Day after day, week after week, we went through the same weary routine of breaking camp at daybreak, yoking the oxen, cooking our meagre rations over a fire of sage-brush and scrub-oak; packing up again, coffee-pot and camp-kettle; washing our scanty wardrobe in the little streams we crossed; striking camp again at sunset, or later if wood and water were scarce.

Day after day, week after week, we went through the same weary routine of breaking camp at daybreak, yoking the oxen, cooking our meagre rations over a fire of sage-brush and scrub-oak; packing up again, coffee-pot and camp-kettle; washing our scanty wardrobe in the little streams we crossed; striking camp again at sunset, or later if wood and water were scarce.

—Luzena Stanley Wilson, 1849

Beginning in 1843 when the first major emigrant wagon train crossed the Oregon Trail, the routine was much the same as that experienced by Luzena Wilson.

Following a route blazed by Indians, mountain men eventually proved the feasibility of using wagons on the Oregon Trail. Women made the crossing in 1835 as Narcissa Whitman and Eliza Spalding traveled with their missionary husbands.

But it was the wagon train of 1843, with Jesse Applegate and Marcus Whitman (Narcissa’s husband made several crossings), that marked the true beginning of the Oregon Trail. The route crossed six modern states: Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho and Oregon. At that time the land was primarily Indian country and the Oregon Territory.

If you have two or three weeks, you can follow the entire Oregon Trail, but if you have only a week, begin your trip at Scotts Bluff in western Nebraska and follow the tracks of the pioneers across Wyoming to Fort Hall, Idaho. You’ll see some of the best remaining trail ruts and sites of the entire 2,000-mile journey. These days about half the trail remains intact, and of that amount the longest stretches are in Wyoming. Even better, most of the Wyoming portion is on public land, making it highly accessible.

Recognition of the trail’s sesquicentennial in 1993 led to increased efforts to mark the route, so you’ll find signs along the highways that will help keep you on course. Further, the Oregon-California Trails Association has worked diligently for years to mark the trail, placing hundreds of white carsonite markers on the actual route.

Scotts Bluff, Nebraska

Almost every traveler on the Oregon Trail—or Great Platte River Road as it’s been called by the historian Merrill Mattes—mentioned the inverted funnel-shaped sandstone outcrop known as Chimney Rock, a landmark that you can see from the top of Scotts Bluff. Chimney Rock, Court House Rock, Jail Rock and Scotts Bluff were the first prominent landmarks seen by Oregon-bound emigrants who had rolled their wagons 596 miles before reaching the point where mountain man Hiram Scott died in 1828.

Today, Scotts Bluff is a National Monument. You can drive a winding road to the top for views of the town of Scottsbluff (toward Chimney Rock) or the Western Plain. But the real attraction is the visitor center’s collection of original drawings by William Henry Jackson, depicting crossing the trail. They’re not only stunning, but they also show all of the major trail landmarks and conditions of the route to Oregon.

From Scotts Bluff, “head west young man” (or woman) to Fort Laramie, the most important site along the trail and one of three provisioning points available to the 1843 travelers. Near the Wyoming-Nebraska border, you’ll pass the site of the 1851 Horse Creek Treaty. This is where federal authorities negotiated with the Plains Indians, allowing the Oregon Trail to cross their country.

Fort Laramie, Wyoming

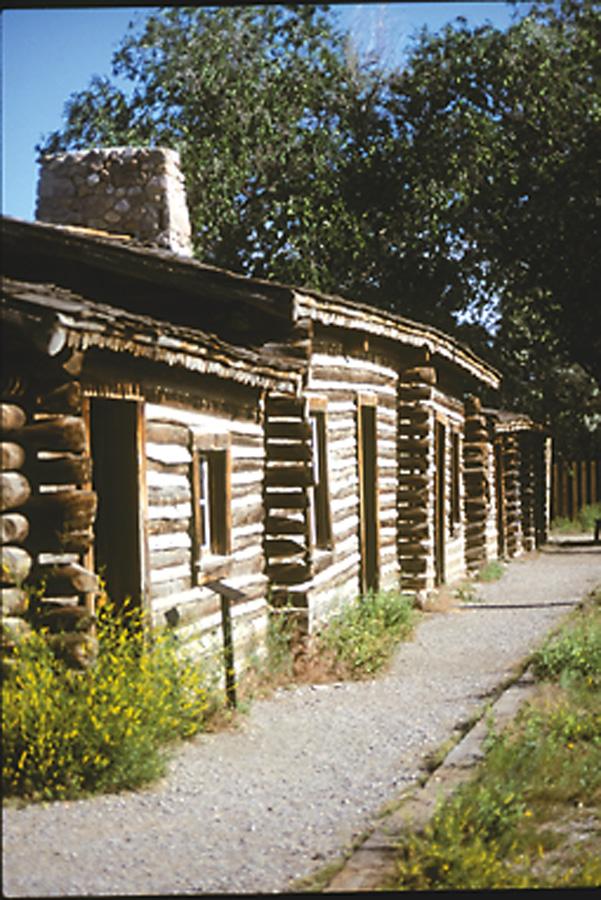

Started as a fur trading post in 1834, Fort Laramie operated as a trade site under the names Fort William, Fort Lucien and, finally, Fort John, though it was known unofficially as the Fort on the Laramie. In 1849, Fort John was purchased by the U. S. Army for $4,000 and officially named Fort Laramie. Troops were needed to provide protection for travelers on the trail (including Mormons heading to Deseret—Utah—and argonauts enroute to California’s gold fields).

