Billy The Kid

It all starts with that only known photo of Billy the Kid. He is standing there with a rifle, right? That’s what everyone’s seen from the start—old newspaper clippings, whatever. But even when that photo was first taken, they doctored it. Tried to fix it right out of the gate. They botched it. It was badly done. So instead of seeing this smart little Irish kid, America saw a moron.

And that’s what stuck. “Dirty little Billy killer.” And “Look at him—he’s a moron.” Well, that was total B.S. Nothing could be further from the truth. So, right then I thought, oh my God, an entire country got fed this false picture. Doesn’t matter if it’s important or not—it’s American history. Western history. It’s valid. You don’t have to be proud of it, but it’s there. And that kid was not a moron. So, I got into it. Read everything I could.

Turns out that Billy was really likable.

A good-looking young Irish kid.

There was this whole other side nobody talks about. All the Mexicans held him in high esteem—he was their guy—a folk hero—and none of that shows up. It’s just, “Oh, he was some dirty outlaw.” So that got me thinking: what was he really like? Why’d he become who he was? And all those little misfortunes and accidents—niche things that shaped the guy. That’s what intrigued me and that’s what set me out on this path.

—Buckeye Blake

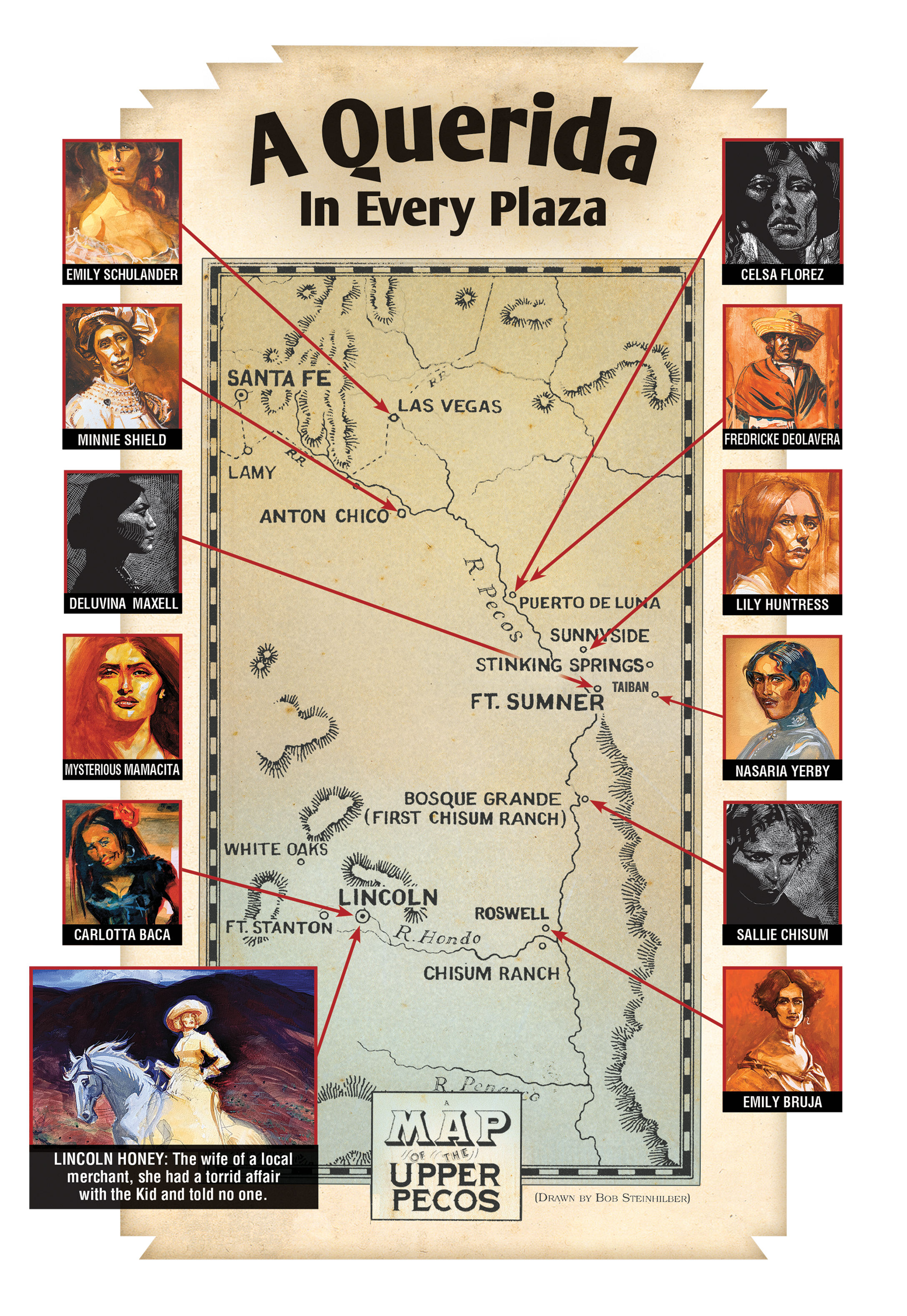

