one of the principles in fighting the fire that destroyed Leadville’s most fashionable gambling hall, the Texas House.

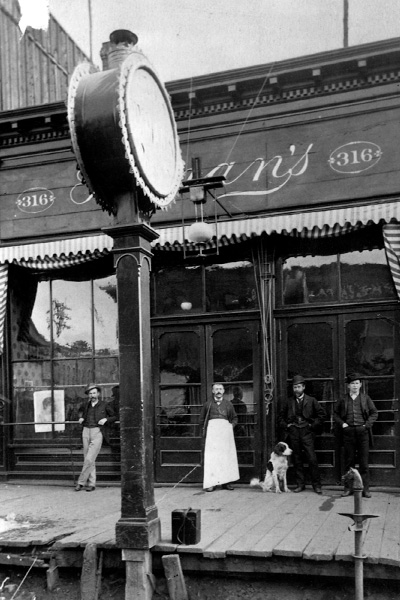

The Pueblo case was finally disposed of in April, 1883, and his immediate troubles seemed over. Unfortunately, Doc’s luck turned bad as the year proceeded. The predictions about Leadville’s climate proved all too true, and Doc, who had regained some of his youthful vigor in Arizona, began to feel the toll of his worsening tuberculosis. To add to his troubles, he fought recurring battles with pneumonia during the winter of 1883-84. As his health failed, he drank more and began to use laudanum. Doc was visibly in bad shape. His health was so bad that it affected his gaming skills as well, causing great concern among his friends. Discharged from the Monarch, Doc found work dealing at Mannie Hyman’s at 316 Harrison, two doors down. Hyman also allowed him to use a room at his place.

Then Doc learned, in October, that his cousin Mattie Holliday, the one person he had corresponded with regularly since leaving Georgia 10 years earlier, had entered a convent in Savannah. The effect of this can only be imagined since the true nature of the relationship between the two remains shrouded in mystery.

Moreover, Doc was already grappling with another problem. Not long after he arrived in Leadville, he discovered that Johnny Tyler, a man he had once humiliated in Tombstone, was dealing at the Casino Saloon nearby.

On the night of October 10, 1880, Doc and Tyler had quarreled at the Oriental Saloon in Tombstone. Doc’s later explanation that Tyler was trying to disrupt gambling in several of Tombstone’s saloons was confirmed early in 1881 when Wyatt Earp ejected Tyler from the Oriental for trying to disrupt play while Doc watched Tyler’s friends over the barrel of a drawn pistol.

Tyler left Tombstone, and by 1882 was a fixture in Leadville gambling houses. Tyler wasted no time renewing the rivalry after Doc arrived. There were other old Tombstoners there, and the old resentments from Arizona festered. The papers characterized the conflict as a dispute between the “Slopers,” gamblers from the Pacific Slope, and “Easterners,” presumably anyone from points east. Yet, at the center of the controversy stood Johnny Tyler and Doc Holliday. As a Leadville correspondent to the Tucson Citizen would put it later, “The old imbroglio was rankling in their breasts here, and Tyler and his friends did everything they could to prejudice the public against Holliday.”