Today Fort Laramie is a National Historic Site and the best man-made landmark along the Oregon Trail—some of the buildings that were standing when emigrants stopped there are still in use. Fort Laramie’s National Park guides can interpret the history of the various groups that ranged across America’s great central prairie.

Walk through the grass and beside the ruins of the post hospital and you’re in the ruts of the Oregon Trail. As you drive west, if you don’t mind a few miles of gravel road, take the back route to Guernsey and watch for the OCTA carsonite signs, marking the trail.

The signature ruts of the Oregon Trail are just west of Guernsey, where they cut through sandstone on a hillside above the North Platte River. Register Cliff, a sandstone wall where emigrants scratched their names, is also nearby.

Gravesites and trail points dot the route as it continues west toward Casper (U.S. 26 and Interstate 25). You can take a side trip to Ayres Rock, a natural bridge over LaPrele Creek. This idyllic setting is a contrast of red sandstone and green grass, so have a picnic and cool your feet in the creek. Not all emigrants saw the natural bridge be-cause the trail doesn’t pass by it, but many detoured to take in the view.

North Platte Crossing,

Casper, Wyoming

Today we bid farewell to the Platt which from here presents a strikingly picturesque appearance. We have followed its windings more than [700] miles, & are loth to part with it. We could always see its waters glistening in the sun as it flowed so quietly by our side.

With those words Harriet Talcott Buckingham in 1851 captured the feeling of most emigrants as they reached what is now Casper, Wyoming.

There were fords, ferries and eventually bridges across the North Platte in the few miles above and below present-day Casper. It was a natural crossing point for Indian trails, just as it was for the emigrant trails. It is the only place where the Oregon, California, Mormon, Bozeman and Pony Express Trails come together.

Located on the hill above town, the National Historic Trails Center (opening this year) interprets these major routes. Trail ruts lead through the sandy hills to the Center’s front door and away again toward the west.

Interactive exhibits, including a wagon that bumps and rocks as you watch a film about a river crossing, are part of the attraction. The Orientation Theater boasts a 55-foot-wide movie screen where you’ll see footage of wagons rolling along the trail in Wyoming. There is also a room devoted to the history of the Mormon handcart pioneers who became stranded in Wyoming’s snows in 1856.

When in the city, don’t miss Fort Caspar, a recreation of the post established at the site of the Platte Bridge and near where the 1865 Battle of Platte Bridge occurred. During that fight Lieutenant Caspar Collins lost his life, but his name remains. The city is also named for him, but is spelled Casper.

West of Casper, you can really get a feel for the trail—there are miles of route and ruts on public lands. Take Highway 220 for the paved version, or pick up a map at Fort Caspar to follow the actual route through the Avenue of Rocks, past Willow Springs to Independence Rock.

Independence Rock

to South Pass, Wyoming

Just as they did about Chimney Rock, almost every traveler on the trail wrote about Independence Rock, a granite outcrop 60 miles west of Casper that looks like a turtle.

This rock is covered with names, with great difficulty I found a place to cut mine.

—Sallie Hester, 1849

You can climb the granite outcrop (leave your cowboy boots in the car and put on something with rubber soles) and see the original carvings. From the top, look east and follow the trail as it snakes its way toward the Saleratus Lakes, or peer west and view the trail swales as they mark the sagebrush-covered land to Devil’s Gate, which is clearly visible.

On top of the rock the wind will likely keep the mosquitoes at bay, but around its base (where you can also see many carved names) those little buggers can be frightful.

Had an awful time fighting mosquitoes last night. Built a smudge and drove myself out of the tent instead of the mosquitoes.

—Alden Brooks, 1859

Most pioneer journals have some reference to mosquitoes. The insects even helped relieve the monotony of the trail. William Kelly used them in 1849:

During the bath, a most original wager was made betwixt two young fellows; that one should remain exposed without his clothes longer tha[n] the other, each acquiescing in the use of cigars; so, after lighting them down they lay on the bank, contiguous to each other, wincing as a sting was inflected on a tender quarter, and smoking with a fiercer energy as the pain became excessive. Both held out manfully for five minutes, when (Guy), in the act of giving up the contest, playfully touched the rear of his adversary with the end of his cigar, causing him to jump up in agony, swearing he “could not stand it any longer for the father of the flock had stabbed him.”

Beyond Independence Rock, you’ll pass Devil’s Gate, Split Rock and South Pass. The emigrant roads followed the route they did because of three major components: grade, grass and water. Along here the rise to the summit of the Continental Divide was gradual; there was good water in the Sweetwater River, and people generally found adequate grass for their animals.