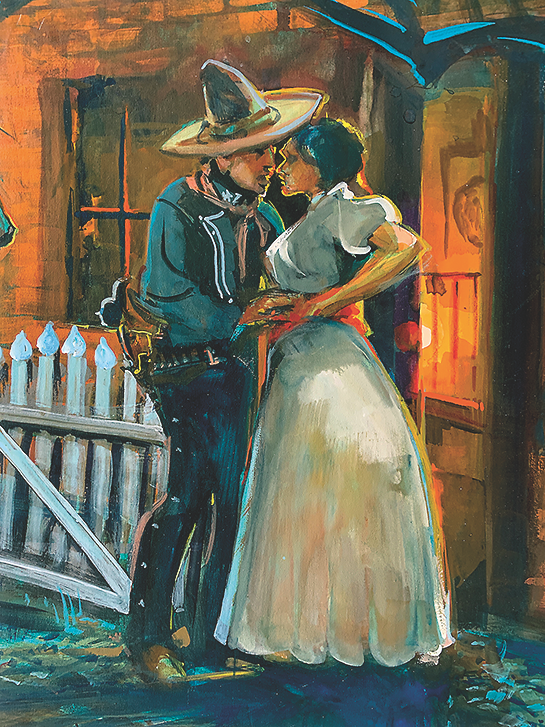

CHARMING BILLY

In 1924, Paulita Maxwell told writer Walter Noble Burns, “Billy the Kid, I may tell you, fascinated many women. In every placeta [little plaza] in the Pecos some little senorita was proud to be known as his querida [Spanish for beloved]. Three girls at least in Fort Sumner were mad about him. One is now a respected matron of Las Vegas. Another, who died long ago, had a daughter who lived to be eight years old and whose striking resemblance to the famous outlaw filled her mother’s heart with pride. The third was his inamorata when he was killled.” [She implies this unnamed lover was Celsa Gutierrez, but some historians believe Billy’s last love was, in fact, Paulita herself.] She goes on, “The weekly dance was an event, and pretty girls from Santa Rosa, Puerto de Luna, Anton Chico, and from towns and ranches 50 miles away, drove in to attend it. Billy the Kid cut quite a gallant figure at these affairs. He was not handsome but he had a certain sort of boyish good looks. He was always smiling and good-natured and very polite and danced remarkably well, and the little Mexican beauties made eyes at him from behind their fans and used all their coquetries to capture him and were very vain of his attentions… They knew how to use their black eyes to good advantage…[and made] their fans talk when their tongues were silent.”

