Whether highborn or from the wrong side of the tracks, those who came West appreciated grit in a person, never mind if displayed by a hero or an outlaw. Their attention was captured by the grit displayed by the Marlow Brothers who overwhelmed a vigilante mob while shackled.

George, Charley, Alf and Epp Marlow were chained together in pairs along with two other prisoners as they were being transported out of Graham, Texas, in the dead of night on January 19, 1889. The brothers were accused of killing a popular local sheriff. They were being transported to a nearby town so they would not be lynched.

With Phlete Martin guarding them, they were in the lead wagon as they began crossing Dry Creek. A second wagon followed manned by Deputy U.S. Marshal Edward Johnson and three additional guards. A buggy with four guards brought up the rear.

As the first wagon entered the shallow creek to cross it, masked men came out of the brush shouting for the convoy to halt.

“Here they are,” shouted Martin diving off the first wagon. “Take all six of the sons of bitches!”

When Deputy Marshall Edward Johnson saw his guards run off to join the vigilantes, he began shooting at them, hitting one before taking a bullet himself through the hand. The one-armed Johnson, who lost his other hand years earlier in a gunfight, took cover.

The brothers along with the two other prisoners jumped to the second wagon where guns were kept. They could not run due to the shackles. Standing behind the wagons, the prisoners began shooting it out with the vigilantes.

They were able to kill vigilante leader Bruce Wheeler and one other. But Alf Marlow fell dead riddled with 15 bullet holes. Soon brother Epp was shot dead as well. George Marlow was hit in the hand but kept shooting as did the fourth brother, Charley. The two remaining brothers stood back-to-back answering shot for shot from the ambushing mob.

Someone fired a shotgun hitting Charley in the head and chest.

“Come again, you cowardly bastards!” George shouted. “We have plenty of ammunition and nobody hurt. Come on!”

Vigilante Frank Harrison then marched toward the Marlows, firing with his revolver. George shot him down. Charley spotted another vigilante shooting him down as well.

The vigilantes broke and ran. George and Charley were still cuffed to their dead brothers. George found a knife on one of the dead vigilantes using it to desperately cut the feet off the two deceased brothers thus allowing him and Charley to free themselves from the shackles.

The brothers, along with the other two prisoners, drove one of the wagons to the Marlow family cabin. On the way they stopped at a farmhouse to break their leg irons. One of the other prisoners went his own way while the other tagged along with the two brothers.

There at their family cabin they waited for the law to catch up to them.

It is the stuff of movies. Indeed, the story of Oklahoma’s Marlow Brothers became the John Wayne film The Sons of Katie Elder.

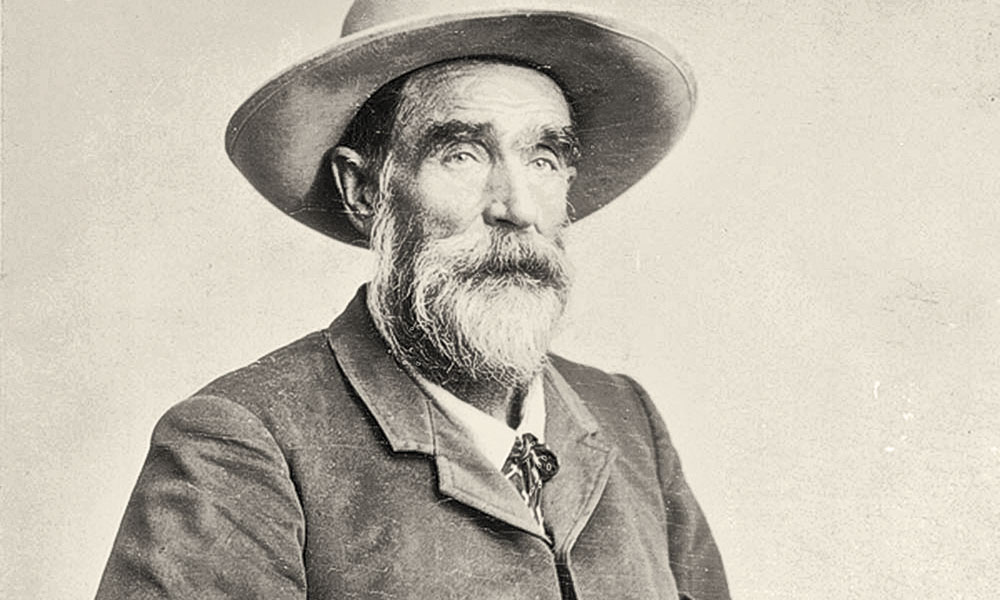

Their father, Dr. Williamson Marlow, suffered from wanderlust. As his family grew, he led them from Missouri to the Indian Territory into Mexico, New Mexico, Colorado and finally Texas. To make ends meet when he was not doctoring, he and his sons handled and sold stock, though there were rumors the animals had been rustled. The wandering claimed the elder Marlow’s first wife, but he found the time to obtain a second wife to be the mother to his sons. He died in Texas in 1885.