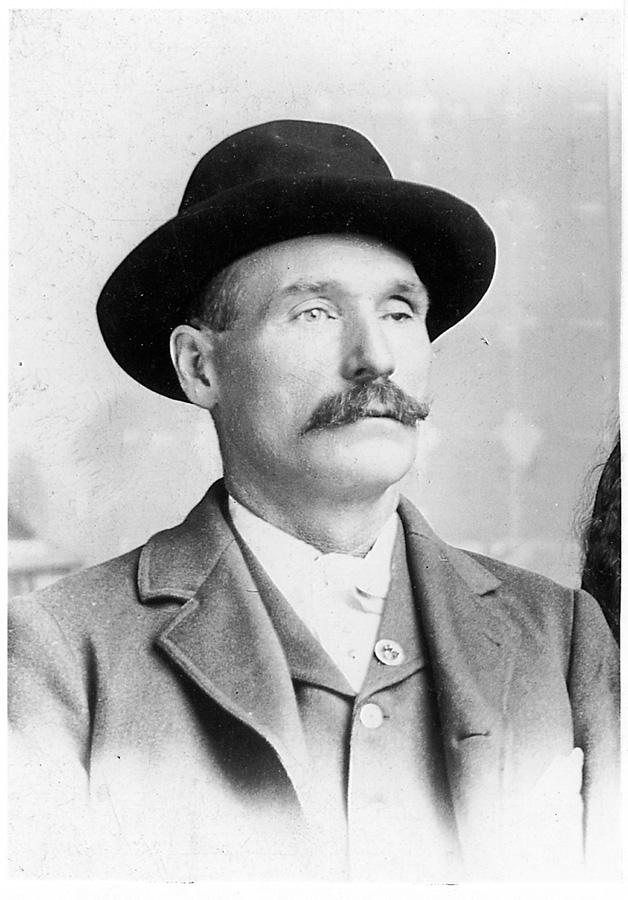

As 1884 proceeded, the controversy grew nastier and drew in a local named William J. “Billy” Allen, a former Leadville police officer and a bartender at Cy Allen’s place. He became a policeman in Leadville in 1880. Allen’s only connection to Tombstone was Johnny Tyler, now dealing at the Monarch, who apparently fed Allen plenty of information about Doc’s alleged bad character.

On July 23, 1884, the Tyler crowd tried to provoke a fight with Doc at Hyman’s. Doc walked away. The next day Doc, with “tears of rage coming to his eyes,” told a reporter for the Daily Democrat that they dared to do it because they knew he could not retaliate:

If I should kill some one here . . . no matter if I were acquitted the governor would be sure to turn me over to the Arizona authorities, and I would stand no show for life there at all. I am afraid to defend myself and these cowards kick me because they know I am down. I haven’t a cent, have few friends and they will murder me yet before they are done.

The reporter did not doubt him. Nor did most other folks. On August 24, the Carbonate Chronicle added its opinion about the disturbance at Hyman’s the previous day:

It looks very much as though a gang of would be bad men had put up a job to wipe Doc Holliday off the face of the earth. There is much to be said in favor of Holliday; he has never since his arrival here made any bad breaks or conducted himself in any other way than a quiet and peaceable manner. The other faction do not bear this sort of reputation.

Doc was a mere shadow of his former self. He was down to 122 pounds. His hand shook. His cough was debilitating. He was also so afraid that the slightest mistake on his part would cause him to be sent back to Arizona that he even stopped carrying a gun.

Doc was also broke—and that proved to be his undoing. He had borrowed five dollars from Billy Allen, which, as it turned out, was enough to provoke a fight. Billy had asked Doc for the money several times. On August 18, Allen called Holliday a “son-of-a-bitch” and threatened to “do him” the next time he saw him if he did not pay up. To Doc’s friends, his physical condition, his obvious hard luck, and the small amount of money involved, made Allen’s threat seem calculated to provoke a fight rather than to collect a debt. Several of Doc’s friends warned him to be on his guard.

After a long night, Doc retired near 5:00 a.m. on the morning of August 19, 1884. That afternoon, Billy Allen walked into Hyman’s, looked around, and left. About 3:00 p.m. Doc got up and went to Hyman’s. While Doc and Mannie were talking, Pat Sweeney, a gambler friend, interrupted them. Sweeney informed Doc that Allen was looking for him with a gun, “I think it is a six-shooter.” In front of witnesses, he told Doc that Allen had sworn that if Doc did not pay up, “he would knock him down and kick his d—-d brains out.” Doc remarked, with a few choice epithets, that there would have to be a fight and asked Sweeney to go to his room for his pistol. Sweeney refused.

One witness testified that Doc said, “I’ll go get the gun,” and that he left the saloon with Sweeney. They retired to the room which Holliday shared with Frank Lomeister, a bartender. Once there, Doc mellowed. He told Sweeney, “I don’t think it is right that one should be disarmed and another allowed to carry a gun; I don’t want to be murdered.” He seemed anxious to avoid a fight. Sweeney, Lomeister, and Doc then walked downstairs to Hyman’s where he told both men that he did not intend to be cooped up in the bar all day and asked them to find Marshal H. S. Faucett or Captain Edmond Bradbury of the police force, “for I want protection.” His friends left to find the marshal.

Doc also asked Mannie Hyman’s help to find the marshal, “as I would not carry a gun, for I had no money to pay a fine, and I did not want to be murdered.” Doc grew impatient and decided to look for the marshal himself. He was the first to find Faucett, in front of Sands & Pelton’s. He asked him if Allen was, in fact, a “special” policeman. Faucett told him that he was, but said he was authorized to carry a gun only in the saloon where he worked. Holliday threatened to get a shotgun to protect himself if steps were not taken. Faucett read the seriousness of the situation and told Doc that he would find Allen and put a stop to the matter before it got out of hand. The marshal immediately went to the Monarch but did not find Allen. Cy Allen (no relation to Billy) added his plea to end the matter quickly.