SPOTTING BILLY

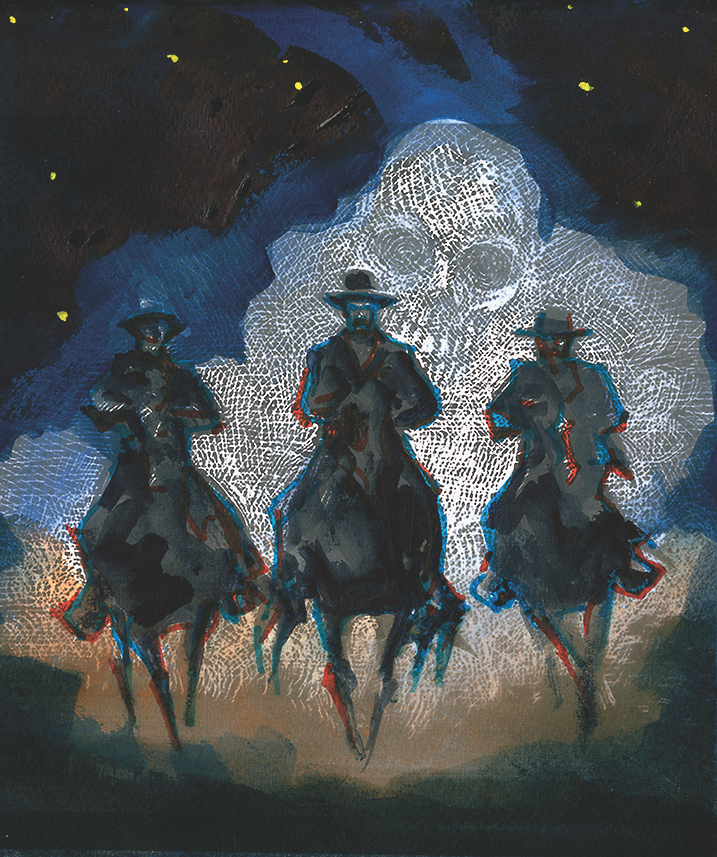

The Midnight Men

Sheriff Pat Garrett and two deputies leave Roswell, New Mexico, after dark on July 10, 1881. They take the back trails and ride all night. Scouting around the Old Fort Sumner area and finding nothing, they finally slip silently onto Pete Maxwell’s south porch on the old parade ground. The sheriff leaves his two deputies outside by the gate and goes inside to query Pete about the whereabouts of Billy the Kid. A full moon lights up the cottonwoods as a dark figure slips into the side yard and walks towards Maxwell’s buttoning his trousers.