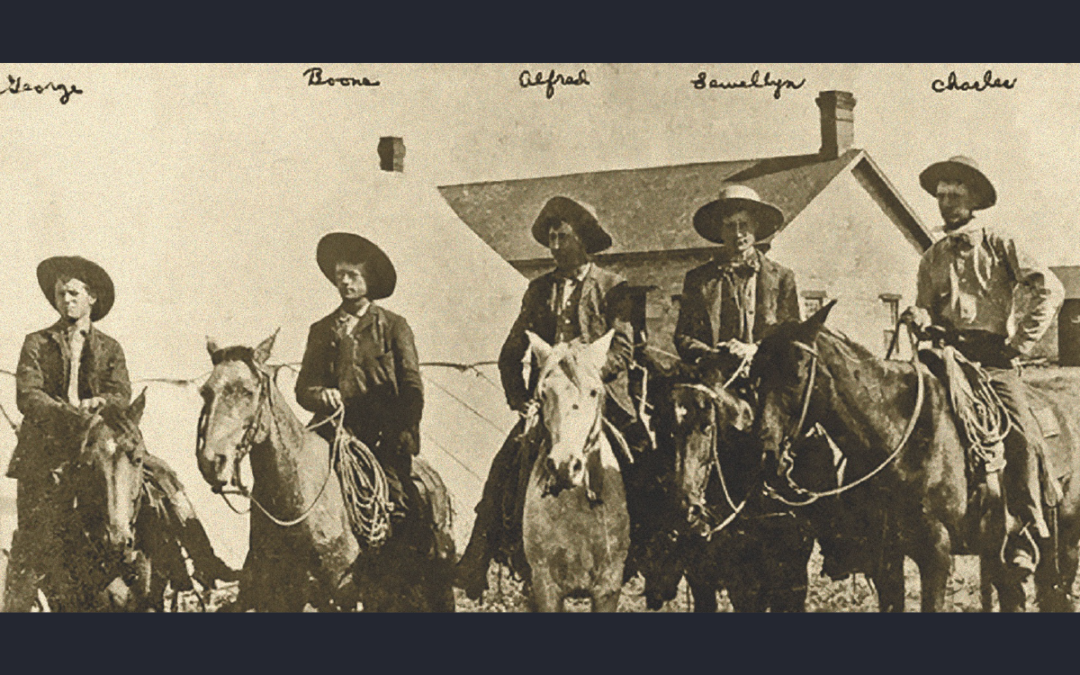

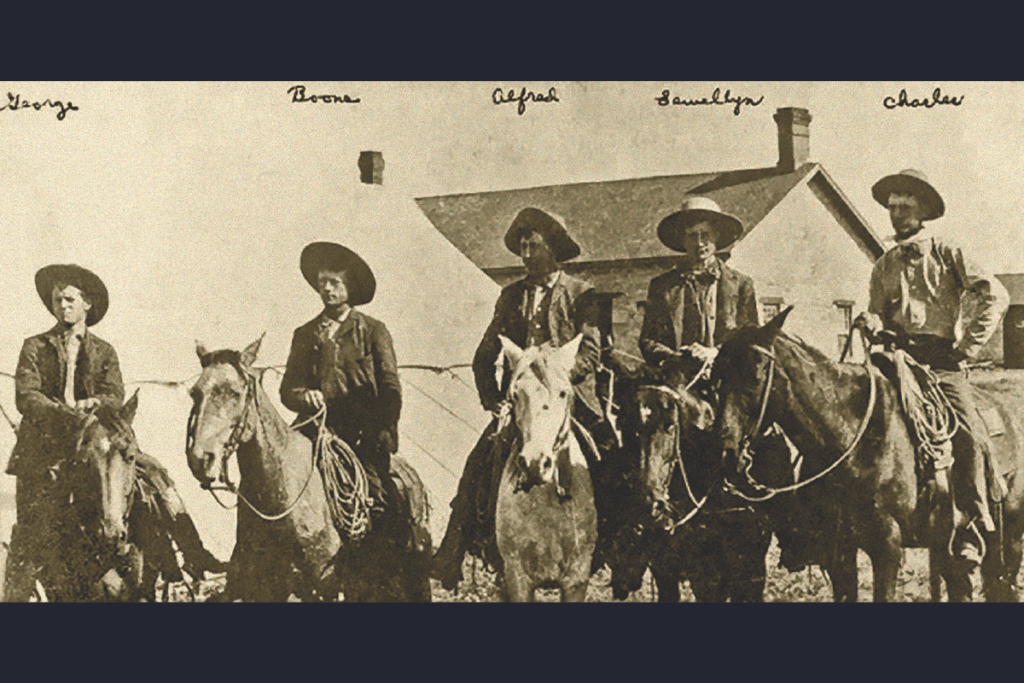

The second wife, Martha Jane, and sons George, Charley, Alf, Boone and Epp migrated across north Texas like nomads from one settlement to another.