In the meantime, Doc found E. D. Cowen, a reporter for the Daily Democrat, who had helped Bat Masterson plead Doc’s case before the governor in 1882. “I wish you would do me a favor,” Doc said to him. “Bill Allen is after me. I want you to come around and see me wing him when the ball comes off. He isn’t worth killing.” Cowen declined, but with that announcement of intent, Doc returned to his room where he retrieved a revolver and had a friend take it to the saloon and place it behind the bar near the cigar case.

Near 5:00 p.m., Doc returned to Hyman’s to wait for the marshal, this time prepared for Billy Allen. While Doc waited, he stood beside the cigar case next to the bar where he could watch the entrance. His revolver was in easy reach.

He didn’t have long to wait. Allen had been looking for Doc. Shortly before 5:00, he had his boots polished and went to the Monarch to begin his shift, barely missing Marshal Faucett. He was behind the bar, when he saw Doc Holliday pass by en route to Hyman’s. He pulled off his apron, put on his coat and started for the door. Cy asked him where he was going. Billy replied, “I am going to hunt this party.”

“For God’s sake don’t go into Hyman’s,” Cy Allen responded, “as Holliday is in there.”

Allen had scarcely left when the marshal returned to the Monarch looking for him. Cy told him that Billy was on his way to Hyman’s. Outside Hyman’s, Patrick “Blackie” Lorden, an employee, watched Allen approach and warned Captain Bradbury, “If Allen puts his foot inside the door there will be trouble.” Bradbury had little time to react as Allen brusquely pushed by him, ignoring his warning.

As Allen stepped through the door, his hand in his pocket, Doc grabbed the revolver under the counter and fired. The first shot struck the window frame above Allen’s head. As Allen turned, he slipped and fell. While he tried to regain his footing, Doc fired again. Allen went down with a bullet in his arm below the shoulder that tore through the muscles and ripped open an artery. Henry Kellerman, a bartender, grabbed Doc as he tried to shoot again, and Bradbury sprang through the door shouting, “Doc, I want your gun!” Doc again asked for protection as he surrendered his gun and was led away.

During that reprieve, Allen stumbled out and collapsed in front of Dave May’s clothing store. Cy Allen, who had followed Billy from the Monarch, spirited him away to a doctor who stopped the bleeding and saved his life.

Immediately the question was raised, was Allen armed? He and other witnesses testified that he was not, but several swore he had his hand in his pocket, and at least two said they saw a gun. Doc seemed surprised when the Democrat’s reporter told him that they had found no gun, but he brushed the comment aside with the remark, “His friends spirited it away — that’s all.” He said he saw the butt of a revolver, and added, “Of course I couldn’t let him murder me so I fired.” Doc also insisted the affair was not over the five-dollar debt. “That was just a pretext,” he insisted. “It is the old trouble, and Allen was picked out as the man to kill me.”

Some locals agreed, and many expected the trouble not to end with the Allen shooting. One man predicted “the biggest free fight Leadville ever saw in one of the gambling houses.” He suggested that it did not matter whether the fight was over a “private grievance” or not, because Allen was a friend of the Tyler crowd, and they would use it as a pretext for going after Holliday. As for Doc, the informant said he would not cause any fight. “To do him justice, he isn’t trying to get up a fight, but is sick, and knows he has a hundred times the worst of it and would be glad if they would let him alone.”

Others derided predictions of further violence as “bosh of the worst sort.” One observer insisted that Allen would tell his friends to let the matter drop and even predicted that he would not press charges. What was true beyond a doubt was that the saloonkeepers and gambling house operators were anxious to prevent trouble and worked together to quell any thought of carrying the matter further.

Doc was arrested on a charge of “assault with intent to kill.” In Judge W. W. Old’s office on the afternoon of August 20, bail was set at $5,000, and John G. Morgan of the Board of Trade and Colonel Samuel Houston of the rebuilt Texas House signed his bond. A preliminary hearing was held on August 25, in a packed courtroom. On the stand, Doc tried to introduce the earlier troubles with the Tyler crowd, but the judge ruled that topic irrelevant, which may well have prevented the full truth about what happened from ever coming out.

Afterward, the Judge increased Doc’s bail to $8,000, and he was remanded to jail, creating an immediate concern for his health. The Chronicle observed, “Should Holliday be obliged to remain behind bars up to the day of his trial it would probably go very hard with him, as his constitution is badly broken and he has been really sick for a long time past.” Eventually, on September 6, the attorneys and bondsmen worked out a deal with the judge to release Holliday because of his poor health.