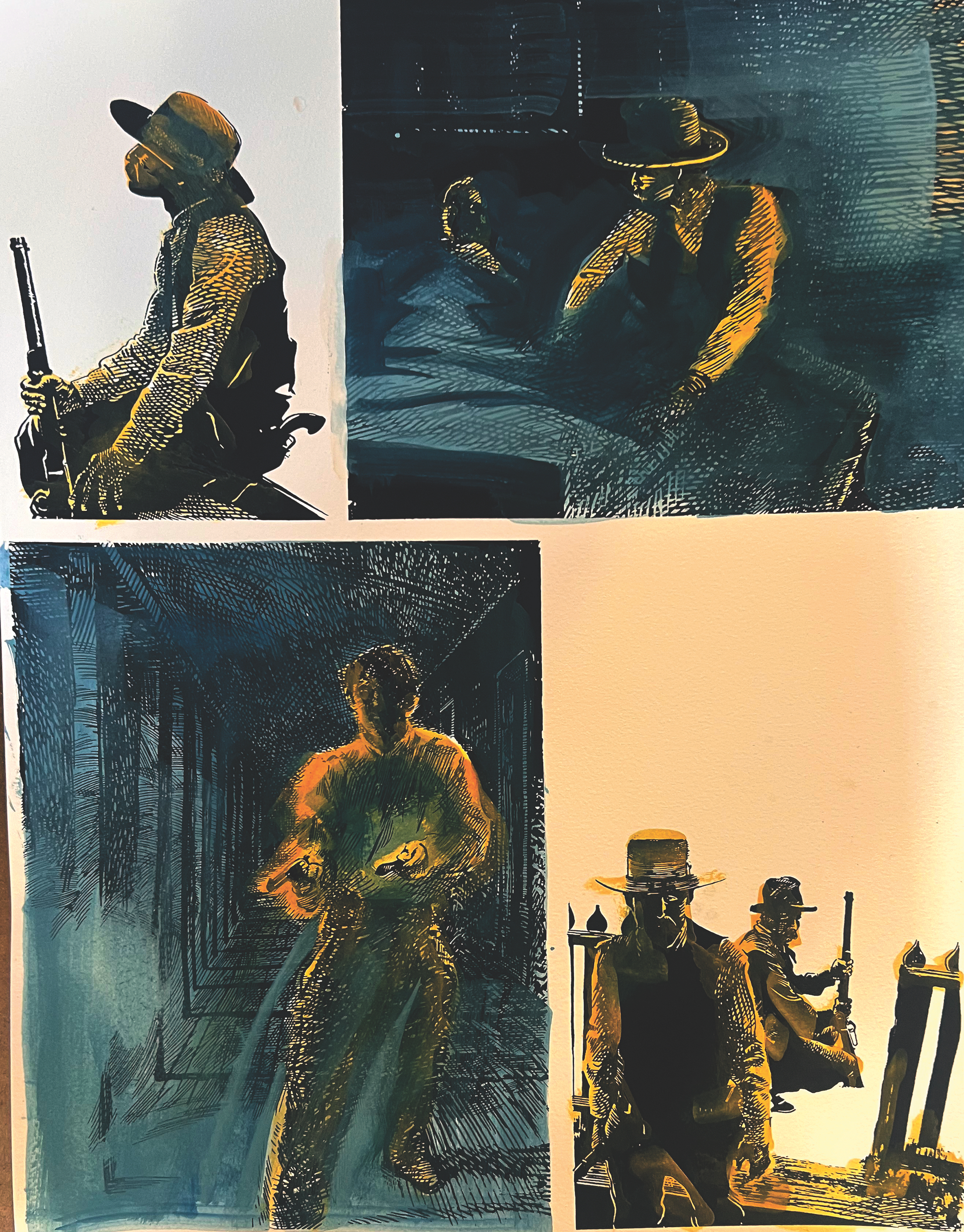

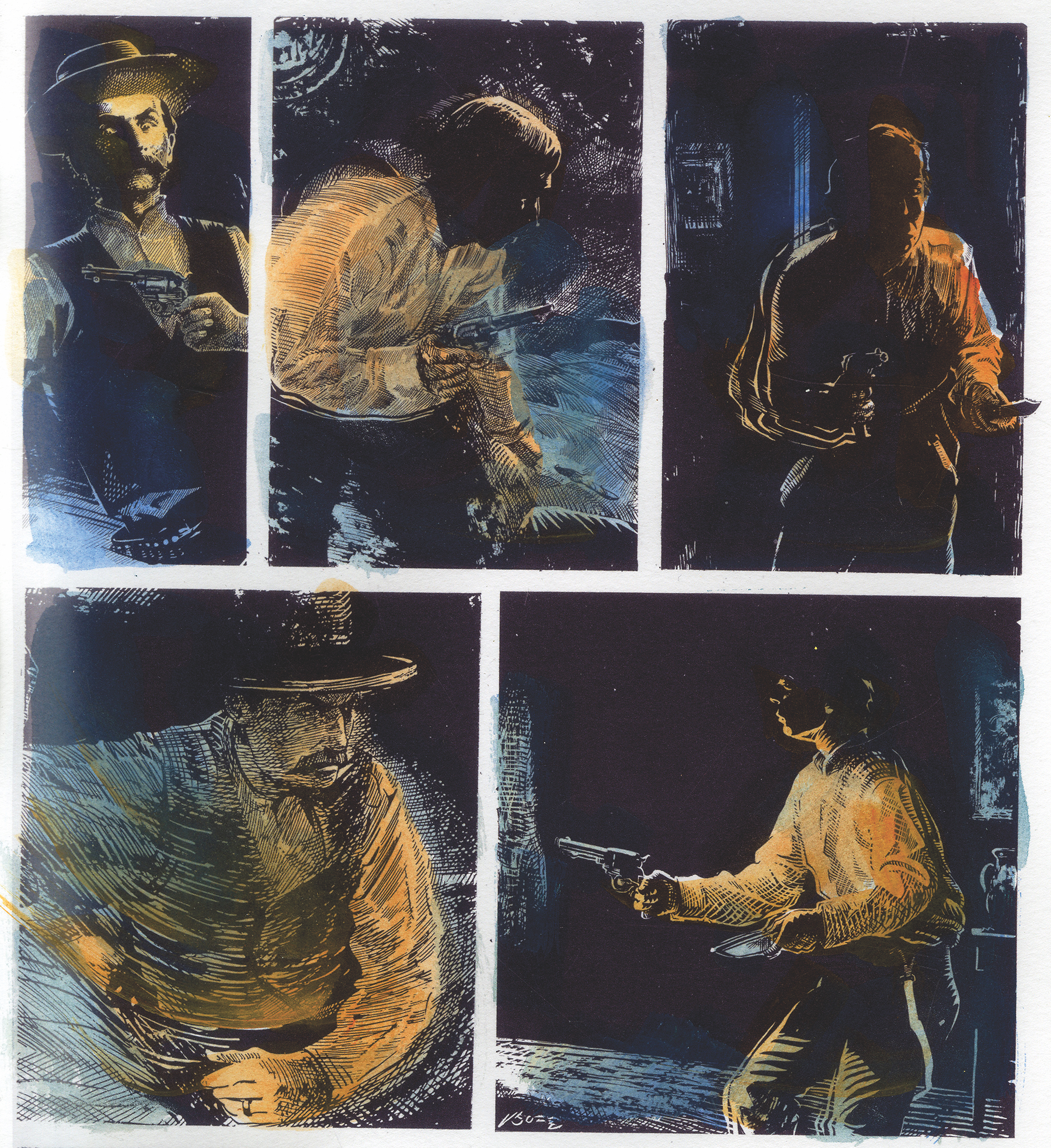

KILLING BILLY

Dead End Again

The Kid backs into Pete Maxwell’s bedroom. Garrett, engulfed in the darkness, freezes. “He came directly towards me,” Garrett recounted. “Came close to me.”

Garrett said he dared not speak because his own gun was in its holster, and he was sitting on it! “He came close to me, leaned both hands on the bed, his right hand almost touching my knee.” “The Kid must have seen, or felt, the presence of a third person at the head of the bed. He raised his pistol, a self-cocker, within a foot of my breast.” The Kid jumped back, but instead of firing, he demanded in Spanish one more time, “Quien es?” Big mistake. Garrett drew his revolver and fired twice. “The Kid fell dead. He never spoke. A struggle or two, a little strangling sound as he gasped for breath, and the Kid was with his many victims.” Thus ends the sheriff of Lincoln County’s version of the events in Pete Maxwell’s bedroom in the early hours of July 15, 1881. So, what, pray tell, is the reason for revisiting all of this for the eighteen-hundreth time when I recently claimed I had written my final word on the subject?

MOURNING BILLY

Finally, A Fitting Funeral for Billy the Kid!

We all know the Kid was put in the ground with modest fanfare. “Practically every man, woman, and child in town followed the body to the little cemetery,” remembered Paulita Maxwell. Okay, but that is still roughly only about 170 souls, certainly not the crowd Billy deserved then, or now. It has been Buckeye Blake’s dream to fix that, to make it right for the Kid with a show of proper respect and honor.