Near the end of 1885, brother Boone shot and killed a cowboy in Vernon, Texas. He fled to Colorado. A court dismissed the murder charge against him on the grounds of self-defense. The Marlow family followed after Boone, reuniting in Trinidad, Colorado.

From there, the family started up a homestead in Indian Territory along the Chisholm Trail.

The family made a living selling horses to the U.S. Army located at Fort Sill. Texan drovers complained horses and some cattle being sold by the Marlows were actually from their trail herds as they drove to Kansas railheads. But Texas authorities had no jurisdiction in the Indian Territory.

By 1888, both Charley and Alf were married and fathers. They were working for a Kiowa chief named Sun Boy close to Fort Sill, while the other brothers were still working horses and cattle.

Come that spring, Charley rode to Gunnison, Colorado, to visit his friend Cyrus Shores, who was county sheriff, and his in-laws. But toward the end of summer, Las Animas County Sheriff William Burns wrote to Deputy U.S. Marshal Edward Johnson serving in Graham, Texas, to watch out “for five Marlow brothers who are endeavoring to get away with 40 head of horses stolen from this place.”

Burns sent a follow-up letter stating the accusations against the Marlows had been a mistake. Still, between the Colorado letter and complaints that the brothers were also stealing reservation horses from American Indian owners, Johnson felt he had enough cause to form a posse and ride into the Indian Territory to arrest the brothers. Charley, Alf, Boone and Epp were cuffed and brought back to Graham for arraignment.

George gathered up the rest of the family and traveled to Graham to see if he could get his brothers released. The family rented a cabin near Graham, but when George went to the Graham jail, he found himself also arrested and jailed with his siblings.

A Texas grand jury indicted them on horse theft involving three Indians. None of the Indians in question testified against the brothers. “Marlow men no steal Indian man’s horses anyway because the Marlows had better horse,” stated Ba-Sinda-Bar, a Caddo who was one of the three supposedly aggrieved Indians.

Their stepmother was able to bail the brothers out in October.

Believing they would be found innocent, the brothers found jobs in the area. Meanwhile, Johnson was able to get a warrant against Boone on murder for the Vernon, Texas, shooting years earlier.

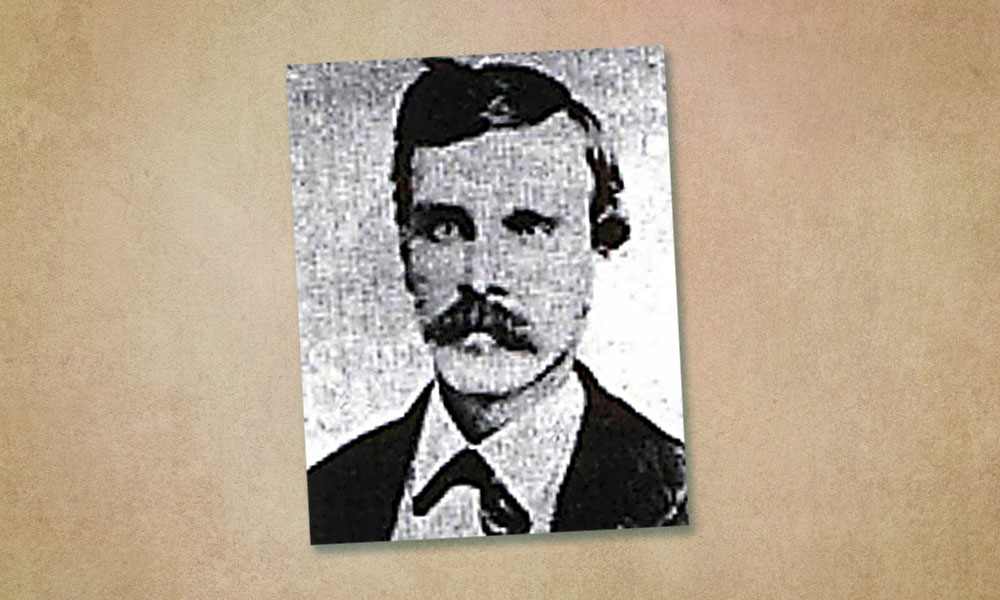

The Marlows did have a champion in Young County Sheriff Marion Wallace. Wallace and Johnson did not like each other, but Wallace was popular in the surrounding communities. It was Wallace who warned the family about Johnson.

