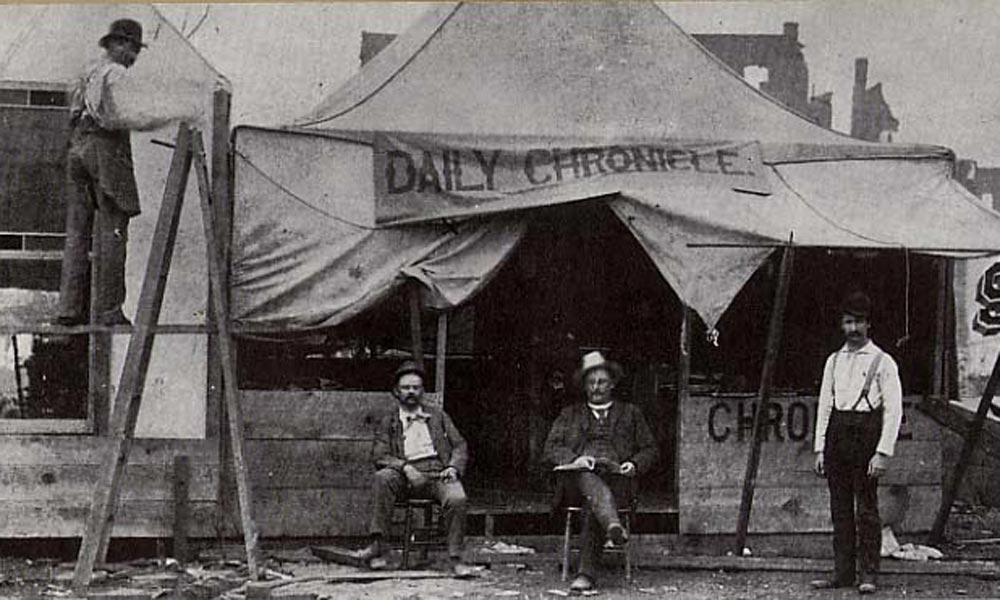

Wherever folks wandered in the rugged wilds of the West during the second half of the 19th century there remained a desire to keep up with the happenings “back in the states.” Local events such as the latest political shenanigans were always a curiosity too. Many took their politics serious to the degree that there were Republican and Democrat saloons and lo the poor stranger who might wander inside the wrong one and espouse his opinion.

There were no schools of journalism in those days as evidenced by the crude language and bad spelling found in old newspaper files. Anyone with a printing press, paper, a “shirt-tail of print” and an opinion was free to start his own newspaper. It also helped to have a dogged determination to succeed in the face of mighty tough odds.

Few editors had any kind or business background, so many found themselves in financial trouble before the ink was dry on the first issue. Early editors and publishers were usually one and the same. They were difficult to stereotype; some were torch carriers for justice; seekers of truth and champions of liberty; others were ruthless, writing with pens seemingly dipped in acid; and still others stylized their observations in a humorous, light-hearted vein. The personality of the editor, his strengths and weaknesses set the tempo and flavor of their respective chronicles. Few became wealthy and only a handful became famous.

It was critical that an editor understand the politics of their community. Lindley Branson of the Jerome Sun incurred the wrath of the powerful but secretive William Andrews Clark, owner of the United Verde Mine. When Branson tried to glean information on the wealth of the ore deposits the copper magnate leaned on the paper’s advertisers to withdraw their support. Without advertisers the paper quickly folded, forcing Branson to leave town.

The irrepressible John Clum, town mayor and editor of the Tombstone Epitaph had to call off his war with the corrupt Cochise County Ring after members of that group bought controlling interest of the paper and forced his resignation. On one occasion Clum barely escaped with his life when assassins fired on the stagecoach he was riding.

Most of these fighting editors took delight in exposing political skullduggery, especially if it was perpetrated by a faction of politicos with opposing views from the newspaper. During Tombstone’s heyday, which was highlighted between county and city politicians, J.C. Bagg, editor of the Prospector, was sentenced to 300 days in the county jail for exposing political corruption at the county level. Unfortunately for editor Bagg, one of the culprits he exposed was the judge who presided over his case.

News and events, especially of a political nature were spiced with a great deal of editorializing, much of it libelous and laced with raw vitriol. Many a newspaperman became a “one-man chamber of commerce for their respective communities and one of the most notorious was Prescott’s John Marion. The new town and territorial capital was not yet three years old when Marion became editor of the Miner. Bands of marauding Yavapai Indians preyed upon Prescottonians within sight of town. Marion’s predecessor, Emmer Bently, had been ambushed and killed in Skull Valley.

Mincing neither words nor opinions, Marion was the most vociferous of Arizona’s editors in decrying the atrocities in the territory. On January 22nd, 1870, he published a list giving dates and location of white men bushwhacked by Indians around Prescott,

Marion didn’t reserve all his vitriolic wrath for Indians and he had no equal when it came to abusive acupuncture. When Tucson took the capital away from Prescott in 1867, Marion blamed territorial governor Richard C. McCormick, accusing him of engineering the high-jacking of the capital in exchange for Pima County supporting his appointment as territorial delegate to Washington. John Wasson, editor of the McCormick-owned Tucson Arizonian took exception to Marion’s diatribe, responded in a mildly-worded editorial: the Miner has been more filthy than usual….”

Marion quickly retaliated: “So says the liar, affidavit man, scavenger, scullion and valet for McCormick and Company. We dare this abominable beggar to show where we have been filthy. But this is a way thieves and blackguards have for drawing attention from their own foul deeds and he would like to shift the odium to some decent man’s shoulders. Black dog; to your foul kennel.”

Marion also took exception to what he considered high-handed politics, on the part of “Slippery” Dick McCormick saying, “through ignorance of baseness of purpose, McCormick has, for the last two years, usurped and used power vested solely in the legislature, and, squabbling the records of various counties…..his littleness, (McCormick stood only 5’5″) who by soft soap and flunkeyism, has wormed his way into the gubernatorial chair of a territory he has helped to impoverish.”

Another editor he who felt the stinging wrath of Marion’s acrimonious pen was Judge William Berry, editor of the Yuma Sentinel.

Marion and Berry had been friends during Prescott’s early days. Although Berry was a practicing attorney, the title “judge,” was honorary. One of the judge’s character weaknesses was an over indulgence in strong drink, something Marion capitalized on in their long-standing feud. Marion questioned his right to the title of judge, although he did concede that the editor of the Sentinel was a good judge of bad whiskey.

Rivalries between territorial editors were epic, especially during Marion’s time, but few ever got the best of the fiery editor of the Prescott Miner. His verbal harangue, colorful and bombastic, sold newspapers. One of his self-describing editorial comments sums up his tumultuous life as a fighting editor: “They tried to get my scalp, both the Injuns and the white man, but damn ’em, I’m still here.”

Marion was also a hard-core Democrat come hell or high water. This was borne out during an election for county attorney, when he stubbornly supported the Democratic candidate the despite the fact the cuckold had run off with his wife.