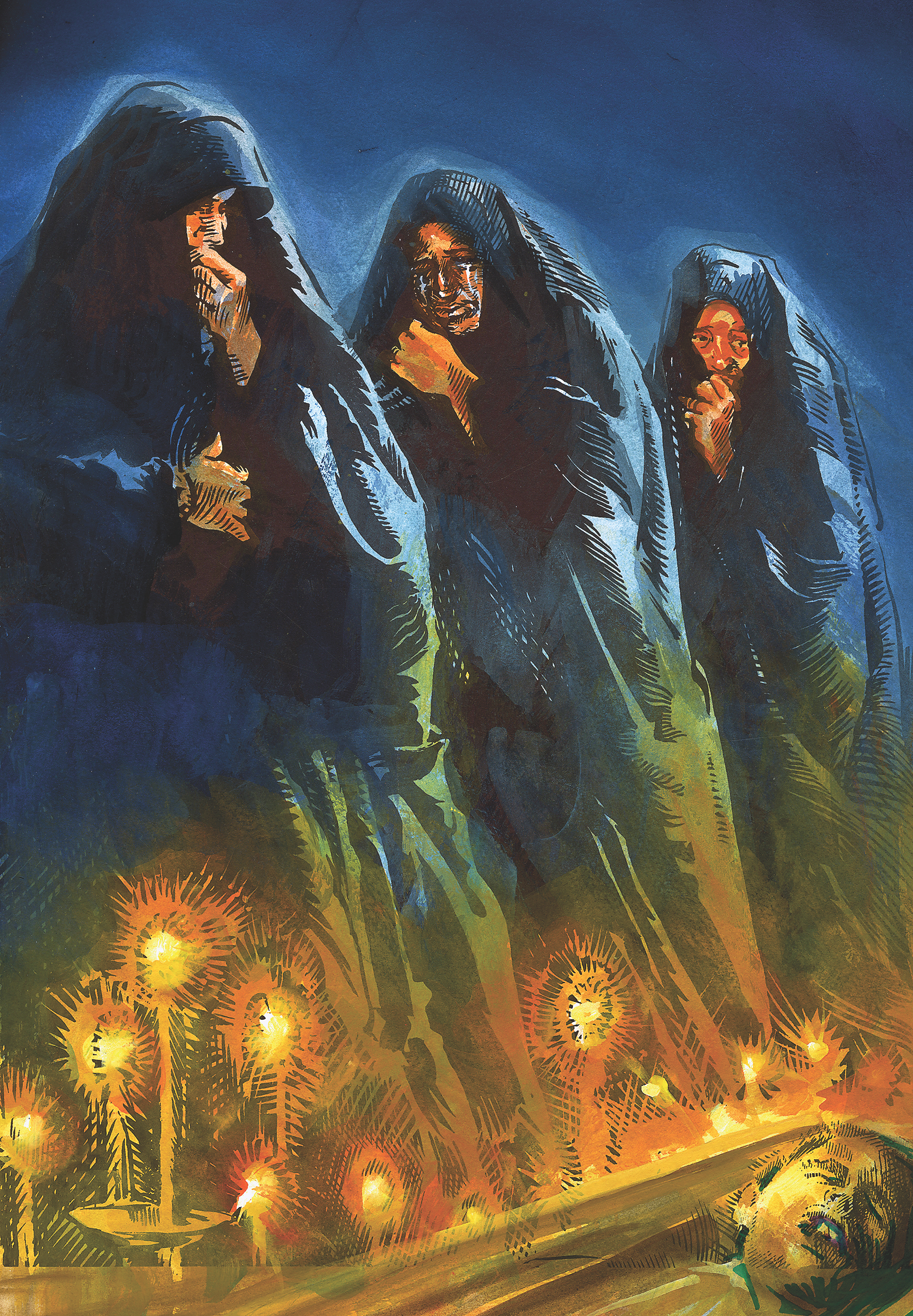

Several local Hispano women begged Garrett to allow them to remove the body, which he did. Jesus Silva and a couple others carried the Kid’s slender body to the old carpenter shop across the parade ground, near the quartermaster’s corral and placed Billy on a sturdy workbench. The fatal exit wound was plugged with a rag. (It did not bleed out until two hours after the shooting perhaps from the jostling.)A clean shirt was produced from Pete Maxwell that was too large. The women prepared the body for a wake, placing lighted candles all around his lifeless body while several Fort Sumner residents, both men and women, kept a quiet vigil over their friend’s body.

A hastily held coroner’s jury led by Alcalde Alejandro Seguro and ordered by Pat Garrett viewed the body of Billy Bonney in the carpenter’s shop to confirm the cause and manner of death.

Jesus Silva constructed the coffin and then he and Vicente Otero dug a grave in the old post cemetery.

After Billy’s body was placed in his coffin, it was moved to Beaver Smith’s saloon, where it remained until time for burial. The funeral took place in the afternoon. Garrett gave Pedro Maxwell $25 to get some proper clothing for the dead boy.

Otero used his wagon to transport the body from the saloon to the graveyard and almost everyone in the small community followed the procession.

The next day, a marker made of a stave from the picket fence he walked by the night before, was placed at the head of the grave. The marker had no last name or date, just the words, “Billy the Kid.”

And, that was the end of that.

Or, was it?

Some 20 years ago, Buckeye Blake wanted to give the Kid a proper graveside crypt, so he went to the powers that be in Fort Sumner and they flat turned him down. As he put it in an interview with Ken Amorosano back in 2014: “It didn’t go over well. They didn’t know what a crypt lid was. Thought I was part of the forensic crowd who wanted to dig up Billy. And then you’ve got the religious side—sanctity of the dead. Plus, the locals—Mexican families, especially—held the Kid in high esteem. He was their hero. They weren’t gonna let just anybody mess with him. ‘We don’t want dead people in our cemetery,’ they said. I told them, ‘Well, most of them live there already.’”