When the warrant for Boone’s arrest arrived from Vernon, Wallace and Deputy Tom Collier rode out to the Marlow cabin to take Boone in. Collier went to the door first greeted by Charley who invited him in for dinner. The deputy stepped inside. Seeing Boone, Collier said. “I’ve come for you, Boone” then drew and fired his pistol at Boone but missed. Boone grabbed his Winchester and returned fire. One bullet grazed Collier, but a second shot struck Wallace in his side, mortally wounding him.

Epp rode into town to get a doctor. For some reason Collier began telling people arriving at the cabin it had been Charley who had shot Wallace, though the sheriff told the doctor it had been Boone.

Boone leaped on a mount and escaped into the Indian Territory. Though miles away when the shooting took place, George and Alf were arrested as were Charley and Epp as accomplices to the shooting. Bail was set at $1,000 apiece. Wallace died on Christmas Eve which made Collier the new sheriff.

After overhearing their jailers talk about lynching them, the brothers decided to try to break out. Getting a knife from another prisoner, they cut their way through the wall of their cell. On January 4, 1889, they managed to escape but were caught and shackled to each other before being placed back in a cell.

Two weeks later, on January 17, a mob broke into the jail. The jailer let the vigilantes into the cell. The mob tried dragging the brothers out, but they were putting up a fight. One man, Bob Hill, rushed in and grabbed Charley, but the Marlow brother gave Hill a beating. Hill struck his head against a wall, later dying from the injury. Alf drove the others out with a lead pipe he was able to get his hands on. The mob finally gave up and dispersed.

Johnson decided to spirit the brothers and the two other prisoners out the night of January 19, 1888, to Weatherford, Texas, and into the ambush at Dry Creek.

After escaping the vigilante ambush, the two brothers woke to find their cabin surrounded by Collier and his posse. They declared they would only surrender to a U.S. Marshal. For two days, the posse laid siege to the cabin when the U.S. Marshal finally arrived and took them away to safety, though in custody.