When the emigrants reached the pass, they had achieved one milestone.

Today we set foot in Oregon Territory, the land of promise.

—Theodore Talbot, 1843.

But it wasn’t utopia, for he added,

As of yet it only promises an increased supply of wormwood and sand.

Fort Bridger, Wyoming

The Oregon Trail had a myriad of differing routes and cutoffs, but the main branch (Wyoming Highway 28) headed west then southwest after crossing South Pass, to the trading post mountain man Jim Bridger and his partner Louis Vasquez built “in the path of the emigrants.” Opened in 1843, the fort initially served emigrants, but fell under control of the Mormons from 1853 to 1857, and then became a military post until 1890.

This is a trading fort owned by Bridger and Bascus (Vasquez). It is built of poles and daubed with mud; it is a shabby concern. They have a good supply of robes, dressed deer, elk and antelope skins, coats, pants, moccasins, and other Indian fixens, which they trade low for flour, pork, powder, lead, blankets, butcher-knives, spirits, hats, ready made clothes, coffee, sugar, etc.

—Emigrant Joel Palmer, 1845.

Bridger’s original stockaded trading post has been rebuilt and a modern-day trader is on hand during the summer to sell you frontier-era goods. Now a Wyoming State Historic Site, Fort Bridger also has interpreters to provide details about the Mormon and military occupation. The site recalls its mountain man heritage every Labor Day weekend when the Fort Bridger Rendezvous takes place on its grounds.

Fort Hall, Idaho

From Fort Bridger, the Oregon Trail turns toward the northwest (follow Wyoming 412 to Kemmerer then head west on U.S. 30) and the trail’s third major fort. Fort Hall, like Forts Laramie and Bridger, owed its existence to fur traders. Nathaniel J. Wyeth erected the stockaded trading post in 1834 beside the Snake River. It was sold to the Hudson’s Bay Company in 1837 and was rebuilt a year later. After 1849 the post served emigrants almost exclusively until it was abandoned in 1856 due to Indian hostilities.

Like Fort Laramie and Fort Bridger, Fort Hall was an important place to stop and “recruit,” or rest and stock up on supplies. Though in 1843 John Boardman noted,

there was neither eat, nor flour nor rice to be had. Nothing but sugar and coffee at 50 cents per pint.

There is nothing left of the original Fort Hall, but the post has been recreated in Pocatello, Idaho, and you can take a tour or visit with interpreters.

Traveling the Trail

by Wagon

OK, you can drive your vehicle along existing roads and parallel the Oregon Trail, but I prefer going by wagon. In 1993, to report on the Oregon Trail Sesquicentennial, I traveled with a wagon train over portions of the trail in Nebraska, Wyoming, Idaho and Oregon. Since then I’ve traveled many more miles by wagon on the Mormon, California and Pony Express Trails, which follow the same basic route.

Moving behind a couple of mules traveling four miles per hour gives you lots of time to see the landscape. In places, particularly in western Wyoming, the terrain hasn’t changed much in the past 150 years. Though there are many variations to the Oregon Trail, in general it followed one trail corridor through Wyoming, basically along the North Platte River to Casper, then cross-country to the Sweetwater River, up it to South Pass and on across the Red Desert to Fort Bridger.

In my journal, which is a part of the book Wagon Wheels: A Contemporary Journey on the Oregon Trail that I co-authored with Ben Kern, I wrote on July 20, 1993: “The wagons lined out of camp and a brisk breeze hit us in the face as we made the fourth crossing of the Sweetwater River. Just before lunch we headed up our first hill where we saw the clear swale of an old trail angling up a draw and over the rise. It is probably a route once used by freighters going to Atlantic City. The Rocky Ridge trail lay about three miles east of our route and the old emigrant trail ran even farther east on the Sweetwater itself.”

July 22, 1993, I wrote: “It was very cold when we pulled out of South Pass City. The water buckets had ice on them. The wind washed off the snow-covered Wind River Mountains to the north.”

July 23, 1993, I wrote: “It rained most of the night. As the wagons pulled away from Pacific Springs, the sky lay heavy, the clouds just barely above the dirty, once-white canvas wagon coverings. The temperature dropped and clouds hugged the Wind Rivers. We pulled blankets and tarps around us to remain somewhat dry as misty rain turned the trail sloppy. We had a view of sage, bitterbrush and four remarkable sets of parallel ruts. I found myself counting the landmarks I’d passed: Rock Creek Station, California Hill, Chimney Rock, Independence Rock, Split Rock, Ice Slough, Rocky Ridge, South Pass, Pacific Springs, Plume Rock. I thought of those landmarks still ahead on the road to Oregon.”

As long as I can find a team and wagon heading out across one of the great trails of the West, I’ll go along. I spent time out on the Bozeman Trail in 2001 and this summer I’ll begin a trek over the South Branch of the Cherokee Trail from Fort Bridger to Bent’s Old Fort in Colorado. The Cherokee Trail crossing will cover 100-mile segments over the next several years, so grab your bonnet or hitch up your team and join me on the trail.

Candy Moulton is the author of Roadside History of Wyoming.