And so, Buckeye went home to Texas and destroyed his clay sculpture.

But, believe it, or not, that was then, and Buckeye’s old idea has been dusted off and approved by a new set of crypt keepers in Fort Sumner! What was dead has been resurrected. Both the outlaw and Buckeye’s project.

How The Buckeye Wake Project Finally Happened

Buckeye pitched his idea to Mary Ann Cortese and the Fort Sumner chamber. She took on the concept and championed it relentlessly. She brought in Mayor Louis Gallegos and the entire city council, who then approached Tim Roberts at the State of New Mexico about collaborating on something that would honor the Kid without opening old controversies. This led to an interpretive exhibit concept floated by Roberts who brought on Billy Roberts, Scott Smith and the late Drew Gomber. The city then pursued and won grant money to fund the project.

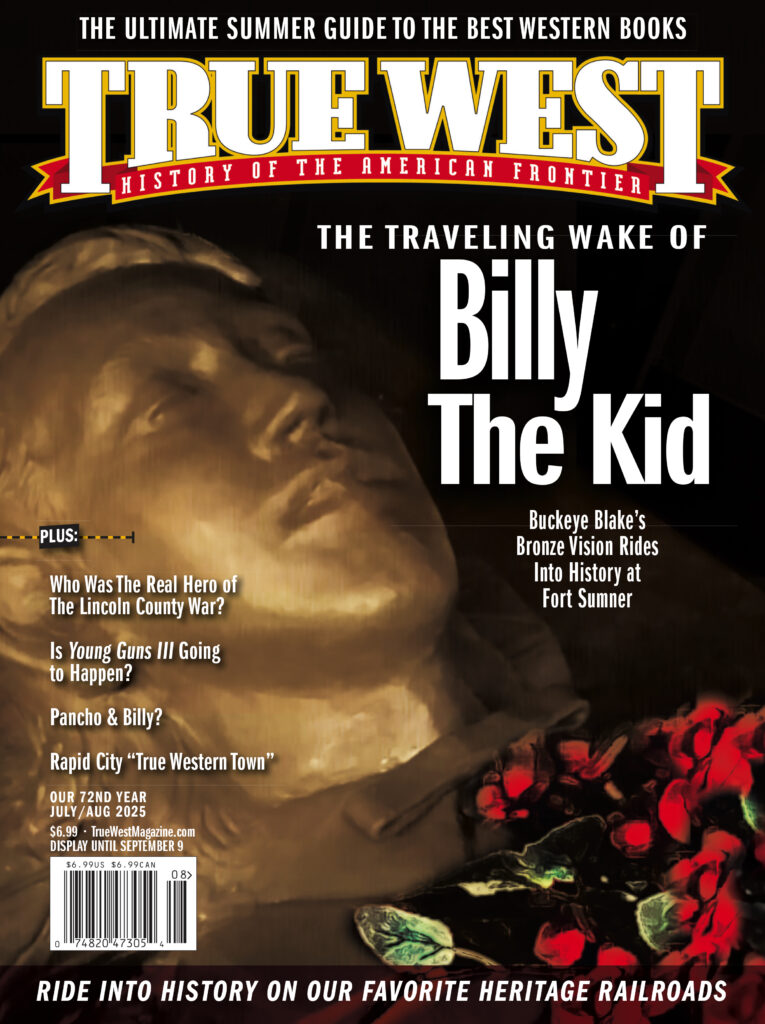

The Traveling Wake of Billy the Kid

Buckeye Blake’s wake sculpture, below, will be unveiled at the Old Fort Sumner Graveside Museum in the spring of 2026.

In the meantime you will be able to see all of this artwork, including the sculpture, on

The Traveling Wake of Billy the Kid

in the following locations (this is a tentative list and more locations may be added):

The Lamy Church, in Lamy, New Mexico, on July 4, 2025. At the Raton Museum on August 23

and at the Scottsdale Museum of the West on October 3rd.