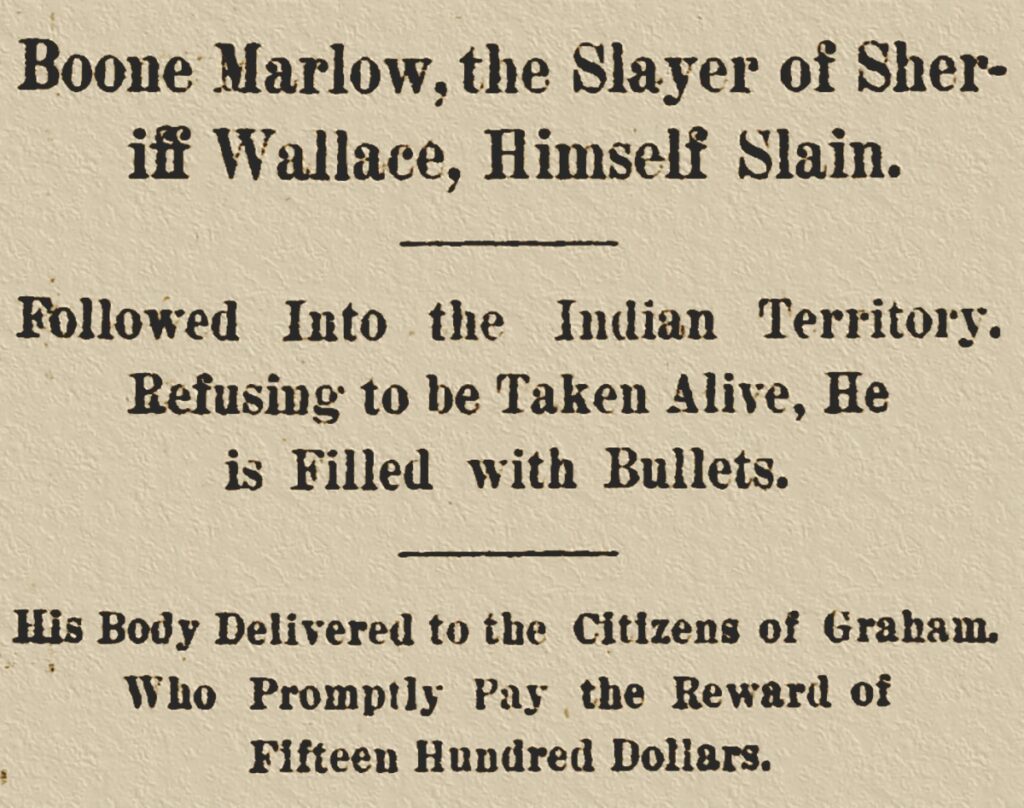

Their brother Boone was not so lucky. He had a reward on his head of $1,500 when his body was brought in riddled with bullets on January 29, 1889. Bounty hunters claimed he resisted arrest, but it was discovered he had been poisoned, and the bounty hunters were taken prisoner.

Graham citizens were shocked by the brutal ambush indicting several members of the vigilantes. Their trial date was set for October. George and Charley were acquitted of horse theft in March but told to stay in Dallas as federal witnesses for the upcoming mob trial.

But Charley got wind that Collier had a warrant for his arrest regarding the murder of Sheriff Wallace. The Marlows skipped out of Dallas, making their way to Ridgway, Colorado.

Texas Governor Big Jim Hogg issued an arrest warrant for the brothers on May 22, 1891, sending legendary Texas Ranger Captain Bill McDonald and another Ranger to bring them in from Colorado. But neither local law officers nor the townspeople would allow the Rangers to take the Marlows back to Texas.

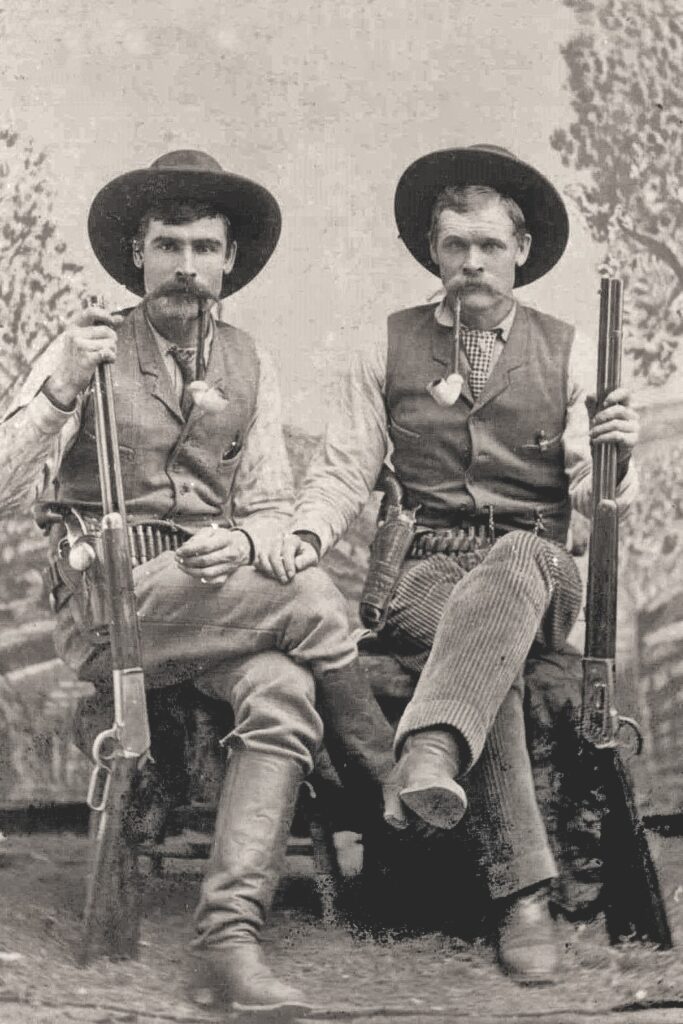

To avoid gunplay, the parties agreed the Marlows would remain federal witnesses in the case of the mob trial and be allowed to stay in Colorado. The two became successful ranchers and later became Colorado lawmen themselves.

In 1891, during sentencing of one of the mob members, Federal Judge A.P. McCormick stated, “This is the first time in the annals of history where unarmed prisoners, shackled together, ever repelled a mob. Such cool courage that preferred to fight against such odds and die, if at all, in glorious battle rather than die ignominiously by a frenzied mob, deserves to be commemorated in song and story.”

Mike Coppock grew up in Western Oklahoma and graduated from the region’s Phillips University with a degree in history. He has spent 40 years in Alaska as a newspaper editor, a teacher in a Native village, and a flight specialist. He is currently an interpretive coach at Denali National Park. In 2024, he won the Will Rogers Medalion Award for Best nonfiction article and his book, The Oceanside History of Alaska, was released.