Trial was set for December. On September 9, the Democrat reported, “Doc Holliday expresses the utmost confidence over the result of his case. He is busy looking up testimony.” The weeks passed quietly as Doc worked with his attorneys on his defense. That fall, a report circulated in Arizona that Doc had shot a policeman named Kelly, but it was a confused account of the Allen shooting, and P. A. Kelly was still on the force in Leadville, unscathed. But on October 26, Doc inadvertently caused a small stir when he appeared at the train station to attend the High Line’s inaugural run as a section of the Union Pacific. He caused some consternation and considerable comment among passengers on an excursion train to Breckenridge, although the train departed on schedule and Doc was on his best behavior.

From the beginning though, public sentiment generally favored Doc, out of sympathy more than anything else. Over and over again, Doc’s good behavior in Leadville and the contrast of his physical condition to Allen’s were the topics of conversation. The Democrat in reporting the preliminary hearing argued that “public sentiment”

. . . which has nothing to do with the law, is largely in favor of Holliday. . . . Holliday has been, without doubt, an abused individual. The manlier class of the community appreciate this, but have little criticism to make as to his action in connection with his trouble with Allen, for whatever the latter’s intentions may have been, Holliday had reasons, whether or not they are good in law, for believing that past persecutions were to be concluded by a violent assault.

It was not that people thought Allen a part of a conspiracy. He was considered a decent man by most. After posturing with an air of righteous indignation against Doc’s “element,” Johnny Tyler and cronies quietly retreated from view. But Allen never relented in his determination to prosecute Doc.

In December, Judge George Goldthwaite granted a continuance and set trial for the spring term in 1885. The trial itself, which convened on March 27, 1885, was anti-climactic. The prosecution tried to make the case that Doc had threatened Allen and presented several witnesses who claimed Allen had been unarmed and only meant to talk to Doc. The defense was able to show that even some of the prosecution witnesses were sympathetic to Doc and built a strong case that if Allen was unarmed, the threats he had made justified Holliday’s action. On March 28, 1885, the jury deliberated only briefly before returning a verdict of not guilty.

Doc Holliday was not run out of Leadville. Some members of the Holliday family believe that Doc left town shortly afterward and met his father in New Orleans for a brief reunion. The story has a certain sentimental appeal but no clear evidence to support it. Whatever the case, he was back in Leadville by June, in time for an episode with a touch of irony in light of the Allen case.

A local gambler by the name of Harvey Rustin, alias Frank Miller, alias “Curly Mack,” owed Holliday $50. Curly Mack was a hardcase who had fled Leadville in 1882 after three men assaulted a big winner outside a gambling hall. He was arrested in Cheyenne, Wyoming, and returned to Colorado. Curly had beaten the charges and was back in the gambling rooms of Leadville. He had apparently owed the debt to Doc for some time when Doc collected it in an unusual way, according to the

Aspen Times of June 12, 1885:

Some nights ago, Curley [sic] was seated at a faro bank with a big stack of “reds” before him. Luck was with him and he made a winning of a hundred and fifty dollars. Holliday was standing behind him deeply interested in the game. Just as Curley was about to “cash in” his creditor stepped to one side so that Curley could see him, and drawing a six-shooter from the waistband of his pants he coolly remarked, “I’d like that fifty to-night Curley.” When the player looked up and saw the muzzle of the gun and the cold, hard face of “Doc” with its determined expression he shoved the whole pile of chips over and said, “take them all.” “Doc” counted out his fifty dollars and pushed the others back to the winner and walked out, and that settled it.

In October of 1885 street gossip revived talk of the old rivalry between Doc’s friends and the Tyler-Allen group and predicted the possibility of gunplay. P. A. Kelly, who had succeeded Faucett as marshal in May, kept both groups under close surveillance, and the talk never progressed to action. Johnny Tyler, who remained strangely mute through the whole Holliday-Allen affair, despite his role in stirring things up in the first place, remained in Leadville for a short time. Later, he reportedly left for Japan and vanished into obscurity.

Billy Allen remained in Leadville for a time before moving to Garfield County, where he served as a scout in the Ute Indian trouble of 1887. In 1898, he followed the gold rush to Alaska and was appointed a deputy U. S. marshal during the “clean-up” of Nome. As a federal officer he was involved in a lawsuit with Wyatt Earp. Ironically, it concerned a debt.

During the winter of 1885-86, Doc returned to Denver. For a time he enjoyed the opportunities and pleasures of the big city, and his luck seemed to return. In the spring of 1886, he traveled to Pueblo and eventually to Silverton where he was interviewed by a reporter of the New York Sun. The article, with heavy-handed editing, was published across the country, even in Doc’s home town of Valdosta, Georgia, where it caused quite a stir. Hidden in the purple prose, though, was Doc’s humor and his insistence that he was not a killer. “The claim I make is that some few of us are entitled to credit for what we have done,” he said. “We have been the forerunners of government. As soon as law and order was established we never had any trouble.” His elevated perception was not shared by Denver authorities when Doc returned to the city. Denver was “growing up.” The “sporting element” found itself under siege, and Doc felt the pressure along with the rest, perhaps more so because of his notoriety.

Holliday met Wyatt Earp for one last time that summer at the Windsor Hotel. They reminisced briefly and then embraced tearfully as Doc said, “Good-bye old friend . . . . It will be a long time before we meet again.” While in the mile-high city, Doc encountered another ghost from his past. One night on the street, he spotted Milt Joyce, another old adversary from Tombstone, and brushed against him as they passed. Later, Joyce decided that Doc’s action had been a challenge. He found Doc in a saloon and walked around him “to give him a chance if he wanted it.” Joyce recalled, “He didn’t look at all scared, but he wasn’t looking for any more trouble.”

His more affable demeanor was not enough to assuage police concerns, however. On August 4, 1886, following his arrest for vagrancy, the Denver police escorted him to the train station, where he caught the train to Leadville. He wintered there in 1886-87, working again for Mannie Hyman. The following May he departed for Glenwood Springs in a last desperate attempt to prolong his life. He died there on November 8, 1887. A Leadville paper remembered him fondly:

. . . whatever faults he had, there beat beneath his bosom the most generous impulses. There is scarcely one in the country who had acquired a greater notoriety than Doc Holliday, who enjoyed the reputation of being one of the most fearless men on the frontier, and whose devotion to his friends in the climax of the fiercest ordeal was inextinguishable. It was this, more than any other faculty, that secured for him the reverence of a large circle who were prepared on the shortest notice to rally to his relief . . . . A fellow of pleasing manner, and very polished in his address, his prematurely frosted looks attracted attention wherever he went. Here he played the cards and occasionally dealt from the mystic box, until he became involved in a series of complications after which he sought other camps.

The Billy Allen case dispelled two of the most common interpretations of Doc Holliday’s character and personality—that he wanted to die and that he was a mean-spirited, obnoxious drunk.

His conduct throughout his Leadville years revealed a man clinging tenaciously to life. Moreover, he received an astonishing amount of public support in a case in which his opponent was a local man who was respected and well liked in the community. There was none of the fatalism later writers would attribute to him, none of the brash temptation of death with other men that legend makers would later celebrate. Nor was there evidence in Leadville that he was a social pariah. In his last gunfight, he aroused more sympathy than disgust, more admiration for his fortitude than disdain for his weakness.

Doc Holliday’s situation after 1882 was touched by a tragic irony. For the first time in his life he had a “frontier wide” reputation, with both the respect and the fear such a reputation carried. Yet he seemed to prefer a life of quiet repose, as if the vendetta ride with Wyatt Earp in 1882, and his subsequent close call in Denver, had sobered him considerably. He appeared genuinely fearful that if he got into serious trouble in Colorado, he might yet be turned over to Arizona authorities, and that if he left Colorado, he would be pursued by Arizona officers. In a very real sense, then, Colorado became his prison.

The result was tragic. Once out of Arizona, Holliday’s health deteriorated rapidly so that his exile in Colorado became a death sentence. Arizona had given Doc a reprieve. His health had improved there, and some of that vigor he had once known returned, enough that he had ridden the vengeance trail after Morgan Earp’s killers without complaint. Now, in the thin air of the mountains of Colorado, the ravages of his disease regained control—its momentum accelerated. The Leadville years, though marked with courage, bore testimony to the wasting effects of the tuberculosis that tore at his will as well as his lungs. Against that enemy, Doc’s reputation meant nothing. Doc had finally met his match.

Gary L. Roberts, retired professor of history and specialist on violence in the American West, placed his first article with True West in 1961. Since then, he has published more than 75 articles in magazines, journals, and anthologies on the Old West. He is actively working on a biography of Doc Holliday, following a long collaboration with Susan McKey Thomas.

Photo Gallery

– Courtesy of the Denver Public Library Western Collection –

– Courtesy Regina Peck Andrus, great-grandaughter of William Allen –

– Photo by BBB –